-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mathew D Gayman, Ben Lennox Kail, Amy Spring, George R Greenidge, Risk and Protective Factors for Depressive Symptoms Among African American Men: An Application of the Stress Process Model, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 73, Issue 2, February 2018, Pages 219–229, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx076

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study employs the stress process model (SPM) to identify risk/protective factors for mental health among adult African American men.

Using a community-based sample of Miami, FL residents linked to neighborhood Census data, this study identifies risk/protective factors for depressive symptomatology using a sample of 248 adult African American men.

The stress process variables independently associated with depressive symptoms were family support, mastery, self-esteem, chronic stressors, and daily discrimination. While mastery and self-esteem mediated the relationship between neighborhood income and depressive symptoms, perceived family support served as a buffer for stress exposure. Collectively, the SPM explains nearly half of the variability in depressive symptoms among African American men.

The SPM is a useful conceptual framework for identifying psychosocial risk/protective factors and directing health initiatives and policies aimed at improving the psychological health of African American men.

Although African Americans are less likely to meet criteria for major depressive disorder than whites (Kessler et al., 2005), they are at increased risk for depressive symptoms (Gilster, 2014; Jang, Borenstein, Chiriboga, & Mortimer, 2005; Plant & Sachs-Ericsson, 2004; Skarupski et al., 2005; Turner et al., 2004). Given their unique and disadvantaged social position (Williams & Sternthal, 2010), research identifying factors that contribute to depressive symptoms among African American men is warranted (Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2011; Watkins, 2012). Such research is particularly important since depressive symptoms are linked to increased risk for suicidality (O’Connor & Nock, 2014).

Few studies have focused on African American men to identify risk and protective factors for psychological well-being (Gilbert et al., 2016; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011), particularly depressive symptoms (Hammond, 2012). However, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the role of factors such as socioeconomic status, social stressors (including discrimination), and psychosocial coping resources for depressive symptoms among African American men (Watkins, Green, Rivers, & Rowell, 2006). Collectively, these factors constitute what Stress Process researchers recognize as key risk and protective factors for health and health inequalities.

The basic tenet of the stress process model (SPM) is that health problems are not randomly distributed across society but rather systematically biased against those with lower social status (Pearlin, 1999). One important social status is an individual’s location within dimensions of socioeconomic status (SES). One dimension is individual SES, which represents the resources available to individuals. Another dimension is neighborhood SES, which reflects one’s exposure to everyday contextual forces that can be beneficial (or harmful) for mental health (Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010; Ross & Mirowsky, 2001). High SES may promote good mental health but the role of SES for depressive symptoms is unclear for African American men, a population heavily impacted by race disparities in both individual and neighborhood SES. Thus, in addition to their status as a racial minority, African American men may be at high risk for poor psychological health due to lower individual and neighborhood SES.

Research on the relationship between individual-level SES and depressive symptoms among African American men is mixed and some evidence indicates that African American men may not reap the same benefits from SES as whites (Williams, 2003). Additionally, little is known about the role of neighborhood-level SES for depressive symptoms among African American men.

Minority status and low SES experienced by African American men can also translate into poor health outcomes through increased stress exposure and limited psychosocial coping resources (Pearlin, 1999). Minority status and low SES are associated with higher social stress and lower psychosocial resources such as perceived social support, mastery, and self-esteem (Turner, Taylor, & Van Gundy, 2004; Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995). Although these factors have been shown to be particularly important for psychological well-being of African American men (Watkins, 2012), it is unclear which SPM variables independently contribute to depressive symptoms among African American men, and which of these factors mediate the SES—depression relationship.

Also within the SPM framework, understanding the potential stress-buffering (or moderating) effects of psychosocial coping resources is important for understanding factors that contribute to depressive symptoms among African American men. Specifically, the stress-buffering hypothesis states that the negative mental health consequences of stress exposure are weakened at higher levels of coping resources and/or is magnified at low levels of coping resources. Because few studies have tested the stress-buffering effects of coping resources by (or within) race (Gayman, Cislo, Goidel, & Ueno, 2014), this study advances prior research by assessing the stress-buffering effects of various psychosocial coping resources known to be associated with mental health among African American men.

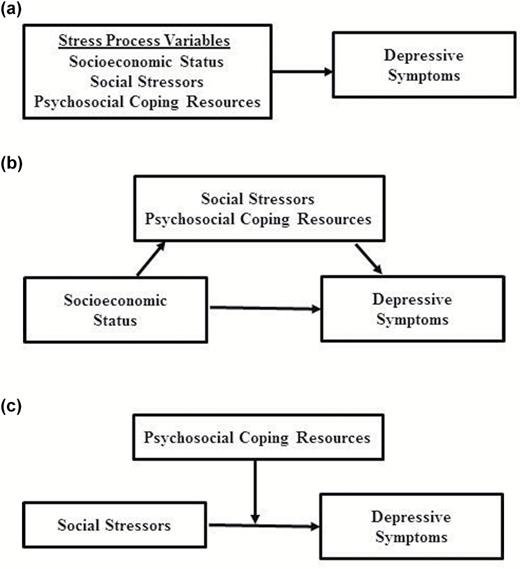

Despite considerable evidence demonstrating the utility of the SPM for understanding depressive systems in the general population (Turner 2010), this is one of the few investigations to apply the model specifically to African American men. This study considers a wide range of SPM variables to evaluate the (a) overall explanatory power of the SPM and identify the SPM factors that contribute independently to depressive symptomatology, (b) mediating effects of social stress and coping resources for the SES—depressive symptom relationship, and (c) stress-buffering effects of psychosocial coping resources.

Background

African American men are at greater risk for depressive symptoms than their White counterparts (Gilster, 2014; Jang et al., 2005; Skarupski et al., 2005; Turner et al., 2004). Although African American men report fewer symptoms than African American women (Miller & Taylor, 2012), possibly due to gender differences in symptom expression (Walton & Shepard, 2016) or risk/protective factors (Griffith, Ellis, & Allen, 2013), more than 6% of African American men report 16 or more symptoms (Lincoln et al., 2011). Sixteen or more symptoms is often used to determine clinical-level depression (Lewinsohn, Seeley, Roberts, & Allen, 1997) and this underscores the importance of research identifying factors that contribute to depressive symptoms among African American men (Ward & Mengesha, 2013).

The SPM has been shown to be a powerful framework for understanding risk and protective factors for depressive symptomatology, as well as race disparities in depressive symptoms. Indeed, an estimated one-third to one-half of the variability in depressive symptoms, and all of the Black-White disparity in depressive symptoms, is explained by the SPM (Turner & Lloyd, 1999; Turner et al., 2004). Although few studies have applied the SPM to understand the psychological well-being of African American men, there are reasons to anticipate that SPM variables will contribute to depressive symptoms among African American men. For example, low SES and greater discrimination may be particularly important for depressive symptoms among African American men. Conversely, high levels of self-esteem consistently reported by African Americans (Taylor & Turner, 2002; Turner et al., 2004) may serve as an important protective coping resource for the psychological health of African American men.

In one of the first studies examining risk/protective factors for depressive symptoms among older African American men, income was associated with depressive symptoms at the bivariate level but not after adjusting for psychosocial coping resources such as mastery and social support, which highlights the mediating role of psychosocial resources for the SES—depression relationship (Weaver & Gary, 1994). In a separate analysis examining social stressors, both major life events and chronic stressors were independently linked to depressive symptoms, but did not mediate the SES—depression relationship (Weaver & Gary, 1994). However, because psychosocial coping resources and social stressors were not modeled simultaneously, the independent contribution of these SPM variables for the psychological health of African American men is unclear. This study also does not include self-esteem or neighborhood-level SES, both factors known to be associated with depressive symptoms and race minority status. Despite these limitations, this study provides important insight and, to date, remains one of the few studies to comprehensively account for various SPM variables when predicting depressive symptoms among African American men. However, there is growing research demonstrating the importance of elements of the SPM for depressive symptoms among African American men.

Socioeconomic Status

Higher levels of both individual- and neighborhood-level SES are associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Turner & Lloyd, 1999; Roux & Mair, 2010). People with higher SES are better positioned to avoid health risks and problems through the deployment of knowledge, money, power, support networks, and psychosocial coping resources (Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010). Thus, individual SES influences mental health not only through education and economic resources but also through the availability of psychosocial coping resources and the ability to avoid and/or overcome life hardships. Consistent with this perspective, almost all (91%) of the relationship between individual SES and depressive symptoms is explained by the SPM, which includes psychosocial coping resources, chronic stressors and discrimination (Turner & Lloyd, 1999).

Although higher SES is associated with fewer depressive symptoms among adult African Americans (Ida & Christie-Mizell, 2012; Marshall-Fabien & Miller, 2016), findings on the relationship between individual SES and depressive symptoms among African American men are mixed. Some studies have found that African American men reporting higher earnings experience fewer depressive symptoms (Lincoln et al., 2011; Mizell, 1999; Weaver & Gary, 1994) and other studies have found no relationship between individual SES and depressive symptoms (Hoard & Anderson, 2004; Kogan & Brody, 2010). African American men may not experience the same mental health benefits from higher SES as their White counterparts (Williams, 2003), possibly due to increased exposure to discrimination among higher SES African Americans compared to those with lower SES (Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus, & Jackson, 2016).

Lower neighborhood SES is associated with greater exposure to concentrated poverty, unemployment, and social stressors (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001). Although such exposures are related to depressive symptoms (Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016; Najman et al., 2010; Turner & Lloyd, 1999), little is known about the role of neighborhood SES for depressive symptoms among African American men. Neighborhood SES may be particularly important for African American men as they are at increased risk for residing in predominantly low-income neighborhoods that involve high levels of crime and disorder (Massey & Denton, 1993), which are psychologically noxious (Roux & Mair, 2010).

The current study builds on prior research by considering the contribution of both individual and neighborhood SES for the psychological health of African American men. Additionally, this study assesses the potential mediating effects of social stress and psychosocial coping resources in the SES—depressive symptom relationship.

Social Stressors

Exposure to social stress, especially chronic stressors, has deleterious mental health effects and nearly one-third of the variability in depressive symptoms is explained by stress exposure (Turner & Lloyd, 1999). Although everyone experiences life stressors, socially marginalized groups are exposed to a disproportionately higher number of stressors (Turner 2010). Indeed, even after adjusting for SES, African Americans experience significantly more exposure to chronic stressors and recent life events than whites (Turner & Avison, 2003).

Chronic stressors are recognized as important factors shaping the psychological well-being of African American men (Griffith et al., 2013). For instance, among older African American men, those reporting more chronic hassles and major life events were at increased risk for depressive symptoms (Weaver & Gary, 1994). Among young adult African American men, those reporting greater parent-young adult conflict experienced more depressive symptoms (Kogan & Brody, 2010) and, among African American fathers, greater parenting stress was linked to more depressive symptoms (Baker, 2013). In a sample of low-income, predominantly African American fathers, those reporting more chronic stressors also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms (Hoard & Anderson, 2004). Although social stressors are recognized as significantly contributing to African American men’s mental health (Watkins, 2012), the independent contribution of various sources of social stressors for the psychological well-being of African American men is unclear.

Additionally, while there is some evidence demonstrating that social stress partially mediates the association between income and depression among African American women (Schulz et al., 2006), little is known about the potential mediating role of social stressors for the SES—mental health relationship among African American men. This is particularly important given that low SES is linked to greater stress exposure (Turner & Avison, 2003) and the disadvantaged socioeconomic position experienced by many African American men. There is also a paucity of research evaluating the potential stress-buffering effects of psychosocial coping resources predicting depressive symptoms among African American men, which will be discussed shortly.

Daily Discrimination

As a social stressor, discrimination is also linked to poor mental health (Paradies, 2006). Although there is evidence indicating African American men report greater discrimination than women, it is unclear whether this gender disparity is due to differences in lived experiences or measurement bias (see Ifatunji & Harnois, 2016). Nevertheless, daily discrimination is important for the psychological health of African Americans (Taylor & Turner, 2002) and African American men experiencing more discrimination report worse mental health (Hammond, 2012; Watkins et al., 2011). Additionally, the mental health benefits associated with higher SES may be mitigated by experiences of racial discrimination among African American men (Hudson et al., 2012). Although these findings underscore the mental health significance of discrimination, few studies have assessed the independent contribution of discrimination for mental health net of other sources of social stress (Taylor & Turner, 2002), as well as the potential meditating effects of discrimination in the SES—depressive symptom relationship or the stress-buffering effects of psychosocial coping resources among African American men.

Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support refers to the feeling that one is loved, valued, and esteemed, and able to count on others should the need arise (Cobb, 1976). According to the SPM, perceived support serves as an important factor contributing both directly to mental health and indirectly as a mediator in the SES—depressive symptom relationship (Turner & Lloyd, 1999). Although African Americans report lower perceived social support than non-Hispanic whites (Gayman et al., 2014), social support is important for the mental health of African American men (Kogan & Brody, 2010). For example, among low-income, predominantly African American fathers, those perceiving more support report fewer depressive symptoms (Hoard & Anderson, 2004). Additionally, although some research has shown that social support does not mitigate the psychological harm stemming from financial stress among African Americans (Lincoln, 2007), perceived support has been shown to partially mediate the association between income and depression among African American women (Schulz et al., 2006). However, the independent contribution of perceived support for depressive symptoms and its potential mediation effect on the SES—mental health relationship, among African American men remains unanswered. In addition to direct and mediating effects, this study also assesses the stress-buffering effects of perceived social support. As with prior research (Gayman et al., 2014), we anticipate that perceived social support will condition the negative mental health consequences stemming from chronic stress exposure; whereby the negative impact of stress exposure on depressive symptoms will be weakened at higher levels of perceived support.

Mastery

Mastery refers to the sense that one has control over life circumstances and/or outcomes (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978), which is associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Turner & Lloyd, 1999). Although African Americans report less mastery than whites (Gilster, 2014; Turner et al., 2004), mastery is associated with fewer depressive symptoms among African American men (Jang et al., 2005; Mizell, 1999; Watkins et al., 2011; Weaver & Gary, 1994). Mastery has also been shown to mediate the relationship between SES and depressive symptoms (Turner & Lloyd, 1999), including among African Americans (Lincoln, 2007; Miller, Rote, & Keith, 2013). To date, however, few studies have assessed the additive, mediating and moderating effects of mastery for depressive symptoms among African American men.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to one’s sense of self-worth (Rosenberg, 1979), which is inversely associated with depressive symptoms (Gayman et al., 2010). Unlike with perceived social support and mastery, African Americans report higher levels of self-esteem than whites (Turner et al., 2004) and self-esteem serves as an important coping resource for African American men. Indeed, African American men with greater self-esteem report fewer depressive symptoms (Ida & Christie-Mizell, 2012; Mizell, 1999). However, little is known about the mediating role of self-esteem for the SES—depressive symptom relationship or the stress-buffering effects of self-esteem among African American men.

To date, few studies have focused on African American men to identify risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms (Hammond, 2012; Lincoln et al., 2011; Watkins, 2012). Depicted in Figure 1a–c, this study considers a wide range of SPM variables to evaluate the (a) independent contributions of SPM variables for depressive symptoms, (b) mediating effects of social stressors and psychosocial coping resources for the SES—depressive symptom relationship, and (c) stress-buffering effects of psychosocial coping resources.

(a) Additive effects. (b) Mediation effects. (c) Moderation effects.

Method

Sample

Data are from a community-based study of Miami-Dade County residents including a substantial oversampling of individuals with a self-identified physical disability (Turner, Lloyd, & Taylor, 2006). A total of 10,000 randomly selected households were screened based on gender, age, ethnicity, disability status, and language preference. Using this sampling frame, the sample was drawn to include an equivalent number of women and men, self-identified physical disability and no disability, and each of the four major ethnic groups comprising more than 90% of Miami-Dade County residents (non-Hispanic Whites, Cubans, non-Cuban Hispanics, and African Americans).

From 2000 to 2001, 1,986 interviews were completed (82% success rate). For purposes of this investigation, analyses are limited to only African American men (n = 254). Among the African American men, we excluded six respondents with missing data on any study variable. The analytic sample includes 248 African American men.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the highly reliable and widely used 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Participants were presented with such statements as “You felt depressed” and “You felt that you could not shake off the blues” in the past month, with response categories of 0 “not at all” to 3 “almost all the time.” Items were coded such that higher scores represent more symptoms and summed for analysis (mean = 7.87, SD = 7.80, range = 0–47, α = 0.86).

Socioeconomic Status

Individual SES was based on a three-item composite score equally weighing occupational prestige (Hollingshead, 1957), education, and household income of each participant. To avoid problems of missing data, scores on each dimension were standardized, summed and divided by the number of dimensions on which data were available. Preliminary analysis also considered individual SES dimensions separately and the results were substantively identical to those presented here. Neighborhood Income was measured using the median household income from the 2000 Census block-group data file.

Social stressors

Chronic stressors were measured using Wheaton’s (1994) scale, modified to better capture the kinds of stressors middle-aged to older adults are likely to experience. This includes 39 dichotomous items relating to general experiences, (un)employment, intimate partnerships/no partners, children, recreation, and health concerns. Responses to all 39 dichotomous items were summed (mean = 3.35, SD = 4.25, range = 0–26). Recent life events were measured using a 32-item index referring to past 12-month experiences ranging from a serious accident/injury to the death of a loved one. Responses to all 32 dichotomous items were summed (mean = 1.05, SD = 1.52, range = 0–9).

Daily discrimination

Discrimination was measured using a 9-item index (Williams, Yan Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Items include statements such as “You are treated with less courtesy than other people” and “People act as if they think you are dishonest,” with response categories of 1 “Never,” 2 “Rarely,” 3 “Sometimes,” 4 “Often,” and 5 “Almost Always.” The nine items were averaged (mean = 1.83, SD = 0.63, range = 1–4.22, α = 0.86).

Perceived social support

Social support was measured using a modified and shortened version of the Provisions of Social Relations scale (Turner, Frankel, & Levin, 1983). Family support (16-items) and friend support (8-items) were based on statements such as “You feel very close to your family(friends)” and “You feel that your friends really care about you,” with responses ranging from 1 “Not at all true,” 2 “Somewhat true,” 3 “Moderately true,” to 4 “Very true.” Items were coded such that higher values represent greater support, and averaged for family support (mean = 3.63, SD = 0.48, range = 1–4, α = 0.87) and friend support (mean = 3.36, SD = 0.83, range = 1–4, α = 0.95).

Mastery

Using an established scale (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978), mastery (7-items) was based on statements such as “I have little control over the things that happen to me” and “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to,” with responses ranging from 0 “Strongly Disagree,” 1 “Mildly Disagree,” 2 “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” 3 “Mildly Agree,” to 4 “Strongly Agree.” Responses were coded such that higher values represent greater mastery and averaged across the seven items (mean = 2.88, SD = 0.92, range = 0.29–4.00, α = 0.81).

Self-esteem

Using a six-item subset of Rosenberg’s (1979) measure, respondents were presented with statements such as “You feel that you have a number of good qualities” and “All in all, you are inclined to feel that you are a failure.” Responses were coded such that higher values represent greater self-esteem, ranging from 0 “Strongly Disagree,” 1 “Mildly Disagree,” 2 “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” 3 “Mildly Agree,” to 4 “Strongly Agree,” and averaged across the six items (mean = 3.76, SD = 0.42, range = 1.67–4.00, α = 0.69).

Controls

Age was measured in years. Disability status was measured by asking respondents if they responded affirmatively to having a condition or physical health problem that limits the kind or amount of activity that they can carry out (coded as 1 for disability and 0 for no disability). Marital status was categorized as “Married,” “Separated,” “Divorced,” “Widowed,” and “Never Married.”

Analysis Plan

First, descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. Second, ordinary least squared (OLS) regressions were used to assess additive and mediation effects of SPM variables for depressive symptoms (Table 2). Mediation analyses were conducted using a Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). Third, moderation analyses were used to assess stress-buffering effects of psychosocial coping resources (Table 3).

Descriptive Statistics for Depressive Symptoms and Stress Process Variables

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | % (N) |

| Depressive symptoms | 7.89 (7.79) | 0.00–47.00 | |

| Sixteen or more symptomsa | 10.89 (27) | ||

| Individual SESb | 0.00 (1.00) | −2.14–3.29 | |

| Neighborhood incomec | $34,409.84 (11,851.36) | $9,231–99,921 | |

| Chronic stressors | 3.31 (4.21) | 0.00–26.00 | |

| Recent life events | 1.05 (1.53) | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Daily discrimination | 1.82 (0.63) | 1.00–4.22 | |

| Family support | 3.63 (0.48) | 1.19–4.00 | |

| Friend support | 3.36 (0.83) | 1.00–4.00 | |

| Mastery | 2.89 (0.93) | 0.29–4.00 | |

| Self-esteem | 3.76 (0.43) | 1.67–4.00 | |

| Age | 58.11 (16.26) | 18.00–86.00 | |

| Physical disability (yes) | 32.66 (81) | ||

| Never married | 16.94 (42) | ||

| Married | 58.87 (146) | ||

| Divorced | 10.48 (26) | ||

| Widowed | 10.08 (25) | ||

| Separated | 3.63 (9) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | % (N) |

| Depressive symptoms | 7.89 (7.79) | 0.00–47.00 | |

| Sixteen or more symptomsa | 10.89 (27) | ||

| Individual SESb | 0.00 (1.00) | −2.14–3.29 | |

| Neighborhood incomec | $34,409.84 (11,851.36) | $9,231–99,921 | |

| Chronic stressors | 3.31 (4.21) | 0.00–26.00 | |

| Recent life events | 1.05 (1.53) | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Daily discrimination | 1.82 (0.63) | 1.00–4.22 | |

| Family support | 3.63 (0.48) | 1.19–4.00 | |

| Friend support | 3.36 (0.83) | 1.00–4.00 | |

| Mastery | 2.89 (0.93) | 0.29–4.00 | |

| Self-esteem | 3.76 (0.43) | 1.67–4.00 | |

| Age | 58.11 (16.26) | 18.00–86.00 | |

| Physical disability (yes) | 32.66 (81) | ||

| Never married | 16.94 (42) | ||

| Married | 58.87 (146) | ||

| Divorced | 10.48 (26) | ||

| Widowed | 10.08 (25) | ||

| Separated | 3.63 (9) |

Note: N = 248. SES = Socioeconomic status.

aReporting 16 or more depressive symptoms. bIndividual-level income is standardized to have a mean of zero and an SD of 1. cRepresents the average median household income based on block-group census data, with a median neighborhood level income of $32,868.

Descriptive Statistics for Depressive Symptoms and Stress Process Variables

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | % (N) |

| Depressive symptoms | 7.89 (7.79) | 0.00–47.00 | |

| Sixteen or more symptomsa | 10.89 (27) | ||

| Individual SESb | 0.00 (1.00) | −2.14–3.29 | |

| Neighborhood incomec | $34,409.84 (11,851.36) | $9,231–99,921 | |

| Chronic stressors | 3.31 (4.21) | 0.00–26.00 | |

| Recent life events | 1.05 (1.53) | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Daily discrimination | 1.82 (0.63) | 1.00–4.22 | |

| Family support | 3.63 (0.48) | 1.19–4.00 | |

| Friend support | 3.36 (0.83) | 1.00–4.00 | |

| Mastery | 2.89 (0.93) | 0.29–4.00 | |

| Self-esteem | 3.76 (0.43) | 1.67–4.00 | |

| Age | 58.11 (16.26) | 18.00–86.00 | |

| Physical disability (yes) | 32.66 (81) | ||

| Never married | 16.94 (42) | ||

| Married | 58.87 (146) | ||

| Divorced | 10.48 (26) | ||

| Widowed | 10.08 (25) | ||

| Separated | 3.63 (9) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | % (N) |

| Depressive symptoms | 7.89 (7.79) | 0.00–47.00 | |

| Sixteen or more symptomsa | 10.89 (27) | ||

| Individual SESb | 0.00 (1.00) | −2.14–3.29 | |

| Neighborhood incomec | $34,409.84 (11,851.36) | $9,231–99,921 | |

| Chronic stressors | 3.31 (4.21) | 0.00–26.00 | |

| Recent life events | 1.05 (1.53) | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Daily discrimination | 1.82 (0.63) | 1.00–4.22 | |

| Family support | 3.63 (0.48) | 1.19–4.00 | |

| Friend support | 3.36 (0.83) | 1.00–4.00 | |

| Mastery | 2.89 (0.93) | 0.29–4.00 | |

| Self-esteem | 3.76 (0.43) | 1.67–4.00 | |

| Age | 58.11 (16.26) | 18.00–86.00 | |

| Physical disability (yes) | 32.66 (81) | ||

| Never married | 16.94 (42) | ||

| Married | 58.87 (146) | ||

| Divorced | 10.48 (26) | ||

| Widowed | 10.08 (25) | ||

| Separated | 3.63 (9) |

Note: N = 248. SES = Socioeconomic status.

aReporting 16 or more depressive symptoms. bIndividual-level income is standardized to have a mean of zero and an SD of 1. cRepresents the average median household income based on block-group census data, with a median neighborhood level income of $32,868.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Stress Process Variables (Mediation)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Neighborhood income | −0.17** (0.00) | −0.18** (0.00) | −0.18*(0.00) | −0.11* (0.00) | −0.12* (0.00) | −0.12 (0.00) | −0.16* (0.00) | −0.09 (0.00) |

| Chronic stressors | 0.32*** (0.11) | 0.17*** (0.10) | ||||||

| Daily discrimination | 0.34*** (0.73) | 0.15** (0.68) | ||||||

| Family support | −0.48*** (0.89) | −0.29*** (0.91) | ||||||

| Mastery | 0.38*** (0.49) | −0.17** (0.50) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.39*** (1.07) | 0.17** (1.11) | ||||||

| Separateda | 0.18** (2.58) | 0.12* (2.08) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.42 |

| BIC | 1,724.78 | 1,702.15 | 1,699.09 | 1,663.98 | 1,691.09 | 1,689.79 | 1,721.58 | 1,630.25 |

| AIC | 1,717.75 | 1,691.61 | 1,688.55 | 1,653.44 | 1,680.55 | 1,679.25 | 1,711.04 | 1,602.14 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Neighborhood income | −0.17** (0.00) | −0.18** (0.00) | −0.18*(0.00) | −0.11* (0.00) | −0.12* (0.00) | −0.12 (0.00) | −0.16* (0.00) | −0.09 (0.00) |

| Chronic stressors | 0.32*** (0.11) | 0.17*** (0.10) | ||||||

| Daily discrimination | 0.34*** (0.73) | 0.15** (0.68) | ||||||

| Family support | −0.48*** (0.89) | −0.29*** (0.91) | ||||||

| Mastery | 0.38*** (0.49) | −0.17** (0.50) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.39*** (1.07) | 0.17** (1.11) | ||||||

| Separateda | 0.18** (2.58) | 0.12* (2.08) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.42 |

| BIC | 1,724.78 | 1,702.15 | 1,699.09 | 1,663.98 | 1,691.09 | 1,689.79 | 1,721.58 | 1,630.25 |

| AIC | 1,717.75 | 1,691.61 | 1,688.55 | 1,653.44 | 1,680.55 | 1,679.25 | 1,711.04 | 1,602.14 |

Note: N = 248. Standardized coefficients shown with standard errors in (). AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion.

aReference is all other marital statuses.

*p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Stress Process Variables (Mediation)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Neighborhood income | −0.17** (0.00) | −0.18** (0.00) | −0.18*(0.00) | −0.11* (0.00) | −0.12* (0.00) | −0.12 (0.00) | −0.16* (0.00) | −0.09 (0.00) |

| Chronic stressors | 0.32*** (0.11) | 0.17*** (0.10) | ||||||

| Daily discrimination | 0.34*** (0.73) | 0.15** (0.68) | ||||||

| Family support | −0.48*** (0.89) | −0.29*** (0.91) | ||||||

| Mastery | 0.38*** (0.49) | −0.17** (0.50) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.39*** (1.07) | 0.17** (1.11) | ||||||

| Separateda | 0.18** (2.58) | 0.12* (2.08) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.42 |

| BIC | 1,724.78 | 1,702.15 | 1,699.09 | 1,663.98 | 1,691.09 | 1,689.79 | 1,721.58 | 1,630.25 |

| AIC | 1,717.75 | 1,691.61 | 1,688.55 | 1,653.44 | 1,680.55 | 1,679.25 | 1,711.04 | 1,602.14 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Neighborhood income | −0.17** (0.00) | −0.18** (0.00) | −0.18*(0.00) | −0.11* (0.00) | −0.12* (0.00) | −0.12 (0.00) | −0.16* (0.00) | −0.09 (0.00) |

| Chronic stressors | 0.32*** (0.11) | 0.17*** (0.10) | ||||||

| Daily discrimination | 0.34*** (0.73) | 0.15** (0.68) | ||||||

| Family support | −0.48*** (0.89) | −0.29*** (0.91) | ||||||

| Mastery | 0.38*** (0.49) | −0.17** (0.50) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.39*** (1.07) | 0.17** (1.11) | ||||||

| Separateda | 0.18** (2.58) | 0.12* (2.08) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.42 |

| BIC | 1,724.78 | 1,702.15 | 1,699.09 | 1,663.98 | 1,691.09 | 1,689.79 | 1,721.58 | 1,630.25 |

| AIC | 1,717.75 | 1,691.61 | 1,688.55 | 1,653.44 | 1,680.55 | 1,679.25 | 1,711.04 | 1,602.14 |

Note: N = 248. Standardized coefficients shown with standard errors in (). AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion.

aReference is all other marital statuses.

*p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Coping Resource × Social Stress Interactions (Moderation)

| b (SE) | |

| Model 1: Family Support × Chronic Stressors | −0.42 (0.21)* |

| Model 2: Family Support × Daily Discrimination | −2.39 (1.19)* |

| Model 3: Mastery × Chronic Stressors | −0.13 (0.11) |

| Model 4: Mastery × Daily Discrimination | −1.13 (0.79) |

| Model 5: Self-Esteem × Chronic Stressors | 0.16 (0.29) |

| Model 6: Self-Esteem × Daily Discrimination | −0.62 (1.85) |

| b (SE) | |

| Model 1: Family Support × Chronic Stressors | −0.42 (0.21)* |

| Model 2: Family Support × Daily Discrimination | −2.39 (1.19)* |

| Model 3: Mastery × Chronic Stressors | −0.13 (0.11) |

| Model 4: Mastery × Daily Discrimination | −1.13 (0.79) |

| Model 5: Self-Esteem × Chronic Stressors | 0.16 (0.29) |

| Model 6: Self-Esteem × Daily Discrimination | −0.62 (1.85) |

Note: N = 248. Unstandardized coefficients shown with standard errors in (). All first-ordered terms are included in the respective models.

*p ≤ .05.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Coping Resource × Social Stress Interactions (Moderation)

| b (SE) | |

| Model 1: Family Support × Chronic Stressors | −0.42 (0.21)* |

| Model 2: Family Support × Daily Discrimination | −2.39 (1.19)* |

| Model 3: Mastery × Chronic Stressors | −0.13 (0.11) |

| Model 4: Mastery × Daily Discrimination | −1.13 (0.79) |

| Model 5: Self-Esteem × Chronic Stressors | 0.16 (0.29) |

| Model 6: Self-Esteem × Daily Discrimination | −0.62 (1.85) |

| b (SE) | |

| Model 1: Family Support × Chronic Stressors | −0.42 (0.21)* |

| Model 2: Family Support × Daily Discrimination | −2.39 (1.19)* |

| Model 3: Mastery × Chronic Stressors | −0.13 (0.11) |

| Model 4: Mastery × Daily Discrimination | −1.13 (0.79) |

| Model 5: Self-Esteem × Chronic Stressors | 0.16 (0.29) |

| Model 6: Self-Esteem × Daily Discrimination | −0.62 (1.85) |

Note: N = 248. Unstandardized coefficients shown with standard errors in (). All first-ordered terms are included in the respective models.

*p ≤ .05.

Although median household income was measured at the neighborhood-level, it is appropriate to treat this variable as an individual-level variable because most respondents reside in different neighborhoods and, as such, multilevel models were not necessary. To arrive at the final models presented in Table 2, we used an iterative forward-backward stepwise procedure until the most appropriate model was determined via Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) and BIC statistics. Based on this procedure, several variables were excluded from the final models, which include: age, disability status, individual SES, recent life events, and friend support. This procedure also indicated that the most parsimonious model involved collapsing widowed, divorced, never married, and married into one category, with “separated” as the reference group.

Results

Descriptives

As shown in Table 1, African American men report a mean of 7.89 depressive symptoms (past month), with approximately 11% reporting 16 or more symptoms. The average (mean) of median household income at the neighborhood level is $34,409.84 (median average = $32,868). The average number of chronic stressors was 3.31 (SD = 4.21, range = 0–26) and recent life events was 1.05 (SD = 1.53, range 0–9). The mean friend and family support was 3.36 and 3.63 and, respectively, which fall between “moderately” and “very” supportive. The average score for self-esteem was 2.88 (SD = 0.92, range = 0.29–4.00) and mastery was 3.76 (SD = 0.42, range = 1.67–4.00). Based on the oversampling of persons with a physical disability, approximately one-third of the sample reports a physical disability (32.66%). The majority of respondents were currently married (58.87%), with an average age of 58.11 years (SD = 16.26, range = 18–86).

Multivariable—Mediation

In Table 2, standardized coefficients from OLS regressions are presented to assess the (relative) strength of the association between the SPM variables and depressive symptoms. Model 1 indicates that a one standard deviation increase in neighborhood level income is associated with a 0.17SD decrease in depressive symptoms (SE = 0.00, p ≤ .01). Models 2–7 step in each covariate separately to assess their contribution for depressive symptoms, as well as their mediating effects between neighborhood income and depressive symptoms. When entered individually, family support has the strongest correlation with depressive symptoms (β = −0.48, SE = 0.89, p ≤ .001), explaining approximately one-quarter of the variability in depressive symptoms (R2=.26).

For the most part, the association between neighborhood income and depressive symptoms is robust to additional covariates, underscoring its significance for the psychological health of African American men. One exception, when self-esteem is included, the association between neighborhood income and depressive symptoms is reduced to nonsignificance (β = −0.12, SE = .00, p ≤ .051). Comparing Models 1 and 4, mediation analysis reveals a significant reduction (29%) in the neighborhood income coefficient after controlling for self-esteem (Sobel: z = −2.12, p = .03). Mastery also significantly mediates the relationship between neighborhood income and depressive symptoms (32%, z = 2.12, p = .03).

Reflecting conceptual Figures 1a and b, results in Model 8 indicate that both measures of stress and each coping resource are independently associated depressive symptoms. Collectively, comparing Models 1 and 8, stress exposure (chronic stressors and discrimination) and coping resources (family support, mastery, and self-esteem) explain approximately half (47%) of the relationship between neighborhood SES and depressive symptoms. In addition, almost half of depressive symptoms are explained by the full model (R2 = 42%).

Multivariable—Moderation

Table 3 presents interaction results, with all six models including the first-ordered terms that make up each interaction term (not shown). Reflecting conceptual Figure 1c, findings indicate that perceived family support significantly buffers the negative mental health consequences of stress exposure. Specifically, increased depressive symptoms associated with higher levels of chronic stressors (and daily discrimination) are relatively lower among African American men who report more family support.

Discussion

Approximately 11% of African American men reported 16 or more symptoms, a cutoff often used as a proxy estimate for clinical-level depression (Lewinsohn et al., 1997). Although larger than the 6.37% recently reported in a national sample of African American men (Lincoln et al., 2011), this difference may stem from the shortened 12-item scale used by Lincoln and colleagues. It should also be noted that depressive symptoms among African American men may be underreported due to gendered differences in the expression of depression (Watkins, Abelson, & Jefferson, 2013). Nevertheless, the findings underscore the importance of research identifying risk/protective factors for depressive symptoms among African American men (Ward & Mengesha, 2013).

Consistent with prior research of African American men (Hoard & Anderson, 2004; Kogan & Brody, 2010), individual SES was not associated with depressive symptoms. This has led some researchers to conclude that SES may not be as important for mental health, as well as physical health (see Turner, Brown, & Hale, 2017), among African Americans compared to Whites. Individual-level SES may be less likely to contribute to the well-being of African American men compared to others, due to the often-unrealized rewards associated with higher income and education among African Americans, such as residing in safe and desirable neighborhoods (Williams, 2003). However, we found those residing in lower SES neighborhoods experienced significantly more depressive symptoms, underscoring the significance of neighborhood-level SES for the psychological health of African American men. Thus, it is important to include neighborhood SES in research examining the role of SES for mental and physical health among African American men.

Residing in low-income neighborhoods may not only increase risk for poor mental health due to high rates of crime, poverty, and unemployment (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001) but living in such contexts may also indirectly translate into more depressive symptoms due to fewer psychosocial coping resources. A strong sense of mastery and self-esteem are recognized as important factors for the psychological well-being of African American men (Watkins, 2012). Indeed, consistent with prior research (Weaver & Gary, 1994), we found that mastery and self-esteem play an important role in mitigating the negative psychological harm associated with lower-income neighborhoods. The findings highlight the significance of intrapersonal coping for the psychological health of African American men (Weaver & Gary, 1994), whereby self-reliance is an important coping strategy of African American men (Ellis, Griffith, Allen, Thorpe, & Bruce, 2015; Hammond, 2012).

Although intra-personal coping may be important in the link between neighborhood SES and depressive symptoms, our findings revealed that when coping with social stress, it was perceived family support, rather than mastery and self-esteem, that moderated the negative mental health consequences of social stress. Specifically, increased depressive symptoms linked to greater chronic stressors and daily discrimination were relatively lower among those reporting more family support. Building on prior research highlighting that social support is important for the mental health of African American men (Hoard & Anderson, 2004; Kogan & Brody, 2010; Watkins, 2012), this study demonstrates the importance of perceived family support for buffering the deleterious mental health effects of stress exposure among African American men. Thus, while self-reliance through mastery and self-esteem may be important for mitigating the psychological consequences associated with residing in relatively poor neighborhoods, the ability to perceive support from one’s family is important for minimizing the negative mental health consequences of stress exposure for African American men. In addition to the importance of African American men’s involvement (and presence) for families (Baker, 2013), our findings highlight the mental health significance perceived family support for African American men managing stress exposure.

African American men are at increased risk for chronic stressors and daily discrimination (Williams, 2003). Griffith and colleagues (2013) highlight the importance of chronic stressors associated with home and work for the health of African American men. Although we did not find that social stress mediated the SES—depressive symptom relationship, which is consistent with prior research (Weaver & Gary, 1994), both chronic stressors and daily discrimination independently contributed to depressive symptoms among African American men, underscoring the importance of addressing everyday hardships to address the psychological well-being of African American men.

There are a few noteworthy limitations. First, given the localized nature of the sample, it is unclear whether the results are generalizable to other U.S. locales. However, the fact that many of the patterns in this study are consistent with prior research in various locales, including the level of depressive symptoms among African American men, the concern of generalizability is somewhat tempered. Second, as with any cross-sectional study, neither temporality nor causality can be determined. Given that the relationships between SES, stress exposure, coping resources, and mental health are likely reciprocal in nature, longitudinal studies are needed to better understanding the temporal order of SPM variables among African American men.

Conclusion

Given that African American men are disproportionately more likely than their White counterparts to reside in lower-income neighborhoods (Massey & Denton, 1993), public health policies aimed at addressing poor mental health among African American men should account for neighborhood conditions. Indeed, individual-level SES, stress exposure, and coping resources among African American men must be situated within broader economic and sociopolitical contexts (Enyia, Watkins, & Williams, 2016). Within this broader contextual framework, social stress and psychosocial resources play an important role in understanding depressive symptoms among African American men. On the one hand, mastery and self-esteem serve as linking mechanisms between neighborhood SES and depressive symptoms and, on the other hand, perceived family support serves as a buffer for chronic stressors and daily discrimination. Collectively these factors explain nearly half the variability in depressive symptoms, underscoring the utility of the stress process model for understanding the psychological well-being of African American men.

Funding

This study was supported by grant R01DA13292 to R. Jay Turner from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References