-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gerfeson Mendonça, Luanna Alexandra Cheng, Edilânea Nunes Mélo, José Cazuza de Farias Júnior, Physical activity and social support in adolescents: a systematic review, Health Education Research, Volume 29, Issue 5, October 2014, Pages 822–839, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyu017

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The objective of this review was to systematically synthesize the results of original studies on the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents, published until April 2011. Searches were carried out in Adolec, Eric, Lilacs, Medline, SciELO, Scopus, SportsDiscus and Web of Science electronic databases and the reference lists of selected articles. Searches for articles, data extraction and assessment of methodological quality were conducted independently by two reviewers. In total, 75 articles met inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Most studies were published over the past 6 years (2006–11), conducted in high-income countries, with a cross-sectional design, using subjective measures of physical activity (e.g. questionnaires and recall) and exhibited medium to high methodological quality level. Social support was positive and consistently associated with the physical activity level of adolescents in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Those who received more overall social support as well as support from both parents, friends and family showed higher levels of physical activity. It is concluded that social support is an important factor associated with physical activity level in adolescents and should be targeted in intervention programs that aim to increase physical activity levels in this population group.

Introduction

Among the factors associated with physical activity, psychosocial factors such as self-efficacy, attitude and social support are the most widely analyzed and are those that can best explain the variations in physical activity levels in adolescents [1, 2]. Social support is a construct contained in a number of theories (Social Cognitive and Planned Behavior Theory) and models (Health Belief and Social Ecological Model) used to explain physical activity behavior [3]. It is described as an action that helps a person adopt and/or maintain a particular practice that can occur in different ways, such as instrumental/direct (characterized by acquisition or sports equipment sharing, facilitating transport to local practices and engaging in physical activities together), psychological/emotional (transmitted through incentives, words of motivation and encouragement for practices) and instructional/informative support (characterized by acts of orientation, counseling and talks about the importance and appropriate ways of engaging in physical activities) [4–7]. Parents, family members (brothers, uncles and grandparents), friends and teachers have been the most extensively investigated, because they are the main sources of support [4, 5, 7].

There are several systematic reviews on correlates of physical activity in adolescents [1, 2, 8–12], most of which identified social support as a factor positively associated with physical activity in adolescents [1, 2, 8, 9, 12]. However, these reviews clustered the results of the association from various measures and outcomes of physical activity (overall measure; physical activity by domain: leisure, commuting, structured and unstructured sports, among others) with overall scores of sources and types of social support. This procedure does not allow an assessment of how different measures of sources and types of social support are associated with a particular global and specific means of measuring physical activity as well as the simultaneous effect of providing different types of social support. Furthermore, they did not assess the extent to which the association between different types and sources of social support and engaging in physical activity varies as a function of sex, age and methodological quality of the studies.

Studies have shown that the relative importance of different sources and types of social support may vary with the characteristics of the physical activities performed [13, 14]. For example, social support provided by parents is usually in the form of sports equipment, transportation to sporting venues as well as reinforcement and encouragement to engage in leisure-time physical activities [15], whereas friends tend to provide more support by engaging in more vigorous physical activities and competitive sports [16]. There is also evidence that certain types of social support such as engaging in activities with the adolescent are more strongly associated with leisure-time physical activity [17], whereas other types such as encouragement have been important for active commuting [18]. It must also be taken into account that adolescents that perceive various types of social support are more likely to be more physically active, as they are commonly involved in a range of physical activities that require different types of social support [5].

Thus, the objective of this review was to systematically synthesize the results of studies on the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents, considering the different sources and types of social support, the domain and intensity of physical activity as well as its variations by sex and age and the quality of the studies analyzed.

Methods

Searches and study selection

The development of this review followed the guidelines suggested by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [19]. Original articles that analyzed the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents were reviewed. The electronic database, descriptors/terms and logical operators used in searches are described in Table I.

Electronic databases, descriptors/terms and operators used in searches of studies on physical activity and social support in adolescents

| Databases . | Descriptors/termsa . | Operatorsb . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity: physical activity, motor activity, physical exertion, sports, exercise, leisure physical activities, leisure activities, physical exercise and physical inactivity. | And/Or |

| Social support: social support, determinant factors, associated factors and correlated factors. | ||

| Population group: children, adolescent, youth, teen, teenager, high school, students, young, schoolchildren and school children. |

| Databases . | Descriptors/termsa . | Operatorsb . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity: physical activity, motor activity, physical exertion, sports, exercise, leisure physical activities, leisure activities, physical exercise and physical inactivity. | And/Or |

| Social support: social support, determinant factors, associated factors and correlated factors. | ||

| Population group: children, adolescent, youth, teen, teenager, high school, students, young, schoolchildren and school children. |

aDescriptors in English/Portuguese; bCombinations descriptors and terms used.

Electronic databases, descriptors/terms and operators used in searches of studies on physical activity and social support in adolescents

| Databases . | Descriptors/termsa . | Operatorsb . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity: physical activity, motor activity, physical exertion, sports, exercise, leisure physical activities, leisure activities, physical exercise and physical inactivity. | And/Or |

| Social support: social support, determinant factors, associated factors and correlated factors. | ||

| Population group: children, adolescent, youth, teen, teenager, high school, students, young, schoolchildren and school children. |

| Databases . | Descriptors/termsa . | Operatorsb . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity: physical activity, motor activity, physical exertion, sports, exercise, leisure physical activities, leisure activities, physical exercise and physical inactivity. | And/Or |

| Social support: social support, determinant factors, associated factors and correlated factors. | ||

| Population group: children, adolescent, youth, teen, teenager, high school, students, young, schoolchildren and school children. |

aDescriptors in English/Portuguese; bCombinations descriptors and terms used.

The selection of descriptors was based on prior consultation with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS), and specific terms that refer to ‘social support’, ‘physical activity’ and ‘adolescent’. Study selection, data extraction procedures and assessment of article quality were conducted independently by two reviewers (G.M. and L.A.C). In cases of discrepancy, a third reviewer (J.C.F.J.) was consulted and the question was resolved by consensus.

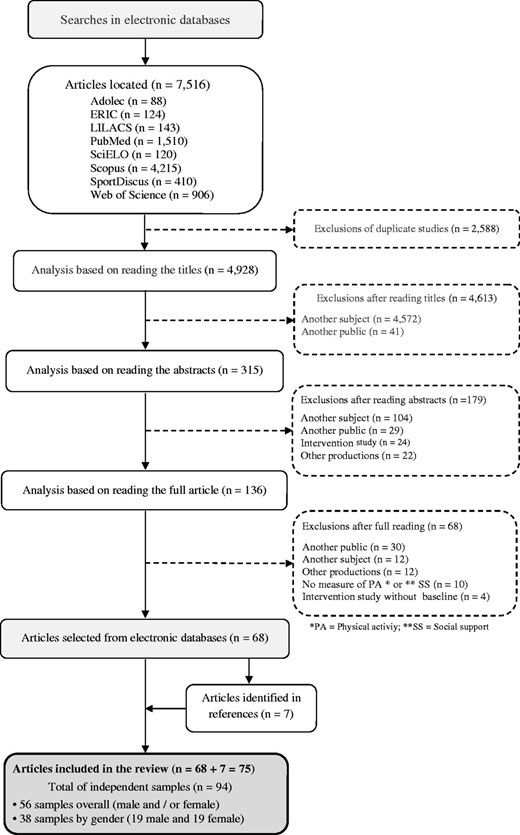

Study selection involved four stages, as described in Fig. 1. The first consisted of reading the article titles. In the second stage, the decision was based on information contained in the abstracts. When these did not contain enough information for decision making as to inclusion or exclusion, the article was kept for the ensuing stages. In the third stage, the articles were fully analyzed. Finally, reference lists of articles selected in the third stage were examined to identify potentially relevant studies that were not identified in the initial selection.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria established were: (i) original article published in Portuguese or English and indexed up to April 2011; (ii) studies with adolescents aged 10–19 years or average age in this range, or those including other ages, but presenting separate results for the age group under analysis; (iii) studies with cross-sectional and longitudinal design and intervention studies if presenting baseline results.

Exclusion criteria were studies that used high performance sport teams as a measure of physical activity, studies on special groups of adolescents (e.g. pregnant, postpartum period and obese), or those with chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease), instrument validation articles and qualitative research. Studies that did not present a summary measure of the association between physical activity and social support and those that used cardiorespiratory fitness as indicator of physical activity level were also excluded.

Definition of terms

Studies on any type of physical activity (structured and unstructured activities, games, plays, dances, recreational sports), irrespective of the domain (leisure, school, commuting, work and home) and method used to measure it (objective and subjective) were considered, as long as they included a summary measure of physical activity (e.g. minutes per month/week/day, frequency of practice, METs, kcal, score). In case of studies that used objective and subjective methods simultaneously to measure physical activity, the results of the former were considered [10].

Any type of social support provided by the following sources was considered: general social support (did not specify the source of social support or combination of different sources in a single measure), parents (father and mother), father only, mother only, friends (including peers and classmates), the family (social support provided by different family members such as parents, uncles, cousins and grandparents combined into a single measure), siblings, teachers, the school and social support characterized as ‘other’ (such as coaches, school environment and other adults).

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed using a previously tested standardized instrument. The following information was extracted: author, year of publication, country of origin of the sample, sample size and selection procedure, study design, characteristics of study participants (age and sex), main statistical analysis used, instruments to measure physical activity and social support, testing of these instruments, domains of physical activity, sources and types of social support measured and the main results of the association between physical activity and social support.

Due to the diversity of statistical techniques used in data analysis, it was decided to gather them into four groups: correlations, analysis of variance or covariance, regression models and structural equation modeling. Whenever possible, results of the multivariate rather than bivariate analysis were used. A total of 97.4% of the results derived from multivariable analyses. Studies that reported results separately for males and females were considered two independent samples, as adopted in other review studies on factors associated with physical activity [1, 11].

Evaluating study quality

A critical assessment of article quality was conducted, particularly in relation to methodological procedures. An instrument was developed based on several recomendations and checklists such as: Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [20], Downs and Black checklist [21] and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [22].

The instrument consisted of 12 items (e.g. adequately described variables, validity and accuracy instruments used to measure outcome, sample size, confounding variables and study limitations), each of which was attributed three response options: nonexistent = 0; partial = 1 and total = 2. A score was then calculated based on the sum total attributed to each item, which ranged from 0 to 24 points. These scores were classified into three levels: level A (high quality): studies that obtained ≥70% of total points (≥16.8 points); level B (medium quality): studies that obtained between 51% and 69% (12.1–16.7 points) and level C (low quality): studies with ≤50% (≤12.0 points). These criteria were adapted from the CONSORT [22]; the adaptation process was similar to that described in other review articles [23–25]. The protocol used for data extraction and assessment of study quality can be obtained by contacting the authors of this study.

Codification and summary of the associations

Due to the diversity of physical activity and social support measuring instruments as well as the statistical analysis used to summarize the results of the associations between physical activity and social support, procedures used by Sallis et al. [12] and van der Horst et al. [1] in their systematic reviews were adopted.

The studies that found statistically significant associations between physical activity and social support were allocated to the ‘related to physical activity’ column and the direction of the association was labeled with ‘+’ for positive association and ‘−’ for negative. Studies that did not find a significant association were allocated to the ‘not related to physical activity’ column and labeled with ‘0’.

The consistency of study results was determined as follows: when ≥60% of the samples in the ‘evidence’ column showed results in the same direction, they were classified as consistent with a positive (‘++’), negative (‘−−’) or nonexistent association (‘00’); between 33% and 59% as inconsistent, represented by ‘+?’, ‘−?’ or ‘0?’; and <33% as inconsistent with no association between physical activity and social support, depicted by a question mark (‘?’).

Evidence showed 50% of samples had association results in the same direction and 50% in another were also classified as inconsistent, illustrated by a double question mark (‘??’), indicating a lack of definition in the direction of evidence (‘+’, ‘−’, ‘0’). The code summaries of evidence were only computed for variables studied in at least three independent samples for each source of social support.

Results

Of the 7523 articles identified in all search strategies (7516 in databases and 7 in the reference lists of articles), 75 met inclusion criteria and were analyzed (Fig. 1). The articles selected were published between 1992 and 2011, mostly between 2006 and 2011 (70.7%) and conducted in North America (62.7%). Most samples consisted of adolescents of both sexes (76%) and 48% involved an age range between 10 and 19 years. Studies with a cross-sectional design were the most common (85.3%) as well as those with non-probabilistic samples (58.7%) and composed of 100–1000 adolescents (66.7%). Information on these studies is presented in Table II.

Characteristics of the studies that analyzed the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents aged 10–19 years

| Variables . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Publication year | |

| 1992–99 | 6 (8.0) |

| 2001–05 | 16 (21.3) |

| 2006–11 | 53 (70.7) |

| Origin of sample | |

| North America | 47 (62.7) |

| Europe | 13 (17.3) |

| Oceania | 7 (9.3) |

| Asia | 5 (6.7) |

| South America | 2 (2.7) |

| Oceania and Asiaa | 1 (1.3) |

| Frequency by countriesb | |

| USA | 42 (89.4) |

| Norway | 3 (23.1) |

| Australia | 6 (85.7) |

| China | 2 (40.0) |

| Brazil | 2 (100.0) |

| China and Australia | 1 (100.0) |

| Others | 19 (100.0) |

| Sex sample | |

| Male | 1 (1.3) |

| Female | 17 (22.7) |

| Male and Female | 57 (76.0) |

| Age groupc (years) | |

| 10–14 | 28 (37.3) |

| 15–19 | 2 (2.7) |

| 10–19 | 36 (48.0) |

| Sample size (no. of subjects) | |

| <100 | 7 (9.3) |

| 100–1000 | 50 (66.7) |

| 1001–5000 | 15 (20.0) |

| >5000 | 3 (4.0) |

| Sample type | |

| Probabilistic | 31 (41.3) |

| Non-probabilistic | 44 (58.7) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 64 (85.3) |

| Intervention | 2 (2.7) |

| Longitudinal | 9 (12.0) |

| Variables . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Publication year | |

| 1992–99 | 6 (8.0) |

| 2001–05 | 16 (21.3) |

| 2006–11 | 53 (70.7) |

| Origin of sample | |

| North America | 47 (62.7) |

| Europe | 13 (17.3) |

| Oceania | 7 (9.3) |

| Asia | 5 (6.7) |

| South America | 2 (2.7) |

| Oceania and Asiaa | 1 (1.3) |

| Frequency by countriesb | |

| USA | 42 (89.4) |

| Norway | 3 (23.1) |

| Australia | 6 (85.7) |

| China | 2 (40.0) |

| Brazil | 2 (100.0) |

| China and Australia | 1 (100.0) |

| Others | 19 (100.0) |

| Sex sample | |

| Male | 1 (1.3) |

| Female | 17 (22.7) |

| Male and Female | 57 (76.0) |

| Age groupc (years) | |

| 10–14 | 28 (37.3) |

| 15–19 | 2 (2.7) |

| 10–19 | 36 (48.0) |

| Sample size (no. of subjects) | |

| <100 | 7 (9.3) |

| 100–1000 | 50 (66.7) |

| 1001–5000 | 15 (20.0) |

| >5000 | 3 (4.0) |

| Sample type | |

| Probabilistic | 31 (41.3) |

| Non-probabilistic | 44 (58.7) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 64 (85.3) |

| Intervention | 2 (2.7) |

| Longitudinal | 9 (12.0) |

aStudy performed with samples from two continents. bValues proportional to the sample origin Others (all the other countries). cNine articles reported only average age.

Characteristics of the studies that analyzed the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents aged 10–19 years

| Variables . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Publication year | |

| 1992–99 | 6 (8.0) |

| 2001–05 | 16 (21.3) |

| 2006–11 | 53 (70.7) |

| Origin of sample | |

| North America | 47 (62.7) |

| Europe | 13 (17.3) |

| Oceania | 7 (9.3) |

| Asia | 5 (6.7) |

| South America | 2 (2.7) |

| Oceania and Asiaa | 1 (1.3) |

| Frequency by countriesb | |

| USA | 42 (89.4) |

| Norway | 3 (23.1) |

| Australia | 6 (85.7) |

| China | 2 (40.0) |

| Brazil | 2 (100.0) |

| China and Australia | 1 (100.0) |

| Others | 19 (100.0) |

| Sex sample | |

| Male | 1 (1.3) |

| Female | 17 (22.7) |

| Male and Female | 57 (76.0) |

| Age groupc (years) | |

| 10–14 | 28 (37.3) |

| 15–19 | 2 (2.7) |

| 10–19 | 36 (48.0) |

| Sample size (no. of subjects) | |

| <100 | 7 (9.3) |

| 100–1000 | 50 (66.7) |

| 1001–5000 | 15 (20.0) |

| >5000 | 3 (4.0) |

| Sample type | |

| Probabilistic | 31 (41.3) |

| Non-probabilistic | 44 (58.7) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 64 (85.3) |

| Intervention | 2 (2.7) |

| Longitudinal | 9 (12.0) |

| Variables . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Publication year | |

| 1992–99 | 6 (8.0) |

| 2001–05 | 16 (21.3) |

| 2006–11 | 53 (70.7) |

| Origin of sample | |

| North America | 47 (62.7) |

| Europe | 13 (17.3) |

| Oceania | 7 (9.3) |

| Asia | 5 (6.7) |

| South America | 2 (2.7) |

| Oceania and Asiaa | 1 (1.3) |

| Frequency by countriesb | |

| USA | 42 (89.4) |

| Norway | 3 (23.1) |

| Australia | 6 (85.7) |

| China | 2 (40.0) |

| Brazil | 2 (100.0) |

| China and Australia | 1 (100.0) |

| Others | 19 (100.0) |

| Sex sample | |

| Male | 1 (1.3) |

| Female | 17 (22.7) |

| Male and Female | 57 (76.0) |

| Age groupc (years) | |

| 10–14 | 28 (37.3) |

| 15–19 | 2 (2.7) |

| 10–19 | 36 (48.0) |

| Sample size (no. of subjects) | |

| <100 | 7 (9.3) |

| 100–1000 | 50 (66.7) |

| 1001–5000 | 15 (20.0) |

| >5000 | 3 (4.0) |

| Sample type | |

| Probabilistic | 31 (41.3) |

| Non-probabilistic | 44 (58.7) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 64 (85.3) |

| Intervention | 2 (2.7) |

| Longitudinal | 9 (12.0) |

aStudy performed with samples from two continents. bValues proportional to the sample origin Others (all the other countries). cNine articles reported only average age.

Measures of physical activity and social support

In most of the studies, physical activity was measured using a subjective method (77.3%), particularly the use of questionnaires (64%). Accelerometers and pedometers accounted for 17.3% of all measures of physical activity and only 5.3% of the studies combined objective and subjective measures. In 68% of the studies, the physical activity domains measured were not defined, 20% measured leisure-time physical activity and 12% combined leisure and commuting. Only four studies did not report the psychometric properties of the instruments (reliability and validity) or inform whether they had been previously tested.

A total of 11 different sources of social support for physical activity were identified (general social support, parents, father, mother, friends, family, siblings, teachers, other adults, school environment and coaches). In 74.7% of the studies, up to two sources of social support were measured, highlighting the social support provided by friends, evaluated in 64% of the studies. This was followed by social support from family (36%) and parents (35%). The sources of social support from other adults, the school environment and coaches were evaluated in only one study each, and were excluded from analysis. Seven studies did not report on psychometric properties (internal consistency, reliability and validity) or whether the instruments had been previously tested.

The most widely used statistical analyses to check the association between physical activity and social support were regression models (72%), followed by structural equation modeling (18.7%), analysis of variance or covariance (6.7%) and correlation (2.6%). Details about the measures of physical activity and social support are described in Table III.

Characteristics of the measures of physical activity and social support, and assessment quality of studies

| Author . | Year . | Countrya . | PA domain . | Type of instrument . | Tested the PA instrument . | Tested the SS instrument . | No. of SS sources . | Statistical analysis . | Quality of study . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point . | Level . | |||||||||

| Anderssen and Wold [26] | 1992 | NOR | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Zakarian et al. [27] | 1994 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Biddle and Goudas [28] | 1996 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 2 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Bungum and Vincent [29] | 1997 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Vilhjalmsson and Thorlindsson [30] | 1998 | ISL | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 5 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Sallis et al. [31] | 1999 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modelimg | 66.7 | B |

| Strauss et al. [32] | 2001 | USA | Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Prochaska et al. [33] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Rhodes et al. [34] | 2002 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 29.2 | C |

| Sallis et al. [13] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wu and Pender [35] | 2002 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Higgins et al. [36] | 2003 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. [37] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Trost et al. [38] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Wu et al. [39] | 2003 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Davison [14] | 2004 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 5 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Saunders et al. [40] | 2004 | USA | Overall and leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Bourdeaudhuij et al. [41] | 2005 | BEL | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Duncan [4] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and pedometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Frenn et al. [42] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Reis and Petroski [43] | 2005 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 33.3 | C |

| Voorhees et al. [16] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Beets et al. [5] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Davison et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Correlation | 41.7 | C |

| Davison and Schmalz [45] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Heitzler et al. [46] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Ommundsen et al. [47] | 2006 | NOR | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Raudsepp [48] | 2006 | EST | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Springer et al. [49] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Zhang and DeBate [50] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Beets et al. [51] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Beets et al. [52] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Dowda et al. [53] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Hohepa et al. [54] | 2007 | NZL | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Kuo et al. [55] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Lubans et al. [56] | 2007 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Motl et al. [57] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 45.8 | C |

| Wilson and Dollman [58] | 2007 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Hamilton and White [59] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Jackson et al. [60] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| King et al. [61] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Lown and Braunschweig [62] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Martin and McCaughtry [63] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 37.5 | C |

| Martin and McCaughtry [64] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Martin et al. [65] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| McMinn et al. [66] | 2008 | DNK | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Robbins et al. [67] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 6 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Sabiston and Crocker [68] | 2008 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Shields et al. [69] | 2008 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Davison and Jago [70] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Dishman [71] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 62.5 | B |

| Há et al. [72] | 2009 | AUS/CHN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Variance/Covariance | 45.8 | C |

| Kurc and Leatherdale [73] | 2009 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Loucaides [74] | 2009 | CYP | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Correlation | 66.7 | B |

| Lubans and Morgan [75] | 2009 | AUS | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Maglione and Hayman [76] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Panter et al. [18] | 2009 | GBR | Commuting | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wenthe et al. [77] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Wilson and Dollman [17] | 2009 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 33.3 | C |

| Barr-Anderson et al. [7] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Deforche et al. [78] | 2010 | BEL | Leisure and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Dishman et al. [79] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Fermino et al. [80] | 2010 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 91.7 | A |

| Kelly et al. [81] | 2010 | USA | Overall and Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Kim and Cardinal [82] | 2010 | KOR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al. [83] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Lee et al. [84] | 2010 | SGP | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Leslie et al. [85] | 2010 | AUS | Commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Patnode et al. [86] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Taymoori et al. [87] | 2010 | IRN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Bergh et al. [88] | 2011 | NOR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Bradley et al. [89] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Hsu et al. [90] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 70.8 | A |

| Jago et al. [91] | 2011 | GBR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Martin et al. [92] | 2011 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Author . | Year . | Countrya . | PA domain . | Type of instrument . | Tested the PA instrument . | Tested the SS instrument . | No. of SS sources . | Statistical analysis . | Quality of study . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point . | Level . | |||||||||

| Anderssen and Wold [26] | 1992 | NOR | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Zakarian et al. [27] | 1994 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Biddle and Goudas [28] | 1996 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 2 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Bungum and Vincent [29] | 1997 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Vilhjalmsson and Thorlindsson [30] | 1998 | ISL | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 5 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Sallis et al. [31] | 1999 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modelimg | 66.7 | B |

| Strauss et al. [32] | 2001 | USA | Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Prochaska et al. [33] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Rhodes et al. [34] | 2002 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 29.2 | C |

| Sallis et al. [13] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wu and Pender [35] | 2002 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Higgins et al. [36] | 2003 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. [37] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Trost et al. [38] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Wu et al. [39] | 2003 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Davison [14] | 2004 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 5 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Saunders et al. [40] | 2004 | USA | Overall and leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Bourdeaudhuij et al. [41] | 2005 | BEL | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Duncan [4] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and pedometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Frenn et al. [42] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Reis and Petroski [43] | 2005 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 33.3 | C |

| Voorhees et al. [16] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Beets et al. [5] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Davison et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Correlation | 41.7 | C |

| Davison and Schmalz [45] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Heitzler et al. [46] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Ommundsen et al. [47] | 2006 | NOR | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Raudsepp [48] | 2006 | EST | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Springer et al. [49] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Zhang and DeBate [50] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Beets et al. [51] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Beets et al. [52] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Dowda et al. [53] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Hohepa et al. [54] | 2007 | NZL | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Kuo et al. [55] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Lubans et al. [56] | 2007 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Motl et al. [57] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 45.8 | C |

| Wilson and Dollman [58] | 2007 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Hamilton and White [59] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Jackson et al. [60] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| King et al. [61] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Lown and Braunschweig [62] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Martin and McCaughtry [63] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 37.5 | C |

| Martin and McCaughtry [64] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Martin et al. [65] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| McMinn et al. [66] | 2008 | DNK | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Robbins et al. [67] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 6 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Sabiston and Crocker [68] | 2008 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Shields et al. [69] | 2008 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Davison and Jago [70] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Dishman [71] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 62.5 | B |

| Há et al. [72] | 2009 | AUS/CHN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Variance/Covariance | 45.8 | C |

| Kurc and Leatherdale [73] | 2009 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Loucaides [74] | 2009 | CYP | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Correlation | 66.7 | B |

| Lubans and Morgan [75] | 2009 | AUS | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Maglione and Hayman [76] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Panter et al. [18] | 2009 | GBR | Commuting | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wenthe et al. [77] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Wilson and Dollman [17] | 2009 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 33.3 | C |

| Barr-Anderson et al. [7] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Deforche et al. [78] | 2010 | BEL | Leisure and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Dishman et al. [79] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Fermino et al. [80] | 2010 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 91.7 | A |

| Kelly et al. [81] | 2010 | USA | Overall and Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Kim and Cardinal [82] | 2010 | KOR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al. [83] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Lee et al. [84] | 2010 | SGP | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Leslie et al. [85] | 2010 | AUS | Commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Patnode et al. [86] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Taymoori et al. [87] | 2010 | IRN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Bergh et al. [88] | 2011 | NOR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Bradley et al. [89] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Hsu et al. [90] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 70.8 | A |

| Jago et al. [91] | 2011 | GBR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Martin et al. [92] | 2011 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

aAbbreviations according to the Brazilian Association of International Transport Companies (ABRETI) [93]; NI, not informed; PA, physical activity; SS, social support.

Characteristics of the measures of physical activity and social support, and assessment quality of studies

| Author . | Year . | Countrya . | PA domain . | Type of instrument . | Tested the PA instrument . | Tested the SS instrument . | No. of SS sources . | Statistical analysis . | Quality of study . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point . | Level . | |||||||||

| Anderssen and Wold [26] | 1992 | NOR | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Zakarian et al. [27] | 1994 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Biddle and Goudas [28] | 1996 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 2 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Bungum and Vincent [29] | 1997 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Vilhjalmsson and Thorlindsson [30] | 1998 | ISL | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 5 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Sallis et al. [31] | 1999 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modelimg | 66.7 | B |

| Strauss et al. [32] | 2001 | USA | Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Prochaska et al. [33] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Rhodes et al. [34] | 2002 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 29.2 | C |

| Sallis et al. [13] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wu and Pender [35] | 2002 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Higgins et al. [36] | 2003 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. [37] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Trost et al. [38] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Wu et al. [39] | 2003 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Davison [14] | 2004 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 5 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Saunders et al. [40] | 2004 | USA | Overall and leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Bourdeaudhuij et al. [41] | 2005 | BEL | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Duncan [4] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and pedometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Frenn et al. [42] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Reis and Petroski [43] | 2005 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 33.3 | C |

| Voorhees et al. [16] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Beets et al. [5] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Davison et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Correlation | 41.7 | C |

| Davison and Schmalz [45] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Heitzler et al. [46] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Ommundsen et al. [47] | 2006 | NOR | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Raudsepp [48] | 2006 | EST | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Springer et al. [49] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Zhang and DeBate [50] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Beets et al. [51] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Beets et al. [52] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Dowda et al. [53] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Hohepa et al. [54] | 2007 | NZL | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Kuo et al. [55] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Lubans et al. [56] | 2007 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Motl et al. [57] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 45.8 | C |

| Wilson and Dollman [58] | 2007 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Hamilton and White [59] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Jackson et al. [60] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| King et al. [61] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Lown and Braunschweig [62] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Martin and McCaughtry [63] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 37.5 | C |

| Martin and McCaughtry [64] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Martin et al. [65] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| McMinn et al. [66] | 2008 | DNK | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Robbins et al. [67] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 6 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Sabiston and Crocker [68] | 2008 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Shields et al. [69] | 2008 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Davison and Jago [70] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Dishman [71] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 62.5 | B |

| Há et al. [72] | 2009 | AUS/CHN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Variance/Covariance | 45.8 | C |

| Kurc and Leatherdale [73] | 2009 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Loucaides [74] | 2009 | CYP | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Correlation | 66.7 | B |

| Lubans and Morgan [75] | 2009 | AUS | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Maglione and Hayman [76] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Panter et al. [18] | 2009 | GBR | Commuting | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wenthe et al. [77] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Wilson and Dollman [17] | 2009 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 33.3 | C |

| Barr-Anderson et al. [7] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Deforche et al. [78] | 2010 | BEL | Leisure and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Dishman et al. [79] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Fermino et al. [80] | 2010 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 91.7 | A |

| Kelly et al. [81] | 2010 | USA | Overall and Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Kim and Cardinal [82] | 2010 | KOR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al. [83] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Lee et al. [84] | 2010 | SGP | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Leslie et al. [85] | 2010 | AUS | Commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Patnode et al. [86] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Taymoori et al. [87] | 2010 | IRN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Bergh et al. [88] | 2011 | NOR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Bradley et al. [89] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Hsu et al. [90] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 70.8 | A |

| Jago et al. [91] | 2011 | GBR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Martin et al. [92] | 2011 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Author . | Year . | Countrya . | PA domain . | Type of instrument . | Tested the PA instrument . | Tested the SS instrument . | No. of SS sources . | Statistical analysis . | Quality of study . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point . | Level . | |||||||||

| Anderssen and Wold [26] | 1992 | NOR | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Zakarian et al. [27] | 1994 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Biddle and Goudas [28] | 1996 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 2 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Bungum and Vincent [29] | 1997 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Vilhjalmsson and Thorlindsson [30] | 1998 | ISL | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 5 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Sallis et al. [31] | 1999 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modelimg | 66.7 | B |

| Strauss et al. [32] | 2001 | USA | Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Prochaska et al. [33] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Rhodes et al. [34] | 2002 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 29.2 | C |

| Sallis et al. [13] | 2002 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wu and Pender [35] | 2002 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Higgins et al. [36] | 2003 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. [37] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Trost et al. [38] | 2003 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Wu et al. [39] | 2003 | CHN | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Davison [14] | 2004 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 5 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Saunders et al. [40] | 2004 | USA | Overall and leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Bourdeaudhuij et al. [41] | 2005 | BEL | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Duncan [4] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and pedometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Frenn et al. [42] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Reis and Petroski [43] | 2005 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 33.3 | C |

| Voorhees et al. [16] | 2005 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Beets et al. [5] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 50.0 | C |

| Davison et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Correlation | 41.7 | C |

| Davison and Schmalz [45] | 2006 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Heitzler et al. [46] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Ommundsen et al. [47] | 2006 | NOR | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Raudsepp [48] | 2006 | EST | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Springer et al. [49] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Zhang and DeBate [50] | 2006 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Beets et al. [51] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Beets et al. [52] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Structural equation | 66.7 | B |

| Dowda et al. [53] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Hohepa et al. [54] | 2007 | NZL | Leisure, school and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Kuo et al. [55] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Lubans et al. [56] | 2007 | GBR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Motl et al. [57] | 2007 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 45.8 | C |

| Wilson and Dollman [58] | 2007 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Hamilton and White [59] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Jackson et al. [60] | 2008 | AUS | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| King et al. [61] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Variance/Covariance | 50.0 | C |

| Lown and Braunschweig [62] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Martin and McCaughtry [63] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 37.5 | C |

| Martin and McCaughtry [64] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 50.0 | C |

| Martin et al. [65] | 2008 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| McMinn et al. [66] | 2008 | DNK | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Robbins et al. [67] | 2008 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 6 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Sabiston and Crocker [68] | 2008 | CAN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 54.2 | B |

| Shields et al. [69] | 2008 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Davison and Jago [70] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Dishman [71] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Structural equation | 62.5 | B |

| Há et al. [72] | 2009 | AUS/CHN | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 4 | Variance/Covariance | 45.8 | C |

| Kurc and Leatherdale [73] | 2009 | CAN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Loucaides [74] | 2009 | CYP | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Correlation | 66.7 | B |

| Lubans and Morgan [75] | 2009 | AUS | Overall | Pedometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 62.5 | B |

| Maglione and Hayman [76] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Panter et al. [18] | 2009 | GBR | Commuting | Questionnaire | NI | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Wenthe et al. [77] | 2009 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire and accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Wilson and Dollman [17] | 2009 | AUS | Overall and Leisure | Recall | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 33.3 | C |

| Barr-Anderson et al. [7] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

| Deforche et al. [78] | 2010 | BEL | Leisure and commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 66.7 | B |

| Dishman et al. [79] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 58.3 | B |

| Fermino et al. [80] | 2010 | BRA | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 91.7 | A |

| Kelly et al. [81] | 2010 | USA | Overall and Leisure | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Kim and Cardinal [82] | 2010 | KOR | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 75.0 | A |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al. [83] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Lee et al. [84] | 2010 | SGP | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Leslie et al. [85] | 2010 | AUS | Commuting | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 58.3 | B |

| Patnode et al. [86] | 2010 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 75.0 | A |

| Taymoori et al. [87] | 2010 | IRN | Overall | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 4 | Regression modeling | 79.2 | A |

| Bergh et al. [88] | 2011 | NOR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 3 | Regression modeling | 83.3 | A |

| Bradley et al. [89] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | NI | 1 | Regression modeling | 70.8 | A |

| Hsu et al. [90] | 2011 | USA | Overall | Recall | Yes | Yes | 2 | Structural equation | 70.8 | A |

| Jago et al. [91] | 2011 | GBR | Overall | Accelerometer | Yes | Yes | 2 | Regression modeling | 45.8 | C |

| Martin et al. [92] | 2011 | USA | Leisure | Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | 1 | Regression modeling | 54.2 | B |

aAbbreviations according to the Brazilian Association of International Transport Companies (ABRETI) [93]; NI, not informed; PA, physical activity; SS, social support.

Evaluating study quality

In relation to study quality (Table III), 45.3% were classified as level B, followed by levels A (34.7%) and C (20%). The items referring to sample power (0.2 mean value) and representativeness (0.7 mean value) had the lowest mean values. Appropriate statistical tests and adequate description of the results were the items that obtained the highest average in assessment of study quality (1.8 and 1.7 mean values, respectively).

Evidence of the association between physical activity and social support

In general, social support was positive and consistently associated with the overall physical activity levels of adolescents (overall physical activity = sum of all physical activities investigated). The measure of general social support, and that of parents, father, friends and family showed consistent evidence of a positive association (‘++’) with overall physical activity levels (Table IV). The same behavior was observed when studies were stratified by methodological method (data not reported in the tables).

Synthesis of studies that evaluate the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents

| . | Related to physical activity . | Not related to physical activity . | Synthesis . | Evidence . | Percent of evidence for study qualitya . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of SS . | Positive association (‘+’) . | Negative association (‘−’) . | No. association (‘0’) . | No. S . | No. IS . | + . | − . | 0 . | n/N . | % . | Cod . | A(≥70) . | B(69–51) . | C(≤50) . |

| Overall | [32]; [37]F; [42]F; [50]; [57]F; [71]F | [76]; [36]; [42]M | 8 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6/9 | 66.7 | ++ | 16.7 | 66.6 | 16.7 | |

| Parents | [4]; [28]; [26]M/F; [38]; [44]F; [46]; [47]; [54]; [56]M/F; [61]; [70]F; [73]F/M; [74]; [18]; [84]M/F; [89]M/F | [60]M | [68]; [33]; [39]M/F; [60]F; [63]; [64]; [65]; [66]; [86]M/F; [88] | 26 | 34 | 21 | 1 | 12 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 43.8 | 37.5 | 18.8 |

| Father | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M/F; [45]; [48]; [51]M; [58]M; [67]; [72]; [17]F; [91]M | [30]; [51]F; [52]F; [87]F; [91]F | 14 | 18 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 13/18 | 72.2 | ++ | 23.1 | 30.8 | 46.2 | |

| Mother | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M; [45]; [51]F; [58]M; [72]; [17]F | [30]; [14]F; [51]M; [48]; [52]F; [30]; [87]F; [91]M/F | 14 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9/18 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Friends | [4]; [5]; [68]; [26]M/F; [27]M/F; [30]; [34]; [13]M; [35]; [39]M/F; [14]M/F; [41]; [16]F; [45]; [47]; [49]F; [52]F; [54]; [56]M/F; [58]M; [72]; [62]F; [64]; [67]; [70]F; [72]; [74]; [75]F; [18]; [78]; [80]; [81]F; [82]; [85]M; [86]M; [88]; [92] | [59]; [29]F; [33]; [13]F; [43]M/F; [65]; [66]; [75]M; [77]M/F; [17]F; [79]F; [85]F; [86]F; [87]F; [90] | 48 | 59 | 42 | 0 | 17 | 42/59 | 71.2 | ++ | 35.1 | 48.6 | 16.2 | |

| Family | [7]; [27]M/F; [31]; [34]; [14]F; [40]F; [41]; [43]M; [49]F; [53]F; [55]F; [62]F; [69]; [77]M/F; [78]; [80]; [82]; [83]M; [90] | [35]; [85]F | [59]; [29]F; [13]M/F; [14]M; [43]F; [67]; [79]F; [81]F; [83]F; [85]M | 27 | 34 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 36.8 | 42.1 | 21.1 |

| Siblings | [4]; [14]M/F; [45]; [54] | [30]; [64]; [65]; [67]; [87]F; | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5/10 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Teacher | [28]; [72]; [17]F | [27]M/F; [41]; [47]; [58]M; [67]; [88] | 9 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 7/10 | 70.0 | 00 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 | |

| . | Related to physical activity . | Not related to physical activity . | Synthesis . | Evidence . | Percent of evidence for study qualitya . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of SS . | Positive association (‘+’) . | Negative association (‘−’) . | No. association (‘0’) . | No. S . | No. IS . | + . | − . | 0 . | n/N . | % . | Cod . | A(≥70) . | B(69–51) . | C(≤50) . |

| Overall | [32]; [37]F; [42]F; [50]; [57]F; [71]F | [76]; [36]; [42]M | 8 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6/9 | 66.7 | ++ | 16.7 | 66.6 | 16.7 | |

| Parents | [4]; [28]; [26]M/F; [38]; [44]F; [46]; [47]; [54]; [56]M/F; [61]; [70]F; [73]F/M; [74]; [18]; [84]M/F; [89]M/F | [60]M | [68]; [33]; [39]M/F; [60]F; [63]; [64]; [65]; [66]; [86]M/F; [88] | 26 | 34 | 21 | 1 | 12 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 43.8 | 37.5 | 18.8 |

| Father | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M/F; [45]; [48]; [51]M; [58]M; [67]; [72]; [17]F; [91]M | [30]; [51]F; [52]F; [87]F; [91]F | 14 | 18 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 13/18 | 72.2 | ++ | 23.1 | 30.8 | 46.2 | |

| Mother | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M; [45]; [51]F; [58]M; [72]; [17]F | [30]; [14]F; [51]M; [48]; [52]F; [30]; [87]F; [91]M/F | 14 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9/18 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Friends | [4]; [5]; [68]; [26]M/F; [27]M/F; [30]; [34]; [13]M; [35]; [39]M/F; [14]M/F; [41]; [16]F; [45]; [47]; [49]F; [52]F; [54]; [56]M/F; [58]M; [72]; [62]F; [64]; [67]; [70]F; [72]; [74]; [75]F; [18]; [78]; [80]; [81]F; [82]; [85]M; [86]M; [88]; [92] | [59]; [29]F; [33]; [13]F; [43]M/F; [65]; [66]; [75]M; [77]M/F; [17]F; [79]F; [85]F; [86]F; [87]F; [90] | 48 | 59 | 42 | 0 | 17 | 42/59 | 71.2 | ++ | 35.1 | 48.6 | 16.2 | |

| Family | [7]; [27]M/F; [31]; [34]; [14]F; [40]F; [41]; [43]M; [49]F; [53]F; [55]F; [62]F; [69]; [77]M/F; [78]; [80]; [82]; [83]M; [90] | [35]; [85]F | [59]; [29]F; [13]M/F; [14]M; [43]F; [67]; [79]F; [81]F; [83]F; [85]M | 27 | 34 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 36.8 | 42.1 | 21.1 |

| Siblings | [4]; [14]M/F; [45]; [54] | [30]; [64]; [65]; [67]; [87]F; | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5/10 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Teacher | [28]; [72]; [17]F | [27]M/F; [41]; [47]; [58]M; [67]; [88] | 9 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 7/10 | 70.0 | 00 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 | |

Reference citations in brackets; SS, social support; No.S, number of studies; No. IS, number of independent samples; n/N = proportion of independent samples by source of social support; Cod, code summary of association; M, male; F, female; aDistribution of the level of quality of the studies was shown as ++ and 00.

Synthesis of studies that evaluate the association between physical activity and social support in adolescents

| . | Related to physical activity . | Not related to physical activity . | Synthesis . | Evidence . | Percent of evidence for study qualitya . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of SS . | Positive association (‘+’) . | Negative association (‘−’) . | No. association (‘0’) . | No. S . | No. IS . | + . | − . | 0 . | n/N . | % . | Cod . | A(≥70) . | B(69–51) . | C(≤50) . |

| Overall | [32]; [37]F; [42]F; [50]; [57]F; [71]F | [76]; [36]; [42]M | 8 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6/9 | 66.7 | ++ | 16.7 | 66.6 | 16.7 | |

| Parents | [4]; [28]; [26]M/F; [38]; [44]F; [46]; [47]; [54]; [56]M/F; [61]; [70]F; [73]F/M; [74]; [18]; [84]M/F; [89]M/F | [60]M | [68]; [33]; [39]M/F; [60]F; [63]; [64]; [65]; [66]; [86]M/F; [88] | 26 | 34 | 21 | 1 | 12 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 43.8 | 37.5 | 18.8 |

| Father | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M/F; [45]; [48]; [51]M; [58]M; [67]; [72]; [17]F; [91]M | [30]; [51]F; [52]F; [87]F; [91]F | 14 | 18 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 13/18 | 72.2 | ++ | 23.1 | 30.8 | 46.2 | |

| Mother | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M; [45]; [51]F; [58]M; [72]; [17]F | [30]; [14]F; [51]M; [48]; [52]F; [30]; [87]F; [91]M/F | 14 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9/18 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Friends | [4]; [5]; [68]; [26]M/F; [27]M/F; [30]; [34]; [13]M; [35]; [39]M/F; [14]M/F; [41]; [16]F; [45]; [47]; [49]F; [52]F; [54]; [56]M/F; [58]M; [72]; [62]F; [64]; [67]; [70]F; [72]; [74]; [75]F; [18]; [78]; [80]; [81]F; [82]; [85]M; [86]M; [88]; [92] | [59]; [29]F; [33]; [13]F; [43]M/F; [65]; [66]; [75]M; [77]M/F; [17]F; [79]F; [85]F; [86]F; [87]F; [90] | 48 | 59 | 42 | 0 | 17 | 42/59 | 71.2 | ++ | 35.1 | 48.6 | 16.2 | |

| Family | [7]; [27]M/F; [31]; [34]; [14]F; [40]F; [41]; [43]M; [49]F; [53]F; [55]F; [62]F; [69]; [77]M/F; [78]; [80]; [82]; [83]M; [90] | [35]; [85]F | [59]; [29]F; [13]M/F; [14]M; [43]F; [67]; [79]F; [81]F; [83]F; [85]M | 27 | 34 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 36.8 | 42.1 | 21.1 |

| Siblings | [4]; [14]M/F; [45]; [54] | [30]; [64]; [65]; [67]; [87]F; | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5/10 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Teacher | [28]; [72]; [17]F | [27]M/F; [41]; [47]; [58]M; [67]; [88] | 9 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 7/10 | 70.0 | 00 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 | |

| . | Related to physical activity . | Not related to physical activity . | Synthesis . | Evidence . | Percent of evidence for study qualitya . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of SS . | Positive association (‘+’) . | Negative association (‘−’) . | No. association (‘0’) . | No. S . | No. IS . | + . | − . | 0 . | n/N . | % . | Cod . | A(≥70) . | B(69–51) . | C(≤50) . |

| Overall | [32]; [37]F; [42]F; [50]; [57]F; [71]F | [76]; [36]; [42]M | 8 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6/9 | 66.7 | ++ | 16.7 | 66.6 | 16.7 | |

| Parents | [4]; [28]; [26]M/F; [38]; [44]F; [46]; [47]; [54]; [56]M/F; [61]; [70]F; [73]F/M; [74]; [18]; [84]M/F; [89]M/F | [60]M | [68]; [33]; [39]M/F; [60]F; [63]; [64]; [65]; [66]; [86]M/F; [88] | 26 | 34 | 21 | 1 | 12 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 43.8 | 37.5 | 18.8 |

| Father | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M/F; [45]; [48]; [51]M; [58]M; [67]; [72]; [17]F; [91]M | [30]; [51]F; [52]F; [87]F; [91]F | 14 | 18 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 13/18 | 72.2 | ++ | 23.1 | 30.8 | 46.2 | |

| Mother | [5]; [26]M/F; [14]M; [45]; [51]F; [58]M; [72]; [17]F | [30]; [14]F; [51]M; [48]; [52]F; [30]; [87]F; [91]M/F | 14 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9/18 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Friends | [4]; [5]; [68]; [26]M/F; [27]M/F; [30]; [34]; [13]M; [35]; [39]M/F; [14]M/F; [41]; [16]F; [45]; [47]; [49]F; [52]F; [54]; [56]M/F; [58]M; [72]; [62]F; [64]; [67]; [70]F; [72]; [74]; [75]F; [18]; [78]; [80]; [81]F; [82]; [85]M; [86]M; [88]; [92] | [59]; [29]F; [33]; [13]F; [43]M/F; [65]; [66]; [75]M; [77]M/F; [17]F; [79]F; [85]F; [86]F; [87]F; [90] | 48 | 59 | 42 | 0 | 17 | 42/59 | 71.2 | ++ | 35.1 | 48.6 | 16.2 | |

| Family | [7]; [27]M/F; [31]; [34]; [14]F; [40]F; [41]; [43]M; [49]F; [53]F; [55]F; [62]F; [69]; [77]M/F; [78]; [80]; [82]; [83]M; [90] | [35]; [85]F | [59]; [29]F; [13]M/F; [14]M; [43]F; [67]; [79]F; [81]F; [83]F; [85]M | 27 | 34 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 21/34 | 61.8 | ++ | 36.8 | 42.1 | 21.1 |

| Siblings | [4]; [14]M/F; [45]; [54] | [30]; [64]; [65]; [67]; [87]F; | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5/10 | 50.0 | ?? | − | − | − | |

| Teacher | [28]; [72]; [17]F | [27]M/F; [41]; [47]; [58]M; [67]; [88] | 9 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 7/10 | 70.0 | 00 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 | |

Reference citations in brackets; SS, social support; No.S, number of studies; No. IS, number of independent samples; n/N = proportion of independent samples by source of social support; Cod, code summary of association; M, male; F, female; aDistribution of the level of quality of the studies was shown as ++ and 00.

The results showed that there is no association (‘00’) between physical activity and social support from teachers. The evidence for an association between social support from the mother and siblings and higher overall physical activity was inconsistent, with no clear definition of the direction of the measures of association found (‘??’). In both cases, 50% of the results showed a positive association and 50% showed no significant association between physical activity and social support.

When analyses were stratified by physical activity domain and intensity, the results of independent samples showed variations for associations between social support and physical activity. For leisure-time physical activities, social support of parents, father, mother and friends was positively and consistently (++) associated with physical activity. For commuting physical activities, only social support from friends was positively and consistently (++) associated with higher levels. In analysis of physical activity intensity, fathers, mothers and friends were positive sources of social support consistently (++) associated to vigorous physical activity (data not reported in tables).

Eleven studies analyzed the association between different types of social support and physical activity in adolescents. Of these, 10 [5, 7, 14, 17, 49, 51, 60, 67, 82, 89] found a significant association between some type of social support from the instrumental/direct dimension (e.g. participation in activities with other people, transportation and invitation to participate) and eight [4, 5, 17, 49, 60, 67, 82, 89] with some type of psychological/emotional dimension (e.g. encouragement, watching, praise) and the level of physical activity in adolescents. No significant association was found between types of support related to the instructional/informative dimension (e.g. comments on the benefits of exercise and how to correctly perform them) and physical activity in adolescents (data not reported in tables).

When social support was provided by the parents, the most frequent types of support associated to physical activity in adolescents were: encouragement (6 of 11 articles) [5, 17, 49, 67, 82, 89], do activity with (4 of 11) [7, 17, 51, 60] and transportation (3 of 11) [7, 67, 89]. When social support was provided by friends, encouragement (3 of 11 articles) [5, 26, 30] and do activity with (2 of 11) [49, 82] were the types most frequently associated with physical activity in adolescents. Watching [4], praising [60] and helping [17] were also positively associated to physical activity in adolescents (data not reported in tables).

Of the nine studies [34, 44, 59, 69, 70–72, 89] with longitudinal design that assessed the relationship between the social support provided by family members (parents, father and mother) and friends and physical activity in adolescents, eight [34, 44, 69, 70–72, 89] observed that increasing and/or maintaining social support on the part of these sources is associated with increasing and/or maintaining physical activity in adolescents (data not reported in tables). However, due to the low number of studies (fewer than three independent samples for each source of social support), it was impossible to determine if the longitudinal associations between social support and physical activity varied according to the sex and age of the adolescent, or with the domain or intensity of physical activity (data not reported in tables).

Discussion

The main findings of this systematic review showed a consistent and positive association between the provision of overall social support by parents, father, friends and family and more involvement of adolescents in overall physical activity. Encouragement and do activity with were the most frequent types of social support associated to physical activity in adolescents. With respect to leisure physical activities, associations were positive and consistent for social support provided by parents, father, mother and friends.

The use of a reference guide to conduct this systematic review, the searches in different electronic databases, clear definition of ratings used to summarize the study results, independent assessments by two reviewers at all stages of the study (search for and selection of articles, quality assessment and data extraction) and evaluation of article quality contributed to the quality of this review.

Over 90% of the studies analyzed were published in the last decade, predominantly in the last 6 years (2006–11). The increasing number of investigations of the factors associated with physical activity in adolescents, including social support, can be explained by the need and importance that has been given to identifying and understanding the mechanisms by which these factors influence their participation in this type of activity [1, 8–11].

The use of non-probabilistic samples in 58.7% of studies and the fact that most were concentrated in North America and Europe, may limit generalizability of the results. Due to economic, environmental and sociocultural differences between countries with different levels of development, the results can not be directly applied to low and middle income countries. Moreover, the use of non-probabilistic samples makes the study more susceptible to selection bias, increasing the likelihood of producing estimates that do not really correspond to associations existing in the population of reference [94].

Quality assessment showed that 80% of the studies selected for this review were classified as medium to high quality. Nevertheless, indicators such as sample representativeness and statistical power exhibited very low average values, indicating the absence of these items in 52 and 84% of the studies, respectively. These factors may contribute to greater susceptibility to selection bias and the possibility of type II error.

In general, it was consistently observed that adolescents who received more social support had higher levels of overall physical activity, particularly when this support was provided by parents, father, friends and family, reinforcing the importance of these social groups in adolescent participation in physical activity. Close family members (e.g. father, mother and siblings) and friends are those that interact most with teenagers [15] and social groups may have the most influence on adolescents’ adopting health-related behaviors, including physical activity [26]. Parents can encourage their children to engage in physical activity through different means, such as providing sports equipment and transportation [4–7]. On the other hand, friends tend to provide greater social support through invitations and participation in physical activities [16].