-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alessio Nencini, Mauro Sarrica, Renata Cancian, Alberta Contarello, Pain as social representation: a study with Italian health professionals involved in the ‘Hospital and District without Pain’ project, Health Promotion International, Volume 30, Issue 4, December 2015, Pages 919–928, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau027

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pain is a complex issue with many different aspects concerning both sensorial and emotional experience. In recent years, the Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) network has been encouraging a new vision in health structures, with the aim of reducing any form of pain wherever possible. Following the social representation approach, we explore the concept of ‘pain’ as it is continuously redefined, constructed and shared among health professionals involved in an HPH project named ‘Hospital and District without Pain’. Three hundred and eighty-three professionals (doctors, nurses and local general practitioners referring to the hospital of Rovigo, Italy) were involved in a free association task with the aim of exploring the social representation of pain. Contents were further investigated by means of four focus group discussions. Results suggest that the representation of pain is strongly connected to medical knowledge and to functional aspects of the health practice. Other forms of pain—more relational, psychological or emotional—which do not fall within the aetiopathogenetic system of diagnosis, cannot be managed with the traditional tools of the health practice, and are not perceived to be handled with the professionals’ competence. Results will be discussed in relation to general health promotion principles and to a specific initiative on the issue of pain carried out by the HPH-Veneto network.

INTRODUCTION

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.’ (International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), 1979). It is largely acknowledged that cultural and social factors affect the meaning that this experience has not only for patients but also for health professionals, influencing practices associated with pain treatment and management (Thunberg et al., 2001; Lasch, 2002; Arntz and Claassens, 2004). In this article, we explore the representations of pain shared by doctors, nurses and GPs, with the aim of describing elements that may foster or impede the change in approaches to pain management that has been solicited by international, national and local policies (World Health Organization (WHO), 1986; Visentin, 1999).

In the medical domain, pain has been approached mainly in terms of assessment, with the focus on diagnostics and taxonomies for the development of suitable instruments of inquiry and therapy, for example by refining specific tools for pain measurement (Melzack, 1975; Katz and Melzack, 1999) or by assessing knowledge and attitudes towards its treatment (Visentin et al., 2001, 2005). However, some authors suggest that pain assessment is still lacking in terms of effective acknowledgement, monitoring and management (Hill, 1995; Rich, 1997; Brennan and Cousins, 2004; Craig, 2009), thus inviting a broader approach to the issue of pain.

Given the multifaceted nature of the theme, psychology has contributed to in understanding mainly along two directions: on the one hand, focusing on the comprehension of neuropsychological processes linked with pain (Zimmermann and Handwerker, 1984); on the other, exploring the idiosyncratic features of patients' pain, both in terms of experience (Charmaz, 1983; Werner et al., 2004; Montali et al., 2009) and expression (Prkachin and Craig, 1995; Cano and de Williams, 2010; Riva et al., 2011). As for the latter, measurement scales have been developed to assess sensorial and emotional components of pain (O'Connor, 2004). In the field of health psychology (Stroebe and Stroebe, 1994), attention has been given to the cognitive and social psychological processes that shape the concepts of health and illness, in particular as regards risk behaviour, the role of stressful agents and situations and active health promotion.

Beyond individual experience, however, the role played by social processes of knowledge construction is clearly recognizable in defining, sense-making and re-elaborating concepts related to health and illness (Flick, 2003; Capone and Petrillo, 2011). More specifically, various forms of meaning construction—such as the combination of patient–practitioner relationships, cultural beliefs and medical ideologies—contribute to producing an unwieldy and inflexible framework for thinking, acting and feeling about illness and pain (Charmaz, 1983). For example, difficulties experienced by the staff of a Swedish hospital in dealing with patients with long-standing pain have been attributed to professional ambiguity (Thunberg et al., 2001). Interviews showed the coexistence of contradictory paradigms: the bio-medical paradigm which is applied by professionals in everyday practice, and the bio-psycho-social model which is recognized by them as the ideal way of acting and thinking. This discrepancy is reflected in ambiguity of roles, perceived inconsistency between individual goals, organizational requests and even learned incapacity. Along this path, the present article presents an exploratory analysis of the social representations of pain held by professionals who confront it daily.

A social representation approach

The present study refers to the theoretical framework offered by social representations theory (Moscovici, 1961/1976). A social representation is a ‘socially elaborated and shared form of knowledge that has a practical goal and builds a reality that is common to a social set’ (Jodelet, 1989, p. 48). At the core of the theory is the idea that knowledge of relevant issues is socially constructed through communication. Social representations are linked intrinsically to group memberships, not only in face-to-face interaction but ‘in symbolic contexts as well. This is the case, for example, in certain professions, whose members share a common background in terms of theories and professional socialization’ (Flick et al., 2002, pp. 582–583). As a corollary, it is relevant to explore the different contents of the representations constructed by people belonging to different groups, but also the way contents are organized by underlying principles (e.g. good versus bad), and the relative positions that groups hold on the representational field defined by these principles.

Drawing on these premises, the social representation perspective has been widely adopted in health psychology: starting from classic research on mental illness (Jodelet, 1991) through Herzlich's (Herzlich, 1969/1973) contribution regarding the social representations of ‘health’ and ‘illness’, up to the more recent attention paid by Flick (Flick, 2000, 1998) to the different aspects which compound the representation of health by nurses, doctors and employees in the social-health sector.

The context: the ‘Hospital and District without Pain’ project

One of the most relevant changes of the last decades concerning the professional approach to pain is based on the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (World Health Organization (WHO), 1986) and the subsequent birth of the Network of Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH), ‘with the aim to reorient health-care institutions by integrating health promotion and education, disease prevention and rehabilitation services in curative care’ (http://www.who.int/healthy_settings/types/hospitals/en/). HPH should intervene at cultural and structural levels and should ‘incorporate the concepts, values, strategies, and standards of health promotion into the organizational structure and culture of the hospital’ (http://www.who.int/healthy_settings/types/hospitals/en/; see also: Pelikan et al., 2001; Pelikan et al., 2005). Italy took part in the HPH framework in the early stages, when hospitals in Milan and Padua participated in the European Pilot Hospitals Project (1991–1995) (http://www.retehphitalia.it/public/default.asp). The first regional HPH network in Italy started its activities in 1995 in the Veneto region (http://servizi.ulssasolo.ven.it/hph/).

More recently, the HPH-Veneto network has fostered an innovative project specifically oriented towards the issue of pain: ‘Hospitals and District without Pain’ (http://servizi.ulssasolo.ven.it/hph/prog03.htm). Its main aim is to reduce the rate of treatable pain in patients recovering in hospitals or at home. ‘Hospital and District without Pain’ includes hospitals where new practices and cultures are fostered, as well as communities, where GPs are invited to promote a new approach to pain (Visentin, 1999).

Starting in 2005, the Civic Hospital of Rovigo (in the north-east of Italy) set up a series of training courses for professionals on pain treatment and to expand the understanding of the issue at stake (Cancian et al., 2006). Doctors and nurses working in hospital were involved, as well as GPs working in the local communities. The courses were held in mixed groups of 20–30 people and included: (a) an introduction to the general principles of the Ottawa Charter and of the subsequent national and international guidelines; (b) several presentations on biological, clinical and psychological advances in the treatment of pain in adults and children; (c) case studies and exemplification of worst or best practice with patients; (d) the presentation of a standard ‘pain assessment ruler’ which was to be adopted by the hospital.

Aims

The present study was conducted in tandem with the training courses described above. Its aims were to explore the social representations of pain shared by experts in the health domain. We thus turned to the study of the contents and the representational field of pain, focusing on the commonalities and differences among groups of professionals: doctors, nurses and GPs.

METHODS

The study was divided into two parts: a survey and focus group discussions.

Participants

Survey

A total of 383 health professionals took part in the survey. They were doctors (43), nurses and head nurses (219) from the Civic Hospital of Rovigo, Italy, and general practitioners (121) working in the same district, all involved in the project ‘Hospitals and District without Pain’. Six participants did not declare their professional role.

Of these, 152 were men and 231 were women (6 did not declare their gender). The different categories are not uniformly distributed by gender, but the frequencies shown in Table 1 fit the general trend in hospitals in Italy and elsewhere.

Gender and professional role of the participants involved in the survey

| Professional role . | Men . | Women . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 28 | 15 | 43 |

| Nurses and head nurses | 44 | 175 | 219 |

| General practitioners | 79 | 40 | 119 |

| Total | 151 | 230 | 381 |

| Professional role . | Men . | Women . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 28 | 15 | 43 |

| Nurses and head nurses | 44 | 175 | 219 |

| General practitioners | 79 | 40 | 119 |

| Total | 151 | 230 | 381 |

Gender and professional role of the participants involved in the survey

| Professional role . | Men . | Women . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 28 | 15 | 43 |

| Nurses and head nurses | 44 | 175 | 219 |

| General practitioners | 79 | 40 | 119 |

| Total | 151 | 230 | 381 |

| Professional role . | Men . | Women . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 28 | 15 | 43 |

| Nurses and head nurses | 44 | 175 | 219 |

| General practitioners | 79 | 40 | 119 |

| Total | 151 | 230 | 381 |

Focus groups

When the training courses were concluded, four focus groups were conducted by two of the present authors within the hospital facilities. The first three focus groups were organized with professionals working at the hospital: the first one involved both doctors (one man and one woman) and nurses (four women), the second one had eight doctors (five women and three men) from different departments and the third one was conducted with seven nurses (five women and two men). A fourth focus group involved two general practitioners working in the district (both women).

Procedure

Survey

The survey was administered prior to each training course. The organizers clarified that the study was in tandem with the course and that participation in the research was on a voluntary basis. Participants were asked to answer a brief questionnaire. The instrument for the survey was conceived as an exploratory tool, mainly aimed at collecting different opinions, feelings and cognitions associated with the issue of pain. In order to provide meaningful questions to our respondents, the instrument was designed by the present authors, who are from an interdisciplinary background (social psychology, clinical psychology, anaesthesia). (While we submit that the interdisciplinary composition of our group may be a strength, we acknowledge that further investigation needs to be enriched by the perspectives of nursing professionals and GPs.) In this article, we will present data related to the first section of the survey: the free association task.

After a general introduction to the study, participants were asked to give the first five words, or brief statements, in answer to the question: ‘What comes to your mind when you think of “Pain”’?

This type of free associations task is often used when exploring the contents of social representations and their field, as that is how the contents are organized (Di Giacomo, 1981; Wagner et al., 1999).

The resulting textual corpus (1856 total words; 596 distinct words) was first processed to reduce ambiguities and data dispersion: different grammatical forms (gender, singular/plural), synonyms and semantically equivalent words were reduced to univocal lexical forms. Articles and adverbs, as well as low frequency associations (threshold = 2), were excluded from the analysis. The resulting corpus (1637 total occurrences, 124 distinct lexical forms) was organized into a contingency matrix with absolute frequency entries.

The contingency matrix (3 professional groups by 124 lexical forms) was examined via correspondence factor analysis (Benzécri et al., 1973), an exploratory method similar to principal component analysis, which was particularly suited to exploring the representational field and the ways the hospital's doctors, nurses and the GPs gave voice to it. The gender of the respondents was also entered as a supplementary variable. Correspondence factor analysis allowed us to draw the structure of associations through a graphic representation in a low-dimensional space (Lebart and Salem, 1988; Greenacre and Blasius, 1994; Clausen, 1998). Analyses were performed using the SPAD 5.6 package (CISIA).

Focus groups

Each focus group discussion lasted about 2 h and was centred on the following topics: representations of pain (e.g. ‘What does the word pain evoke in your mind?’); feedback and comments on the results concerning the free association task (e.g. ‘Data from questionnaires shows that pain evokes … How would you interpret these results?’); professional experience connected with pain (e.g. ‘Can you recall a situation in which you had to confront the pain of a patient as a professional?’); personal experiences of pain (‘Can you recall a situation in which you felt pain?’); changes in therapies for pain treatment (e.g. ‘In your opinion, what has changed in the therapies for the management of pain in recent years?’). Participants were invited to talk freely about their opinions. The questions described above were used only to orient the discussion, where necessary, towards the topics relevant for the research aims.

RESULTS

Free associations

The most frequent associations given by professionals in response to the prompt indicate that pain evokes mainly suffering, recalled by half the respondents. Feelings of fear, anxiety and unease follow, in order of decreasing frequency, bringing emotional tones to the forefront. Features of potential inability, such as isolation, depression, impotence and invalidity, are also mentioned. A remarkable role is played by the acute-chronic dichotomy (Table 2).

Free associations with pain

| Graphic forms . | Frequency . | Graphic forms . | Frequency . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering | 195 | Chronic | 33 |

| Fear | 102 | Death | 33 |

| Anxiety | 72 | Crying | 32 |

| Unease | 62 | Disease | 32 |

| Acute | 59 | Anguish | 28 |

| Isolation | 44 | Malaise | 27 |

| Depression | 42 | Intensity | 27 |

| Impotence | 39 | Help | 25 |

| Physical | 38 | Irritability | 25 |

| Disability | 37 | Unbearable | 23 |

| Graphic forms . | Frequency . | Graphic forms . | Frequency . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering | 195 | Chronic | 33 |

| Fear | 102 | Death | 33 |

| Anxiety | 72 | Crying | 32 |

| Unease | 62 | Disease | 32 |

| Acute | 59 | Anguish | 28 |

| Isolation | 44 | Malaise | 27 |

| Depression | 42 | Intensity | 27 |

| Impotence | 39 | Help | 25 |

| Physical | 38 | Irritability | 25 |

| Disability | 37 | Unbearable | 23 |

Free associations with pain

| Graphic forms . | Frequency . | Graphic forms . | Frequency . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering | 195 | Chronic | 33 |

| Fear | 102 | Death | 33 |

| Anxiety | 72 | Crying | 32 |

| Unease | 62 | Disease | 32 |

| Acute | 59 | Anguish | 28 |

| Isolation | 44 | Malaise | 27 |

| Depression | 42 | Intensity | 27 |

| Impotence | 39 | Help | 25 |

| Physical | 38 | Irritability | 25 |

| Disability | 37 | Unbearable | 23 |

| Graphic forms . | Frequency . | Graphic forms . | Frequency . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering | 195 | Chronic | 33 |

| Fear | 102 | Death | 33 |

| Anxiety | 72 | Crying | 32 |

| Unease | 62 | Disease | 32 |

| Acute | 59 | Anguish | 28 |

| Isolation | 44 | Malaise | 27 |

| Depression | 42 | Intensity | 27 |

| Impotence | 39 | Help | 25 |

| Physical | 38 | Irritability | 25 |

| Disability | 37 | Unbearable | 23 |

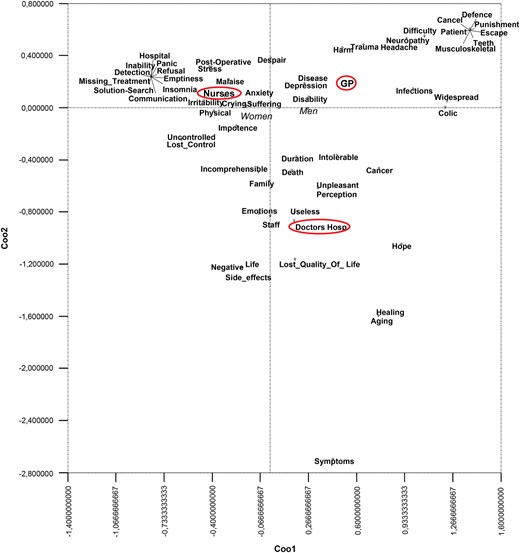

The results from correspondence analysis stress different positions held by the three groups of participants on the two dimensions of the representational field (Figure 1).

Representational field of pain, 1st and 2nd dimensions. Note: plotted terms are only those with a considerable absolute contribution on the 1st and 2nd dimensions; circled: active categorical variables; Italic: modalities of illustrative variables.

Nurses are opposed to GPs on the first dimension (X-axis; inertia = 58%); hospital doctors are opposed to GPs on the second dimension (Y-axis; inertia = 42%). (As the contingency table is composed of three columns, two factors explained 100% of the inertia (named variance in factor analysis)).

GPs tend to evoke a representation of pain aimed mainly at classifying it on the basis of typologies (e.g. colic, muscular-skeletal, widespread, infection, teeth). Some metaphorical contents are also evoked by GPs, who refer to pain as a punishment to escape or cancel. (In the illustration of the results, we retained lexical forms with absolute contribution ≥ 100/124. The absolute contribution of a point to a dimension is the proportion of inertia explained by that point; the sum of the contributions of the points to each factor is equal to 100. We present and discuss only points with higher than the average value.)

On the opposite pole, nurses refer mainly to the subjective experience of patients in pain, which is characterized by irritability, refusal, suffering, emptiness, malaise and by loss of control, panic and impotence; nurses also underline the importance of communication with patients (e.g. communication, search for a solution).

Hospital doctors give voice to the negative pole of the second dimension (Y-axis). This area of the field is characterized by mixed content that contributes more to the dimension related to the goal of reducing pain (e.g. symptoms, staff, useless, healing). However, hospital doctors share a common background both with the medical community and the hospital communities. Hospital doctors, like GPs, appear to be interested in the classification of pain: they refer to intensity and length (perception, intolerable, and duration) and to end-of-life and severe issues (aging, death, and cancer). Links with nurses are also present: doctors refer to the influence of pain on the social life of patients (e.g. lost quality of life, family, side effects, life), the need for cognition (incomprehensible) and emotional dimensions of pain (emotions and hope).

Men and women are positioned on opposite sides of the first dimension (X-axis) of the representation of pain: gender positioning overlaps largely with that of the professional roles, owing partly to the composition of our sample (doctors are mainly men while nurses are mainly women), and probably in part to different expectations in relation to social roles: men as more task-oriented, while women as more devoted to taking care of others.

Focus groups

Contents that emerged from the focus-group discussions largely overlapped with the results obtained through correspondence analysis and allowed us to explore some of the aspects connected with the representation of pain in greater depth.

Pain was described mainly in terms of suffering and discomfort, but its precise definition required the specification of the domain of competences: physical or psychological pain? Many doctors, in particular, retranslated these categories into organic versus psychological, thus suggesting an implicit etiopathogenetic vision of pain.

Pain is organic pain, the pain of the wound, it's really a medical question more than a social one. So, if somebody is in pain it's because she/he has got a broken leg or an open wound and it's something that is there as much as it can be cured.

(Anaesthetist, woman)

Our interpretation of the results emerging from the correspondence analysis was generally accepted and shared among the participants. In particular, the difference between medical and nursing staff as regards the words associated with pain (see Figure 1) was framed in the different conception of the relationship between health professional and patient. Professional identity was seen to define the boundaries of the perceived area of intervention and competence in the therapeutic relationship.

We see the side of the patient, let's call him/her patient, of the person as the physical person, the psychic, all the needs he/she has in a day, while the doctor sees it only under the therapeutic profile.

(Nurse, man)

The emerging representation of pain was loaded in terms of pragmatic and evaluative attributes: organic pain, whose origins and whose progress is known, was described as a benign and positive pain, a signal.

Also because sometimes to underestimate a pain … the thorax is wide, somebody that tells you it hurts here it hurts there … can hide some very important things. The diagnosis is important, more than taking away the pain like that, in a petty way. We have to understand how serious a situation can become.

(Emergency Unit Doctor, woman)

On the contrary, pain that does not have a clear cause, pain that eludes medical knowledge is a form of painful suffering that scares and leaves the professional without tools. Based on the consolidated epistemological principles of the medical paradigm, what is not organic is necessarily psychological and, thus, incurable by organic medicine.

… I believe that the pain was, at the end of the day, always and only of the benign kind and that certain pains that had no explanation saw me aligned with the current opinion that people were mad, depleted …

(Surgeon, man)

Another relevant dimension that emerged from the discussion was connected with the purpose and usefulness of pain: the pain that follows intentional choices or actions (like cosmetic surgery or delivery) is directed towards something, thus is useful and must be accepted.

Pain that has an aim, aimed at something, depends on the person undergoing, for example, surgery for cosmetic surgery, there are those who undergo interventions that are a bit painful, and then … there will be an improvement it's a pain you accept, a pain that all things considered you know will take you to something better.

(Anaesthetist, woman)

Therefore, the pain that must be avoided is that associated with potential non-compliance or mistakes made by the health professionals, i.e. the kind of pain that is not deserved by the patient, that is clearly identifiable in terms of cause and effect and that is under professional control.

The antinomy between direct (i.e. personal) and vicarious (i.e. professional) experiences of pain was clearly stressed by a nurse.

Once a colleague asked me: could you define what is the most bearable pain and the most unbearable? After half a day he told me, listen, it's very simple: the most bearable is that of others, the least is one's own.

(Nurse, man)

As regards the discussion over what has changed in the treatment of pain in recent years, some macro-categories of limitations were reported quite frequently by participants. Changes in pain treatment were perceived as difficult to be implemented, and the main causes were assigned to limitations in resources and means, professional culture and individual factors. More specifically, participants complained of a scarcity of multiple resources, from the lack of cutting-edge instruments to organizational issues that have consequences on the time professionals can spend on the effective management of the patient's pain.

I'm referring to a peculiar and very specific thing, which is that of new methodologies that really sweeten the pain … The new surgical means, I don't know, maybe laparoscopy, doesn't involve an incision, a cutaneous incision, surely it reduces pain. But there aren't the means. Here we don't have laparoscopy. Perhaps we will have it soon.

(Doctor, man)

You don't have the time … I see the patient coming, I see them … I give them therapy … and I send them out with something. I don't know how this something ends, there's no-body. I don't have the time to go and follow them afterwards. I've been asking for six years if I can go and follow them up, but that time isn't given to me.

(Nurse, man)

Not all problems were attributed to lack of resources. Indeed, participants often raised an issue connected to the medical culture often found in health-care structures. This culture has been described as old-fashioned and anchored to past stereotypes that are no longer effective, as compared with new knowledge and treatment techniques.

(Doctor, man) ‘We don't use morphine much …’

(Doctor, woman) ‘Exactly, since morphine I think although it's a drug which is not very expensive provokes addiction in the patient so one has to always carry on with the dose, so we try to adopt it as a last resort.

(Doctor, man) ‘Yeah, well, it's something that's been inculcated in us.

(Doctor, woman) ‘No, no of course!’.

Finally, a third category of factors that participants saw as obstructing an effective implementation of changes in pain treatment is related to the relationship between health professional and patient. An interpersonal distance with regard to the pain of the other is perceived to be necessary because the emotional load that the therapeutic relationship carries is too painful to be managed by the professional as a human being.

I do keep distances a bit 'cause I manage to be more objective, I find it hard to get closer or to be, to identify myself, I mean I'm not able to. Firstly, because otherwise I would be hurting myself and I don't want to and, secondly, because I'm more focused. I mean, I go straight to the problem, I consider it and see what to do to solve the problem.

(Nurse, woman)

CONCLUSIONS

In this article, we studied the way in which pain is represented by a convenience sample of health professionals who were involved in the HPH project called ‘Hospital and District without Pain’. The aim was to identify potentially debated issues that may help implement the suggestions proposed by the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. We thus invited doctors, nurses and coordinators from the Hospital of Rovigo to indicate, by means of a free association task with a wide group of participants, as well as focus groups, how they thought about pain and possibilities for its treatment.

Results suggest that the representation of pain is strongly nested in dimensions that are functional to the practice of healthcare. References to symbolic, debated or imaginative aspects, which can usually be found in a social representation, are scarce. The representation of pain provided by health professionals appears to be a form of shared knowledge which differs from a debated and negotiated social representation. It is well-organized, oriented towards action, and instrumental to ‘execution’ rather than to ‘generation’. The dimensions that structure the representation of pain—‘Evaluation’ versus ‘Feeling’, and ‘Intensity’ versus ‘Typology’—and the contribution of the professional roles (doctors, coordinators, nurses) in generating them are consistent with an operative system that defines and assigns areas of responsibility and competence for the treatment of pain.

Moreover, the focus group discussions suggested further dimensions of meaning that respondents used to represent pain, such as the distinction between ‘benign’ and ‘malign’ forms of pain, the cultural and organizational limitations on pain treatment and the issue of the interpersonal distance between professional and patient.

The pain that professionals refer to, the one that is called ‘benign’, is a highly protocolled and manageable kind of pain. Conversely, the pain that cannot be framed within the cognitive field of medical knowledge, and that eludes an organic explanation, needs to be anchored to personal beliefs which are loaded with meaning, emotion and evaluation (e.g. associating ‘pains that had no explanation’ with madness). In other words, the pain that is not bridled by a clear cause-and-effect relationship evokes ‘other’ forms of explanations, which draw on moral, ethical and evaluative dimensions, such as useful/useless, deserved/undeserved and benign/malign.

To sum up, our respondents mainly referred to the bio-medical paradigm, which appears coherent with their organizational structure and helps them cope with everyday practice without experiencing some of the inconsistencies reported in the literature (Thunberg et al., 2001).

However, within such a structured and in ways rigid system of knowledge, how can the WHO suggestions generate a change in practice? Is there any possibility to merge the ‘new’ solicitations for the definition of pain with a medical paradigm that is grounded in the detection of cause and the procedures for pain treatment? Answering these questions opens the discussion up mainly in two directions.

On the one hand, the macro-goal, according to which every form of pain that can be reduced or avoided must be treated, seems to be achievable within this system of knowledge. Indeed, the representation of pain provided by the health professionals involved is profoundly rooted in the attempt to achieve complete knowledge of every form of cognizable pain. Therefore, in all these cases, pain can be alleviated because the procedures of intervention may be improved, because new or more sophisticated tools may be employed or because the staff may be taught to perform better and to improve their skills in the technical operations (for these reasons, training courses have been welcomed). However, what cannot be framed within this definition of cognizable pain cannot be treated or cured and is readdressed towards other figures, e.g. the psychologist, or is redefined by other feelings, e.g. ‘fake pain’ or ‘wanting to be in the spotlight’.

On the other hand, the Ottawa Charter endorses a broader definition of pain which solicits a change in the entire system. This change should include the way professionals represent themselves and their roles, as well as the way they perform their competences. And the change should be accompanied by specific support, in order to provide doctors and nurses with adequate resources (not only on the cognitive level, but also in terms of technical tools, re-organization of tasks and re-definition of time and goals). In other words, the whole socio-technical system should be changed if professionals are to modify their area of intervention effectively with patients and colleagues, without feelings of inconsistency or incongruence.

Our results indicate that the risks of this course of action need to be carefully considered in order to foresee what the consequences of a change in the system, which regulates the relationship between health professional and patient, may be. First, as stressed by participants in the focus groups, economic and managerial resources are scarce at the moment and the discussion on how to escape the present situation is a matter of heated debate, both at the administrative and political levels, a fact which is fundamental but runs parallel the aims of the present article. Second, the current system seems to be effective for health-care practice and for the well-being of its professionals. Results showed that a psychological distance between health professional and patient is often perceived as necessary in order to manage the pathology effectively, to access the objective cause of pain and thus to best treat and cure the patient. Before asking doctors and nurses to abandon this configuration, and to focus also on other aspects connected to subjective dimensions of the pain, it is necessary to show them alternative configurations that guarantee an embracing of proper health-care and, at the same time, more idiosyncratic representations of pain. In this sense, the representation that frames the way in which practical and procedural changes are carried out makes a difference: for example, the introduction of the ‘pain assessment ruler’ in everyday procedures for patient monitoring (together with the training courses described above) has undoubtedly changed the common practices for the treatment of pain. However, if the ruler is used as a diagnostic tool which is able to offer the expert an exact knowledge of the patient's pain, then the current representation of pain will absorb the change and it will be not modified. On the contrary, if the ruler is used as a means of indirectly enhancing the communication process and taking charge of the patient's pain, a change will start not only in the practices but in the whole representation and, if sustained over time, could bring about new forms of conceptualizing the treatment of pain.

To sum up, the research revealed a variety of topics connected to pain, both explicitly and implicitly. This plurality of topics is hard to summarize in a single multifaceted representation of pain, suggesting that most likely we are talking of many different ‘pains’ using the same linguistic label. The word ‘pain’ seems to contain multiple representations that are often incommensurable, and which refer to different systems of thought oriented towards different goals. Interventions aimed at modifying health practices related to pain need to keep track of this semantic plurality, which is also a plurality of disciplinary knowledge. The committed participation in the focus groups organized in the present research supports the idea that to have some space and time during working hours to discuss and share the issues of pain is appreciated and important. It would be worth improving medical practices by increasing the consideration of relational and psychological dimensions that promote an effective interpersonal relationship (dimensions such as trust, negotiation, reception, etc.). At the same time, the results of the present study also have implications for actions directed at increasing the presence of professionals carrying knowledge of a patient oriented towards taking charge of that patient's care in the future. They might play the role of an active minority who develop and spread alternative and effective configurations of a pain treatment system.

FUNDING

The present research has been partially supported by MIUR (‘Social representations and shared knowledge: Social psychological interpretations of change’, 60A17-0900/08 ex60% Alberta Contarello). We thank the participants for their time and collaboration.