-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kalin Werner, Mohini Kak, Christopher H Herbst, Tracy Kuo Lin, The role of community health worker-based care in post-conflict settings: a systematic review, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 38, Issue 2, March 2023, Pages 261–274, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czac072

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Countries affected by conflict often experience the deterioration of health system infrastructure and weaken service delivery. Evidence suggests that healthcare services that leverage local community dynamics may ameliorate health system-related challenges; however, little is known about implementing these interventions in contexts where formal delivery of care is hampered subsequent to conflict. We reviewed the evidence on community health worker (CHW)-delivered healthcare in conflict-affected settings and synthesized reported information on the effectiveness of interventions and characteristics of care delivery. We conducted a systematic review of studies in OVID MedLine, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL) and Google Scholar databases. Included studies (1) described a context that is post-conflict, conflict-affected or impacted by war or crisis; (2) examined the delivery of healthcare by CHWs in the community; (3) reported a specific outcome connected to CHWs or community-based healthcare; (4) were available in English, Spanish or French and (5) were published between 1 January 2000 and 6 May 2021. We identified 1976 articles, of which 55 met the inclusion criteria. Nineteen countries were represented, and five categories of disease were assessed. Evidence suggests that CHW interventions not only may be effective but also efficient in circumventing the barriers associated with access to care in conflict-affected areas. CHWs may leverage their physical proximity and social connection to the community they serve to improve care by facilitating access to care, strengthening disease detection and improving adherence to care. Specifically, case management (e.g. integrated community case management) was documented to be effective in improving a wide range of health outcomes and should be considered as a strategy to reduce barrier to access in hard-to-reach areas. Furthermore, task-sharing strategies have been emphasized as a common mechanism for incorporating CHWs into health systems.

This review characterizes the impact of community health worker (CHW)-delivered healthcare in fragile and conflict-affected settings presented in published studies.

Evidence points to the value of leveraging CHWs to deliver healthcare and serve the unique health needs of populations residing in conflict-affected settings.

Community-based care addresses key barriers in four critical ways: (1) increasing access to essential healthcare services, (2) improving case management and treatment adherence, (3) enhancing disease detection and monitoring and (4) facilitating the scaling up of services.

Key enablers for community-based care include training and support provided to CHWs and material resources provided to CHWs.

Introduction

The prevalence of armed conflict and violence globally has resulted in over 484 million people—including some of the world’s most vulnerable populations—currently living in fragile or conflict-affected states (Gleditsch et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2017; The World Bank, 2018; Institute for Economics & Peace, 2021). By 2030, it is expected that 46% of the global poor will reside in areas characterized as either fragile or conflict-affected (The World Bank, 2019). Although battle-related deaths have declined since 1946, conflict is estimated to constitute 80% of all humanitarian needs (The World Bank, 2019).

Over recent decades, a rise in protracted and recurring conflict, with frequent relapses into violence, reveals a lack of clarity for determining when states are in a period of active conflict or immediately after conflict. There is little consensus in the literature regarding the use of the term ‘post-conflict’. Fundamentally, the post-conflict period exists at a time between a conflict and peace. On the one hand, some studies identify this period as a transitional state, ‘most crucial in supporting or underpinning still fragile cease-fires or peace processes by helping to create conditions for political stability, security, justice and social equity’ (UNDG/ECHA Working Group on Transition, 2004). On the other hand, development partners and international agencies identify this period by its characteristics rather than by time. Here, post-conflict settings are identified by their ‘low levels of capability to implement core responsibilities’ (Woolcock, 2014), or ‘fundamental failure of the state to perform functions necessary to meet citizens’ basic needs and expectations’ (Department for International Development, 2005). The World Bank, well known for its annual country classifications, associates ‘high levels of institutional and social fragility’ with those categorized as fragile and conflict-affected situations.

Regardless of varying characterizations, it is clear that countries that have suffered from recent conflict, or that are now suffering from conflict, often experience a deterioration of their health system infrastructure and a weakening of service delivery. As such, populations residing in fragile, conflict-affected and post-conflict states (FCAPCS) face mass displacement and exposure to atrocities of violence, which directly increases vulnerability to communicable diseases and the prevalence of psychological disorders (Rutherford and Saleh, 2019). Disintegrated health infrastructure makes responding to the health needs of these populations even more challenging. Damaged infrastructure, limited human resources and fragmented service delivery result in substantial increases in morbidity and mortality from non-violent causes. All the while, individuals who have experienced conflict exhibit some of the worst indicators of maternal and infant mortality and need a tremendous amount of care. The populations residing in FCAPCS face enormous barriers in achieving global targets for their health systems. For example, only one in five fragile and conflict-affected states are on track to achieve the sustainable development goals (Samman et al., 2018).

There is growing interest in addressing these obstacles and testing solutions to reach difficult-to-access areas in FCAPCS using low-cost, scalable solutions to offset the burden of damaged facilities, broken supply chains and weakened health workforces. Healthcare services that leverage local community dynamics pose a potential solution in contexts where formal delivery of care is hampered by conflict. Central to such services are community health workers (CHWs) or lay individuals who not only have an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language but who also serve as an effective option to address the dwindling health workforce that resulted from conflict-induced attrition (Olaniran et al., 2017). CHWs are expected to undertake a number of functions such as performing health assessments, delivering remote primary care, monitoring patients for follow-up and providing targeted health education. Often this involves personalized care through case management and care coordination. CHWs also play non-therapeutic roles, providing social support, helping patients to access local services and supporting patients understand medical advice and recommendations (Hartzler et al., 2018). CHWs are effective in improving population health across diverse settings (Perry and Zulliger, 2012; Perry et al., 2014), have a positive impact on health development goals (Bhutta et al., 2010) and are cost-effective (Vaughan et al., 2015). Prior systematic reviews have further identified the value of CHWs for specific conditions, such as maternal and child health (Gilmore and Mcauliffe, 2013) or infectious disease. A growing body of literature has determined the requirements for the sustainability and scale up of CHWs in low-income settings (Pallas et al., 2013). However, not enough is known about the delivery and success of CHW-based interventions in relation to the specific contextual challenges faced by post-conflict settings.

Strategies to deliver care outside a hospital or clinic may be a particularly relevant approach where disease burdens are high, but infrastructure is weakened. CHW programmes may play a critical role in linking relief, rehabilitation and development approaches, which aim to link short-term measures to longer-term development programmes for a more sustainable response to health systems under stress (Nicholls et al., 2015; Affun-Adegbulu et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2020). However, healthcare delivery strategies that are insensitive to the fragile and conflict-affected settings risk aggravating existing disparities even further. Thus, it is critical for policymakers to understand which types of policies should be adopted in conjunction with CHW deployment to best meet the healthcare needs of the population in FCAPCS. The aim of this study is to characterize systematically the literature on the role of CHW-delivered healthcare in fragile and conflict-affected settings and synthesize reported information on the effect of these interventions on key healthcare functions.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was performed following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA) guidelines to identify articles relevant to the study topic (Liberati et al., 2009). OVID MedLine, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL) and Google Scholar databases were searched in May 2021. The search strategy used context-specific keywords—‘post conflict’, ‘post war’ and ‘fragile state’—in combination with topic-related keywords associated with CHWs and community-based healthcare (CBHC) services. The full search strategy, which combines relevant keywords using Boolean operators, can be found in Supplementary 1.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they (1) described a context that is post-conflict, conflict-affected or was impacted by war or crisis; (2) examined the delivery of healthcare by CHWs in the community; (3) reported a specific outcome connected to CHWs or CBHC; (4) were available in English, Spanish, or French and (5) were published between 1 January 2000 and 6 May 2021. We restricted our review to the most recent two decades to capture data best equipped to inform contemporary decision-making. Details of both inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion . | Exclusion . |

|---|---|

|

|

| Inclusion . | Exclusion . |

|---|---|

|

|

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion . | Exclusion . |

|---|---|

|

|

| Inclusion . | Exclusion . |

|---|---|

|

|

Key definitions used in this review

| Term . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| CHWs | Paraprofessionals or lay individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language have received standardized job-related training of a shorter duration than health professionals; their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community (Olaniran et al., 2017) |

| CBHC | All services provided by people who spend a substantial part of their working time outside a health facility, discharging their services at the individual, family or community level as well as primary healthcare services provided in small local health facilities (World Health Organization, 2016) |

| Post-conflict | A transitional period, characterized by destabilization, where past war or conflict exists on one end and a future period of peace on the other, often most associated with a period of rebuilding and reconstruction |

| Term . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| CHWs | Paraprofessionals or lay individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language have received standardized job-related training of a shorter duration than health professionals; their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community (Olaniran et al., 2017) |

| CBHC | All services provided by people who spend a substantial part of their working time outside a health facility, discharging their services at the individual, family or community level as well as primary healthcare services provided in small local health facilities (World Health Organization, 2016) |

| Post-conflict | A transitional period, characterized by destabilization, where past war or conflict exists on one end and a future period of peace on the other, often most associated with a period of rebuilding and reconstruction |

| Term . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| CHWs | Paraprofessionals or lay individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language have received standardized job-related training of a shorter duration than health professionals; their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community (Olaniran et al., 2017) |

| CBHC | All services provided by people who spend a substantial part of their working time outside a health facility, discharging their services at the individual, family or community level as well as primary healthcare services provided in small local health facilities (World Health Organization, 2016) |

| Post-conflict | A transitional period, characterized by destabilization, where past war or conflict exists on one end and a future period of peace on the other, often most associated with a period of rebuilding and reconstruction |

| Term . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| CHWs | Paraprofessionals or lay individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language have received standardized job-related training of a shorter duration than health professionals; their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community (Olaniran et al., 2017) |

| CBHC | All services provided by people who spend a substantial part of their working time outside a health facility, discharging their services at the individual, family or community level as well as primary healthcare services provided in small local health facilities (World Health Organization, 2016) |

| Post-conflict | A transitional period, characterized by destabilization, where past war or conflict exists on one end and a future period of peace on the other, often most associated with a period of rebuilding and reconstruction |

Only study designs reporting a specific outcome related to healthcare were included. Studies without empirical data, conference abstracts, posters or protocols were excluded from the review. We followed close definitions of key terms in determining eligibility of studies (Box 1). For example, a study was excluded from the review if the study author(s) did not explicitly include details of conflict, crisis or war as a feature of the context of the study; such studies were excluded even when the reviewers were aware that conflict had existed in the area. Likewise, CHWs were defined as a cadre of healthcare providers who are (1) from the community they serve and (2) without formal training (Lehmann and Sanders, 2007). For example, midwives have become an increasingly professionalized cadre in recent years, and they often receive formal training (Castro Lopes et al., 2016). Therefore, they were considered to be formal healthcare workers for this review, and articles that discussed delivery of care by midwives were excluded. Similarly, care strategies that focused on the delivery of services within a clinical setting, regardless of size or remoteness, were not considered ‘community-based’ and were excluded from this review.

Duplicate studies were eliminated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (Microsoft Corp, 2019). Following PRISMA guidelines, two reviewers independently assessed studies for eligibility first by title and abstract, removing those that did not meet the criteria (Liberati et al., 2009). Full texts of the remaining articles were then retrieved and screened again using the inclusion criteria. Reviewers checked all within-publication references to identify additional sources. As a desk-based review, no ethical approval was sought.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were drawn from included full-text articles and compiled using a predefined 13-item extraction sheet. Reviewers then used the matrix to summarize descriptively the results in tables by country of origin, study design, condition or disease addressed, type of intervention and effect size or impact of the intervention. Descriptive analysis of key characteristics of included publications was conducted, and consensus on themes related to the key functions of CHWs was reached by dialogue between the two reviewers.

Results

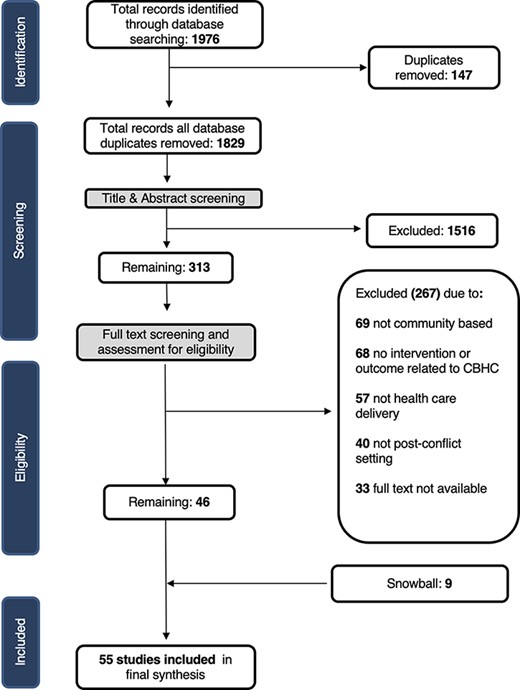

A total of 1976 studies were identified in our search (Figure 1); 147 duplicates were removed. Based on title and abstract review, 1516 studies were excluded. Full-text screening for eligibility was conducted on 313 articles: 68 studies did not assess community-based intervention or CHWs and were removed, 57 were not related to the delivery of healthcare, 49 did not report a specific outcome connected to CHW or CBHC and 40 were not conducted in post-conflict settings. Of the 313 articles, 33 studies either had no full text available or were available only as an abstract or protocol, and 15 of the 313 studies were systematic reviews with no empirical outcome. Although these studies were not included in our review, their reference lists were searched. Snowball methods were used to search reference lists for all studies included after full-text review, adding nine papers. The process resulted in 55 full-text articles included in our final review.

Study characteristics

The final synthesis included representation from 19 countries across four regions. Liberia was the most frequently reported country (n = 11), followed by Afghanistan (n = 10) and then Uganda (n = 8). Over half of all the studies (n = 35) reported were derived from the sub-Saharan African region, with the remainder from the South Asian region (n = 17), the East Asian Pacific Region (n = 5) and the Middle East North African region (n = 4). Of 55 studies, 11 were conducted in rural settings and 2 in urban settings (Weiss et al., 2015). Three articles focused specifically on displaced persons, refugee camps or humanitarian settings (Bolton et al., 2007; Shanks et al., 2013; Naal et al., 2021).

The majority of the articles used an observational study design (n = 30). These included cross-sectional studies (n = 19) (Edward et al., 2007; Hadi et al., 2007; Ahmadzai et al., 2008; Teela et al., 2009; Huber et al., 2010; Mullany et al., 2010; Viswanathan et al., 2012; Shanks et al., 2013; Mayhew et al., 2014; Nanyonjo, 2014; Luckow et al., 2017; Ratnayake et al., 2017; Ruckstuhl et al., 2017; Soe et al., 2017; Edmond et al., 2018; Kohrt et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2018; Kasang et al., 2019; Dal Santo et al., 2020), case studies (n = 6) (Marsh et al., 2012; Giugliani et al., 2014; Newbrander et al., 2014; Ventevogel, 2016; Brault et al., 2018; Healey et al., 2021), longitudinal studies (n = 3) (Smith et al., 2014a,b; Oo, 2018) and cohort studies (n = 2) (Hawkes et al., 2009; Wickett et al., 2018). Of the final 55 studies, 12 studies were controlled trials (Bass et al., 2012; Dawson et al., 2018; Mutamba et al., 2018; White et al., 2018; Schneider et al., 2020), including 7 randomized control trials (Bolton et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2015; Bass et al., 2016; Rahman et al., 2016; 2019a,b; Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2020). Six of the studies were qualitative studies utilizing survey methodologies, focus groups or interviews (Bass et al., 2013; Abramowitz et al., 2015; Fiekert, 2002; Musinguzi et al., 2017; Zou et al., 2020; Naal et al., 2021). Six studies used mixed methods(Palmer et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2017; Ojanduru et al., 2018; Mai et al., 2019; Van Boetzelaer et al., 2019; Ferdinand et al., 2020) and one used a simulation model (Stijntjes, 2015). Additional details are shown in Table 2 (See Annexe).

Key characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) . | Country origin of data . | Methods/study design . | Disease area . | Intervention . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Liberia | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | Community-based triage training |

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Iraq | RCT | Mental health | Psychoeducation |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Problem-solving counselling |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Qualitative study | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Malnutrition | Treatment protocol and screening for malnutrition |

| Bolton et al. (2007) | Uganda | RCT | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Brault et al. (2018) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | Outreach campaigns, CHWs and trained traditional midwives |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Computer tablet-based health video library with counselling |

| Dawson et al. (2018) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive behaviour therapy |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Edward et al. (2007) | Mozambique | Observational | Childhood illness | CHW household visits |

| Ferdinand et al. (2020) | Central African Republic | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Case management |

| Fiekert (2002) | Afghanistan | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Giugliani et al. (2014) | Angola | Case study | Maternal and child health | Placing CHWs in the community |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Rapid diagnostic testing |

| Healey et al. (2021) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Huber et al. (2010) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Case identification |

| Khan et al. (2017) | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Mental health | At-home psycho-educational sessions |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Uganda, Liberia and Nepal | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Training and supervision programme for CHWs |

| Luckow et al. (2017) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Mai et al. (2019) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based family planning |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | Sierra Leone | Case study | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Malnutrition | Community-based growth monitoring sessions |

| Mullany et al. (2010) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | Uganda | Qualitative study | Primary health care | Village health teams |

| Mutamba et al. (2018) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Training for village caregivers |

| Naal et al. (2021) | Lebanon | Qualitative study | Reproductive health | Female CHWs |

| Nakimuli-Mpungu et al. (2020) | Uganda | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group support psychotherapy |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | Uganda | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Newbrander et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Case study | Maternal and child health | Basic package of health services |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Uganda | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based group learning and counselling |

| Oo (2018) | Afghanistan | Longitudinal study | Maternal and child health | iCCM |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Screening and referrals |

| Rahman et al. (2016) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Weekly individual sessions on problem solving, behavioural activation and stress management |

| Rahman et al. (2019b) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group sessions on behavioural strategies |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision |

| Ratnayake et al. (2017) | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community-based adherence support |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | Central African Republic | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | At-home case management |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Narrative exposure therapy delivered by lay counsellors |

| Shanks et al. (2013) | CAR, Colombia, DRC, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Russia | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Routine mental health programme with individual counselling |

| Smith et al. (2014a) | Liberia | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Providing education and misoprostol to pregnant women |

| Smith et al. (2014b) | South Sudan | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Distribution of misoprostol during home visits |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Myanmar | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community mobilization and awareness raising |

| Stijntjes (2015) | Liberia | Simulation model | Infectious diseases | Disease surveillance |

| Teela et al. (2009) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Lay maternal health workers placed in the community |

| Ventevogel (2016) | Burundi | Case study | Mental health | Psychosocial volunteers |

| Viswanathan et al. (2012) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Contraceptives |

| Weiss et al. (2015) [19] | Iraq | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive processing therapy |

| White et al. (2018) [54] | Liberia | Controlled trial | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Wickett et al. (2018) [50] | Liberia | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Food support, reimbursement of transport and social assistance |

| Zou et al. (2020) [64] | Sierra Leone | Qualitative study | Chronic diseases | Hypertensive and diabetic case management |

| Author (year) . | Country origin of data . | Methods/study design . | Disease area . | Intervention . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Liberia | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | Community-based triage training |

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Iraq | RCT | Mental health | Psychoeducation |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Problem-solving counselling |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Qualitative study | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Malnutrition | Treatment protocol and screening for malnutrition |

| Bolton et al. (2007) | Uganda | RCT | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Brault et al. (2018) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | Outreach campaigns, CHWs and trained traditional midwives |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Computer tablet-based health video library with counselling |

| Dawson et al. (2018) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive behaviour therapy |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Edward et al. (2007) | Mozambique | Observational | Childhood illness | CHW household visits |

| Ferdinand et al. (2020) | Central African Republic | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Case management |

| Fiekert (2002) | Afghanistan | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Giugliani et al. (2014) | Angola | Case study | Maternal and child health | Placing CHWs in the community |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Rapid diagnostic testing |

| Healey et al. (2021) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Huber et al. (2010) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Case identification |

| Khan et al. (2017) | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Mental health | At-home psycho-educational sessions |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Uganda, Liberia and Nepal | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Training and supervision programme for CHWs |

| Luckow et al. (2017) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Mai et al. (2019) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based family planning |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | Sierra Leone | Case study | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Malnutrition | Community-based growth monitoring sessions |

| Mullany et al. (2010) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | Uganda | Qualitative study | Primary health care | Village health teams |

| Mutamba et al. (2018) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Training for village caregivers |

| Naal et al. (2021) | Lebanon | Qualitative study | Reproductive health | Female CHWs |

| Nakimuli-Mpungu et al. (2020) | Uganda | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group support psychotherapy |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | Uganda | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Newbrander et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Case study | Maternal and child health | Basic package of health services |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Uganda | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based group learning and counselling |

| Oo (2018) | Afghanistan | Longitudinal study | Maternal and child health | iCCM |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Screening and referrals |

| Rahman et al. (2016) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Weekly individual sessions on problem solving, behavioural activation and stress management |

| Rahman et al. (2019b) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group sessions on behavioural strategies |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision |

| Ratnayake et al. (2017) | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community-based adherence support |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | Central African Republic | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | At-home case management |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Narrative exposure therapy delivered by lay counsellors |

| Shanks et al. (2013) | CAR, Colombia, DRC, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Russia | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Routine mental health programme with individual counselling |

| Smith et al. (2014a) | Liberia | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Providing education and misoprostol to pregnant women |

| Smith et al. (2014b) | South Sudan | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Distribution of misoprostol during home visits |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Myanmar | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community mobilization and awareness raising |

| Stijntjes (2015) | Liberia | Simulation model | Infectious diseases | Disease surveillance |

| Teela et al. (2009) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Lay maternal health workers placed in the community |

| Ventevogel (2016) | Burundi | Case study | Mental health | Psychosocial volunteers |

| Viswanathan et al. (2012) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Contraceptives |

| Weiss et al. (2015) [19] | Iraq | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive processing therapy |

| White et al. (2018) [54] | Liberia | Controlled trial | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Wickett et al. (2018) [50] | Liberia | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Food support, reimbursement of transport and social assistance |

| Zou et al. (2020) [64] | Sierra Leone | Qualitative study | Chronic diseases | Hypertensive and diabetic case management |

DOTS = directly observed treatment strategy.

Key characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) . | Country origin of data . | Methods/study design . | Disease area . | Intervention . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Liberia | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | Community-based triage training |

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Iraq | RCT | Mental health | Psychoeducation |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Problem-solving counselling |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Qualitative study | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Malnutrition | Treatment protocol and screening for malnutrition |

| Bolton et al. (2007) | Uganda | RCT | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Brault et al. (2018) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | Outreach campaigns, CHWs and trained traditional midwives |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Computer tablet-based health video library with counselling |

| Dawson et al. (2018) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive behaviour therapy |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Edward et al. (2007) | Mozambique | Observational | Childhood illness | CHW household visits |

| Ferdinand et al. (2020) | Central African Republic | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Case management |

| Fiekert (2002) | Afghanistan | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Giugliani et al. (2014) | Angola | Case study | Maternal and child health | Placing CHWs in the community |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Rapid diagnostic testing |

| Healey et al. (2021) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Huber et al. (2010) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Case identification |

| Khan et al. (2017) | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Mental health | At-home psycho-educational sessions |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Uganda, Liberia and Nepal | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Training and supervision programme for CHWs |

| Luckow et al. (2017) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Mai et al. (2019) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based family planning |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | Sierra Leone | Case study | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Malnutrition | Community-based growth monitoring sessions |

| Mullany et al. (2010) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | Uganda | Qualitative study | Primary health care | Village health teams |

| Mutamba et al. (2018) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Training for village caregivers |

| Naal et al. (2021) | Lebanon | Qualitative study | Reproductive health | Female CHWs |

| Nakimuli-Mpungu et al. (2020) | Uganda | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group support psychotherapy |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | Uganda | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Newbrander et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Case study | Maternal and child health | Basic package of health services |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Uganda | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based group learning and counselling |

| Oo (2018) | Afghanistan | Longitudinal study | Maternal and child health | iCCM |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Screening and referrals |

| Rahman et al. (2016) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Weekly individual sessions on problem solving, behavioural activation and stress management |

| Rahman et al. (2019b) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group sessions on behavioural strategies |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision |

| Ratnayake et al. (2017) | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community-based adherence support |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | Central African Republic | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | At-home case management |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Narrative exposure therapy delivered by lay counsellors |

| Shanks et al. (2013) | CAR, Colombia, DRC, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Russia | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Routine mental health programme with individual counselling |

| Smith et al. (2014a) | Liberia | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Providing education and misoprostol to pregnant women |

| Smith et al. (2014b) | South Sudan | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Distribution of misoprostol during home visits |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Myanmar | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community mobilization and awareness raising |

| Stijntjes (2015) | Liberia | Simulation model | Infectious diseases | Disease surveillance |

| Teela et al. (2009) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Lay maternal health workers placed in the community |

| Ventevogel (2016) | Burundi | Case study | Mental health | Psychosocial volunteers |

| Viswanathan et al. (2012) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Contraceptives |

| Weiss et al. (2015) [19] | Iraq | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive processing therapy |

| White et al. (2018) [54] | Liberia | Controlled trial | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Wickett et al. (2018) [50] | Liberia | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Food support, reimbursement of transport and social assistance |

| Zou et al. (2020) [64] | Sierra Leone | Qualitative study | Chronic diseases | Hypertensive and diabetic case management |

| Author (year) . | Country origin of data . | Methods/study design . | Disease area . | Intervention . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Liberia | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | Community-based triage training |

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Iraq | RCT | Mental health | Psychoeducation |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Problem-solving counselling |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Qualitative study | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Malnutrition | Treatment protocol and screening for malnutrition |

| Bolton et al. (2007) | Uganda | RCT | Mental health | Psychotherapy |

| Brault et al. (2018) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | Outreach campaigns, CHWs and trained traditional midwives |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Computer tablet-based health video library with counselling |

| Dawson et al. (2018) | Indonesia | Controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive behaviour therapy |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Edward et al. (2007) | Mozambique | Observational | Childhood illness | CHW household visits |

| Ferdinand et al. (2020) | Central African Republic | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Case management |

| Fiekert (2002) | Afghanistan | Qualitative study | Infectious diseases | DOTS |

| Giugliani et al. (2014) | Angola | Case study | Maternal and child health | Placing CHWs in the community |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Rapid diagnostic testing |

| Healey et al. (2021) | Liberia | Case study | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Huber et al. (2010) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Case identification |

| Khan et al. (2017) | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Mental health | At-home psycho-educational sessions |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Uganda, Liberia and Nepal | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Training and supervision programme for CHWs |

| Luckow et al. (2017) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Maternal and child health | CHW household visits |

| Mai et al. (2019) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based family planning |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | Sierra Leone | Case study | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Malnutrition | Community-based growth monitoring sessions |

| Mullany et al. (2010) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | CHW household visits |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | Uganda | Qualitative study | Primary health care | Village health teams |

| Mutamba et al. (2018) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Training for village caregivers |

| Naal et al. (2021) | Lebanon | Qualitative study | Reproductive health | Female CHWs |

| Nakimuli-Mpungu et al. (2020) | Uganda | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group support psychotherapy |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | Uganda | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Newbrander et al. (2014) | Afghanistan | Case study | Maternal and child health | Basic package of health services |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Uganda | Mixed methods | Reproductive health | Community-based group learning and counselling |

| Oo (2018) | Afghanistan | Longitudinal study | Maternal and child health | iCCM |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | South Sudan | Mixed methods | Infectious diseases | Screening and referrals |

| Rahman et al. (2016) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Weekly individual sessions on problem solving, behavioural activation and stress management |

| Rahman et al. (2019b) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Group sessions on behavioural strategies |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision |

| Ratnayake et al. (2017) | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Liberia | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community-based adherence support |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | Central African Republic | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | At-home case management |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Uganda | Controlled trial | Mental health | Narrative exposure therapy delivered by lay counsellors |

| Shanks et al. (2013) | CAR, Colombia, DRC, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Russia | Cross-sectional | Mental health | Routine mental health programme with individual counselling |

| Smith et al. (2014a) | Liberia | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Providing education and misoprostol to pregnant women |

| Smith et al. (2014b) | South Sudan | Longitudinal study | Reproductive health | Distribution of misoprostol during home visits |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Myanmar | Cross-sectional | Infectious diseases | Community mobilization and awareness raising |

| Stijntjes (2015) | Liberia | Simulation model | Infectious diseases | Disease surveillance |

| Teela et al. (2009) | Burma (Myanmar) | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Lay maternal health workers placed in the community |

| Ventevogel (2016) | Burundi | Case study | Mental health | Psychosocial volunteers |

| Viswanathan et al. (2012) | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Reproductive health | Contraceptives |

| Weiss et al. (2015) [19] | Iraq | Randomized controlled trial | Mental health | Cognitive processing therapy |

| White et al. (2018) [54] | Liberia | Controlled trial | Childhood illness | iCCM |

| Wickett et al. (2018) [50] | Liberia | Cohort study | Infectious diseases | Food support, reimbursement of transport and social assistance |

| Zou et al. (2020) [64] | Sierra Leone | Qualitative study | Chronic diseases | Hypertensive and diabetic case management |

DOTS = directly observed treatment strategy.

Interventions described in the articles addressed several disease areas. The most frequently reported disease area was mental health and psychosocial well-being (n = 16) (Bolton et al., 2007; Bass et al., 2012; 2013; 2016; Shanks et al., 2013; Weiss et al., 2015; Ventevogel, 2016; Khan et al., 2017; Dawson et al., 2018; Kohrt et al., 2018; Mutamba et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2019a,b; Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2020; Schneider et al., 2020; Bowsher et al., 2021) followed by maternal and reproductive health (n = 12) (Hadi et al., 2007; Teela et al., 2009; Huber et al., 2010; Mullany et al., 2010; Viswanathan et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014a,b; Edmond et al., 2018; Ojanduru et al., 2018; Mai et al., 2019; Dal Santo et al., 2020; Naal et al., 2021), infectious diseases (n = 12) (Ahmadzai et al., 2008; Hawkes et al., 2009; Palmer et al., 2014; Abramowitz et al., 2015; Fiekert, 2002; Stijntjes, 2015; Ruckstuhl et al., 2017; Soe et al., 2017; Rogers et al., 2018; Wickett et al., 2018; Kasang et al., 2019; Ferdinand et al., 2020) and childhood illnesses (n = 11) (Edward et al., 2007; Marsh et al., 2012; Giugliani et al., 2014; Nanyonjo, 2014; Newbrander et al., 2014; Luckow et al., 2017; Ratnayake et al., 2017; Brault et al., 2018; Oo, 2018; White et al., 2018; Healey et al., 2021).

Group psychosocial strategies were the most commonly reported intervention for mental health and psychosocial well-being (n = 6) and evaluated amongst diverse populations. Five studies evaluated continuity of mental healthcare through various means, including the provision of routine mental health services across nine humanitarian settings (Shanks et al., 2013); home-based psychosocial educational sessions (Khan et al., 2017); integrating psychiatric care into general healthcare services (Ventevogel, 2016) and the use of non-specialist mental health provision in primary care settings (Kohrt et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2019b) (Rahman et al., 2016). Our review included additional interventions such as treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders (Bass et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2020), behavioural psychotherapy counselling approaches (Weiss et al., 2015) and the use of technology-assisted trainings to scale up trained CHWs (Rahman et al., 2019a).

Six studies investigated maternal and reproductive health strategies covering antenatal and post-natal care interventions (Edmond et al., 2018), which aimed to increase reproductive services awareness (Hadi et al., 2007), emergency obstetrics care (Mullany et al., 2010), contraceptive use (Huber et al., 2010; Mai et al., 2019) and family planning (Ojanduru et al., 2018). Other interventions identified in our review included advanced distribution of misoprostol (Smith et al., 2014a; 2014b); the use of health video libraries for community counselling (Dal Santo et al., 2020); a combined programme of modern contraceptive use, antenatal care and skilled birthing attendance (Viswanathan et al., 2012) and a mobile obstetric maternal health programme (Teela et al., 2009; Mullany et al., 2010).

Many of the childhood illness studies evaluated integrated community case management (iCCM) strategies (Marsh et al., 2012; Nanyonjo, 2014; Ratnayake et al., 2017; White et al., 2018). Nearly all studies found large substantive improvements—as indicated by statistical analysis—in treatment by qualified providers and decreased under-five mortality; although, two of the studies found no significant changes for diarrhoea treatment (Nanyonjo, 2014; Ratnayake et al., 2017). Three studies investigated the impact of outreach campaigns conducted by CHWs (Edward et al., 2007; Giugliani et al., 2014; Brault et al., 2018). These studies reported expanded access to care and improved referrals, which resulted in reductions in under-five mortality and infant mortality. Other interventions reported efforts to strengthen basic health services (Newbrander et al., 2014; Healey et al., 2021) and case management for combined maternal and child health programming (Luckow et al., 2017; Oo, 2018; Healey et al., 2021).

Leveraging communities for epidemic control efforts were explored in two papers, and evidence indicated that CHWs were more timely than professional healthcare data entry clerks and played a key role in community triage for Ebola patients (Abramowitz et al., 2015). As such, they may be well suited to report outbreaks in near real time (Stijntjes, 2015).

Two studies evaluated the capacity of task sharing to CHW cadres with lower literacy levels to deliver care specifically related to nutrition care. Simplified treatment protocols strategies were found to improve weight-for-age scores (Mayhew et al., 2014), average diastolic blood pressure after hypertension and diabetes diagnosis (Zou et al., 2020) and performance checklists use (Van Boetzelaer et al., 2019).

Key functions of CHWs

Our review identified evidence regarding four key functions of CHWs in healthcare delivery in post-conflict settings including (1) access to care and treatment coverage, (2) case management and adherence support, (3) disease detection and monitoring and (4) scaling up of services. Further details of the types of strategies reported for each function, which reported measurable impacts, are provided in Table 3 (see Annexe).

Reported impact outcomes by CHW key health care delivery function

| Author (year) . | Intervention . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Access to care and treatment coverage | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +135% treatment coverage |

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies for Ebola | + access to care |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Group psychotherapy | No effect on burden of depression and anxiety symptoms + in positive coping strategy use |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Group psychotherapy | -Decreased PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Group psychotherapy | -Lowered scores for anxiety and depressive symptoms |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Community health home visits | −66% in infant mortality −62% in under-five mortality |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Female CHW presence in community | +53.9% coverage of women receiving antennal care +10.3% women receiving tetanus toxoid injections |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | CHWs as link to formal healthcare services | No reported outcomes |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | iCCM | +34.7% children receiving antibiotics for pneumonia +41% receiving oral rehydration solutions for diarrhoea |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Community-based group learning and counselling | + in knowledge of reproductive control methods |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +3.8% antiretroviral therapy treatment coverage TB: +35.5% treatment coverage |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | -decreased PTSD symptoms on self-reported score (−9.26) and caregiver-reported measures (3.53) -symptom reduction (−26.41) |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Community-based TB care | Contributed to detection of 36% of total new TB cases in respective townships |

| Smith et al. (2014a, b) | Advance distribution of misoprostol | +20% more likely for women to ingest misoprostol at correct time + increased coverage of misoprostol use |

| Case management and adherence support | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +86% treatment success |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +22.2% patient retention and −6% LTFU TB: −7.5% LTFU |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | iCCM | −69% of severe pneumonia cases −21% to −52% under-five mortality |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | CHW case management | 98.9% of positive malaria cases appropriately treated |

| White et al. (2018) | iCCM | + childhood disease treatment by qualified provider + correct diarrhoeal treatment |

| Disease detection and monitoring | ||

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Rapid diagnostic testing | + identification of malaria in febrile children |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Training CHW to identify suspected cases of leprosy | +25% new cases reported −6.2% disability rate of new cases |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Community growth monitoring | + weight-for-age scores by 0.3 |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | Train CHWs to recognize potential syndromic cases of HAT during routine outpatient practice | + appropriate referrals |

| Stijntjes et al. (2015) | CHW smart phone-based data entry for disease surveillance | + timeliness of detecting disease outbreak |

| Zou et al. (2020) | Training CHWs to improve diagnosing NCDs | + average diastolic blood pressure of hypertensive/diabetic patients by 8 mmHg |

| Scaling up services | ||

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies | + access to care |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Tablet-based health video library | + patients seeking reproductive maternal and child health counselling |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Training non-specialists to integrate mental health care into primary care | + in demonstrated knowledge |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision to train CHWs | No change reported |

| Van Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | Simplified treatment protocol for CHWs | + 2% improvement in malnutrition checklist completion |

| Author (year) . | Intervention . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Access to care and treatment coverage | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +135% treatment coverage |

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies for Ebola | + access to care |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Group psychotherapy | No effect on burden of depression and anxiety symptoms + in positive coping strategy use |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Group psychotherapy | -Decreased PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Group psychotherapy | -Lowered scores for anxiety and depressive symptoms |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Community health home visits | −66% in infant mortality −62% in under-five mortality |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Female CHW presence in community | +53.9% coverage of women receiving antennal care +10.3% women receiving tetanus toxoid injections |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | CHWs as link to formal healthcare services | No reported outcomes |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | iCCM | +34.7% children receiving antibiotics for pneumonia +41% receiving oral rehydration solutions for diarrhoea |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Community-based group learning and counselling | + in knowledge of reproductive control methods |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +3.8% antiretroviral therapy treatment coverage TB: +35.5% treatment coverage |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | -decreased PTSD symptoms on self-reported score (−9.26) and caregiver-reported measures (3.53) -symptom reduction (−26.41) |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Community-based TB care | Contributed to detection of 36% of total new TB cases in respective townships |

| Smith et al. (2014a, b) | Advance distribution of misoprostol | +20% more likely for women to ingest misoprostol at correct time + increased coverage of misoprostol use |

| Case management and adherence support | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +86% treatment success |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +22.2% patient retention and −6% LTFU TB: −7.5% LTFU |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | iCCM | −69% of severe pneumonia cases −21% to −52% under-five mortality |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | CHW case management | 98.9% of positive malaria cases appropriately treated |

| White et al. (2018) | iCCM | + childhood disease treatment by qualified provider + correct diarrhoeal treatment |

| Disease detection and monitoring | ||

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Rapid diagnostic testing | + identification of malaria in febrile children |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Training CHW to identify suspected cases of leprosy | +25% new cases reported −6.2% disability rate of new cases |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Community growth monitoring | + weight-for-age scores by 0.3 |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | Train CHWs to recognize potential syndromic cases of HAT during routine outpatient practice | + appropriate referrals |

| Stijntjes et al. (2015) | CHW smart phone-based data entry for disease surveillance | + timeliness of detecting disease outbreak |

| Zou et al. (2020) | Training CHWs to improve diagnosing NCDs | + average diastolic blood pressure of hypertensive/diabetic patients by 8 mmHg |

| Scaling up services | ||

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies | + access to care |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Tablet-based health video library | + patients seeking reproductive maternal and child health counselling |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Training non-specialists to integrate mental health care into primary care | + in demonstrated knowledge |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision to train CHWs | No change reported |

| Van Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | Simplified treatment protocol for CHWs | + 2% improvement in malnutrition checklist completion |

+ indicates increase; − indicates decrease; HAT = human African trypanosomiasis; LTFU = loss to follow-up; NCDs = noncommunicable diseases; TB = tuberculosis; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reported impact outcomes by CHW key health care delivery function

| Author (year) . | Intervention . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Access to care and treatment coverage | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +135% treatment coverage |

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies for Ebola | + access to care |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Group psychotherapy | No effect on burden of depression and anxiety symptoms + in positive coping strategy use |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Group psychotherapy | -Decreased PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Group psychotherapy | -Lowered scores for anxiety and depressive symptoms |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Community health home visits | −66% in infant mortality −62% in under-five mortality |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Female CHW presence in community | +53.9% coverage of women receiving antennal care +10.3% women receiving tetanus toxoid injections |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | CHWs as link to formal healthcare services | No reported outcomes |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | iCCM | +34.7% children receiving antibiotics for pneumonia +41% receiving oral rehydration solutions for diarrhoea |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Community-based group learning and counselling | + in knowledge of reproductive control methods |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +3.8% antiretroviral therapy treatment coverage TB: +35.5% treatment coverage |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | -decreased PTSD symptoms on self-reported score (−9.26) and caregiver-reported measures (3.53) -symptom reduction (−26.41) |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Community-based TB care | Contributed to detection of 36% of total new TB cases in respective townships |

| Smith et al. (2014a, b) | Advance distribution of misoprostol | +20% more likely for women to ingest misoprostol at correct time + increased coverage of misoprostol use |

| Case management and adherence support | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +86% treatment success |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +22.2% patient retention and −6% LTFU TB: −7.5% LTFU |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | iCCM | −69% of severe pneumonia cases −21% to −52% under-five mortality |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | CHW case management | 98.9% of positive malaria cases appropriately treated |

| White et al. (2018) | iCCM | + childhood disease treatment by qualified provider + correct diarrhoeal treatment |

| Disease detection and monitoring | ||

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Rapid diagnostic testing | + identification of malaria in febrile children |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Training CHW to identify suspected cases of leprosy | +25% new cases reported −6.2% disability rate of new cases |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Community growth monitoring | + weight-for-age scores by 0.3 |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | Train CHWs to recognize potential syndromic cases of HAT during routine outpatient practice | + appropriate referrals |

| Stijntjes et al. (2015) | CHW smart phone-based data entry for disease surveillance | + timeliness of detecting disease outbreak |

| Zou et al. (2020) | Training CHWs to improve diagnosing NCDs | + average diastolic blood pressure of hypertensive/diabetic patients by 8 mmHg |

| Scaling up services | ||

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies | + access to care |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Tablet-based health video library | + patients seeking reproductive maternal and child health counselling |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Training non-specialists to integrate mental health care into primary care | + in demonstrated knowledge |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision to train CHWs | No change reported |

| Van Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | Simplified treatment protocol for CHWs | + 2% improvement in malnutrition checklist completion |

| Author (year) . | Intervention . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Access to care and treatment coverage | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +135% treatment coverage |

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies for Ebola | + access to care |

| Bass et al. (2012) | Group psychotherapy | No effect on burden of depression and anxiety symptoms + in positive coping strategy use |

| Bass et al. (2013) | Group psychotherapy | -Decreased PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Bass et al. (2016) | Group psychotherapy | -Lowered scores for anxiety and depressive symptoms |

| Edmond et al. (2018) | Community health home visits | −66% in infant mortality −62% in under-five mortality |

| Hadi et al. (2007) | Female CHW presence in community | +53.9% coverage of women receiving antennal care +10.3% women receiving tetanus toxoid injections |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Musinguzi et al. (2017) | CHWs as link to formal healthcare services | No reported outcomes |

| Nanyonjo (2014) | iCCM | +34.7% children receiving antibiotics for pneumonia +41% receiving oral rehydration solutions for diarrhoea |

| Ojanduru et al. (2018) | Community-based group learning and counselling | + in knowledge of reproductive control methods |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +3.8% antiretroviral therapy treatment coverage TB: +35.5% treatment coverage |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy | -decreased PTSD symptoms on self-reported score (−9.26) and caregiver-reported measures (3.53) -symptom reduction (−26.41) |

| Soe et al. (2017) | Community-based TB care | Contributed to detection of 36% of total new TB cases in respective townships |

| Smith et al. (2014a, b) | Advance distribution of misoprostol | +20% more likely for women to ingest misoprostol at correct time + increased coverage of misoprostol use |

| Case management and adherence support | ||

| Ahmadzai et al. (2008) | Directly observed treatment (DOTS) for TB | +86% treatment success |

| Rogers et al. (2018) | Community-based treatment and social assistance | HIV/AIDS: +22.2% patient retention and −6% LTFU TB: −7.5% LTFU |

| Marsh et al. (2012) | iCCM | −69% of severe pneumonia cases −21% to −52% under-five mortality |

| Ruckstuhl et al. (2017) | CHW case management | 98.9% of positive malaria cases appropriately treated |

| White et al. (2018) | iCCM | + childhood disease treatment by qualified provider + correct diarrhoeal treatment |

| Disease detection and monitoring | ||

| Hawkes et al. (2009) | Rapid diagnostic testing | + identification of malaria in febrile children |

| Kasang et al. (2019) | Training CHW to identify suspected cases of leprosy | +25% new cases reported −6.2% disability rate of new cases |

| Mayhew et al. (2014) | Community growth monitoring | + weight-for-age scores by 0.3 |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | Train CHWs to recognize potential syndromic cases of HAT during routine outpatient practice | + appropriate referrals |

| Stijntjes et al. (2015) | CHW smart phone-based data entry for disease surveillance | + timeliness of detecting disease outbreak |

| Zou et al. (2020) | Training CHWs to improve diagnosing NCDs | + average diastolic blood pressure of hypertensive/diabetic patients by 8 mmHg |

| Scaling up services | ||

| Abramowitz et al. (2015) | Community-based epidemic control strategies | + access to care |

| Dal Santo et al. (2020) | Tablet-based health video library | + patients seeking reproductive maternal and child health counselling |

| Huber et al. (2010) | CHW presence in community | +10% increased use of contraceptives |

| Kohrt et al. (2018) | Training non-specialists to integrate mental health care into primary care | + in demonstrated knowledge |

| Rahman et al. (2019a) | Tablet-based training application and cascaded supervision to train CHWs | No change reported |

| Van Boetzelaer et al. (2019) | Simplified treatment protocol for CHWs | + 2% improvement in malnutrition checklist completion |

+ indicates increase; − indicates decrease; HAT = human African trypanosomiasis; LTFU = loss to follow-up; NCDs = noncommunicable diseases; TB = tuberculosis; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Access to care and treatment coverage

Fifteen studies reported outcomes related to access to care and treatment coverage and revealed that CHW interventions are highly successful at reducing treatment gap for populations in hard-to-reach conflict-affected areas. Many interventions were both feasible and successful in raising awareness among communities, which in turn may improve access to care, increase treatment coverage and link and connect communities to formal healthcare services (Hadi et al., 2007; Musinguzi et al., 2017; Soe et al., 2017; Ojanduru et al., 2018). Studies found improved coverage of care, measured by an increase in the number of patients receiving care services. This improvement in access was particularly notable in studies focused on services for reproductive and maternal health and psychosocial support.

Of particular significance, several studies suggest that CHW interventions were able to provide mental healthcare for individuals residing in FCAPCS, where residents are especially prone to post-traumatic stress. For example, one study evaluated the impact of a trauma-informed support, skills and psychoeducation intervention provided by CHWs in northern Iraq on depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress and anxiety (Bass et al., 2016). Study results revealed that the intervention has a statistically significant and moderate-sized effect on depression symptoms and a small effect on post-traumatic stress and anxiety.

Case management and adherence support

Nine studies in our review identified the benefits of CHW case management and supportive care in improving health behaviours of the population. CHWs contributed to routine clinical care and treatment adherence support approaches such as directly observed treatment (Ahmadzai et al., 2008; Fiekert, 2002; Rogers et al., 2018; Wickett et al., 2018) and case management (Ruckstuhl et al., 2017; Ferdinand et al., 2020). In all instances, the percentage of patients receiving treatment increased, while patient attrition or loss to follow-up dropped dramatically.

For example, one study found that CHWs trained in case management resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of children receiving care from formal care providers (Luckow et al., 2017). More specifically, the study found that care for diarrhoea increased by 60 percentage points, care for fever increased by 31 percentage points and care for acute respiratory infection increased by 51 percentage points. Adherence support delivered by CHWs was found to decrease loss to follow-up in HIV patients by 6 percentage points and increase patient retention of ART treatment by 22 percentage points (Rogers et al., 2018). In Liberia, one study found loss to follow-up rates decreased by 76% as a result of accompaniment assistance to patients with TB (Wickett et al., 2018); this change is highly impactful as TB is highly curable with uninterrupted antituberculosis therapies.

Disease detection and monitoring

Eight studies reported on disease detection and monitoring efforts for infectious diseases. Our review found evidence that CHWs lead to more widespread appropriate referrals for Gambiense-type human African trypanosomiasis (Palmer et al., 2014) and malaria (Ferdinand et al., 2020). Similar results were noted for improvements in new case detection of leprosy (Kasang et al., 2019). Using CHWs to actively search and identify cases and provide referrals was found to increase in new case detection (Soe et al., 2017; Kasang et al., 2019), lead to more widespread appropriate referrals (Palmer et al., 2014) and raise community awareness of disease (Soe et al., 2017).

The advantage of engaging CHWs was also evident in disease surveillance efforts. For example, one study showed that CHWs are likely to detect outbreaks in a timelier fashion than untrained public health data enterers (Stijntjes, 2015). Concomitantly, CHWs trained to screen and identify disease were then able to link communities to more formal care.

Scaling up services

CHWs were found to contribute to the scaling up of healthcare services in two major ways. The first is by means of their location and integration into the community in hard-to-reach areas, making it easier for them to provide faster care. This pattern is highlighted by Stijntjes (2015); CHWs have the capacity to conduct near-real-time disease surveillance quicker than professional data enterers (Stijntjes, 2015). In addition, Abramowitz et al. (2015) reported similar results, noting that locally engaged community members were able to address absences of infrastructure and material support in order to contain the Ebola epidemic in their communities (Abramowitz et al., 2015).

The second mechanism through which CHWs contributed to scaling up of health services was through task shifting and task sharing. Of studies included in this review, four evaluated CHWs’ abilities to share healthcare tasks with formally trained workers (Mayhew et al., 2014; Stijntjes, 2015; Van Boetzelaer et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2020). In all cases, CHWs were found to excel in providing healthcare tasks, or surveillance, that are normally provided by formally trained workers. CHWs were determined to be useful, particularly in instances of uncomplicated care, such as certain cases of malnutrition or other common instances of care. For example, in Afghanistan, one study found that community-based growth monitoring and promotion—delivered by lower literacy female CHWs—improved children’s weight-for-age scores by 0.3 standard deviations from the mean (Mayhew et al., 2014).

Discussion

This systematic review described and summarized the body of literature pertaining to CHW healthcare delivery in fragile and conflict-affected settings. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify systematically the evidence of CHWs’ impact on enhancing healthcare and rebuilding the health system after a period of conflict. Studies indicated that community-based efforts may address key barriers to delivering care in the context of disrupted health systems by facilitating access to care, strengthening disease detection and improving adherence to care. Our results align with the broader literature on the success of CHWs and point to a particular value of these interventions in the context of post-conflict settings.

We identified studies that point to the value of leveraging CHWs to deliver healthcare and serve the unique health needs of populations residing in fragile and conflict-affected settings. Studies indicate that CHWs could (1) increase access to essential healthcare services, (2) improve case management and treatment adherence, (3) enhance disease detection and monitoring and (4) facilitate the scaling up of services.

Evidence suggests that CHW interventions are successful at addressing the treatment gap for populations in hard-to-reach conflict-affected areas. More specifically, CHWs were able to provide mental healthcare for individuals residing in FCAPCS, where residents are especially prone to post-traumatic stress. Health outcomes are improved with adherence to treatment regimens, which require consistent access to medicines and can be complicated by the ongoing insecurity in FCAPCS. Engaging a network of CHWs, who are already embedded in the community, to collect health information and report disease outbreaks may lead to earlier detection and better monitoring where health information infrastructure may be severely weakened. CHWs may be an effective resource in detecting new cases of infectious diseases.

Despite fractured health systems in FCAPCS, scalable CHW interventions were documented to improve the availability of services and accessibility to care. Task shifting, or task sharing, from more specialized healthcare workers to a broader base of CHWs can directly ameliorate supply-side issues. As such, task shifting and sharing protocols may allow CHWs to specialize in specific tasks where they have comparative advantage, thus freeing up more time for formally trained health workers to complete more complicated tasks.

iCCM interventions, which train and deploy CHWs to hard-to-reach areas, are frequently implemented in many low- and middle-income countries (Guenther et al., 2014). This systematic review adds to the literature by identifying and including four studies (out of 55) on the effect of iCCM interventions in fragile states and conflict-affected areas. These studies found that the iCCM intervention increased (1) treatment by qualified provider, (2) coverage of appropriate treatment of fevers and (3) the proportion of children with pneumonia who received antibiotics and oral rehydration salts among children with diarrhoea. Another observed benefit was improved quality of services, measured both by patient perception and adherence to guidelines, as a result of delivering more appropriate care (Nanyonjo, 2014; Ratnayake et al., 2017; Oo, 2018). With 39.8% of those living in FCAPCS under the age of 15, childhood diseases appear to particularly benefit from case management by CHWs (World Health Organization, 2017).