-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Martina Milana, Francesco Santopaolo, Ilaria Lenci, Simona Francioso, Leonardo Baiocchi, Results of a fast-track referral system for urgent outpatient hepatology visits, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 27, Issue 2, April 2015, Pages 132–136, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In 2011, our regional district adopted an experimental system for fast referral (within 72 h) by general practitioners to several outpatient specialist evaluations including hepatology. The aim of this study was to assess the characteristics and appropriateness of urgent hepatology visits.

Retrospective study.

Hospital-based study in Italy.

A total of 192 subjects referred to our outpatient hepatology clinic classified as ‘urgent’ were compared with 397 patients evaluated with standard referral. A comparison with 200 patients visited just before the adoption of the new system was also included.

Patients’ features and appropriateness of referral in urgent and non-urgent groups using the new system.

Increase in liver enzymes was the main factor that leads to specialist hepatology consultation and was more frequent in the urgent group (37% vs. 27.1%, P < 0.001). Liver malignancies were identified in 2.6% of patients in the urgent group, whereas this percentage was 10 times lower in the non-urgent group (P = 0.01). Urgent patients required inpatient admission more frequently compared with non-urgent patients (4.2% vs. 0.5%; P = 0.003). Inappropriate referral was recorded in 41% of cases in the urgent group (no reason for urgency 27%; condition not attributable to liver 13.5%). In the non-urgent group, consultations were inappropriate in 20.1% of cases (condition not attributable to liver). In comparison with the old system, the new one allocated >85% of patients with serious illness to urgent group.

This strategy is helpful in selecting patients with more serious hepatic conditions. Appropriateness of referral represents a crucial issue.

Background

Long wait times for health care is an important issue that negatively influence patient satisfaction [1], and in some cases, the possible treatment and outcome of disease [2, 3]. In addition, data from the American Veteran service report that long wait times are associated with decreased use of health-care facilities also in subjects who are in the most need of care [4]. Unfortunately, several countries are experiencing a progressive increase in wait times for clinical procedures or specialist outpatient consultations [5].

Strategies to improve health systems in this regard are an argument of debate, and several approaches, including electronic referral, have been adopted to allow quick outpatient evaluation of more seriously ill patients [6].

In this perspective, an experimental system (named DoctorCUP) was adopted in our regional district (Rome area, Lazio Region) in June 2011 to allow a fast-track referral by general practitioners (GPs) for several procedures and specialist evaluations. The DoctorCUP system is organized to ensure specific clinical care within 72 h when an urgent referral is made by a family doctor.

The DoctorCUP fast-track strategy includes radiologic and endoscopic procedures and several specialist visits, such as cardiologic, oncologic, gynecologic and ophthalmic. Since the clinical sequence of liver diseases includes acute situations that are potentially harmful and can rapidly evolve, which leads to worse outcomes or death if diagnosis and treatment are delayed [7–10], our Liver Unit (Department of Medicine, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy) was endorsed in the experimental phase of DoctorCUP system for urgent hepatology visits.

In this article, we report the data for the first 30 months since the adoption of the fast-track referral system for urgent outpatient hepatology visits. A comparison with patients with standard (non-urgent) outpatient referral is also reported. Finally, data from the new system were compared with those of the old system.

Methods

DoctorCUP system

In the previous system, outpatient evaluations were done one after another in the order of reservation by a regional call center on the basis of a query by a family doctor. The clinical condition of the patient did not represent an element of priority. The DoctorCUP system introduced the possibility to write ‘urgent’ at the end of the request. After receiving an urgent query, the call center allocates the requests in specific slots created in the health service system to allow the specialist evaluation or procedure within 72 h. A specific phone line was active during working time for family doctors seeking assistance from the DoctorCUP system.

Patients

A total of 192 subjects were evaluated in our outpatient hepatology clinic in the fast-track regimen during the first 30 months of the adoption of the DoctorCUP system. Clinical and biochemical data, type and etiology of disease and outcome after evaluation (i.e. outpatient follow-up, sent back to general practitioner or inpatients admission) were recorded for each patient. In addition, the appropriateness of the referral was evaluated in terms of (i) significant true urgency and (ii) significant need for hepatologist consultation. The data of 397 patients coming from standard (non-urgent) outpatient referral, during the same period of time (control group), and of 200 patients referred just before the adoption of the fast-track system were also recorded. In the latter groups, appropriateness of referral was evaluated with regard to the real need for hepatologist consultation. All outpatient visits were conducted by two specialists in the field of hepatology (each with >10 years of clinical activity) within the same institution. The final decision on the appropriateness of each single referral was made by the same two physicians, who together reviewed all outpatient visits reaching a 100% agreement after consulting. During the first visit, patients underwent a complete physical examination, and the results together with the clinical history were recorded in a clinical chart that was used for further patient follow-up. All data from clinical charts were gathered and retrospectively evaluated. The study was submitted and approved by the review board of our institution.

Statistics

Data were stored and analyzed using a statistical software package (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were compared using t-test for unpaired data. The χ2 test was used to evaluate statistical significance of discrete variables. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Individual characteristics of patients

Patients evaluated as urgent in our outpatient clinic did not differ from the control group in terms of sex and age (males 57.8% vs. 55.5% not statistically significant; age 57 ± 17 vs. 56 ± 16 not statistically significant).

Moreover, there were no differences between patients evaluated with the old system and those evaluated with the new fast-track referral system (males 56.3% vs. 55.2% not statistically significant; age 56 ± 18 vs. 57 ± 14 not statistically significant).

Comparison between urgent and non-urgent patients on the basis of disease type

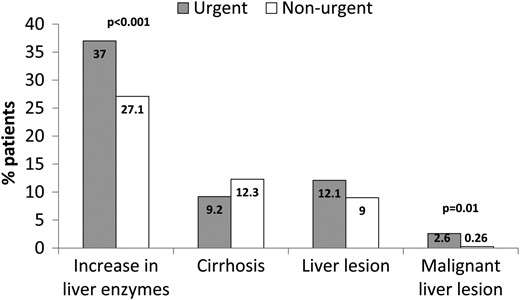

Figure 1 reports the main indications for urgent or non-urgent visits during the study. Increase in liver enzymes was the main reason that leads to specialist hepatology consultation in both groups. However, this type of abnormality was statistically more frequent in patients in the urgent group, comprising more than one-third of all general practitioner referrals. Abnormal liver enzyme levels were probably also the main factor that induce GPs to request urgent evaluation. In fact, transaminase levels were statistically higher in patients belonging to the urgent group in comparison with those in the non-urgent one (Aspartate aminotransferase times upper limit of normal 3.1 ± 4.5 vs. 1.3 ± 0.9, P < 0.001; Alanine aminotrasferase times upper limit of normal 3.8 ± 4.4 vs. 2.1 ± 1.6, P < 0.001). The percentage of patients referred to specialist visit for cirrhosis or liver lesions did not differ between groups. However, malignant lesions were identified in 2.6% of patients in the urgent group, whereas this percentage was 10 times lower (0.26%) in the non-urgent group.

Comparison between urgent and non-urgent patients according to main types of disease. Results are expressed as percentage of patients in the two groups.

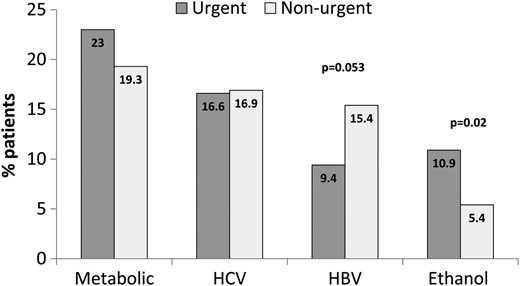

Comparison between urgent or non-urgent patients according to main etiology of liver disease

Main etiologies of liver disease in urgent and non-urgent patients are reported in Figure 2. Metabolic liver disease was the leading etiology (nearly 20%) diagnosed in both groups. This was followed by Hepatitis C virus (HCV), accounting for 16% of cases, with minor differences between urgent and non-urgent patients. Liver conditions attributable to hepatitis B virus (HBV) were more frequent in the non-urgent group with a difference close to statistical significance (P = 0.053). Finally, ethanol-related liver disease was statistically more frequent in patients referred for urgent visits in comparison with others (P = 0.02).

Comparison between urgent and non-urgent patients according to main etiologies of liver disease. Results are expressed as percentage of patients in the two groups.

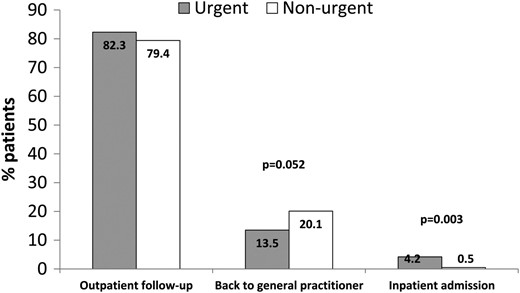

Comparison between urgent and non-urgent patients according to outcomes

Patient outcomes, categorized as follows: (i) outpatient follow-up, (ii) referred back to general practitioner and (iii) inpatient admission, are shown in Figure 3. The majority of patients in both groups (nearly 80%) were scheduled for an outpatient follow-up. One-fifth of non-urgent patients were referred back to the general practitioner without further specialist evaluation. The percentage of these patients was higher in the non-urgent group than in urgent group, approaching statistical significance (20.1% vs. 13.5%, P = 0.052). Finally, 4.2% of urgent patients required prompt inpatient admission after specialist evaluation, whereas this occurred only for 0.5% of patients in the non-urgent group (P = 0.003).

Comparison between urgent and non-urgent patients according to the outcome after the first visit. Results are expressed as percentage of patients in the two groups.

Appropriateness of referral in urgent and non-urgent patients

As specified in Methods, appropriateness of urgent referrals was evaluated in terms of (i) significant urgency and (ii) significant need for specialist hepatology consultation. Non-urgent referrals were evaluated according to point (ii) only (Table 1). Referrals were considered inappropriate in 41% of cases in the urgent group. In 27.1% of these cases, referral was considered inappropriate in terms of its urgency, as the patients had stable liver disease that did not require prompt evaluation and relevant diagnostic or therapeutic changes. In the remaining 13.9%, the indication for consultation was not hepatology. In the non-urgent group, consultations were inappropriate in 20.1% of cases. The comparison between the two groups in terms of inappropriateness of referral for specialist hepatology consultation showed that inappropriate visits for patients lacking symptoms or signs suggestive of liver disease were statistically more frequent in the urgent group than in the non-urgent group (53.8% vs. 27.4%; P = 0.02). On the other hand, the main reason for inappropriateness in non-urgent visits was positivity to routine biochemical viral markers of hepatitis (hepatitis A virus (HAV) and HBV) indicating healing from infection with normal liver function tests (33.2% vs. 7.6%, P = 0.01). Incidence of other reasons for inappropriateness did not differ between the two groups, whereas steatosis with normal test results (7.8%) and referrals with undefined indication (6%) were a significant cause of inappropriate visits in the non-urgent group only (Table 1).

Appropriateness of referral in urgent and non-urgent groups

| Urgent visits lacking appropriateness (78; 41% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness for urgent referrals (patients n = 52) | % |

| Stable liver disease not requiring prompt diagnostic or therapeutic measures | 100 |

| Reasons for inappropriateness with regard to real need for specialist consultation (patients n = 26) | |

| Symptoms or sign not suggestive of liver disease | 53.8a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 31 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 7.6 |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 7.6b |

| Non-urgent visits lacking appropriateness (80; 20.1% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness regarding real need for specialist consultation | % |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 33.2b |

| Symptoms or signs not suggestive of liver disease | 27.4a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 21.6 |

| Steatosis with normal liver function | 7.8 |

| Indication undefined | 6 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 4 |

| Urgent visits lacking appropriateness (78; 41% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness for urgent referrals (patients n = 52) | % |

| Stable liver disease not requiring prompt diagnostic or therapeutic measures | 100 |

| Reasons for inappropriateness with regard to real need for specialist consultation (patients n = 26) | |

| Symptoms or sign not suggestive of liver disease | 53.8a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 31 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 7.6 |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 7.6b |

| Non-urgent visits lacking appropriateness (80; 20.1% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness regarding real need for specialist consultation | % |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 33.2b |

| Symptoms or signs not suggestive of liver disease | 27.4a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 21.6 |

| Steatosis with normal liver function | 7.8 |

| Indication undefined | 6 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 4 |

Results are expressed as percentages.

aStatistically significant difference (P = 0.02).

bStatistically significant difference (P = 0.01).

Appropriateness of referral in urgent and non-urgent groups

| Urgent visits lacking appropriateness (78; 41% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness for urgent referrals (patients n = 52) | % |

| Stable liver disease not requiring prompt diagnostic or therapeutic measures | 100 |

| Reasons for inappropriateness with regard to real need for specialist consultation (patients n = 26) | |

| Symptoms or sign not suggestive of liver disease | 53.8a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 31 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 7.6 |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 7.6b |

| Non-urgent visits lacking appropriateness (80; 20.1% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness regarding real need for specialist consultation | % |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 33.2b |

| Symptoms or signs not suggestive of liver disease | 27.4a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 21.6 |

| Steatosis with normal liver function | 7.8 |

| Indication undefined | 6 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 4 |

| Urgent visits lacking appropriateness (78; 41% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness for urgent referrals (patients n = 52) | % |

| Stable liver disease not requiring prompt diagnostic or therapeutic measures | 100 |

| Reasons for inappropriateness with regard to real need for specialist consultation (patients n = 26) | |

| Symptoms or sign not suggestive of liver disease | 53.8a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 31 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 7.6 |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 7.6b |

| Non-urgent visits lacking appropriateness (80; 20.1% of the total) | |

| Reasons for inappropriateness regarding real need for specialist consultation | % |

| Viral markers clearly suggesting healing from infection with normal liver function tests | 33.2b |

| Symptoms or signs not suggestive of liver disease | 27.4a |

| Liver lesion of clearly benign origin | 21.6 |

| Steatosis with normal liver function | 7.8 |

| Indication undefined | 6 |

| Condition requiring surgery | 4 |

Results are expressed as percentages.

aStatistically significant difference (P = 0.02).

bStatistically significant difference (P = 0.01).

Comparison between the old and the new referral systems

The comparison between the 200 visits referred just before the adoption of the fast-track system and all visits referred with the new system (n = 589) showed no statistical difference in terms of incidence of liver malignancies or relevant disease requiring prompt inpatient admission (liver malignancies incidence 0.5% vs. 1%; old system vs. new system; inpatient admission 0.5% vs. 1.5%; old system vs. new system). Also, appropriateness of referral with regard to significant need for specialist hepatology consultation was unchanged (18.5% vs. 18%; old system vs. new system). However, with the new system, 86% of liver malignancies and 89% of severe disease requiring prompt hospitalization were correctly allocated in the urgent referral group.

Discussion

Currently, there is a growing interest in medical policy research that aims to improve the health-care delivery system using an evidence-based or framework approach [11, 12]. In the field of digestive diseases, the majority of these studies focus on endoscopy in both the outpatient and inpatient settings [13–16].

Liver pathologies, however, are an important cause of morbidity worldwide [17, 18] with an estimated mortality of 170 000 per year in Europe [18]. Despite this, recent data from the USA suggest suboptimal care delivery in patients with these pathologies [19]. Access to hepatology care, including liver transplantation, seems, in fact, unequal, as it is affected by individual and organizing factors, thus strongly advocating the necessity for different care delivery strategies. In addition, health-care system resources are limited, determining, for instance, an increase in waiting times for specialist evaluation in several countries, and thus posing the problem of the timely evaluation of more seriously ill patients [5, 19, 20].

The experimental adoption, for hepatology, of ‘preconsultation exchange’ (answering a clinical question posed by a referring physician without a formal patient visit and after a specific written query) was examined in a study by Sewell et al. leading to the following results: (i) queries were appropriate in 14% of cases only, and (ii) the remaining queries were either inappropriate or not sufficiently detailed [21]. These data underscore the importance to improve education and communication tools of primary care provider. In our study, we present the results of a strategy to reduce waiting times for specialist hepatology evaluation based on urgent referral (within 72 h) by GPs.

Our results show that the main cause for referral to a specialist hepatology visit in our geographic area is the increase in liver function test levels. When faced with this clinical condition, GPs are generally more prone to refer patients as urgent. The decision of the referring physician on the urgency of the patient is clearly determined by the degree of biochemical alterations; a mean level of transaminases >3 times the upper limit of normal is statistically associated with referral of patients as urgent.

Another difference is found with regard to malignant liver lesions. The frequency was 10 times higher in the urgent group than in the non-urgent group. In comparison with the old referral system, in which the possibility to schedule a patient according to his clinical priority was not present, the new system allowed the allocation of malignant liver tumors as urgent in 86% of cases. The latter findings are encouraging, as the prompt evaluation of patients with primary liver malignancy may allow possible curative measures, as demonstrated by data from patients under surveillance for this neoplasm [22]. There were no major differences in referral for other indications, such as liver cirrhosis, between the urgent and non-urgent groups.

With regard to etiology, metabolic liver disease and HCV were the most frequent in both groups and with similar percentages. These results are in agreement with the data recently reported by studies conducted in Italy [23, 24]. A statistically significant increase in referrals for alcoholic hepatitis was observed in the urgent group. The reasons for this finding are unclear; it could be, however, that GPs feel that this type of patient may benefit from prompt referral to a multidisciplinary (medical, psychological, nutritional) hospital-based program.

With regard to outcome after the first visit, prompt inpatient admission was scheduled eight times more frequently in the urgent rather than in the non-urgent group, supporting the utility of the fast-track strategy in selecting more seriously ill patients. Again, as improvement in comparison with the old referral system, the fast-track strategy allocated the more seriously ill patients as urgent in 89% of cases. Appropriateness of referral to hepatology represented an important issue in our study, as also observed in a previously mentioned study, conducted in a different geographic area and based on preconsultation exchange strategy [21].

The reasons, however, varied in frequency between the urgent and non-urgent groups. General practitioners often refer patients with symptoms mistakenly attributed to the liver, and this occurrence was more commonly recorded in subjects belonging to the urgent group (P = 0.02). On the other hand, several non-urgent patients were referred for consultation for viral markers (HAV or HBV) suggesting healing from infection without relevant consequences. The latter findings indicate the need for the implementation of an educational hepatology program for GPs. Other studies conducted also in Italy have already evidenced the need for training programs in chronic hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatocellular carcinoma [23, 25–27]. On the other hand, the assessment of current educational strategies on metabolic liver disease indicates a number of limits, thus opening a debate on appropriate educational methodologies [25, 28]. For instance, education based on guidelines is flawed by factors such as year of publication, geographical area, epidemiology and inconsistencies among the various issues. As a result, there have been suggestions for the creation of a global document in order to overcome fragmentation, heterogeneity and apparent contradictions [28].

On the other hand, the adoption of a specific educational program on NASH for GPs did not give completely satisfactory results [25]. In fact, knowledge on the issue, evaluated by a questionnaire, improved by a rate of nearly 80%, but changes in practice habits accounted for not >30%. In addition, the authors evidenced a possible problem in knowledge retention in the long term. On this basis, a lifelong learning program should be hypothesized also to match clinical practice with more recent medical advances.

In conclusion, our study shows that patients evaluated through a fast-track referral system for urgent hepatology visits had a 10 times greater incidence of primary liver neoplasms and 8 times greater incidence of serious conditions requiring prompt hospitalization. As improvement with a referral system in which outpatient evaluations are done one after another in the order of reservation and in disregard of the clinical condition of the patient (our old system), >85% of patients with serious diseases are allocated in the urgent group by referring physicians. Appropriateness of referral represents an important issue suggesting the need for educational programs in hepatology for GPs.

Funding

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Serena Rotunno and Heather Francis for grammatical revision of the content.