-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

William C. Hunter, Susan E. Elswick, J. Helen Perkins, JoDell R. Heroux, Helene Harte, Literacy Workshops: School Social Workers Enhancing Educational Connections between Educators, Early Childhood Students, and Families, Children & Schools, Volume 39, Issue 3, July 2017, Pages 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx009

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Parents and family members play an essential role in the literacy development of their children. Research indicates that children with disabilities enrolled in early childhood programs are likely to experience marginalization in terms of receiving educational services. This research emphasizes the importance of exposing students with disabilities enrolled in early childhood programs (preK) to literacy-rich home and school environments. School social workers often play an integral part in meeting both educational and behavioral needs of children in schools. Using data collected during a social worker–facilitated Routines-Based Interview, teams of professionals can develop targeted early literacy workshops designed to strengthen the connection between parents and their children's school. The authors conceptualize how an interdisciplinary approach involving the school social worker is essential in developing interactive literacy workshops designed to enhance the development of children's early literacy skills within the home and school environment. The article includes a discussion on the planning stages, reading interventions, sample workshop activities, and actual implementation of the literacy workshop.

Although many acknowledge the importance of early language and literacy development, more than one-third of children in the United States enter school with delays in language and early literacy skills that place them at considerable risk for developing long-term reading difficulties (Neuman, 2006). Students with mild to moderate disabilities and English language learners (ELLs) often have difficulties with many aspects of reading, including oral language comprehension (Tam, Heward, & Heng, 2006), and are considered to be at elevated risk for exhibiting delays in early literacy development (Justice, Logan, Işıtan, & Saçkes, 2016). Although the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-446) promotes early intervention for children with developmental delays, research provides evidence that children from low socioeconomic backgrounds often experience challenges regarding eligibility for special education services (Fujiura & Yamaki, 2000). Manning and Gaudelli (2006) reported that students with disabilities from low socioeconomic backgrounds enrolled in early childhood programs are likely to experience marginalization in terms of receiving educational services.

Professionals in the field of education understand that young children are developing and learning in the family context and that services and supports targeting parents and caregivers are beneficial in strengthening early literacy experiences (Bruder, 2010; Dunst, 2007; Dunst, Valentine, Raab, & Hamby, 2013). Discipline-specific professionals should provide services designed to address academic, social, and behavioral domains, through a team approach (Campbell & Sawyer, 2007). For this reason, services promoting the development of early literacy skills for preK students with disabilities would be more effective using a team approach that involves the family and various educational professionals (DeVore, Miolo, & Hader, 2011).

Essential literacy skills for young children, ages four and five, include knowledge of print, phonological awareness, and oral language comprehension (Jennings, Caldwell, & Lerner, 2010). Development of literacy skills necessitates rich language interactions and experiences throughout the day (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009). Educational professionals such as general and special education teachers, school social workers, speech and language pathologists, as well as parents and family members, play critical roles in the development of preschool-age children with and without disabilities (DeVore et al., 2011). At the preschool level, school social workers may provide consultative services to classroom teachers or direct services to children; they are also instrumental in communicating with and supporting parents and families (Alameda-Lawson, Lawson, & Lawson, 2010). The NASW Standards for School Social Work Services (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2012) focuses on the importance of cultural competence, interdisciplinary leadership, and collaboration within the school setting. These are critical skills for providing quality social work services both in the school setting and with families (Johnston, McDonnell, & Hawken, 2008). For this reason, school social workers should be part of an interdisciplinary approach by collaborating with families and collecting information that would support the development of targeted, routine-oriented, early literacy workshops (Couturier, Gagnon, Carrier, & Etheridge, 2008).

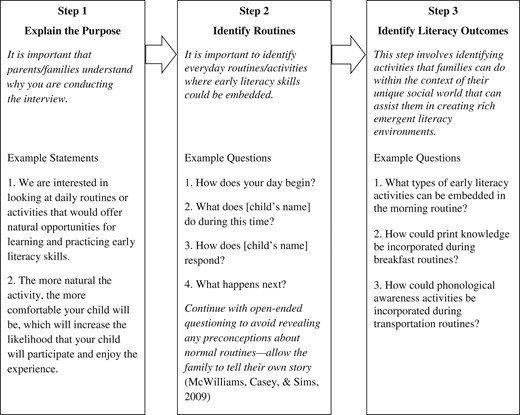

The special education team approach capitalizes on the specific knowledge and skills of its members (Shepherd & Linn, 2015). This approach facilitates successful development and implementation of a comprehensive literacy workshop for parents and families to support their child's early literacy development (Jennings et al., 2010). These workshops facilitate authentic school–family partnerships and support respectful alliances grounded in relationship building and dialogue (Henderson, Mapp, Johnson, & Davies, 2007; Pushor, 2010). Working with an interdisciplinary team of educators, school social workers could administer a Routines-Based Interview (RBI) to gather information that can be used within literacy workshops (McWilliam, Casey, & Sims, 2009). The RBI, as implemented by early interventionists, is a semistructured interview with three purposes: (1) to develop a list of functional outcomes, (2) to assess child and family functioning, and (3) to establish a positive relationship with the family (DeVore et al., 2011; McWilliam et al., 2009). This article provides a framework for an interdisciplinary literacy workshop that supports families in the development of their children's early literacy skills and strengthens the home–school connection. This article also features a case scenario and implications for research.

Development of Children's Literacy within the Home

Research indicates that when preK children with disabilities are in structured, literacy-rich environments they demonstrate growth in the development of emergent early literacy skills (Dennis, Lynch, & Stockall, 2012). The diverse nature of home environments (for example, family education, literacy habits, and income) may influence the development of children's early literacy skills (Bruns & Pierce, 2007). Factors such as low income and disability influence students’ family level of participation in educational activities (Al Otaiba, Lewis, Whalon, Dyrlund, & McKenzie, 2009; DesJardin & Ambrose, 2010; Jordan, Miller, & Riley, 2011). Barnyek and McNelly (2009) reported a correlation between teachers’ practices and beliefs about parent involvement and the level of parental and family involvement in at-home educational activities. Therefore, when educators perceive parents and families as disinterested in their child's education, they are less likely to attempt to establish, maintain, and strengthen the home–school connection (Barnyek & McNelly, 2009). School social workers can assist educators with building better parent–teacher relationships and creating a more collaborative approach to learning that results in positive outcomes for young children (Johnston et al., 2008). Based on the NASW Standards for School Social Work Services (NASW, 2012), school social workers should assist in creating better parent–teacher relationships in a variety of ways. Some activities include participating in student support meetings as an advocate, conducting home visits to support the family with identified needs (both educational and behavioral), providing behavioral expertise and supports through behavior intervention plan creation, and parent training opportunities for the families (NASW, 2012).

It is important to acknowledge that families have specialized knowledge and skills that help them successfully navigate their environments (Zeece, 2005), and school social workers are often the catalyst for bridging the school and home environments (Blitz, 2013). School social workers have training in therapeutic interviewing practices that will aid in establishing rapport with parents while also addressing identified family and individual needs. One effective interviewing strategy used by social work practitioners is Motivational Interviewing (MI) (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). MI is an evidence-based intervention used to help individuals and families identify and change behaviors that may be placing them at risk (Sheldon, 2010). The implementation of MI techniques would enhance the school social worker–facilitated RBI process because MI is more effective than traditional information gathering in other settings (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). This blended interview strategy would be useful in collecting the necessary data to develop specific, targeted early literacy activities embedded in everyday family routines.

The Council for Exceptional Children's Division for Early Childhood (DEC) recommends that practices focus on using a family-centered approach that includes building trusting relationships and enhancing knowledge and skills. Collaboration with families requires responsiveness to the concerns, preferences, priorities, cultural and linguistic diversity, and socioeconomic status of families (DEC, 2014). The integration of school social work practice should be at the heart of family-centered approaches in education (Dunst & Trivette, 2009). School social workers receive training in culturally competent practices, identifying needs and strengths, and empowering all parties to work collaboratively toward a common positive goal (Lee, 2007).

Offering workshops aimed at embedding early literacy activities within typical family routines using authentic materials (Jennings et al., 2010) is one method for strengthening the home–school connection. One of the main goals of the literacy workshop is to design and share activities that capitalize on many of the language and literacy activities that naturally occur in the home environment (Carter, Chard, & Pool, 2009). We recommend that the school social worker administer the RBI to obtain specific information for use in developing early literacy workshops. The school social work–implemented RBI process will use aspects of MI with open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summary statements to increase family self-efficacy (Sheldon, 2010). Information gained through the RBI process provides the foundation for planning an interactive literacy workshop designed to support families in developing literacy-rich environments through everyday routines.

Planning and Implementing an Interactive Literacy Workshop

Planning Considerations

The social and cultural contexts in which young children live influence language and literacy opportunities (Carter et al., 2009); therefore, it is critical that individual family routines are identified so workshops can reflect the unique needs of the families involved. School social workers have strategies for engaging parents and families in critical dialogue on various topics and often create an atmosphere of trust and sharing that is necessary for conducting the RBI (McWilliam et al., 2009). The RBI tool is historically used by speech pathologists and other early interventionists in practice; however, having a school social worker implement the RBI assists in enhancing the ability to use the tool from an ecological framework (Wilcox & Woods, 2011). The school social work–directed interview would lead educators toward identifying possible barriers to literacy that may be more psychosocial, familial, or environmental in nature (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Pennekamp & Freeman, 1988). After the identification of potential barriers and client strengths, school social workers will have the opportunity to use their skills and techniques to connect with families in a manner that enhances the school–home relationship and parent engagement (Joseph-Goldfarb, 2014).

Although professionals most often use the RBI to assist in the development of individualized family service plans for infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children with disabilities, the strategy is beneficial for planning and implementing workshops for preschool-age children within their respective schools (Boavida, Aguiar, & McWilliam, 2014). In preparation for the literacy workshop, the multistep RBI process (McWilliam et al., 2009) would be adapted for use with parents and families of children in preK who exhibit delays in critical early literacy skills and who are interested in supporting their children's literacy development at home. The school social worker would adapt the RBI to focus on gathering critical information about children's everyday routines and identifying specific literacy outcomes.

The questions asked in the interview will include both behavioral and academic concerns that may be negatively influencing the student's success in literacy (DeVore et al., 2011). Identifying these needs will assist the school social worker with direct practice needs of each family (Alameda-Lawson et al., 2010). For example, if the interview yields that a family struggles with their child's behavior in the home, especially related to academics and reading, the school social worker in collaboration with the special education teacher could provide behavioral interventions that would make reading time more focused and effective (Shepherd & Linn, 2015). A potential outcome of the school social worker collecting the RBI data before planning the workshops is that it allows the team to tailor the workshops to parent and family needs (Joseph-Goldfarb, 2014). Figure 1 provides steps involved in conducting an RBI.

Literacy Workshop Planning

In terms of planning for the educational interventions of literacy workshops, one consideration is to provide strategies based on kindergarten common core standards (Common Core State Standards Initiative [CCSSI], 2010). Although some students may be under kindergarten age, using kindergarten common core standards will assist with readiness for reading and math through differentiated instruction (Morgan et al., 2013). In terms of the planning team, the special education teacher or the general education teacher can lead this area of the literacy workshop implementation. Examples of educational topics that can be discussed within a literacy workshop are (a) regular practice with complex text; (b) reading, writing, and speaking activities grounded in text evidence; (c) building knowledge through increased exposure to informational (that is, expository) text; and (d) overall comprehension of the text (Liebling & Meltzer, 2011). Readers of all ages must be aware of text structures if they are to be most successful (Meyer, 2003). See Table 1 for examples of reading strategies to assist students in their practice with text structures. In terms of the overall planning of a literacy workshop, collaboration is essential.

Reading Strategies That Can Be Used at Home, Presented by Teacher Representatives of Teacher/Parent Collaborative Council

| Example Strategies All Students |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for Students with Disabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for English Language Learners |

|

|

|

|

| Example Strategies All Students |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for Students with Disabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for English Language Learners |

|

|

|

|

Reading Strategies That Can Be Used at Home, Presented by Teacher Representatives of Teacher/Parent Collaborative Council

| Example Strategies All Students |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for Students with Disabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for English Language Learners |

|

|

|

|

| Example Strategies All Students |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for Students with Disabilities |

|

|

|

|

| Specific Strategies for English Language Learners |

|

|

|

|

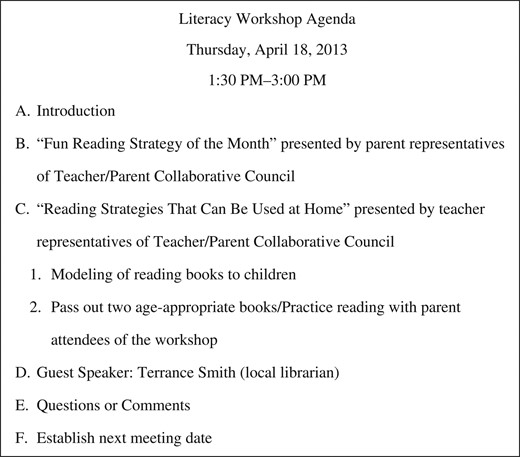

The presenting team of school social workers, educators, and parent representatives should meet and discuss the date and time, notification methods (flyers, radio or television announcements, phone calls) of the workshop, and the best venue for the actual workshop (Come & Fredericks, 1995). The team should also develop an agenda for the literacy workshop (see Figure 2 for an example) (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). Once the planning process is complete, the team can move forward with implementation of the literacy workshop.

Literacy Workshop Implementation

It is suggested that the literacy workshop last approximately 90 minutes (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). At the opening of the workshop, presenters (educators, school social workers, or parent representatives) should acknowledge parents, caregivers, grandparents, and guardians for their efforts in working with their children (Come & Fredericks, 1995). The next step is for presenters to discuss the agenda for the literacy workshop (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). Next, workshop leaders should review the purpose of the RBIs and how that data informed development of the workshop (Boavida et al., 2014). As an example in terms of the intervention within the literacy workshop, the special education or general education teacher can lead strategies focusing on analyzing the structure of a text. This intervention connects with the following standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.K.5 “Identify the front cover, back cover, and title page of a book.”

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.K.6 “Name the author and illustrator of a text and define the role of each in presenting the ideas or information in a text”(CCSSI, 2010).

Before providing strategies for embedding early literacy skills into specific everyday routines, the presenters should provide a few literacy best practices such as how to help children practice holding books correctly and turning pages (Sénéchal & Young, 2008). According to Johnston et al. (2008), additional literacy best practices include the following:

showing children that text in books begins at the top left corner of the page and reads from left to right

pointing to print while reading aloud to teach children that print, not only pictures, tells the story

asking children to retell or act out stories with puppets, costumes, and other props

asking children to predict story outcomes

rereading stories to children.

These are some examples of many early literacy strategies provided through literacy workshops designed to assist parents and caregivers in helping their children develop foundational literacy skills. Table 1 provides strategies for discussion within the literacy workshop for all students, including students with disabilities and ELLs (Dennis et al., 2012). An example in Table 1 that supports information within the kindergarten standards of CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.K.5 includes the following: “Discuss the title and what might happen in the story” (CCSSI, 2010). Children with disabilities often benefit from explicit instruction in literacy skills that appear to be acquired through participation in and repetition of the activity (Bruns & Pierce, 2007). For example, some children develop book knowledge and print awareness from their observation of and participation in read-aloud activities, whereas other children may need explicit instruction to develop these skills (Al Otaiba et al., 2009).

After the initial presentation of literacy strategies, focusing on specific early literacy strategies embedded within everyday routines is a consideration (Sénéchal & Young, 2008). During the embedded literacy strategy component of the workshop, parents and families receive opportunities to create materials using familiar household objects that promote literacy within the home (Sénéchal & Young, 2008). Within the workshop, the interdisciplinary team can recommend that parents encourage their children to write, providing reading materials (Reutzel & Cooter, 2012). Table 2 provides author recommendations for embedding several literacy strategies within the breakfast routine.

Embedding Literacy Activities within the Breakfast Routine

| Strategy . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Print awareness |

|

| Phonological awareness |

|

| Oral language comprehension |

|

| Strategy . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Print awareness |

|

| Phonological awareness |

|

| Oral language comprehension |

|

Note: These are examples of strategies that would be shared at a workshop to capitalize on everyday routines by embedding critical literacy skills for children with and without disabilities in preK.

Embedding Literacy Activities within the Breakfast Routine

| Strategy . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Print awareness |

|

| Phonological awareness |

|

| Oral language comprehension |

|

| Strategy . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Print awareness |

|

| Phonological awareness |

|

| Oral language comprehension |

|

Note: These are examples of strategies that would be shared at a workshop to capitalize on everyday routines by embedding critical literacy skills for children with and without disabilities in preK.

At the end of the workshop, having the facilitators distribute preK books to the participating parents is a consideration (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). “To evaluate the effectiveness of the workshop, questionnaires should be given to the parents/caregivers requesting demographic information and information associated with book reading, number of books, and library visits” (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005, p. 265). The team should develop subsequent workshops based on other common routines that emerged from the RBI data collected.

Case Study

Madison is a first-year early childhood special education teacher at a Head Start early childhood school located in a large urban area. Three of the students in Madison's classroom have developmental delays, and four students receive speech services twice a week for 30 minutes. Based on instructional activities, Madison noticed that several students, including the students with disabilities, are not mastering preliteracy skills.

Madison thought that involving families would increase the children's interaction with literacy within the school and home environment but struggled with how to reach out to families in an authentic way. After careful consideration, she approached the school social worker, Jackie, with an idea to enhance early literacy learning at home through the development and implementation of a family workshop. They reached out to members of the school's parent committee and began brainstorming potential workshop opportunities.

Based on the information from the RBI gathered by Jackie, the team of Madison, Jackie, and the two parent representatives planned a literacy workshop. Based on findings from Jackie's work with the families, workshop times after 6:00 p.m. would work best. Madison had flyers about the literacy workshop at the child sign-out desk and sent correspondences home with her students. In addition, Jackie made home visits to encourage parent participation in the literacy workshops. Madison and her team were delighted that 18 parents attended the session. The team, led by Madison, facilitated the workshop and discussed topics such as age-appropriate book selection, comprehension techniques parents can use, writing materials, and designating specific family reading and writing times. All parents in attendance received two preK books with picture cues and a proportioned number of visuals to words. The team administered a nine-item questionnaire with multiple choice and open-ended questions at the end of the workshop. Parents believed the workshop was effective overall.

Subsequent Literacy Workshops and Additional Resources

One recommendation for subsequent workshops is that parents have the opportunity to share their successes and challenges related to implementation of the literacy strategies presented at previous workshops (Come & Fredericks, 1995). This process will assist with the self-efficacy of the parents introducing and implementing literacy strategies within the home (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). Additional supports could extend learning for parents. Connecting parents and families with the local librarian is beneficial as library staff is suited to help parents and children with literacy activities (Ghoting & Martin-Diaz, 2006). Presenters could invite guest speakers with expertise in literacy from the community and local universities (Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). If presenters are unable to attend the meeting, Skype, Google Hangouts, GoToMeeting, or other virtual options would also allow them to provide parents the necessary information within the workshop (Hunter, Jasper, & Williamson, 2014).

In addition, school social workers can provide other services such as spearheading efforts to secure donated books or specific educational grants for enhancing literacy in early childhood education. One example of a literacy grant program is the First Book organization. First Book (2014) provides educational institutions with free books to disperse in conjunction with literacy activities sponsored by the school.

Concluding Thoughts

Research has shown improvement in literacy skills and overall academic performance from continuing education of children and their parents through planned child–parent interactions (Chance, 2010). Literacy workshops provide parents an opportunity to learn literacy strategies from educators to support their children at home and to share positive literacy experiences they have engaged in with their children (Ghoting & Martin-Diaz, 2006; Jennings et al., 2010). Through the described interdisciplinary approach, literacy workshops have the potential to not only improve academic outcomes of children with developmental delays, but also enhance the parent–school relationship (Barnyek & McNelly, 2009).

Implications for Research

Based on our review of the literature, there is a need for interdisciplinary (connecting social work and education) research to determine the effects of parent literacy workshops on the educational outcomes for students with and without disabilities in preK settings. We also recommend an interdisciplinary examination of the impact of literacy workshops on the parent involvement in a school or school system. A qualitative study examining the experiences of the interdisciplinary team members throughout this process could inform the development of future early literacy projects. The literacy workshop may be a forum for educators to elaborate on the process of developing reading objectives for students with individual education programs. This workshop model opens the door to other possibilities, such as strategies for embedding math and science skills within everyday routines, which would be beneficial for supporting students with disabilities and ELLs in other content areas.

Summary

School social workers often serve as liaisons between school and home environments (Joseph-Goldfarb, 2014). The literacy workshop provides an opportunity for special and general education teachers to team with school social workers to provide academic interventions and create partnerships with families of students (Jennings et al., 2010). School social workers’ ability to enhance family engagement in educational programming will increase the likelihood that families will use applicable interventions during the literacy workshops and in the home environment. The RBI is a critical component to the development of workshops designed to meet the specific needs of the families involved. The school social workers’ participation in the RBI process facilitates the initial gathering of information from parents. The data collected inform meaningful literacy activities during existing routines while building on strengths and identifying family needs. This ability to assist families in enhancing school engagement benefits the assessment and intervention phases of literacy programming. In addition, school social workers are familiar working within an ecological framework, which assists in ensuring successful outcomes across multiple settings and systems (Pardeck, 1988).

References

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, P.L. 108-446, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1400 et seq.