-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anne-Marie Brady, Gobnait Byrne, Mary Brigid Quirke, Aine Lynch, Shauna Ennis, Jaspreet Bhangu, Meabh Prendergast, Barriers to effective, safe communication and workflow between nurses and non-consultant hospital doctors during out-of-hours, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 29, Issue 7, November 2017, Pages 929–934, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx133

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the nature and type of communication and workflow arrangements between nurses and doctors out-of-hours (OOH). Effective communication and workflow arrangements between nurses and doctors are essential to minimize risk in hospital settings, particularly in the out-of-hour’s period. Timely patient flow is a priority for all healthcare organizations and the quality of communication and workflow arrangements influences patient safety.

Qualitative descriptive design and data collection methods included focus groups and individual interviews

A 500 bed tertiary referral acute hospital in Ireland.

Junior and senior Non-Consultant Hospital Doctors, staff nurses and nurse managers.

Both nurses and doctors acknowledged the importance of good interdisciplinary communication and collaborative working, in sustaining effective workflow and enabling a supportive working environment and patient safety. Indeed, issues of safety and missed care OOH were found to be primarily due to difficulties of communication and workflow. Medical workflow OOH is often dependent on cues and communication to/from nursing. However, communication systems and, in particular the bleep system, considered central to the process of communication between doctors and nurses OOH, can contribute to workflow challenges and increased staff stress. It was reported as commonplace for routine work, that should be completed during normal hours, to fall into OOH when resources were most limited, further compounding risk to patient safety.

Enhancement of communication strategies between nurses and doctors has the potential to remove barriers to effective decision-making and patient flow.

Introduction

The out-of-hours (OOH) period is associated with less favourable patient health outcomes as well as unpredictable workloads and reduced support structures for clinical activity [1, 2]. Effective communication practices both within and between clinical professions are essential to minimize risk in hospital settings and improve patient care, especially during the OOH period [3, 4].

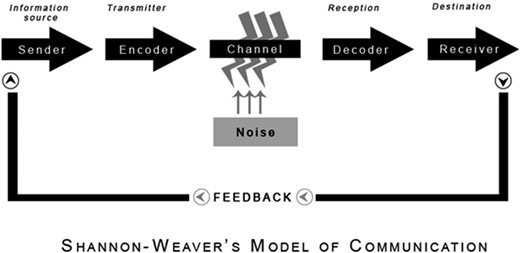

Given the complexity of modern healthcare environments it can be challenging to isolate the causative factors that inhibit workflow OOH [4]. Channels of communication are central to communication practice and enable the creation and maintenance of a continuous feedback loop essential to underpin hospital workflow. The Shannon–Weaver Linear Model of Communication [5] views communication as linear with a feedback loop (Fig. 1) and has been previously used as a framework to facilitate analysis of clinical handovers in the acute hospital setting [6], and in the safe transfer of paediatric patients [7]. It was selected as a framework for this study due to its focus on channels of and barriers to communication.

The equipment and resources used to transmit communication messages are essential to facilitate effective communication. During OOH, the bleep (or pager) systems in particular are central to communication between healthcare professionals. However, these systems have limitations [8, 9] with limited capacity to record and audit activity posing potential patient safety risks. Examples of these limitations included: (i) unanswered bleeps may be overwritten by new requests; (ii) delays in returning and responding to calls; and (iii) inability to identify and prioritize urgent calls. An examination of doctor workflow interruptions by Weigl et al. [10] highlighted that telephone calls and bleeps were the most common cause of work interruption. The broad range of doctor responsibilities in OOH contributes to the frequency of interruptions and staff availability limits the distribution of workload. A number of studies have found that such frequent interruptions can impede the quality of clinical decision-making, increase risk of error and thus reduce quality of care for patients [11–13].

Methods

Aim

To evaluate the nature and type of communication and workflow arrangements between nurses and doctors OOH.

Research design

A descriptive qualitative design [14, 15] was utilized, using focus groups with junior Non-Consultant Hospital Doctors (NCHDs) and staff nurses, and individual interviews with nurse managers, and senior NCHDs [16]. Focus groups were moderated by two researchers (PhD level), unknown to participants, with experience working in acute hospitals. Focus groups/interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed using NVIVO (Version 9). The topic guide for both interviews and focus groups included questions on participants’ experiences of OOH communication and workflow patterns. Ethical approval was granted by the authors’ affiliated university.

Setting

The hospital is a large acute tertiary referral centre, with ~500 beds and 70 000 patients attend the ED annually. In this study, the OOH period is defined as between 1700–0900 Monday–Friday and weekends. The technology used for OOH communication is known as a bleep system (one-way numeric pager) which facilitates the recipient to receive numeric messages (phone numbers of callers or emergency numbers) only.

Sample

Between December 2015 and April 2016 a total of 27 participants took part in interviews/focus groups and included NCHDs—Junior and Senior and nursing staff (Nurse Managers, Clinical Nurse Specialists and Staff Nurses). Purposive sampling was used to select participants for the individual interviews. This group included senior NCHDs (n = 3) and Nurse Managers (n = 5) All staff had experience of working during the OOH period. Length of ward experience ranged from 6 months to 20 years. Nursing staff were selected from both medical and surgical ward settings.

Analysis

Qualitative data analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s analytical Framework [17]. Credibility and trustworthiness of the findings was informed by RATS (i.e. Relevancy, Appropriateness of qualitative method, Transparency of procedures, Soundness) [18] and was further informed by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREC) [19]. Themes were assessed for inter-coder agreement between two team members and reviewed with relevant medical and surgical hospital staff, who were members of the study steering committee.

Results

Channels of communication between doctors and nurses

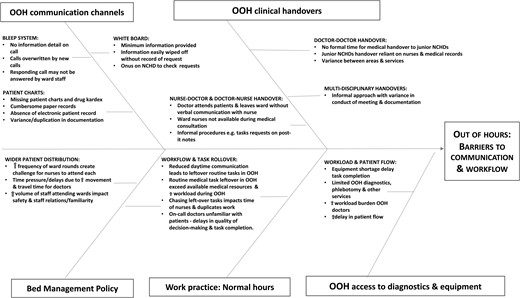

A range of contributory factors were found to inhibit communication and workflow in the findings as evident in the fishbone diagram (Fig. 2). The main channels of communication available to nurses during the OOH period were the bleep system, white board and patient charts. There was some evidence of other technologies in use (including mobile phones, email and messaging services). However, according to interviewees, the use of these were limited due to inconsistences with Wi-Fi across the hospital as well as data protection considerations. Thus, the transfer of information between nurses and junior NCHDs was particularly reliant on the bleep system. However, some dissatisfaction was expressed by both parties in this regard. The list of people on-call was inaccurate at times due to ‘people having swapped… the bleep list does not give that information’ (Nurse Manager 1). This primarily impacted on the nurses (senders of the message) and created delays at the first step in the chain of communication. Other inefficiencies with this channel of communication clearly hampered the flow of communication. Junior NCHDs were challenged by the inability to get any information on the nature of the call, limiting their opportunity to plan response or prioritize tasks/workload. One of the senior NCHD commented that the ‘bleep is a little bit unreliable’ and junior NCHDs were aware of better technology in other countries which facilitated better communication

‘I know in Australia and some hospitals they have bleeps that give you little message, so you can, you know you can prioritize the bleep before you even answer them.’ [Junior NCHD, Focus Group (FG)].

The junior NCHDS reported that many factors impacted on their abilities to answer and respond to the bleep system and they struggled with excessive volume of bleeps at certain peak periods.

‘It’s the volume, I don’t mind the sleep deprivation as much as the volume [of calls] and the feeling of being constantly bleeped’ [Junior NCHD, FG]

This was of particular importance when they were engaged in direct patient contact and could not immediately answer. Pending responses were sometimes overtaken with more recent bleeps and some junior NCHDs reported concern that earlier bleeps may be overlooked at times.

‘So it can often happen that both of us are doing procedure and neither of us can answer a bleep. And we don’t know and will never get back to it, because there is so many other bleeps coming in at the time. And you don’t know if the bleep you missed was the important bleep, you know’ [Junior NCHD, FG]

Nurses, as initiators of the communication flow, also related their frustration with unanswered bleeps and the pressure it brought about due to the inability to progress on their work and meet immediate patient need at times.

‘And you’ve another 10 patients that also need you so you’re under pressure because XXX won’t answer his bleep’ [Staff Nurse FG]

However, junior NCHDs as recipients of the beep noted that, in some cases, when they did respond to bleeps there would be no answer on the ward or the person answering the call was not aware of any request.

The second channel of communication used by nurses was the ‘to do list’ itemized on a white board in the medication preparation room. Junior NCHDs were expected to review this list when they visited wards or were attending the ward for another task. However, the majority of junior NCHDs acknowledged that this white board system presented some safety issues as they provided doctors with minimum information creating potential for mistakes. Furthermore, according to some interviewees, the white board task request may be accidentally erased and did not provide a permanent record that a request was placed.

‘And just on another point for safety and a lot of wards do have it but some wards don’t and it’s so simple, everyone writes like bed number on the white board, so it’s like 14 needs analgesia charted but we don’t know that patients name so we go to another white board to get the name, then we go to get the kardex but by the time you’ve forgotten what bed number was and you have to go back’ [Junior NCHD, FG]

‘The junior NCHD come in and they’ll just wipe them [tasks] off and not do them. But they’ll have wiped it off the board so you’re like oh the bloods were taken. And that evening you’re like oh what’s his [the patient’s] haemoglobin and you’re like oh his bloods weren’t taken’ [Staff Nurse, FG]

The final channel of communication was via the patients’ charts and included the drug kardex. Both medical and nursing staff document care on the patients’ charts in paper format. Some nurses used post-it notes, which were placed on patients’ charts to request doctors to do specific tasks. However, both NCHDs and nurses raised concerns about the continued use of paper records and included examples of issues such as missing drug charts. As junior NCHD stated ‘I know it would be totally aspirational but like electronic drug charts I think for patient safety would be so much better.’

Channels of communication between medical staff at handover

Nurses had formal handover arrangements for each shift. In contrast, the handover arrangements between OOH doctors and the doctors working regular hours were ad-hoc and informal at times. Junior medical NCHDs relied on medical records or verbal communication from nurses for their information as there were no formal handover arrangements between medical colleagues.

‘There is no handover during the weekdays… we get all of our information from the nurses on the ward by bleeps or by the white boards, every ward has a board with a list of jobs on it’ (Junior NCHD, FG)

At weekends, senior medical NCHDs attended multidisciplinary handover on Friday afternoons and received a list of patients that required a review by a senior medical NCHD. The end of OOH shift handover during the weekend constituted a handover of this list to the next Medical NCHD on-call.

‘There is an official handover because physically you have to handover the sheet of paper to the next doctor. So I don’t think it ever happens that those two registrars don’t meet, you know and I would think that they would always go through the list.’ (Senior Medical NCHD 1)

‘The surgical sign out (surgical electronic handover record) is sent usually between 7 and 7.30 AM in the morning. I record details of consults that I’d seen and stuff like that. So that the team who were taking over in the morning, I was on call for, that they’d know about them.’ (Senior NCHD 2).

This narrative illustrates how handover between the surgical senior NCHDs was more formal with the documentation of a surgical electronic handover record.

Ward rounds and chasing work after hours

Both medical and nursing staff acknowledged ‘the importance of the ward round and the communication both during and post a ward round’ (Nurse Manager 1). Changing practices in bed management influenced how patients were allocated to wards and resulted in increased numbers of consultants engaging with wards and frequency of rounds. Doctors reported irritation with the absence or limited availability of nurses (recipients of messages) attending ward rounds. Similarly, nurses noted the challenge of completing other work effectively whilst attending different ward rounds during the day. The other recipients of messages within ward rounds were junior NCHDs. The transient flow of consultants and NCHDs across the hospital to attend patients in the different wards was highlighted by nurses in contributing to delayed or incomplete communication of actions by junior NCHDS to progress the patient’s journey. Where this occurred interventions were delayed and were often only identified during OOH:

‘Or they breeze into the patient and breeze by us without saying anything, ….So in the evening you’re chasing after the doctors like you know what do you want, what’s tonight, I want this, I want that, start that, give this, give that’ [Staff Nurse FG]

The break in the chain of communication during and after ward rounds resulted in nurses spending time OOH pursuing or ‘chasing’ of work unfinished from day-time or securing follow through on actions identified earlier in the day. This led to increased tasks for on-call NCHDs.

‘The nurse needs to think ahead of what’s needed tonight, like so like it’s easy for them to come in and say put him on fluids tonight and they walk off. And they never do and then it comes to 11 o’clock that night and you’re like ah he’s meant to be on fluids, there’s none charted’ [Staff Nurse FG]

As identified by both nurses and doctors, left-over tasks from ward rounds included the rewriting of drug charts by on-call medics for unfamiliar patients, prescribing analgesia, sliding scales of insulin, warfarin, night sedation and fluids. The prescribing of pre-operative insulin regimes and patient discharge notes were also regularly allowed to roll into the OOH period. Whilst the reasons for this roll over of tasks were often valid (i.e. staff shortages, patient volume/acuity, etc.), the volume of incomplete work was not commensurate with the number of staff available to cover the OOH periods.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the barriers that impeded communication between doctors and nurses during the OOH period. It was clear from the findings that poor technology to transmit messages between healthcare professionals was a significant communication barrier during OOH. The most frequently reported method of communication between nurses and doctors was the white board and bleep system and such systems did not facilitate recording and/or auditing of their effectiveness. The present technology (bleep system) was viewed as inadequate and inefficient. There was minimum reported use of electronic communication with the exception of the surgical electronic handover record used during OOH which was developed by Ryan et al. [20]. Other technologies, such as alphanumeric paging, which facilitates the sending of messages in text via the pager were perceived by participants as more reliable than the one-way numeric paging system currently in use [8, 9]. The impact of the recession in Ireland resulted in a large decrease in health expenditure since 2009 and a lack of investment in technology such as electronic patient records within Irish hospitals [21]. The use of alternative communication tools (such as WhatsApp) [22] and short message services (SMS) [23] have been piloted in some hospitals in the UK but concerns exist about data security. In this way such methods are limited in value as any new technology needs to adhere to national and international data security regulations. The need for improved technology to facilitate communication within the health services has been recognized in this and other studies [24, 25] to help improve patient safety. Large healthcare organizations, such as the NHS UK or the HSE Ireland, should review the risks associated with using the one-way numeric paging system using the framework identified by Hibbert et al. [26]. These organizations should develop national polices to facilitate the replacement of the out-dated paging system.

The medical staff in this study reported that their patients were distributed across multiple wards, which has also been reported elsewhere [27]. This increased the length of time taken by medical staff to attend to patients as well as longer hospital ward rounds, otherwise known as ‘safari ward rounds’ [28]. These findings concerning the negative impact on efficacy have also been reported in a recent ward round audit within the hospital [29]. Nursing staff, in this study further reported that the increased frequency of ward rounds by different consultant teams disrupted the efficiency of other ward-level duties and created a barrier to the formation of cross-discipline professional relationships. Many of the requested tasks OOH were routine and resulted from decisions made during ward rounds, and not implemented, during the day-time period. Medical handover, prior to and after the OOH period was also an issue of concern. External noises to the chain of communication, such as inadequate time for medical handover at the beginning and end of the OOH period also hampered communication. The implications for inefficiency in the transmission and sharing of information was clearly evident from the volume and nature of activities ‘left-over’ from the day-time that emerged during the OOH service period. A recent systematic review identified that multidisciplinary ward rounds, which used structured communication tools, facilitated communication, collaboration and enhanced staff satisfaction [30]. An introduction of such a communication tool for ward rounds and a decrease in the ‘safari ward round’ phenomena would promote enhanced communication and collaboration and thus would potentially decrease the number of tasks requested during the OOH period. Pennell et al. [31] introduced a standardized format for the OOH multidisciplinary handover as well as the introduction of a clinical co-ordinator to monitor the functioning of the OOH team.

Limitations

The findings are confined to one hospital, however the issues identified pertaining to communication and workflow OOH do echo similar issues reported elsewhere [32, 33]. Despite the limitations, this study uncovers issues that are likely to influence workflow processes and patient safety OOH.

Implications

The chain of communication between healthcare professionals was frequently disrupted by the poor communication infrastructure such as bleeps and lack of computerized records. The lack of presence of the receiver, in this case, bedside nurses, at ward rounds also contributed to a breakdown of communication. This coupled with ‘safari ward rounds’ contributed to an excess number of tasks left for completion during the OOH period. This study has identified that some of the communication channels that would benefit from improvement (i.e. the bleep system, ward rounds and shift handovers). Some further work practice adaptation such as access to computers for both medical and nursing staff in addition to the use of ward round checklists have been reported elsewhere to be useful tools in improving ward rounds [34–36]. Increased efforts to find patient centric and flexible solutions to enable responsible use of resources and effective communication processes are likely to lead to improved working environments for staff and greater workflow efficiencies leading to improved quality of patient care.

Funding

This study was funded by the Meath Foundation Ireland.