-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gary E. Hollibaugh, The Incompetence Trap: The (Conditional) Irrelevance of Agency Expertise, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1 April 2017, Pages 217–235, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw066

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Formal models of the appointments process typically cast the decision of the appointing executive as one where an open position is assumed and an appointee is chosen in order to maximize the utility of the executive (and perhaps that of the legislature if confirmation is required). However, several—often patronage-focused—processes within the appointments process focus instead on finding acceptable positions for “necessary-to-place” individuals. Here, I develop a model where the goal is to find the best position for such an individual. In contrast to many existing models of the appointments process, I find that when the personnel process is focused on finding the best position for a given person as opposed to finding the best person for a given position, “turkey farms”—agencies that have high numbers of minimally-competent (but necessary-to-place) individuals among their ranks—can result in equilibrium. Moreover, once agency capacity is sufficiently low, incompetent individual appointees no longer have detrimental effects on the utilities of the appointing principals, which further incentivizes the usage of certain agencies as “turkey farms.”

Introduction

“[Immediately after the 1988 election], George W. Bush was the chair of something called the Silent Committee which was put together of people who… had been in the Bush world for a number of years and knew the other people who have been in the Bush world. The whole idea of that exercise was to put together the list of the absolutely deserving, those who if they wanted an appointment or some other consideration…would get it. They were the ones to be taken care of.”

—Chase Untermeyer, Former Director of the Office of Presidential Personnel1

On November 6, 2008, just two short days after then-Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) was elected the 44th President of the United States, the Web site of the incoming Obama Administration’s transition team—the Obama–Biden Transition Project—went live at http://www.change.gov.2 On the Web site there was a link to apply for non-career jobs within the incoming administration; whereas the initial online screening process was brief, applicants were asked several days after completing the initial screening process to complete a 63-item questionnaire.3 Within a month, over 300,000 individuals had submitted online applications for about 3,300 politically-appointed positions.4 Other recent administrations were faced with numbers of resumes that were orders of magnitude larger than the overall numbers of politically-appointed positions, though nowhere near the numbers faced by the Obama administration; this might has been due to the well-publicized and online nature of the Obama application procedure, as well as a possible secular increase over time. That said, in a series of recommendations to future transition teams, Johnson (2008) suggested that the 2008 transition team should expect “at least 40,000 [job seekers] in the first few weeks and at least 75,000 in the first few months” (p. 625). Citing Clinton-era officials, Lewis (2008) provided similar figures, with “[o]ne former Clinton personnel official estimat[ing] that they received 50,000 resumes in the first week of the administration,” with the Clinton administration receiving over 100,000 resumes overall (p. 28).

Though it should come as no surprise, not all job-seekers are treated the same way. Some possess experience and/or expertise that make them particularly well-suited for policymaking positions, and others may have “connection[s] to the campaign, to the party, interest groups, or patrons in Congress important to the administration” (Lewis 2008, p. 28); many have both. For example, Rottinghaus and Bergan (2011) and Rottinghaus and Nicholson (2010) note the importance and frequency of Congressional requests to the President for appointments of constituents and other influential individuals. More generally, executives may use appointments to enhance their standing among key electoral blocs, though they should remain aware of how such appointments may be perceived by the public (Hollibaugh 2016a; Hollibaugh 2016b).5,6

The personnel process within presidential administrations and transition teams highlight this (somewhat artificial) “formal division between patronage and policy efforts,” with the division having become more institutionalized over time (Lewis 2008, p. 64). Though historically dominated by party organizations, interest groups, key members of Congress, and incoming cabinet secretaries themselves, the rise of candidate-centered campaigns and the recent reduction of party influence in the presidential nominating process (Wattenberg 1991; but see Cohen et al. 2009) have given presidential administrations more freedom in their personnel selection strategies (Weko 1995). This has resulted in a centralization of the personnel selection process within the transition teams and the incoming administration, and the aforementioned formal division between screening for policy expertise and screening for political usefulness. Indeed, “one process revolves primarily around filling positions, and the other process revolves primarily around placing persons” (Lewis 2008, p. 30), though it should be emphasized that the distinction is one of relative importance between the two factors, and not the complete absence of one or the other. The latter process is well-described by George T. Bell, former special assistant to President Nixon; he noted that applicants who passed security checks were placed into one of several categories, ranging from “failure to appoint would result in adverse political consequences to the administration,” “played a prominent role in the campaign; recommended in the highest terms by a member of the House or Senate leadership,” “no political importance to the administration,” and “applicant not compatible with the Nixon administration and should not be appointed to public office,” among others (as quoted in Tolchin and Tolchin [2010], p. 152). Similar systems were used by Nixon’s successors, as well as his predecessors.

That the patronage process is so person-centered, and that there exist two distinct processes for filling appointed positions, both with distinct foci—one primarily on policy, and the other primarily on personnel and politics—should be reflected in how scholars theorize about the appointments process. However, data limitations arguably limit the scopes of many analyses, as scholars are more certain about the positions that must be filled than about the individuals who must be placed. Therefore, it is understandable that much of the empirical research to date on the appointments process (for both executive and judicial positions) has taken a vacancy- and/or position-centric approach (e.g., Asmussen 2011; Binder and Maltzman 2002; Hollibaugh 2015b; Hollibaugh and Rothenberg 2016; McCarty and Razaghian 1999; Ostrander 2016; Primo, Binder, and Maltzman 2008; Shipan, Allen, and Bargen 2014; Shipan and Shannon 2003). Formal approaches, however, are not necessarily subject to the same data limitations as empirical research. Yet many, if not most, formal models of the appointments process start with the premise that there exists a position that needs to be filled, and the relevant political principals can maximize their (expected) utility functions by selecting the “best” individual for this predetermined position (e.g., Bertelli and Feldmann 2007; Bonica, Chen, and Johnson 2015; Chiou and Rothenberg 2014; Gailmard 2002; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh 2015c; Jo 2016; Jo, Primo, and Sekiya 2016; Jo and Rothenberg 2012; McCarty 2004).

Since the vast majority of vacancies are filled via the policy-focused process of the Office of Presidential Personnel, this distribution of scholarly effort makes sense to some extent. However, it also overlooks the role patronage concerns play in the process; to the extent they are considered, the most common modeling frameworks tend to much more closely mirror that of the policy-driven process mentioned above, with patronage included as a source of additive utility as opposed to being drawn from an entirely different appointments process (e.g., Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh 2015c; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014). Therefore, in this article I analyze a formal model where a potential appointee is taken as given, and the executive branch is tasked with deciding into which type of position—if any—the individual should be placed. This modeling setup, although arguably a better match to the patronage-focused selection strategy, has yet to be seriously considered in formal models. Analyzing this model indicates that when the focus is on finding the optimal position for a particular person—as opposed to finding the optimal person for a particular position—agency competence can be negatively affected—even in the absence of explicit patronage utility per se—and “turkey farms” are likely to arise.7 This is in stark contrast to other position-oriented models that find that a premium is placed on agency competence, though some allow agency competence to be correlated with appointee type (Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh 2015c; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Jo and Rothenberg 2012). Moreover, I also show that once agency capacity is sufficiently low, incompetent individual appointees no longer have detrimental effects on the utilities of the appointing principals, which further incentivizes (or, perhaps, fails to disincentivize) the usage of certain agencies as “turkey farms.”

Interestingly, this person-centered (and, by implication, process-centered) explanation contrasts with previous explanations for why certain agencies are targeted as “turkey farms,” a point on which the literature has proffered multiple explanations. For example, Lewis (2008; 2009) argues that patronage appointees are easiest to place in agencies that share the president’s view about policy; this is because what experience potential patronage appointees do have “is for the party or one of the party’s core constituencies” and they want jobs that will “advance their career prospects…within the party or its constellation of related groups” (Lewis 2009, p. 65). Conversely, he argues that the most qualified appointees are placed in agencies that do not share the president’s views, in an effort to gain control of them. Additionally, while Parsneau (2013) argues that presidents place more loyalists and fewer experts in agencies high on the executive agenda, because they seek to politicize those departments and agencies most important to their agendas, Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis (2014) argue the opposite and suggest that patronage appointments are more likely to be to agencies viewed as low-priority by the President, since management and/or policy expertise in these areas are viewed as less central to the president’s policy goals. Not incidentally, former members of the Office of Presidential Personnel (OPP)—those directly involved in choosing which appointees get placed in which positions—have argued that patronage appointments tend to be to positions that are less important and have less effect on policy outcomes.8

The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), long viewed as the archetypal “turkey farm” (Lewis 2008; Wamsley and Schroeder 1996), has long had the unfortunate distinction of being viewed as unimportant and inconsequential to policy outcomes. As Wamsley and Schroeder (1996) note, from the time of its establishment until the early 1990s, it “was never a matter of partisan campaign contention and thus never on a president’s domestic agenda,” was “seen as an insignificant player in a high-stakes [national security] game,” and had policy concerns “that were post-Armageddon in nature so there was little desire to think about [them]” (p. 242). These characteristics are consistent with existing explanations for why certain agencies are targeted for less-competent patronage appointments (in particular, not being on the president’s agenda and not seen as important), and therefore become “turkey farms.” However, another possible—perhaps complementary—explanation might have been its “‘Mr. Bumble’ image [and its] reputation for petty sleaze and tacky scandals” (Wamsley and Schroeder 1996, p. 239). As I suggest herein, this reputation for subpar performance might itself be one (though by no means the only) reason for why FEMA was used as a “turkey farm”—indeed, it is certainly conceivable that the perception of subpar agency performance might have led political principals to conclude that reducing agency competence even more might not radically affect outcomes, or even that less-competent appointees might still improve peformance for ill-performing agencies. If so, then this suggests that some agencies might be more vulnerable to becoming—or remaining—“turkey farms” than others, irrespective of how they fit into the current president’s agenda or the distribution of the pool of patronage appointees.

The model in the next section analyzes this possibility explicitly. It characterizes a situation in which an executive (perhaps in conjunction with the legislature) is searching for a position for what Mr. Untermeyer referred to in the opening epigraph as an “absolutely deserving” individual. Operating under the substantive presumption that the process should—for the “absolutely deserving”—be based on the principle that, in some cases, the personnel process should focus on finding the best jobs for given individuals (and at other times finding the best individuals for given jobs), the model makes no technical assumptions about the policy priorities of the executive or the pool of patronage appointees. This is so I can focus on how a person-centered—as opposed to position-centered—appointments process might potentially result in the development of “turkey farms” and trap certain agencies in a cycle of incompetence.

Finding Jobs for the “Absolutely Deserving”: A Person-Centered Model of Agency Appointments

To analyze appointments patterns induced by a person-centered appointments process, I propose a formal model in the vein of others used to analyze other aspects of bureaucratic appointments and delegation (e.g., Bendor and Meirowitz 2004; Gailmard 2002; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh 2015c; McCarty 2004; Volden 2002), many of which are based on the seminal agenda-setter model of Romer and Rosenthal (1978) and the underlying logic of Epstein and O’Halloran (1999). However, in contrast to many existing models of appointments, I take the individual as given and optimize the principals’ utility over the best appointment type—either a unilateral appointment or a legislatively-confirmed appointment. In the United States, roughly two-thirds of all appointments are made in the first fashion, as are the vast majority of patronage appointments (Lewis 2008; Lewis 2009).9,10

The model consists of three players—the Executive, the Legislature, and the Agency. All players are assumed to have quadratic preferences over policy outcomes on a single dimension, represented as for all and . I assume decisions are delegated to agencies because of their superior information and expertise regarding policy decisions and consequences. Formally, the outcome is where is the policy chosen by the agency and —where —represents factors unobserved when statutes are written and agency staffers are chosen, but observed by the agency before policy implementation.11 Similar to other models of the appointments process (e.g., Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh 2015c; Huber and McCarty 2004), Ω roughly corresponds to the benefits of agency expertise in a particular policy area. When Ω is low, then the executive and the legislature are relatively certain about the extent to which the state of the world might change in the future, and the benefits of agency expertise are correspondingly reduced. Conversely, when Ω is high, then the executive and the legislature are uncertain about what the future might hold, and will therefore lean more upon the expertise of the targeted agency to formulate and target policy implementation to the situation of the day.12

However, in line with Hollibaugh (2015a; 2015c), as well as the “informationally imperfect” agent variation of Bendor and Meirowitz (2004), I relax the assumption that agencies can discern the true value of without error.13 Rather, agencies observe the signal with a certain amount of noise, the amount of which is inversely proportional to an agency’s competence Formally, I assume that after is chosen by Nature, the observed signal, is drawn from a distribution.14,15 After observing the agency forms its expectations of the true value of conditioning on its observation of and its own competence These are given in Lemma 1, the proof of which is in the Supplementary Appendix, and diagrams illustrating how the agency both observes signals and develops its expectations of the true state of the world are presented in figures 1 and 2.16,17

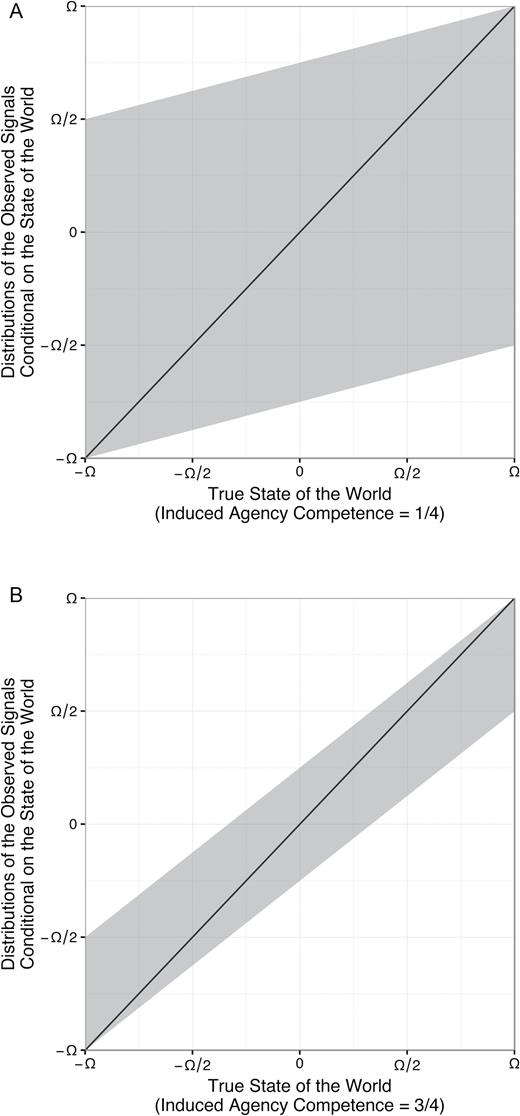

The Shaded Areas Indicate the Distributions From Which May be Drawn, Given , , and . The Solid Lines Denote . (A) Low Agency Competence; (B) High Agency Competence.

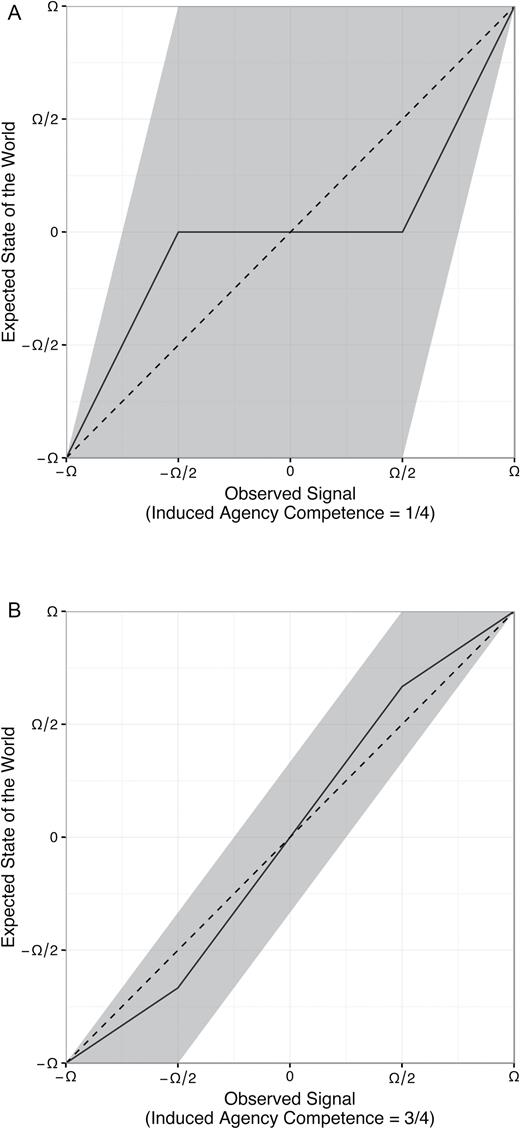

The Solid Black Lines Denote the Agency’s Expected Value of Conditional on and . The Shaded Areas Indicate the Induced Distributions From Which the Agency Believes was Drawn. The Dashed Lines Indicate . (A) Low Agency Competence; (B) High Agency Competence.

Lemma 1 Conditional on the observed value the agency’s expectation of the true value of is given by

Figure 1 showcases how the distribution of is affected by changes in Notably, as increases, the range of values can attain becomes smaller and tighter around Lemma 1 and figure 2 showcase how the agency adjusts its expectations of based on and the other relevant parameters of the model.18 Indeed, as agency competence increases, there exists less uncertainty in the distributions from which the agency believes was drawn, and it therefore places more weight on the signal due to its greater ability to disentangle the signal from the noise. When agency competence is sufficiently high and the signal is not sufficiently extreme, as is the case when then the agency’s internal correction to the signal is minor, and it simply allows for the possibility that the signal is more extreme than what was actually observed, while simultaneously discounting the possibility that the signal is sufficiently close to either or In these cases, the expected state of the world is and this situation corresponds to observed signals between and in figure 2B. Conversely, when the signal is sufficiently moderate and agency competence is sufficiently low (i.e., per the fourth condition in Lemma 1), the agency places no weight on the signal—as it is not sufficiently informative given agency competence—and the expected state of the world therefore remains This situation corresponds to observed signals between and in figure 2A.

Finally, when the signal is sufficiently extreme (i.e., which corresponds to the second and third conditions in Lemma 1), the agency is always able to learn something about the state of the world, regardless of its level of competence. This is because extreme signals rule out true states of the world at the opposite end of the distribution.19 These dynamics can be observed in both panes of figure 2, when the observed signal is not in the range. Outside this range, the height of the distributions decreases as the observed values become more extreme, thus implying that the agencies are more certain about the possible states of the world, regardless of their own levels of competence.

Notably, I do not allow for nonpolicy patronage benefits. This might seem like a strange omission, since patronage appointments “provide a means for presidents to hold supporters in line…and accomplish their policy goals” (Lewis 2008, p. 208), and that agencies run by appointees with connections to the president’s party or campaign tend to perform worse than agencies run by careerists and nonpolitical appointees, suggesting patronage is one possible method by which bureaucratic incompetence arises (Gallo and Lewis 2012; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Hollibaugh 2015a; Lewis 2007).20 Moreover, the person-centered (as opposed to position-centered) appointments process modeled here is more consistent with those used to place individuals for patronage-related purposes. However, this implies that some baseline level of patronage utility should be assumed (which therefore mitigates the rationale for explicit inclusion). Additionally, several previous models of the appointments process have induced lower levels of competence either via additive patronage utility (Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Hollibaugh 2015a), variance in how much the appointing principals value policy utility (Jo and Rothenberg 2012), or constraints placed on the pool of potential appointees (Hollibaugh 2015c).21 By eliminating these as possible sources of incompetence, making the sole departure from most existing models the focus on a person-centered appointments process, I likely bias my results in favor of not finding reductions in agency competence in equilibrium. Therefore, any decreases in equilibrium competence will be solely due to differences in the underlying process, and explicit inclusion of patronage utility would—assuming a negative correlation between patronage utility and individual competence, which is consistent with existing models—merely exacerbate the effects.

Finally, for tiebreaking purposes, I assume the legislature will reject an executive’s proposal (assuming one is put forth) if and only if acceptance would make the legislature strictly worse off versus the status quo; in other words, if the legislature is indifferent between confirmation and rejection, confirmation always results. I further assume that if the executive is indifferent between making an appointment and maintaining the status quo, she will make an appointment. Additionally, I assume that if the executive is indifferent between making a unilateral appointment and making a nomination, she will make a unilateral appointment.

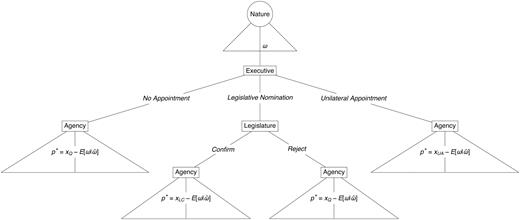

The game proceeds according to figure 3. At the outset of the game, Nature draws ω (which is unobserved by the executive and the legislature), and the executive is then tasked with (potentially) making an appointment for an individual under consideration. The executive is able to choose which kind of appointment to make—she can choose to make a unilateral appointment, or she can choose to send a nomination to the legislature—if one is to be made at all. The individual, if successfully appointed, induces an ex post agency ideal point and an ex post level of agency competence If the individual is not appointed, then the status quo agency stays in effect. After the ex post agency ideal point and competence are determined—or it is determined that the individual will not be appointed and the status quo is to remain in effect—the agency observes updates accordingly, and implements its optimal policy. Payoffs are then allocated to all players.

Importantly, when the executive is afforded the opportunity to choose between unilateral appointments or nominations subject to legislative confirmation, allowances must be made to account for the fact that positions that require legislative confirmation are qualitatively different from those that do not. Indeed, the former are more likely to impact agency outputs in tangible ways. As Lewis (2009) notes, Schedule C positions, which are subject to direct executive appointment and are typically used to satisfy patronage demands, “receive lower pay and tend not to have managerial responsibilities” (p. 67); other types of unilaterally-appointed positions may be treated analogously. Because of this, I assume that if is the induced agency competence after a legislatively-confirmed nominee, and if is the status quo level of agency competence, then is the induced agency competence after a unilaterally-appointed appointee, where is the ability of a unilaterally-appointed appointee to affect agency outcomes relative to that of a legislatively-confirmed one. Similarly, is the induced agency ideal point after a unilaterally-appointed appointee, where is the induced agency ideology after a legislatively-confirmed appointee.22,23

Given the structure of the game and these additional assumptions, the expected utility functions for the executive are as follows:

Similarly, the legislature’s expected utility functions are

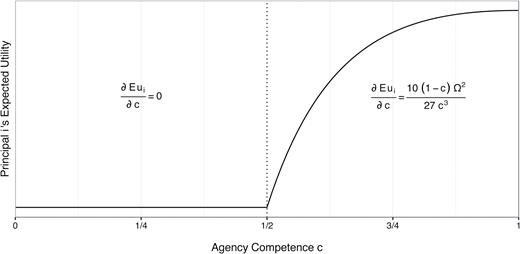

Before solving for the equilibrium outcomes of the game, I first take the derivatives of the aforementioned expected utility functions of the principals with respect to and plot the relationship between and the expected utilities in figure 4. Although the results for are obvious from inspection of the expected utility functions, the results for are not necessarily so. Unsurprisingly, when the derivative is positive with respect to indicating a positive relationship between agency competence and the principals’ expected utilities. However, note that the expected utility function is concave, indicating decreasing marginal returns to increased agency competence. This relationship suggests that, in substantive terms, there is little practical difference between having an agency operate at maximal competence versus one with reasonably high—but not maximal—competence. Moreover, unless agency competence is sufficiently high it does not enter into the utility equations of the principals. Proposition 1 is therefore derived.

Proposition 1 Ceteris paribus, when agency competence is sufficiently low, neither decreases in agency competence, nor sufficiently small increases in the same, will affect the principals’ utility functions.

One implication of Proposition 1 is that, once the competence of a particular agency becomes sufficiently low, principals will suffer no disutility from using that agency as a “turkey farm.” However, it should be reiterated that this result is consistent with other models of the appointment process that include agent/agency competence as a parameter, in that the principals’ utilities are strictly (weakly) increasing in agency competence when thus implying Corollary 1. For example, Hollibaugh (2015a; 2015c) and Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis (2014) present models where the agency’s signal about the state of the world is a binary variable, and its competence reflects the likelihood of observation (with the implicit assumption that “observation” is tantamount to correct observation). In these models, agency incompetence reduces the principals’ utilities by inducing uncertainty about the eventual policy outcome. Here, using a different mechanism for agency competence—in that higher levels of agency competence reduce noise, as opposed to higher levels increasing the probability of observation—I find a similar result, though my approach also allows one to derive the conclusion about competence not mattering once .24,25

Corollary 1 Ceteris paribus, increases in agency competence always weakly increase the principals’ expected utility.

As the informed player moves last, I employ the sequential equilibrium solution concept and solve the game via backwards induction (Kreps and Wilson 1982). After observing the agency sets a policy which it chooses in order to maximize Clearly, the agency will set Given that is a function of and the executive must take this into account and determine not only her own expected utilities and optimal action accordingly, but also what the legislature will do if a nomination is made.26 Given these utility functions, equilibrium decisions of both the legislature and the executive are respectively presented in Lemmata 2 and 3.

Lemma 2 The legislature will confirm a nomination of if and will reject otherwise.

Lemma 3 The executive’s equilibrium strategies are given by

That is, the executive will make a nomination if confirmation by the legislature will be forthcoming, if the nomination leads to strictly higher utility to the executive than the status quo, and if the nomination leaves the executive strictly better off than a unilateral appointment. The executive will make a unilateral appointment if doing so is weakly preferred to the status quo, and if (a) a unilateral nomination is weakly preferable to a legislatively-confirmed nomination (regardless of the expected actions of the legislature), or if (b) the legislature will not confirm a nomination. In all other cases, the executive will take no action and no appointment of either type will be made.

However, although the equilibrium appointment outcome is of some interest here, it is arguably of less interest than it is in other models of the appointments process. Rather, since the model here frames the candidate as given, and simply asks the executive to determine whether or not to place the individual in a position—and if so, which position—this model arguably provides a closer match for the task of finding the correct position for someone who needs to be placed (e.g., for patronage-related reasons). Therefore, it is especially instructive in this case to simply examine the conditions under which an individual will be placed in any job. Lemma 4 and Proposition 2 provide formal conditions under which an appointment of any type will be made.

Lemma 4 An appointment of some type will be made if

or if

Proposition 2 If the status quo level of agency competence is sufficiently low and the potential appointee—if successfully appointed—will not move agency policy further away from the executive, then an appointment of some type is guaranteed, regardless of the resulting level of induced agency competence.

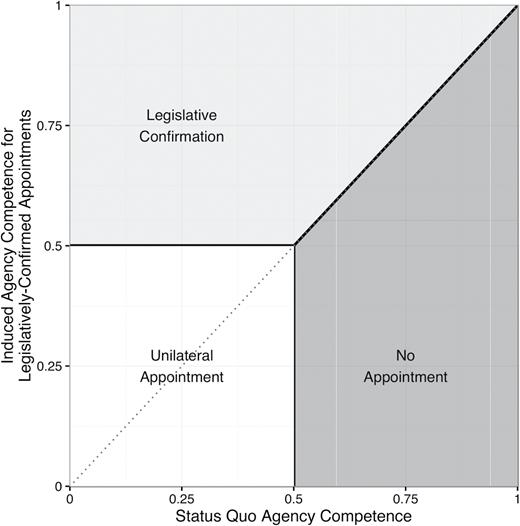

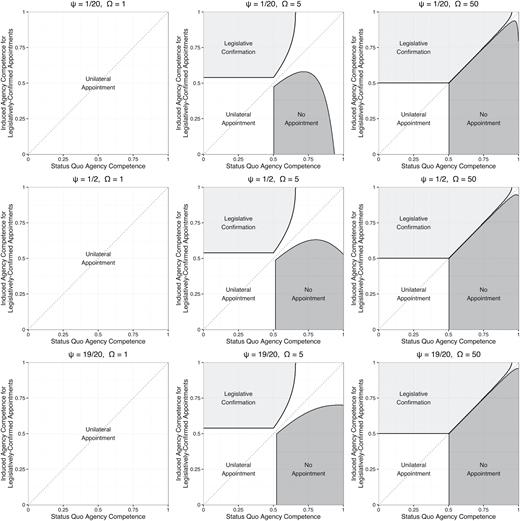

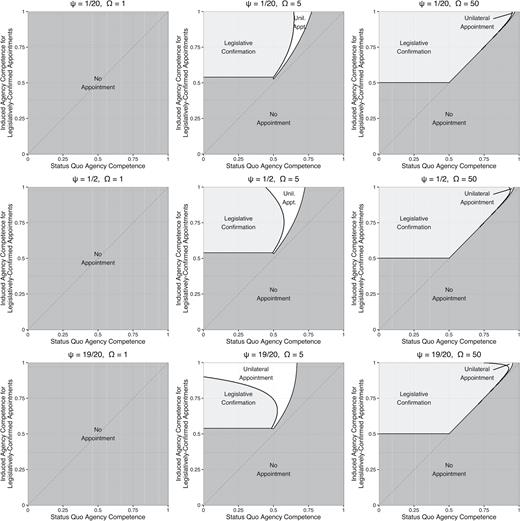

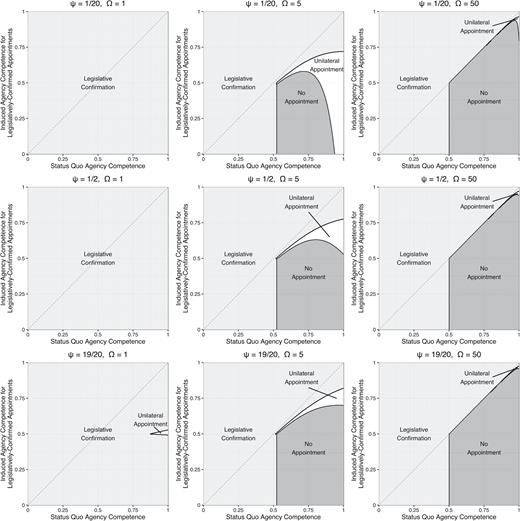

To aid in substantive interpretation, figures 5 through 8 present equilibrium outcome types for a variety of parameter settings; in all panels, the status quo is equidistant from both the executive and the legislature.27 In all four figures, the 45° diagonal line separates regions where induced agency competence will be increased (above the line) from those where the appointment will reduce it (below the line).28

Equilibrium Appointment Types—Induced Agency Ideal Point Unchanged.

Equilibrium Appointment Types—Induced Agency Ideal Point Closer to Executive and Farther from Legislature.

Equilibrium Appointment Types—Induced Agency Ideal Point Farther From Executive and Closer to Legislature.

Equilibrium Appointment Types—Induced Agency Ideal Point Closer to Both Executive and Legislature.

Substantively speaking, Proposition 2 suggests that if the executive has to place into a government position an individual with whom she is ideologically compatible (in that she will not move agency policy further away from the executive), and the individual in question is lacking in relevant technical expertise, then—if nothing else—a position in a sufficiently underperforming agency will be preferable to the status quo, even if it further reduces agency capacity. Importantly, these results assume zero patronage utility will be derived from such an appointment; increasing patronage utility will simply make appointments weakly more appealing in all cases.

The effects of the benefits of agency expertise () and the relative level of influence within the agency () are quite straightforward when the appointee will not affect the relative ideological balance between the executive and the legislature (i.e., ), regardless of the type of position into which she may be placed. These dynamics are displayed in figure 5. That figure 5 contains only one pane, as opposed to the multi-pane figures 6 through 8, indicates that when the status quo will be unchanged, then the only determining factors are the status quo level of agency competence as well as the level of agency competence that would be induced by an appointment. If the status quo level of agency competence is above (which corresponds to the area to the right of on the x-axis), indicating that the agency is minimally able to update its expectation of the state of the world given the observed signal (recall Lemma 1 and the subsequent discussion), then no appointment will occur if doing so will result in lower induced agency competence (which corresponds to the area below the 45° diagonal line). However, if an appointment will weakly increase agency competence (thereby implying that both and are equal to or greater than ), then appointments will occur—and these individuals will be placed into legislatively-confirmed positions (as they will not affect agency ideology regardless of their position, and will have a stronger positive effect on induced agency competence—which is preferable to both the executive and the legislature—if placed in a legislatively-confirmed position).

Conversely, if the status quo level of agency competence is less than , then the determining factor is whether the induced level of agency competence—conditional on a legislatively-confirmed appointment—will be greater than or equal to . If so, then since this represents an increase in competence relative to the status quo (and since the agency ideology will be unaffected), a legislatively-confirmed appointment will occur, as doing so allows the executive and the legislature to extract as much utility as possible from the increased level of agency competence (due to the greater influence of these types of appointments). On the other hand, if the induced level of agency competence—conditional on a legislatively-confirmed appointment—will be less than , then a unilateral appointment will occur, as the level of agency competence does not enter into the principals’ utility functions once it drops below .

When the potential appointee’s ideal point is not at the status quo, and the ideological balance between the executive and the legislature will be affected, then the appointment dynamics are somewhat more nuanced. I begin with the situation where an appointment would move the agency’s preferences closer to those of the executive and away from those of the legislature (figure 6). Here, it is rather intuitive that the executive would like to get these people into office in some capacity, so long as they will induce sufficient agency competence, or if they will not do so, then either (a) the benefits of agency competence () are comparatively low; or (b) the relative influence of unilateral appointees is rather low (as the legislature will be reluctant to confirm in these cases). The leftmost column of figure 6 displays the outcomes when the benefits of agency competence are sufficiently low; in these cases, unilateral appointments always occur in equilibrium. However, as the benefits of agency expertise increase (moving from the leftmost pane, to the middle pane, and finally to the rightmost pane), legislatures become more willing to confirm appointees, as the additional benefits of agency competence (or rather, the additional disutility from agency incompetence, given the structure of the utility functions) outweigh the legislature’s loss on the ideological dimension.

We also note that, as before, higher levels of induced agency competence generally (weakly) increase the likelihood of an appointment of some sort. However, when the potential appointee will move agency policy toward the preferences of the executive, the executive might be willing to settle for lower levels of induced agency competence and make unilateral appointments, so long as the status quo level of agency competence is sufficiently high and the unilateral position will be relatively powerless relative to legislatively-confirmed positions. This is because of the decreasing marginal utility of agency competence (recall the quadratic shape of the right-hand side of figure 4); in these cases, when the status quo level of agency competence is sufficiently high, somewhat lower levels of induced agency competence can be offset by gains on the ideological dimension. This is illustrated most clearly in the middle column of figure 6 (and especially the top row), with unilateral appointments more likely at the highest levels of status quo agency competence when the relative influence of the unilateral appointments is sufficiently low. However, the willingness of the executive to make this tradeoff (as well as the willingness of the legislature to be complicit) decreases as the benefits of agency competence increase—as indicated in figure 6, appointments that result in lower levels of induced agency competence become less likely overall as increases.

Appointment dynamics are somewhat different when the appointment will move agency policy away from the preferences of the executive and closer to that of the legislature (figure 7). In these cases, it is relatively straightforward that appointments will be less likely overall (given the level of executive discretion involved), and unilateral appointments in particular will be significantly curtailed. In particular, special attention will be paid to agency competence in these cases, as the executive will require a significant amount of utility gain on the competence dimension in order to offset losses on the ideological dimension. Perhaps the most obvious manifestation of this dynamic is in the leftmost column of figure 7, which suggests that no appointments will occur in equilibrium if the appointment will move agency policy away from the preferences of the executive and the benefits of agency expertise are sufficiently low or if the appointment will reduce agency expertise.

However, if an appointment will increase agency competence and move agency policy away from the preferences of the executive, successful appointments may occur in equilibrium. Because of the way competence enters into the utility functions, a necessary condition for appointments to occur in this case is if the induced agency competence will be sufficiently greater than . If these conditions are met, then appointments of some type will occur if the benefits of agency competence are sufficiently high and the status quo level of agency competence is not too high (since in these cases, the marginal decreasing utility of agency competence means the executive will not be able to increase agency competence to a sufficient extent to offset ideological loss). Legislatively-confirmed appointments will occur if the status quo level of agency competence is sufficiently low and the unilateral appointment option is not too influential; if the unilateral option is sufficiently influential, then the (smaller) increase in agency competence from that option may outweigh the (smaller) ideological loss to a greater extent than a similarly-situated legislatively-confirmed appointment (again, due to the marginal decreasing utility of agency competence). As the benefits of agency expertise increase, however, legislatively-confirmed appointments become more common, even if they will result in ideological losses for the executive.

Finally, figure 8 presents an example where the status quo may be pulled closer to both the executive and the legislature (such as after an election in which party control of at least one branch changes). In this case, the attractiveness of making an appointment wherein utility derived from ideology may be increased for both players means that legislative confirmations are more likely to occur, especially when is sufficiently low; in these cases, there is virtually no loss to be had in terms of utility derived from competence, and much to gain in terms of ideological utility. However, when the status quo agency competence is sufficiently high, and the benefits of agency expertise are not too low, then familiar dynamics reemerge. In these cases, higher levels of status quo agency competence correspond to more failed appointments, especially when the nominees will not sufficiently maintain and/or raise agency competence.

These results are stark in part because I make no explicit assumptions about patronage and yet uncover myriad situations that seem to mirror outcomes of patronage appointments; this is arguably because it is rather straightforward to see how such appointments might fit into the framework as given. Indeed, there exists a significant body of work that suggests the archetypal “patronage appointee” is, at best, no more competent than more professional types, and at worst possess significantly less subject- and task-level experience (e.g., Gallo and Lewis 2012; Hollibaugh 2015a; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Lewis 2007; Lewis 2008; Lewis 2009). Focusing on the type of potential patronage appointee that, if given the chance, will not move agency policy away from the executive, yet does not have significant expertise and/or experience, it is clear that that these people will be all but guaranteed to be placed into positions so long as the status quo agency competence is sufficiently low, as evidenced by the left sides of the plots in figures 5, 6, and 8, as well as Proposition 2.29 Additionally, whereas my stylized model presents a one-shot scenario, and therefore cannot capture the complicated dynamics that occur when multiple appointments over time are considered, the results suggest one method by which “turkey farms” can develop over time. That is, if an agency’s status quo level of competence is sufficiently low, it will seem like a good home for friendly-yet-underqualified appointees (as the decrease in agency competence—or even maintenance of a low level of competence—will not in and of itself reduce the utility of the appointing principal), and the accumulation of such individuals keeps agency competence low, thus ensuring that the agency will remain an appealing home for future such appointees (so long as they are sufficiently ideologically compatible). Moreover, these dynamics will be enhanced as patronage utility increases, as this strictly increases the utility of appointments of all types.

That said, it bears repeating that so long as there are no negative consequences on the policy dimension, executives do not need the enticement of significant patronage utility to appoint individuals to low-performing agencies. Indeed, figures 5, 6, and 8 show that, if agency policy will not be moved away from the preferences of the executive, appointments will be guaranteed if , even if agency performance is decreased as a result. Moreover, although this is even further beyond the scope of the model as written and would instead require a dynamic framework with multiple agencies, it seems likely that executives will be reluctant to “waste” highly-qualified appointees on agencies with sufficiently low levels of competence—as the marginal effect of agency competence on the principals’ utility function is only nonzero once —and will instead prefer to continue to staff the agency with those with lower levels of competence and expertise. If so, agencies could very easily get “trapped” in a cycle of incompetence, only escaping in the presence of some unmodeled exogenous shock. On this note, extensions of the model to incorporate long-run dynamics and/or the ability to select from multiple agencies would be useful to better unpack these dynamics, though the results here are suggestive on their own. Additionally, it might be useful to incorporate the extent to which the executive cares about the policy area for which the agency in question is responsible, as previous research has shown that executives place more highly-qualified individuals into agencies responsible for their policy priorities (Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Jo and Rothenberg 2012; Lewis 2008; Lewis 2009).30

Discussion and Conclusion

This article presented a model of the executive appointments process in which the goal is to find the optimal position for a given individual, as opposed to finding the best individual for a given vacancy. Substantively speaking, this process more closely mirrors the modern patronage selection process, in which positions are found for “necessary-to-place” individuals who contributed to the president’s and/or the president’s party’s fortune in some way, or otherwise have some connection that requires they be given a position (such as support from an influential member of Congress). This setup is in stark contrast to most existing models of the appointments process, which begin from the presumption that a vacancy exists, and the goal is to fill it with an individual who will (perhaps conditionally) maximize the utilities of the principals involved. Based on this setup, I derive conditions under which agency expertise will be lowered, as well as conditions under which potential nominees—regardless of their level of expertise—will be given some sort of position.31,32

The relatively simple model presented here is instructive and suggests one theoretical rationale—the structure of the person-centered appointments process—for the existence of “turkey farms,” or agencies that become targets for the placement of less-qualified administrators. Oftentimes, these are the agencies where well-connected job-seekers, key donors, and campaign staff are placed after an election. Indeed, I find that if the status quo level of agency expertise is sufficiently low, and the appointee will not move agency policy away from the preferences of the executive, then an appointment of some type is guaranteed under a person-centered appointments process (per Proposition 2). Perhaps more worryingly, it is under these same conditions (when agency expertise is sufficiently low) that reductions in agency competence have no detrimental effects on the utilities of the appointing principals. These results suggest that if patronage-seekers are sufficiently lacking in expertise, they will likely be placed into underperforming agencies, potentially exacerbating the agency’s performance issues and “trapping” the agency in a cycle of incompetence.

Additionally, that the results presented herein are largely driven by the status quo level of agency competence has implications for acting positions and officeholders whose duties change despite their formal positions remaining the same. An individual who finds himself or herself forced into a more influential position in an acting capacity due to a vacancy—especially if the vacancy is longer-term or the position is one where a person serving in an acting capacity would not normally be considered due to expertise and/or experience considerations—might have deleterious consequences for agency performance. In extreme cases, these acting officials might inadvertently reduce agency competence to the point where competence no longer enters into the principals’ utility function and the agency therefore falls into the “incompetence trap.”

However, it should be noted that the model presented herein—although arguably a closer match to certain person-centered appointments processes—is quite simple, and there are considerable opportunities to extend the model to perhaps better reflect the underlying dynamics at work. Foremost, although the assumption of no executive or legislative knowledge of the state of the world is standard and aids in the derivation of analytic results, it is certainly unrealistic, as both the executive and the legislature likely have some information (even if less than the relevant agency) about the state of the world; moreover, this information likely guides the selection and placement of the particular agent in question (and the decision of the legislature conditional on a nomination).

Additionally, the use of a uniform distribution for the state of the world is likely somewhat unrealistic as well—though it does provide for additional analytical tractability—since it effectively presumes that policies are likely to be equally biased in both “liberal” and “conservative” directions, and that “big” errors are just as likely as “small” errors; the former assumption results from the use of a symmetric distribution, and the latter results from the use of the uniform distribution in particular. Future models of the appointments process might benefit from more flexible distributions of the state of the world that allow for both skew and asymmetry.

Those caveats aside, the saga of FEMA during the administration of George W. Bush is instructive with respect to the phenomenon of the “incompetence trap.” Hired in February 2001 by then-FEMA Director (and college friend) Joe Allbaugh, Michael Brown was an arguably qualified candidate for his position of General Counsel; though he had no previous disaster management experience, he was a member of the Oklahoma bar and an adjunct instructor of law at Oklahoma City University.33 However, in early September 2001 he was tapped by Allbaugh to take a more policy-relevant and influential role as Acting Deputy Director, and he was later nominated by then-President Bush in February 2002 to take the position permanently; he was successfully confirmed via voice vote in August of 2002.34 Several months later, he was appointed Under Secretary of Emergency Preparedness and Response (colloquially referred to as the Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency) within the newly organized Department of Homeland Security (DHS); notably, there was no confirmation hearing, as a Congressionally-authored DHS rule waived reconfirmation for DHS employees whose job description “would not substantially change” when transferred to DHS (Mycoff and Pika 2007, p. 189).

When the relatively inexperienced (at least in terms of disaster management policy) Brown became Acting Deputy Director in September 2001, he replaced John Magaw, who had been serving as FEMA’s head of domestic terrorism preparedness activities and had been with the agency since 1999. However, it should be noted that prior to that, Allbaugh—who had no disaster management experience, having served as President Bush’s chief of staff during his governorship and campaign manager during his Presidential run—had been confirmed by the Senate as a replacement for former Director James Lee Witt—who had been head of the Arkansas Office of Emergency Services prior to his appointment—thus making it likely that FEMA’s level of agency competence had dropped precipitously prior to Brown’s assumption of the Deputy Director duties.35 Given those developments, it is certainly possible that the relatively inexperienced Brown’s ascension to Acting Deputy Director further reduced agency competence, perhaps below the level necessary to remove agency competence from the principals’ utility functions. If so, this is consistent with the actions taken by the then-Democratic Senate in August 2002 to confirm Brown to what was essentially his then-current job, as well as then-President Bush’s decision to nominate him in the first place, since doing so would maintain the status quo and Brown was—to some extent—deserving of an appointment (as a close friend of then-Director Allbaugh, it is plausible that Brown found himself in the category of those “absolutely deserving” of appointments, and his case would certainly have been aided by already serving in an acting capacity).36 Several months later, he was unilaterally appointed to be Administrator of FEMA; it is plausible that his appointment to an even more influential position within FEMA was in part due to his previous appointments (as well as the recent reorganization of the agency) reducing agency competence to a level where neither principal considered it in their utility functions. He resigned 2 years later following Hurricane Katrina and the increased media scrutiny of the agency that ensued, and after the perceptions of the benefits of agency expertise undoubtedly increased due to the fallout from FEMA’s response to Hurricane Katrina, he was replaced by R. David Paulison, Miami-Dade fire chief and the man responsible for cleanup after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 and the ValuJet Flight 592 crash in 1996 (Lewis 2008).37

Notably, the key event in the rise of Michael Brown to the position of FEMA Administrator, despite having no disaster management experience prior to joining the agency, may have been his assumption of Deputy Director duties in an acting capacity. However, that this was possible was largely due to the confluence of the person-centered appointments process and the focus on the status quo agency characteristics as the point of reference. Although the latter are likely difficult to change with policy reforms, it may be worthwhile for policymakers to consider expertise requirements for those who are unilaterally appointed yet might need to assume acting authority for positions normally filled via the advise-and-consent process.38

Finally, that the results herein suggest that a person-centered appointments process leaves agencies vulnerable to subpar performance suggests that the issue is not only of interest to public administration scholars and political scientists, but that policymakers should also take heed. That agency performance might be negatively affected not only by the political priorities of the appointing administration or variation in the pool of possible appointees, but also by the structure of the appointments process itself, suggests that those in charge of staffing the president’s administration might be wise to examine possible alterations to the process to ensure agency expertise is not substantially reduced in the name of providing appointed positions to the “absolutely deserving.” In this context, it might be wise to revisit previous calls to limit the influence and importance of appointees within the bureaucracy. Cohen’s (1998) call to “limit political appointments to the top two positions in each department and to their immediate special assistants” seems particularly relevant here, as one way of reducing the susceptibility of the structure of the appointments process to reducing agency expertise might be to eliminate the appointments process entirely (p. 450).39 However, doing so in the interest of enhancing administrative competence would raise other questions about public responsiveness and democratic public administration. For example, Bawn (1995) notes that “administrative procedures designed to prevent bureaucratic drift also limit the agency’s ability to research policy consequences or to make decisions that reflect its expertise” and that “the isolation and independence necessary for objective expertise make an agency’s political responsiveness highly sensitive to the personal preferences of its staff, making agency decisions hard to predict and hard to control” (p. 63), which—collectively—can be construed as an agency-level version of the loyalty-competence tradeoff. More broadly, this is an inherent tension between objective expertise and responsiveness to those political principals elected by the populace (who implicitly expect the bureaucracy to implement the preferred policies of their elected representatives).40 In any event, the results presented herein suggest that the structure of a person-centered appointments process should raise questions about how such a process affects the delicate balance between bureaucratic competence and democratic responsiveness.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory online.

References

———.

———.

———.

———.

———.

———.

———. Forthcoming.

———.

———.

———.

———.

As recorded by Martha Joynt Kumar (Untermeyer 1999, p. 30).

Falcone, Michael. 2008. “Applications Accepted.” The New York Times. November 8, 2008. Page A17.

Calmes, Jackie. 2008. “For a Washington Job, Be Prepared to Tell All.” The New York Times. November 13, 2008. Page A1.

Lewis, Neil A. 2008. “300,000 Apply for 3,300 Obama Jobs.” The New York Times. December 6, 2008. Page A10.

For example, President Clinton famously wanted an executive branch drawn from diverse demographics—one that “look[ed] like America” (Weko 1995, p. 101). Gump (1971) argues that patronage has value in “generating campaign contributions” and “obtaining campaign effort” (p. 107). See also Parsneau (2013).

Although this article is ostensibly focused on the executive nominations process, it should be noted that patronage considerations are present even within the nominations process for judicial vacancies, as “candidates for the federal bench receive their nominations precisely because through their political work or interests they came to the attention of some politician, most likely a U.S. Senator or a member of the president’s staff” (Epstein and Segal 2005, p. 3).

Although the exact origin of the term “turkey farm” in this context is difficult to ascertain, a report from the House Appropriations Committee in 1992 described the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as such:

“FEMA is widely viewed as a ‘dumping ground,’ a turkey farm, if you will, where large numbers of positions exist that can be conveniently and quietly filled by political appointment. This has led to a situation where top officials, having little to no experience in disaster or emergency management, are creating substantial morale problems among careerists and professionals” (as quoted in Brasch [2005], p. 23).

Therefore, I will use the term “turkey farm” to refer to agencies that have high numbers of minimally-competent—but necessary-to-place—individuals among their ranks. That said, the notion of using particular departments and agencies as dumping grounds for less-competent individuals has a longer history. For example, a 1976 Senate Commerce Committee report on FCC appointments called the agency “a convenient dumping ground for people who have performed unsatisfactorily in other more important government posts” (United States Senate Committee on Commerce 1976, p. 391). Going even further back, the 1885 annual report from the Department of the Interior noted that its Pension Bureau had, “at one time and another been used as a ‘dumping ground’ for other offices, [and some] very weak and very bad material has accumulated” (United States Department of the Interior 1885, p. 110).

Robert Nash, Director of the OPP under President Clinton, said that he would not “find somebody and put them in an important position who is not capable of doing it, because they worked in the campaign” (Nash 2000, p. 17). Along these same lines, Chase Untermeyer, who held the same position during George H. W. Bush’s administration, noted that those who had given a great deal during the campaign but had “limited abilities in governing” could be “accommodated…in other ways,” including “invitations to state dinners or other things that are within a gift [sic] of the president to do short of putting that person in charge of a chunk of the federal government” (Untermeyer 1999, p. 9).

Lewis (2008) puts the number of executive branch appointees subject to Senate confirmation at 1,137 in 2004, compared to 2,270 appointees not subject to Senate confirmation.

Although the Senate does not pose an institutional obstacle per se, Senators will oftentimes attempt to influence the appointments process informally for unconfirmed positions as well.

That neither the executive nor the legislature have any knowledge of at the time of nomination—aside from its distribution—is a standard assumption in many models of delegation. While relaxing this assumption—either in terms of the available information or the beliefs thereof—would complicate the model to a significant extent, the fundamental results discussed here—that a person-centered appointments process provides incentives for agency incompetence under certain conditions—would be unaffected (though the underlying conditions might change).

One might object to the assumption that both the executive and the legislature are equally certain—or uncertain—about the benefits of agency expertise. This is done for the purposes of focusing the model on the structure of the appointments process, and relaxing this assumption does not change the comparative statics to that end, though it does reduce mathematical tractability.

See Jo and Rothenberg (2012) for an example of an alternative formulation.

Thus, if , then Moreover, if is the unconditional distribution of , and is the conditional distribution of given , then Substantively speaking, as agencies become less competent, the observed signals provide less information.

Given this operationalization, “competence” almost by necessity refers strictly to informational competence, where the ability of agencies to discern the true state of the world is of prime importance. Other conceptions of competence—such as political competence (Maranto 1998; Maranto 2005) and policy competence (Callander 2008; Callander 2011)—might be of interest to readers, but are beyond the scope of this article.

Both figures were generated using However, different sets of parameter values generate substantively identical plots.

The middle two conditions of Lemma 1 imply that if c = 1/2, then and no adjustment takes place. Moreover, Lemma 1 implies that if , then , regardless of c.

In figure 2 and the rest of the article, “induced” agency competence refers to the level of agency competence subsequent to a successful appointment. Induced agency ideology is analogously defined.

For example, if the agency observes , it can be certain that the true is not Ω, regardless of its level of competence.

Relatedly, Lee and Whitford (2013) note that higher levels of employee professionalization are associated with higher levels of agency effectiveness.

As recent work has illustrated the importance of personality to elite decisionmaking (e.g., Dietrich et al. 2012; Gallagher and Allen 2014; Gallagher and Blackstone 2015; Hall 2015; Klingler, Hollibaugh, and Ramey forthcoming; Klingler, Hollibaugh, and Ramey 2016; Ramey, Klingler, and Hollibaugh 2016; Ramey, Klingler, and Hollibaugh 2017; Rubenzer and Faschingbauer 2004), this could also be another source of utility and—by virtue of personality not being a direct driver of policy-related utility—a potential cause of agency incompetence. However, while intriguing, I do not focus on this possiblity here.

Note that I assume all nonstochastic parameters in the model are known to the executive and the legislature at the time appointments are made. As I discuss later, this is unlikely to change the larger substantive conclusions, and the cost of relaxing this assumption will be substantial mathematical complications. More subtle is the distinction between bargaining over individual appointments, and the assumption that the agency as a whole observes the state of the world and implements policy. However, explicitly incorporating this distinction into the model would result in the addition of a new parameter that captures the influence of the individual legislatively-confirmed appointments (which would presumably be multiplied by to capture the relative influence of unilaterally-appointed individuals) would complicate the model and provide no additional substantive insight. Instead, I simply focus on the induced or ex post agency ideology and agency competence (versus the status quo), as these implicitly capture the effect the appointee will have no the agency and is easier to parameterize.

Although it may seem odd to parameterize unilateral appointments in terms of the legislatively-appointed counterfactual and the status quo, this formulation is a tacit acknowledgement of the fact that unilateral appointments—on average—are less likely to have direct authority over policy. As such, so long as , the formulation substantively reflects this reality, even if it is a bit jarring upon first glance. Additionally, the model’s results are not dependent on being included in both the and equations; rather, the conclusions are substantively similar if individual ideology- and competence-specific parameters are used, though some mathematical tractability is lost.

Other scholars have found situations in which principals desire less-competent agents in equilibrium (or at least do not seek to maximize agency competence), though these models typically make additional assumptions about the political contexts in which the principals operate. For example, Jo and Rothenberg (2012) uncover situations in which incompetent appointees will be appointed in equilibrium, with incompetence translating into increased policy uncertainty. However, this model relies on the assumption that the parties place differing weights on policy utility.

It should also be noted that Bendor and Meirowitz (2004) find similar results for entire classes of games, in that superiors delegate less often to “informationally imperfect” agents.

I assume no informational asymmetries in the event of a nomination, so the executive’s expectations of what the legislature will do are always correct.

As mentioned earlier, these results are predicated upon the assumption that the executive and legislature are perfectly informed about the ideology and competence of the potential nominee in question—and therefore about the induced agency ideology and expertise that will result—and this is obviously a simplification. However, relaxing this assumption would likely leave the comparative statics mostly unchanged while complicating the mathematics. On this point, Sen and Spaniel (2015) develop a model of the judicial nominations process in which the ideology of the nominee is unknown. They find that when the executive and the legislature agree on policy, then uncertainty enables the executive to put forth more extreme nominees than she could otherwise; conversely, when the executive and the legislature are ideologically divergent, then uncertainty ensures that some otherwise confirmable nominees will be rejected. This suggsts that uncertainty might simply exacerbate the ideological conflict between the executive and the legislature and—depending on the parameter values chosen—will either expand (when ideological convergence between the executive and the legislature is high) or contract (when convergence is low) the set of nominees confirmable by the legislature. However, these dynamics will not change the overall conclusion that—under certain conditions—certain agencies can become targets for less-competent nominees, who may therefore induce lower levels oagency competence.

Note that this is a sufficient condition and not a necessary condition.

But see Parsneau (2013).

Importantly, I do not claim that preexisting subpar performance or incompetence are the sole mechanisms by which “turkey farms” may arise. Expanding the model to incorporate patronage explicitly—along with the commensurate assumption that patronage appointees tend to be less competent than other types (Gallo and Lewis 2012; Lewis 2007; Lewis 2008; Lewis 2009; Hollibaugh, Horton, and Lewis 2014; Hollibaugh 2015a)—or varying levels of policy priority would allow me to derive “turkey farms” from causes beyond those discussed in the model presented above, and would almost certainly show an interaction between the various dynamics. However, the goal of this article, by assuming away the influence of patronage or policy importance, was to show that a person-centered appointment process—in and of itself—could lead to agencies becoming “turkey farms.”

In principle, one could test these theories empirically—or even pit them against each other (using the appropriate nonnested model tests [Clarke 2007; Vuong 1989] to discern between them)—using appropriate panel data. Ideally, one would need measures of agency performance and presidential policy priorities over time, as well as individual-level appointee data. While an interesting research question, I leave it for future researchers.

Lawrence, Jill. 2005. “FEMA director faces his own storm of controversy.” USA TODAY. September 7, 2005. Page 5A.

Hearing before the United States Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs on the Nomination of Michael D. Brown to be Deputy Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, June 19, 2002. https://www.congress.gov/107/chrg/shrg81311/CHRG-107shrg81311.htm.

Claiborne, William. 1993. “Panel Backs Nominee For Disaster Agency; Clinton Pick Pledges Better Days at FEMA.” Washington Post. April 1, 1993. Page A21; Marquis, Christopher. 2001. “Man in the News; A Tough-Talking, but Self-Effacing, Loyalist; Joe Marvin Allbaugh.” New York Times. January 5, 2001. Page A14.

It should be acknowledged that the Democratic Senate was showing a significant amount of deference to President Bush in the months following the September 11 attack, and this deference would have likely been higher on matters of disaster management, which are more easily linked to foreign policy concerns than most domestic policy issues (Howell, Jackman, and Rogowski 2013).

McNamara, Melissa. 2006. “Bush Nominates New FEMA Director.” CBS News. April 6, 2006. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/bush-nominates-new-fema-director/.

In particular, those officials deemed “first assistants” per 5 U.S. Code 3345.

Also see the 2003 report of the National Commission on the Public Service (2003), which argued that an “essential first step toward improvement [in the appointments process] is a significant cut in the number of political executive positions” (p. 20). Additionally, Light’s (1995) warnings about the “thickening” of bureaucratic hierarchies are also particularly relevant here, especially when considered in light of Jo and Rothenberg’s (2014) finding that the hierarchical structures of bureaucracies result in incomplete political control and undercut the ally principle, which further incentivizes politicization via the appointment of political allies at lower levels.

Relatedly, Krause and Douglas (2005) and others suggest that agency reputation may mitigate some of the expertise loss induced by attempts at political control. In this vein, it is certainly conceivable that strong reputations lead political principals to perceive as being high, thus shielding these agencies from appointees that may damage agency expertise, and therefore preserving the agency’s reputation. Also see Lee and Whitford (2013).

Author notes

Address correspondence to the author at gholliba@nd.edu.