-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Simon Bell, Kirsty Harkness, J. M. Dickson, Daniel Blackburn, A diagnosis for £55: what is the cost of government initiatives in dementia case finding, Age and Ageing, Volume 44, Issue 2, March 2015, Pages 344–345, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu205

Close - Share Icon Share

Sir,

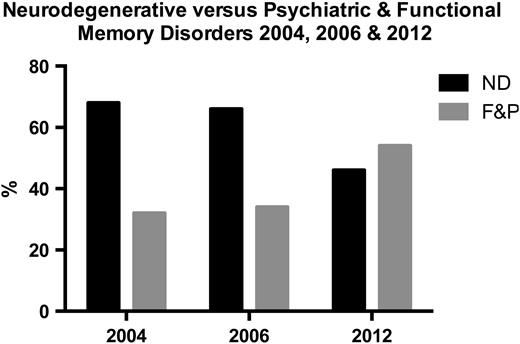

The incentivisation of General Practitioners (GPs) to diagnose dementia began in 2011 with updated dementia strategy. This policy has become more explicit, with the aim to meet the Prime Minister David Cameron's pledge to increase the rates of dementia diagnoses from 48 to 67% by April 2015. The department of health has produced a £55 monetary incentive for GP practices to diagnosis dementia. We do not believe that this strategy will have the desired effect in reducing the dementia gap because of increased referrals of people with cognitive complaints not due to neurodegenerative dementia. This creates a risk of false-positive diagnosis [1], which can have a devastating consequence if incorrectly given a label of dementia We have compared the current case mix attending the Sheffield neurology memory clinic from October 2012 to December 2013 to two previous service evaluations in 2004 and 2006 (Figure 1). This showed an increase in proportion of patients with psychiatric (predominantly depression) and also functional memory problems (defined and discussed elsewhere [2, 3], which is in keeping with previous data from Larner et al. [4, 5]).

Displays the percentage of ND and functional and psychiatric patient presentations to the memory clinic in Sheffield. 50 patients were included in 2004, 45 in 2006 and 82 in 2012.

Not only are we concerned about not reducing the memory gap, but the incentivisation of diagnoses of dementia has the potential to make things worse. The dementia diagnosis rate in Sheffield is higher than most (62%), but this creates more follow-up and support for people with dementia. This affect waiting lists in the memory clinics, which have increased. A lot of work and resources have been spent to reduce the wait. We investigated the quality of GP referrals to memory clinics. Seventy-six per cent of GP referrals to our memory clinic included cognitive screens. The screens such as the 6CIT have good sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease to health volunteers who responded to an invitation to help in research on dementia. These tools will not have the same sensitivity and specificity if conducted on people who attend GPs with cognitive complaints, as this population will likely include many with functional memory disorder and due to depression. GPs are asked to exclude reversible causes of dementia. Testing of B12 and folate was high, but mood screening was included in only 26%. Depression is a severe debilitating disorder that is treatable. It is also a common co-morbidity in people with dementia. We suggest that the financial incentivisation of the diagnosis of dementia may not achieve its targets in reducing the dementia gap, will increase the strain on GPs and Memory clinics, which may adversely affect waiting times and the provision of good-quality post-diagnosis care and support for people with dementia and their families.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

To read more Letters or to respond to any Age and Ageing articles, please visit http://bit.ly/AALetters

Comments

We thank Dr Jenkin for his comments.

We agree that it is very difficult to differentiate depression from dementia even with an hour-long appointment and access to detailed brain imaging. We also agree that treating people with depression is vitally important because it is treatable and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality[1]. Whether they are best treated in a memory clinic is open to debate and the pathway for this patient group needs discussion, locally and nationally, between primary and secondary care. This needs to include appropriate level of post-diagnosis support from whichever secondary care clinic is diagnosing people with depression and/or dementia. The demand, availability of resources and volume of referrals from primary to secondary care are the important issue. Strategies to manage demand are few and far between in NHS or other services[6]. The cost of memory clinic assessment is likely to be higher than being referred to a general psychiatrist or psychologist.

It is also important to note that although depression is a common cause of memory complaint approximately 50% of those attending with non- progressive memory problems are not depressed. We have used the terminology, Functional Memory Disorder (FMD) from Schmidtke et al 2008[2]. Functional neurological disorders are an under-recognized and difficult to treat group[3]. Thus, ideally GPs need to recognize dementia, depression causing cognitive complaints and functional memory disorder. Our research has used conversation analysis in the memory clinic to identify markers of FMD versus dementia[4] .

We would not suggest blood testing for reversible conditions should delay referral to memory clinic. Blood tests and even cognitive screening tools may not help distinguish between FMD, dementia and pseudo dementia without more training.

I would agree that this patient population (people with memory complaints) is a neglected area and with increased media and government attention referrals to primary care are likely to increase. A recent paper suggests that memory concerns are common and increasing[5]. Spending money on improved recognition/detection of FMD seems more appropriate and likely to support people with memory complaint of any source rather than incentivizing GPs £55 to diagnose dementia.

We thank Dr Corrado for his letter

We agree that the case mix of our clinic is not due to the £55 incentivisation policy. Our letter is meant to highlight that non-dementia causes of memory problems are common. It can be very difficult to distinguish between dementia, depression and functional memory disorder. We feel that greater training, developing diagnosis pathways; improved awareness and research into treatment for these patients would be a better way to spend resources than incentivizing GPS to diagnose dementia.

We agree that as a neurology memory clinic we are more likely to see atypical cases of dementia and have a higher proportion of people with functional memory disorder. However, we believe that greater awareness of FMD and depressive pseudo dementia is crucial to prevent misdiagnosis. We have no evidence that misdiagnosis is occurring, baring small anecdotal cases. However asymptomatic brain atrophy is common [7] cognitive complaints are common[5]) and this should be an area of concern as being wrongly told you have Alzheimer's disease can result in significant distress. We would be very interested to know if a smaller but significant population is seen in old age psychiatry led memory clinics.

We agree that case-finding people with memory complaints is important whatever the cause. Depressive pseudo dementia can be difficult to treat and have significant morbidity[1]. Also, FMD is a chronic disorder resulting in distress, loss of earnings due to inability to work[2]. The pathway and process of diagnosing this group requires further work. The simplification of the assessment for people with memory complaints with a £55 incentive to diagnose dementia is unlikely to improve this process.

Yours truly, Daniel Blackburn

1. Sachdev, P.S., et al., Pseudodementia twelve years on. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1990. 53(3): p. 254-9. 2. Schmidtke, K., S. Pohlmann, and B. Metternich, The syndrome of functional memory disorder: definition, etiology, and natural course. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2008. 16(12): p. 981-8. 3. Carson, A.J., et al., Patients whom neurologists find difficult to help. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2004. 75(12): p. 1776-8. 4. Jones, D., et al., Conversational assessment in memory clinic encounters: interactional profiling for the differential diagnosis of dementia and functional memory disorder. Aging and Mental Health, 2015. 5. Begum, A., et al., Subjective cognitive complaints across the adult life span: a 14-year analysis of trends and associations using the 1993, 2000 and 2007 English Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys. Psychol Med, 2014. 44(9): p. 1977-87. 6. Blank, L., et al., Referral interventions from primary to specialist care: a systematic review of international evidence. Br J Gen Pract, 2014. 64(629): p. e765-74. 7. Sandeman, E.M., et al., Incidental findings on brain MR imaging in older community-dwelling subjects are common but serious medical consequences are rare: a cohort study. PLoS One, 2013. 8(8): p. e71467.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared

Sir,

Bell et al describe the impact that financial incentivisation has had on referrals to their memory service and I agree that there are many problems with incentivisation as a means of driving improvements in care. For example, it can divert resources into areas of medico-political priority but also away from other important areas of care, to the detriment of the care provided for many patients; actions taken purely in pursuit of an incentive can sometimes conflict with clinical judgement.

However, one potential advantage of the incentive for diagnosing dementia is that it may have resulted in an earlier dementia diagnosis for many people, with the associated benefit of facilitating advance care planning and earlier support for carers. In my opinion, this would go a long way towards justifying the additional workload both in the memory service and in primary care. Certainly in the hospital setting, where approximately 25% of inpatient beds are occupied by people with dementia(Counting the cost: caring for people with dementia on hospital wards - Alzheimer's society, 2009), it is extremely helpful to be able to address future care planning with patients while they are still in the earlier stages of their neuro-degenerative disease.

Although concerns are highlighted that the increasing diagnosis rate has led to pressures in the provision of post diagnosis support, post- diagnosis care is certainly improved for the people who would have remained undiagnosed and had no access to any support at all.

The burden of work relating to dementia is clearly huge for healthcare providers in all settings and throughout the whole course of the illness. I believe that there is an important role for Geriatricians and General Practitioners in developing more integrated services for dementia diagnosis and post-diagnostic support, in collaboration with existing specialists in the memory clinic.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared

The letter by Bell et al makes several important and interesting points however I feel some of the authors' conclusions are a little misleading.

The authors conducted their study on patients attending the Sheffield 'neurology memory clinic' between October 2012 - 2013 (a time well before the GP financial incentive of £55 (referred to in their title) was introduced in October 2014).

The age distribution of their patient cohort is important but not stated. One would assume that as this was a neurology clinic it is likely they were at the 'younger end' of the age spectrum and also more likely to present atypically? Their finding of a high prevalence of functional and mental health problems in their patients may therefore not be representative of patients attending the majority of memory clinics in the UK.

What the authors have demonstrated is that GPs have identified a large number of people with significant problems presenting as "pseudo- dementia", emphasising the importance of excluding depression and mood disorders in any patient presenting with cognitive impairment. Yet only 26% of their cohort had mood screening, surely it is this aspect of their study which should have been given greater emphasis and prominence? It may well be that the 'case finding process' is successfully identifying people with serious health issues but it is their assessment and appropriate referral which is at fault and not the process itself.

Conflict of Interest:

I am the Clinical Lead ('Dementia Champion') for Leeds Teaching Hospitals and the Joint Clinical Lead for the Yorkshire and Humber Strategic Clinical Network for Dementia

Sir, Bell et al report the problems with increasing memory clinic referrals following the financial incentivisation of GPs to make a dementia diagnosis [1]. I share their concern about the impact of financial incentivisation but would query the implication from their letter that they are being sent the 'wrong' patients. The say they are seeing a greater proportion of patients with psychiatric conditions (predominantly depression) and also functional memory problems. I would suggest if this incentivisation of GPs leads to better identification of people with depression this may well be a good thing. Differentiating depression and dementia (especially in the less than 10 minutes allowed in primary care) can be very challenging and obviously dementia and depression can co- exist. It may be that this population of patients with depression or coexistent depression and dementia derives the most benefit from memory clinic. Certainly one could argue that treatment for depression in the elderly is more likely to be effective than treatment of dementia given the very modest benefit shown by current drugs [2]. Either way, rather than being frustrated that the patients arriving at memory clinic don't all have 'pure' dementia shouldn't we design the clinical service to support this? I would also question whether asking GPs to rule out 'reversible causes of dementia' is a good idea at all. The idea of 'reversible dementias' is significantly overemphasised as many examples in the literature have demonstrated: A 2006 community based sample of 560 patients with dementia identified potentially reversible causes in a small number of cases but none of the patients' conditions reversed with treatment [3]. Equally a 2012 study showed only partial reversal in a very modest 1.7% of the patients seen in elderly care clinic with dementia [4]. It would seem far more likely with this as a barrier to referral that a GP mistakes a low serum vitamin b12 as the cause of the dementia and simply delays appropriate referral. I feel the real problem here is an overwhelming demand for assessment. This will be in part due to the government's financial incentivisation but also surely due to the fact that this was a historically profoundly neglected area.

Rodric Jenkin

Whittington Hospital

1. Bell S, Harkness K, Dickson JM, Blackburn D. A diagnosis for ?55: what is the cost of government initiatives in dementia case finding. Age Ageing. 2015 Mar;44(2):344-5

2. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 4;148(5):379-97.

3. Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Cha RH, Edland SD, Rocca WA.Incidence and causes of nondegenerative nonvascular dementia: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2006 Feb;63(2):218-21

4. Muangpaisan W, Petcharat C, Srinonprasert V. Prevalence of potentially reversible conditions in dementia and mild cognitive impairment in a geriatric clinic. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012 Jan;12(1):59- 64

Conflict of Interest:

None declared