-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jonathan Campion, Claire Coombes, Neel Bhaduri, Mental health coverage in needs assessments and associated opportunities, Journal of Public Health, Volume 39, Issue 4, December 2017, Pages 813–820, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw125

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mental disorders account for almost a third of UK disease burden. Cost effective public mental health interventions have broad public health relevant impacts. Since coverage of such interventions is low, assessment of local coverage is important.

A total of 23 Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNAs) around London were assessed for different mental health intelligence.

Mental health was poorly covered and difficult to locate in JSNAs. Only a minority of JSNAs mentioned most mental disorders while far fewer JSNAs provided local prevalence estimates or numbers receiving treatment. Only 6% JSNAs included local wellbeing levels and any mental wellbeing promotion initiative mentioned included no information about coverage. Most JSNAs provided little information about impact of mental disorder or broader determinants on mental health. No JSNAs included associated economic implications or information about size of mental health unmet need.

Lack of mental health representation in JSNAs means local authorities and clinical commissioning groups cannot perform statutory duties to assess local health needs to inform strategic development and commissioning. This perpetuates poor coverage of public mental health interventions. Actions to improve mental health representation in JSNAs are suggested. Improved coverage of such interventions will result in broad public health relevant impacts and associated economic savings.

Introduction

Mental disorder and wellbeing have large population impacts. The proportion of disease burden (as measured by years lived with disability) due to mental disorders and self-harm is 25.5% globally, 29.2% in Europe and 30.3% in UK1 although even this is a significant underestimate since it excludes several mental disorders. Such a burden has an annual economic cost of £105 billion in England2 and €523.2 billion in the EU.3 The large impact of mental disorder is due to a combination of high prevalence rates with almost one in four people in UK experiencing at least one mental disorder each year,4 the majority of lifetime mental disorder arising by early adulthood, and a broad range of impacts across the life-course including in public health and non-health sectors.5 Taking the example of smoking which is the single largest cause of preventable death and a public health priority, 43% of smokers aged 11–16 years in the UK have either emotional or conduct disorder6 while 42% of adult tobacco consumption in England is by people with mental disorder.7 Poor mental wellbeing also has a broad range of impacts5 with 4.8% of England's adult population experiencing low satisfaction, 3.8% feeling life not being worthwhile and 8.9% having low happiness levels.8

A range of effective public mental health interventions exist to treat mental disorder, prevent mental disorder from arising and promote wellbeing.5,9 Such interventions also prevent a broad range of impacts relevant to public health including health risk behaviour, physical illness and 10–20 years lower life expectancy. Since most lifetime mental disorder arises before adulthood, early treatment can also prevent a range of public health adverse outcomes across adulthood. However, only a minority of those with mental disorder (except psychosis) in UK receives treatment4,6 while provision of interventions to address associated health risk behaviour and physical illness, or to prevent mental disorder is even more limited.10,11 Similarly, although mental wellbeing has a broad range of impacts, provision of interventions to promote mental wellbeing is extremely limited. Since public mental health interventions result in associated economic savings even in the short term as outlined in the most recent mental health strategy,12 this intervention gap also results in significant economic costs across different sectors.

Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNAs) should provide information about local levels of health and social care needs and their broader determinants to enable local authorities, NHS and partners to provide the most appropriate services to meet those needs.13 The Health and Social Care Act (2012) introduced duties and powers for health and wellbeing boards in relation to JSNAs and Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies (JHWSs) which support clinical leadership and elected leaders to deliver the best health and care services based on evidence of local needs. Local authorities and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) have equal and joint duties to prepare JSNAs and JHWSs through their health and wellbeing boards. Such assessments should include mental disorder and wellbeing particularly in view of the large impact of mental disorder and poor mental wellbeing as well as the poor coverage of public mental health interventions.

Methods

This audit assessed level of inclusion of mental health in JSNAs of 23 local authorities covering more than 6 million people across north London and the surrounding region. An online search for JSNAs was conducted during October and November, 2013. JSNAs were then assessed for accessibility, length, organization and structure. Inclusion of different types of mental health intelligence outlined in public mental health commissioning guidance9 was undertaken. Any uncertainty was checked with a second researcher and agreement then reached. Mental health intelligence required in a JSNA is further outlined in the discussion section.

Results

Online access to JSNAs

An online search located JSNAs for 72% (18/23) of local authorities. However, mental health information within JSNAs was both difficult and time consuming to locate due to JSNAs comprising numerous, lengthy documents without consistent format. Most JSNAs exceeded 400 pages for each local authority with the largest JSNA consisting of 76 documents and 3263 pages. Periods of time covered by JSNAs ranged from 2010 to 2015. Where information was provided, sources were inconsistently cited with lack of clarity about when information was updated.

Coverage of mental health in JSNAs

The proportion of the population affected by different mental disorders and the proportion of JSNAs including different types of mental health intelligence is shown in Table 1. Only a minority of JSNAs mentioned most mental disorders despite their prevalence and existence of evidence based treatment. However, for many JSNAs, mental disorders were only represented as figures in Tables and not covered in further detail: for child and adolescent mental disorder, only drug misuse was mentioned in more than 50% of JSNAs. Although the proportion of adult mental disorders mentioned in more than 50% of JSNAs included depression (72%), psychosis (67%), dementia (100%), alcohol dependence (83%), drug dependence (78%) and suicide (100%), seven other mental disorders were mentioned in less than 50% of JSNAs.

Proportion of the population affected by different mental disorder and proportion of JSNAs including different mental disorder and wellbeing, providing local prevalence estimates and numbers receiving intervention

| Age group . | Mental disorder or wellbeing area . | % Affected nationally . | % Of JSNAs mentioning different mental disorder and wellbeing (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local prevalence estimates (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local numbers receiving intervention (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent mental disorder | Conduct disorder | 5.9%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 |

| Emotional disorder | 3.5%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 | |

| Hyperkinetic disorder | 1.5%6 | 44 | 39 | 0 | |

| Anxiety and depression | 3.5%6 | 17 | 11 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 13.2 | 22 | 6 | 0 | |

| Autism | 1.6% | 44 | 22 | 0 | |

| Less common mental disorders | 1% | 28 | 28 | 0 | |

| Alcohol use | 9%6 | 50 | 33 | 39 | |

| Drug misuse | 8%6 | 55 | 39 | 50 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 6%6 | 39 | 39 | 11 | |

| Adult mental disorder | Depression | 3.3%4 | 72 | 50 | 22 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 5.9%4 | 28 | 17 | 0 | |

| Phobias | 2.4%4 | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1.3%4 | 44 | 17 | 0 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4.4%4 | 27 | 0 | 0 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 9.7%4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Psychosis/ serious mental illness | 0.7%4 | 67 | 33 | 56 | |

| Personality disorder | 13.7%4 | 28 | 6 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 6.4% | 11 | 6 | 0 | |

| Dementia | 5.0%14 | 100 | 89 | 28 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.2%4 | 83 | 61 | 72 | |

| Drug dependence | 3.1%4 | 78 | 61 | 61 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 18%15 | 100 | 78 | 33 | |

| Suicide | 10.8/100 00016 | 100 | 72 | N/A | |

| Adult mental wellbeing | Mental wellbeing (qualitative explanation) | 44 | 68 | 0 |

| Age group . | Mental disorder or wellbeing area . | % Affected nationally . | % Of JSNAs mentioning different mental disorder and wellbeing (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local prevalence estimates (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local numbers receiving intervention (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent mental disorder | Conduct disorder | 5.9%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 |

| Emotional disorder | 3.5%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 | |

| Hyperkinetic disorder | 1.5%6 | 44 | 39 | 0 | |

| Anxiety and depression | 3.5%6 | 17 | 11 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 13.2 | 22 | 6 | 0 | |

| Autism | 1.6% | 44 | 22 | 0 | |

| Less common mental disorders | 1% | 28 | 28 | 0 | |

| Alcohol use | 9%6 | 50 | 33 | 39 | |

| Drug misuse | 8%6 | 55 | 39 | 50 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 6%6 | 39 | 39 | 11 | |

| Adult mental disorder | Depression | 3.3%4 | 72 | 50 | 22 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 5.9%4 | 28 | 17 | 0 | |

| Phobias | 2.4%4 | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1.3%4 | 44 | 17 | 0 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4.4%4 | 27 | 0 | 0 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 9.7%4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Psychosis/ serious mental illness | 0.7%4 | 67 | 33 | 56 | |

| Personality disorder | 13.7%4 | 28 | 6 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 6.4% | 11 | 6 | 0 | |

| Dementia | 5.0%14 | 100 | 89 | 28 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.2%4 | 83 | 61 | 72 | |

| Drug dependence | 3.1%4 | 78 | 61 | 61 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 18%15 | 100 | 78 | 33 | |

| Suicide | 10.8/100 00016 | 100 | 72 | N/A | |

| Adult mental wellbeing | Mental wellbeing (qualitative explanation) | 44 | 68 | 0 |

Proportion of the population affected by different mental disorder and proportion of JSNAs including different mental disorder and wellbeing, providing local prevalence estimates and numbers receiving intervention

| Age group . | Mental disorder or wellbeing area . | % Affected nationally . | % Of JSNAs mentioning different mental disorder and wellbeing (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local prevalence estimates (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local numbers receiving intervention (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent mental disorder | Conduct disorder | 5.9%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 |

| Emotional disorder | 3.5%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 | |

| Hyperkinetic disorder | 1.5%6 | 44 | 39 | 0 | |

| Anxiety and depression | 3.5%6 | 17 | 11 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 13.2 | 22 | 6 | 0 | |

| Autism | 1.6% | 44 | 22 | 0 | |

| Less common mental disorders | 1% | 28 | 28 | 0 | |

| Alcohol use | 9%6 | 50 | 33 | 39 | |

| Drug misuse | 8%6 | 55 | 39 | 50 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 6%6 | 39 | 39 | 11 | |

| Adult mental disorder | Depression | 3.3%4 | 72 | 50 | 22 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 5.9%4 | 28 | 17 | 0 | |

| Phobias | 2.4%4 | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1.3%4 | 44 | 17 | 0 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4.4%4 | 27 | 0 | 0 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 9.7%4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Psychosis/ serious mental illness | 0.7%4 | 67 | 33 | 56 | |

| Personality disorder | 13.7%4 | 28 | 6 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 6.4% | 11 | 6 | 0 | |

| Dementia | 5.0%14 | 100 | 89 | 28 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.2%4 | 83 | 61 | 72 | |

| Drug dependence | 3.1%4 | 78 | 61 | 61 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 18%15 | 100 | 78 | 33 | |

| Suicide | 10.8/100 00016 | 100 | 72 | N/A | |

| Adult mental wellbeing | Mental wellbeing (qualitative explanation) | 44 | 68 | 0 |

| Age group . | Mental disorder or wellbeing area . | % Affected nationally . | % Of JSNAs mentioning different mental disorder and wellbeing (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local prevalence estimates (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local numbers receiving intervention (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent mental disorder | Conduct disorder | 5.9%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 |

| Emotional disorder | 3.5%6 | 50 | 44 | 0 | |

| Hyperkinetic disorder | 1.5%6 | 44 | 39 | 0 | |

| Anxiety and depression | 3.5%6 | 17 | 11 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 13.2 | 22 | 6 | 0 | |

| Autism | 1.6% | 44 | 22 | 0 | |

| Less common mental disorders | 1% | 28 | 28 | 0 | |

| Alcohol use | 9%6 | 50 | 33 | 39 | |

| Drug misuse | 8%6 | 55 | 39 | 50 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 6%6 | 39 | 39 | 11 | |

| Adult mental disorder | Depression | 3.3%4 | 72 | 50 | 22 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 5.9%4 | 28 | 17 | 0 | |

| Phobias | 2.4%4 | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1.3%4 | 44 | 17 | 0 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4.4%4 | 27 | 0 | 0 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 9.7%4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Psychosis/ serious mental illness | 0.7%4 | 67 | 33 | 56 | |

| Personality disorder | 13.7%4 | 28 | 6 | 0 | |

| Eating disorder | 6.4% | 11 | 6 | 0 | |

| Dementia | 5.0%14 | 100 | 89 | 28 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.2%4 | 83 | 61 | 72 | |

| Drug dependence | 3.1%4 | 78 | 61 | 61 | |

| Tobacco smoking | 18%15 | 100 | 78 | 33 | |

| Suicide | 10.8/100 00016 | 100 | 72 | N/A | |

| Adult mental wellbeing | Mental wellbeing (qualitative explanation) | 44 | 68 | 0 |

The proportion of JSNAs providing local estimates of different mental disorder was lower with less than half of JSNAs providing any estimates for any child and adolescent mental disorder and more than 50% of JSNAs for only six adult mental disorders (Table 1). However, local prevalence estimates usually applied national rates rather than taking into account local factors. For instance, no prevalence estimates of child and adolescent mental disorder took account of local deprivation levels which are associated with 3-fold variation in prevalence across the UK.6

The proportion of JSNAs including local treatment levels was even lower and information was usually insufficient to provide information about the level of unmet need (Table 1). No JSNAs included information about numbers receiving treatment for different child and adolescent mental disorder except for smoking, alcohol and drug misuse although most JSNA's did provide overall referral numbers to CAMHS and inpatient admissions rates. JSNAs providing local numbers receiving treatment occurred for only six adult mental disorders.

Almost half JSNAs mentioned mental wellbeing although only 6% included local estimated levels from the annual national ONS wellbeing survey.8 If mental wellbeing promotion initiatives were mentioned, they were done so in passing with no reference to numbers receiving intervention.

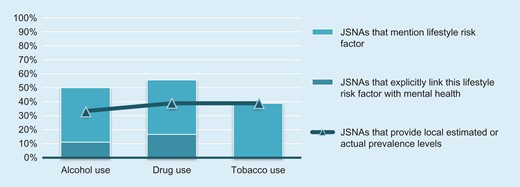

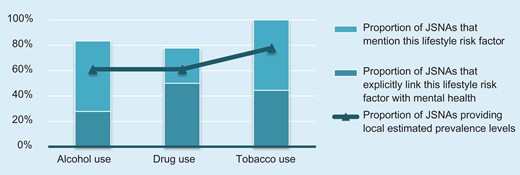

Impact of mental health in other areas

Most JSNAs provided little information about impact of broader determinants on mental health required by statutory guidance13 or how poor mental health impacts on other areas. This was particularly the case for mental disorder and alcohol/drug/tobacco misuse. For instance, no JSNAs linked smoking to child and adolescent mental disorder despite 43% of smokers aged 11−16 years having either emotional or conduct disorder.6,10 Similarly, although drug and alcohol misuse is several times more common in children and adolescents with mental disorder,6,10 alcohol misuse was linked to mental disorder in 11% of JSNAs while drug misuse was linked to mental disorder in 16% of JSNAs (Fig. 1). For adults, only 44% of JSNA's linked adult smoking to mental disorder and no JSNA provided information on smoking cessation coverage for this group despite 42% of adult tobacco consumption in England being by those with mental disorder.7 Only 28% of JSNAs linked alcohol misuse to mental disorder while no JSNAs linked drug misuse to mental disorder (Fig. 2).

Proportion of JSNAs which included information about child and adolescent alcohol, drug and tobacco use.

Proportion of JSNAs which included information about adult alcohol, drug and tobacco use.

Higher risk groups

Particular groups are at several fold increased risk of mental disorder and poor mental wellbeing5,10 and are also protected by inequality legislation. Such groups require representation in needs assessments to facilitate targeted approaches and prevent widening of inequalities. Proportion of JSNAs including different types of mental health intelligence is outlined in Table 2. Child and adolescent higher risk groups were mentioned on average in 61% of JSNAs with local estimated numbers from such groups mentioned in 50% of JSNAs although the link to higher risk of mental disorder was made in only 23%. Adult higher risk groups were mentioned in 58% of JSNAs with local estimated numbers from such groups mentioned in 41% of JSNAs although the link to higher risk of mental disorder was made in only 29% of JSNAs. No JSNA provided sufficient information about the level of unmet need for higher risk groups.

Proportion of JSNAs which included different higher risk groups, provided local estimates of such groups and specifically linked such groups to mental disorder

| Age group . | Higher risk group . | % Of JSNAs mentioning higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local estimates of higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs linking higher risk group to mental disorder (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent higher risk groups | Child poverty/deprivation | 66 | 56 | 22 |

| Looked after children | 56 | 50 | 28 | |

| Special educational need | 56 | 11 | 17 | |

| Disabilities | 66 | 50 | 33 | |

| Parents with mental disorder | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Parents or caregivers in prison | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Not in employment, education or training | 83 | 83 | 44 | |

| Teenage pregnancy | 100 | 100 | 33 | |

| Young carers | 50 | 44 | 22 | |

| Young offenders | 50 | 33 | 28 | |

| Adult higher risk groups | Long term physical conditions | 89 | 61 | 22 |

| Carers | 67 | 50 | 33 | |

| Post-natal depression | 28 | 17 | N/A | |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender | 33 | 22 | 28 | |

| Unemployed or benefit claimants | 72 | 67 | 56 | |

| Adults without qualifications | 56 | 56 | 17 | |

| Homeless | 89 | 72 | 33 | |

| Prisoners and offenders | 22 | 0 | 17 | |

| Refugees/ asylum seekers | 39 | 17 | 22 | |

| Dementia | 100 | 89 | 28 |

| Age group . | Higher risk group . | % Of JSNAs mentioning higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local estimates of higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs linking higher risk group to mental disorder (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent higher risk groups | Child poverty/deprivation | 66 | 56 | 22 |

| Looked after children | 56 | 50 | 28 | |

| Special educational need | 56 | 11 | 17 | |

| Disabilities | 66 | 50 | 33 | |

| Parents with mental disorder | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Parents or caregivers in prison | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Not in employment, education or training | 83 | 83 | 44 | |

| Teenage pregnancy | 100 | 100 | 33 | |

| Young carers | 50 | 44 | 22 | |

| Young offenders | 50 | 33 | 28 | |

| Adult higher risk groups | Long term physical conditions | 89 | 61 | 22 |

| Carers | 67 | 50 | 33 | |

| Post-natal depression | 28 | 17 | N/A | |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender | 33 | 22 | 28 | |

| Unemployed or benefit claimants | 72 | 67 | 56 | |

| Adults without qualifications | 56 | 56 | 17 | |

| Homeless | 89 | 72 | 33 | |

| Prisoners and offenders | 22 | 0 | 17 | |

| Refugees/ asylum seekers | 39 | 17 | 22 | |

| Dementia | 100 | 89 | 28 |

Proportion of JSNAs which included different higher risk groups, provided local estimates of such groups and specifically linked such groups to mental disorder

| Age group . | Higher risk group . | % Of JSNAs mentioning higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local estimates of higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs linking higher risk group to mental disorder (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent higher risk groups | Child poverty/deprivation | 66 | 56 | 22 |

| Looked after children | 56 | 50 | 28 | |

| Special educational need | 56 | 11 | 17 | |

| Disabilities | 66 | 50 | 33 | |

| Parents with mental disorder | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Parents or caregivers in prison | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Not in employment, education or training | 83 | 83 | 44 | |

| Teenage pregnancy | 100 | 100 | 33 | |

| Young carers | 50 | 44 | 22 | |

| Young offenders | 50 | 33 | 28 | |

| Adult higher risk groups | Long term physical conditions | 89 | 61 | 22 |

| Carers | 67 | 50 | 33 | |

| Post-natal depression | 28 | 17 | N/A | |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender | 33 | 22 | 28 | |

| Unemployed or benefit claimants | 72 | 67 | 56 | |

| Adults without qualifications | 56 | 56 | 17 | |

| Homeless | 89 | 72 | 33 | |

| Prisoners and offenders | 22 | 0 | 17 | |

| Refugees/ asylum seekers | 39 | 17 | 22 | |

| Dementia | 100 | 89 | 28 |

| Age group . | Higher risk group . | % Of JSNAs mentioning higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs providing local estimates of higher risk group (%) . | % Of JSNAs linking higher risk group to mental disorder (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and adolescent higher risk groups | Child poverty/deprivation | 66 | 56 | 22 |

| Looked after children | 56 | 50 | 28 | |

| Special educational need | 56 | 11 | 17 | |

| Disabilities | 66 | 50 | 33 | |

| Parents with mental disorder | 28 | 11 | 0 | |

| Parents or caregivers in prison | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Not in employment, education or training | 83 | 83 | 44 | |

| Teenage pregnancy | 100 | 100 | 33 | |

| Young carers | 50 | 44 | 22 | |

| Young offenders | 50 | 33 | 28 | |

| Adult higher risk groups | Long term physical conditions | 89 | 61 | 22 |

| Carers | 67 | 50 | 33 | |

| Post-natal depression | 28 | 17 | N/A | |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender | 33 | 22 | 28 | |

| Unemployed or benefit claimants | 72 | 67 | 56 | |

| Adults without qualifications | 56 | 56 | 17 | |

| Homeless | 89 | 72 | 33 | |

| Prisoners and offenders | 22 | 0 | 17 | |

| Refugees/ asylum seekers | 39 | 17 | 22 | |

| Dementia | 100 | 89 | 28 |

Coverage of local costs of mental disorder, public mental health expenditure and economic savings from intervention

Information on estimated local costs of different mental disorder was absent despite annual costs of mental disorder being more than £105 billion in England.2 No JSNAs provided a comprehensive break down of mental health expenditure or information about potential local economic savings from effective public mental health interventions despite mental health policy highlighting timeframes of such savings and to which areas savings were accrued.12

Estimation of unmet need

No JSNAs provided information about size or impact of mental health unmet need which limited value to inform commissioning decisions.

Analysis of rating accuracy

In order to exclude the possibility that assessment of data by the rater was inaccurate, level of agreement between two independent raters was assessed for three local authorities as outlined in Table 3. Inter-rater reliability was good with Kappa scores 0.925 for local authority A, 0.877 for local authority B and 0.825 for local authority C.

Level of agreement between two independent raters assessing the inclusion of mental health data in JSNAs of three local authorities

| . | ‘No’ response . | ‘Yes’ response . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 for local authority A | 227 | 28 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority A | 225 | 30 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority B | 196 | 59 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority B | 190 | 65 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority C | 243 | 12 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority C | 245 | 10 | 255 |

| . | ‘No’ response . | ‘Yes’ response . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 for local authority A | 227 | 28 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority A | 225 | 30 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority B | 196 | 59 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority B | 190 | 65 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority C | 243 | 12 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority C | 245 | 10 | 255 |

Level of agreement between two independent raters assessing the inclusion of mental health data in JSNAs of three local authorities

| . | ‘No’ response . | ‘Yes’ response . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 for local authority A | 227 | 28 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority A | 225 | 30 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority B | 196 | 59 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority B | 190 | 65 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority C | 243 | 12 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority C | 245 | 10 | 255 |

| . | ‘No’ response . | ‘Yes’ response . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 for local authority A | 227 | 28 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority A | 225 | 30 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority B | 196 | 59 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority B | 190 | 65 | 255 |

| Rater 1 for local authority C | 243 | 12 | 255 |

| Rater 2 for local authority C | 245 | 10 | 255 |

Discussion

Statutory guidance on JSNAs and JHWSs13 highlights the importance of JSNAs to provide information about local health and social care needs. This is a particular issue for mental health since only a minority of the quarter of England's population affected by mental disorder each year receives any treatment4,6 and far smaller proportions receive interventions to prevent mental disorder or promote mental wellbeing.10,11

Main findings of this study

This study found that mental health information within JSNAs was both difficult and time consuming to locate. Despite the high prevalence of mental disorder and low coverage of evidence based treatments, only a minority of JSNAs mentioned most mental disorders: for child and adolescent mental disorder, only drug misuse was mentioned in more than 50% of JSNAs. Although the proportion of adult mental disorders mentioned in more than 50% of JSNAs included depression (72%), psychosis (67%), dementia (100%), alcohol dependence (83%), drug dependence (78%) and suicide (100%), seven other adult mental disorders were mentioned in less than 50% of JSNAs. However, many JSNAs mentioned mental disorder only as figures in tables and did not cover in further detail in the body of the text.

The proportion of JSNAs providing local estimates of different mental disorder was lower still with less than half of JSNAs for any child and adolescent mental disorder and more than 50% of JSNAs for only six adult mental disorders (Table 1). However, local prevalence estimates were usually national rates rather than taking into account local factors. The proportion of JSNAs providing local numbers receiving treatment only occurred for child and adolescent smoking (11%), alcohol (39%) and drug misuse (50%) and six adult mental disorders.

Almost half JSNAs mentioned mental wellbeing although only 6% included local estimated levels from the annual national ONS wellbeing survey.8 If mental wellbeing promotion initiatives were mentioned, they were done so in passing with no reference to numbers receiving intervention.

Most JSNAs provided little information about impact of broader determinants on mental health required by statutory guidance13 or how poor mental health impacts on other areas. This was particularly the case for the association between mental disorder and alcohol, drug and tobacco misuse.

Groups at higher risk of mental disorder require representation in needs assessments to facilitate targeted approaches and prevent widening of inequalities although a large proportion of JSNAs did not mention such groups and the link to higher risk of mental disorder was made in less than 30% of JSNAs.

No JSNAs included local estimated costs of mental disorder, mental health expenditure or information about potential local economic savings from effective public mental health interventions despite mental health policy highlighting economic savings from such interventions.12 Furthermore, no JSNAs provided information about size of mental health unmet need.

The findings suggest that lack of appropriate mental health intelligence in JSNAs implies that local authorities and CCGs are unable to effectively carry out their statutory duties to prepare JSNAs and JHWSs.13 This intelligence gap also affects ability of local authorities to commission according to local need and may in part account for continuing low coverage of public mental health interventions.

The absence of relevant public mental health information within JSNAs can be partly explained by lack of:

Awareness about the importance and impact of mental disorder and wellbeing which has training implications about public mental health knowledge required by public health professionals

Standard template, format or mandatory data requirements which has wider implications for JSNA structure

Access to public mental health intelligence although since this audit, an online resource17 provides some of the information identified in mental health needs assessments

Training on how to integrate relevant mental health information into JSNAs

Appropriate inclusion of mental health in JSNAs enables assessment of population needs for treatment of mental disorder, prevention of mental disorder and promotion of mental wellbeing as well as the appropriate use of such information to inform strategic development, commissioning and inter-agency coordination.

Public mental health commissioning guidance9 highlights various types of mental health information required in JSNAs. The first author has further developed this guidance to provide comprehensive mental health needs assessments for local authorities in England covering more than seven million people.20 This work identified all nationally available public mental health intelligence as well as locally provided information where relevant data was not publically available. Mental health needs assessments have evolved to include the following types of public mental health intelligence required in JSNAs to assess level of public mental health need and provide costed solutions to address such need:

Levels of mental disorder and wellbeing

Levels of risk and protective factors

Proportion from different higher risk groups

Coverage and outcomes of public mental health interventions

Estimated economic costs of mental disorder to both health and other sectors

Size and cost of the gap in provision of public mental health interventions

Expenditure on different types of public mental health intervention

Estimated economic savings to different sectors from improved coverage of a range of public mental health interventions

Each mental health needs assessment includes a needs assessment for (i) mental disorder treatment by primary and secondary care as well as input from social care and third sector, (ii) mental disorder prevention and (iii) mental wellbeing promotion with particular sections more relevant to certain sectors. Such assessments have supported inclusion of mental health relevant information into JSNAs as well as inter-agency coordination, strategic development and commissioning decisions.20

What is already known on this topic

Other studies have identified that mental health coverage in JSNAs is poor. A review of child and adolescent mental health in 145 JSNAs found that two-third of JSNAs had no specific section for child and adolescent mental health while one-third of JSNAs did not include an estimated or actual level of locally required child and adolescent mental health services.21 A further regional review of JSNAs and JHWSs found limited coverage of conditions which cause considerable distress but which were not life threatening such as depression and eating disorder.18

What this study adds

This study outlines the public mental health information required as part of a JSNA and quantifies the coverage of such information in a sample of JSNAs covering 6 million people. It identifies possible reasons, implications and solutions for poor coverage of mental health in JSNAs.

Limitations of this study

This study overestimated coverage of mental health since it included JSNAs which only mentioned figures in Tables and did not cover mental health in further detail. It was carried out in October and November, 2013 and since then, coverage of mental health in JSNAs may have been affected by factors such as reducing public health budgets19 and an online mental health intelligence resource.17 It only addressed a particular part of London and adjacent areas.

Conclusion

Almost a third of UK disease burden is due to mental disorder, which affects almost a quarter of the adult population in England each year, and results in a broad range of public health relevant impacts. Despite the existence of cost effective public mental health interventions, only a minority of people with mental disorder receive any treatment while coverage of interventions to prevent associated impacts, prevent mental disorder and promote mental wellbeing is far less. This study found that mental health coverage in JSNAs is usually inadequate to assess size, impact and cost of unmet need for treatment of mental disorder, prevention of associated impacts, prevention of mental disorder or promotion of mental wellbeing. This results in local authorities and CCGs being unable to carry out their statutory duties to assess local mental health needs to inform strategic development and commissioning. It may also be an important reason for the perpetuation of the low coverage of public mental health interventions and the lack of parity between physical and mental health. Actions to increase JSNA mental health coverage would include improving public mental health knowledge through training, standardizing required mental health information, improving awareness of available online public mental health intelligence,17 training on incorporation of relevant information, and ensuring appropriate public health budgets. Associated improved coverage of public mental health interventions will result in a range of improved public health relevant outcomes and associated economic savings across different sectors.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support and advice of Professor Peter Fonagy (UCL and UCLPartners).

Conflicts of interest

Jonathan Campion: Jonathan has carried out mental health needs assessments for local authorities and mental health trusts for which his employer received payment. Claire Coombes: None declared. Neel Bhaduri: None declared.

References

Campion J (in preparation) Mental health needs assessments for seven million population in England.