-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Madhan Balasubramanian, David S Brennan, A John Spencer, Stephanie D Short, The ‘global interconnectedness’ of dentist migration: a qualitative study of the life-stories of international dental graduates in Australia, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 30, Issue 4, May 2015, Pages 442–450, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The migration of dentists is a major challenge contributing to the oral health system crisis in many countries. This paper explores the origins of the dentist migration problem through a study on international dental graduates, who had migrated to Australia. Life-stories of 49 international dental graduates from 22 countries were analysed in order to discern significant themes and patterns. We focused on their home country experience, including stories on early life and career choice; dental student life; professional life; social and political life; travels; and coming to Australia. Our participants exhibited a commitment to excellence in earlier stages of life and had cultivated a desire to learn more and be involved with the latest technology. Dentists from low- and middle-income countries were also disappointed by the lack of opportunity and were unhappy with the local ethos. Some pointed towards political unrest. Interestingly, participants also carried prior travel learnings and unforgettable memories contributing to their migration. Family members and peers had also influenced participants. These considerations were brought together in four themes explaining the desire to migrate: ‘Being good at something’, ‘Feelings of being let down’, ‘A novel experience’ and ‘Influenced by someone’. Even if one of these four themes dominated the narrative, we found that more than one theme, however, coexisted for most participants. We refer to this worldview as ‘Global interconnectedness’, and identify the development of migration desire as a historical process, stimulated by a priori knowledge (and interactions) of people, place and things. This qualitative study has enriched our understanding on the complexity of the dental migration experience. It supports efforts to achieve greater technical co-operation in issues such as dental education, workforce surveillance and oral health service planning within the context of ongoing global efforts on health professional migration by the World Health Organization and member states.

In many developing countries, technology-driven but less problem-centric dental education has produced a group of misfit dentists, whose practice philosophies are not in line with the needs of the local population. Migration has emerged as an escape mechanism.

The competitive nature of private dental practice coupled with a geographic maldistribution of the dental workforce, and poorly managed public health systems have also contributed to the migration desire of dentists.

This qualitative study has mainly identified that the development of migration desire amongst dentists as a historical process, stimulated by a priori knowledge (and interactions) of people, place and things.

The findings of the study can be utilized to inform efforts to achieve greater technical co-operation (between developing and well developed countries) in dental education, workforce surveillance and oral health service planning within the context of ongoing policy efforts on health professional migration by the World Health Organization and member states.

Introduction

The migration of dentists into Australia is an emerging human resources for health issue with both national and international consequences. The World Dental Federation (FDI) ranks Australia as having the highest number of overseas dentists amongst the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Benzian et al. 2010; FDI 2009; OECD 2007). One of every four dentists in Australia is an overseas-qualified dentist or international dental graduate1 (Brennan et al. 2010). Historically, Australia has been an attractive destination for dentists mainly from Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (Spencer 1982). In the last decade, however, there has been a noticeable increase in dentists immigrating from developing countries and poorer regions of the world (ADC 2012; Hawthorne and HWA 2012; National Advisory Council on Dental Health 2012). ‘Source’ countries lose their educational investment made on migrating dentists, and the failure to contain the migration of dentists can be also detrimental to the health care system (Balasubramanian and Short 2011a; WHO 2006). The effect of this brain drain can in theory be ‘fatal’ in developing countries, where there is already a shortage of dentists (WHO 2006).

International dental graduates in Australia hail from over 120 countries, including all six World Health Organization (WHO) regions (Watkins and ADC 2011). The most popular entry routes are either by direct recognition of their qualification2 or further assessment through an examination (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency 2013). Postgraduate programmes in Australian dental schools and supervised practice in the public sector are other means of entry (ADC 2013). Candidates from recognized dental programmes in South Africa, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and the USA are permitted to practice in the public sector3 for up to 3 years (ADC 2013). Based on their country of qualification and preference for work and/or study, international qualifications are assessed by an accreditation and assessment body, the Australian Dental Council (ADC). Dentists in the public sector schemes and postgraduate students would still require completing the ADC process if they want to practice independently (ADC 2013). Some international dental graduates might not actively practice clinical dentistry, and be involved in research, teaching, management, or other dental or non-dental positions.

During the last few years, there has been much debate on the increase in international dental graduates immigrating through the ADC pathway (ADC 2012; Hawthorne and HWA 2012; National Advisory Council on Dental Health 2012; Watkins and ADC 2011). According to the ADC, the number of international dentist assessments rose by about 35% between 2000 and 2010 (ADC 2012). Much of this increase is due to dentists immigrating from India, Egypt, South Africa, Iran, Philippines, Indonesia, Iraq, Brazil and Sri Lanka (Watkins and ADC 2011). It is understood that around 1000 international dentist qualifications are assessed by the ADC each year, and about 200–250 are successful in this process (ADC 2012). In addition, it is also estimated about 50–75 international dental graduates enter by direct recognition of qualifications (Teusner et al. 2008).

To date, very little research has been conducted to understand why international dental graduates migrate to Australia. In New Zealand, a qualitative study that mainly looked into international dental graduate examination process also identified lifestyle and quality of life as motivating dentists to immigrate (Ayers et al. 2008). Based on a survey in Lithuania, the likelihood for emigrating elsewhere was higher amongst dentists who had relatives abroad and who did not feel personally happy (Janulyte et al. 2011). In Hong Kong, about half of the dentist workforce wanted to emigrate elsewhere, due to freedom and stability concerns after the 1997 handover to the People’s Republic of China (Corbet and Davies 1992). While much of the dentist migration research evidence has varied in scope and contribution, meaningful policy efforts to tackle this issue are incomplete without a detailed understanding on the ‘migration desire’ (or why dentists migrate, or what motivates dentists to migrate). Such an understanding dwells into the origins of the dentist migration problem. The WHO global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel (or ‘the Code’) has also stressed the importance of addressing the reasons for migration, especially in relation to health workforce development and health systems sustainability (WHO 2010). Though the Code is universal and applies to all health professions, the unique characteristics of the dental profession (based on history; dental education; predominant private practices) requires further exploration. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore the migration desire of international dental graduates in Australia. This attempt we also hope will improve international understanding on the migration of dentists.

Methods

Qualitative research methods are advantageous in dealing with descriptive data and are more useful than traditional, quantitative methods in exploratory and heuristic investigations like this study (Denzin and Lincoln 2011). This paper draws on qualitative data from a larger study of the ‘lived experiences’ of international dental graduates, who had migrated to and were resident in Australia. The methodology is pluralistic in approach (Johnson et al. 2001). It relies on phenomenological and hermeneutic inquiry to inform the collection and analysis of empirical evidence through life-stories (Annells 1996; Cohen et al. 2000). The use of these techniques enables us to capture and illuminate details on individual experiences, with the goal of creating meaning and progressing towards an interpretive understanding of the phenomena under study (Van Manen 1990).

Sampling

A sampling strategy was utilized in order to account for the heterogeneity of international dental graduate characteristics vis-à-vis gender, mode of entry and country of training. Selection of participants for the study was based on purposive and snowball sampling involving a maximum variation approach so as to enrich data quality (Patton 1990). Initial participants were identified by networking with colleagues based in dental schools, professional associations, and public services. Fifty-one international dental graduates participated in the study; 49 were included (one participant chose to withdraw from the study, and the other was not classified as internationally qualified). A list of study participants based on sampling groups is provided in Table 1.

Study participants (n)

| Sex: | Male (20); Female (29). |

| Mode of entry: | Directly registrable qualifications (5); Australian Dental Council Entrants (16); Public Sector Dental Scheme Entrants (9); Graduate Clinical Dental Students (7); Not classified elsewhere/Others* (12). |

| Country of qualification: | Bangladesh (1); Egypt (2); India (14); Indonesia (2); Iran (1); Iraq (1); Ireland (1); Macedonia (1); Malaysia (1); Nepal (1); New Zealand (2); Philippines (6); Romania (2); Saudi Arabia (1); Serbia (1); South Africa (5); Sri Lanka (1); Thailand (1); Turkey (1), United Arab Emeritus (1); United Kingdom (2); Vietnam (1). |

| WHO regions: | African Region (5); Eastern Mediterranean Region (6); European Region (8); South East Asia Region (20); Western Pacific Region (10). |

| WB income groups: | Low Income (2); Lower Middle Income (27); Upper Middle Income (13); High Income (7) |

| Sex: | Male (20); Female (29). |

| Mode of entry: | Directly registrable qualifications (5); Australian Dental Council Entrants (16); Public Sector Dental Scheme Entrants (9); Graduate Clinical Dental Students (7); Not classified elsewhere/Others* (12). |

| Country of qualification: | Bangladesh (1); Egypt (2); India (14); Indonesia (2); Iran (1); Iraq (1); Ireland (1); Macedonia (1); Malaysia (1); Nepal (1); New Zealand (2); Philippines (6); Romania (2); Saudi Arabia (1); Serbia (1); South Africa (5); Sri Lanka (1); Thailand (1); Turkey (1), United Arab Emeritus (1); United Kingdom (2); Vietnam (1). |

| WHO regions: | African Region (5); Eastern Mediterranean Region (6); European Region (8); South East Asia Region (20); Western Pacific Region (10). |

| WB income groups: | Low Income (2); Lower Middle Income (27); Upper Middle Income (13); High Income (7) |

*Participants not classified elsewhere/Others include those working as academics/researchers in Universities; doing other dental jobs such as hygienists, therapists, dental assisting, managers; non-dental students and non-dental jobs.

Study participants (n)

| Sex: | Male (20); Female (29). |

| Mode of entry: | Directly registrable qualifications (5); Australian Dental Council Entrants (16); Public Sector Dental Scheme Entrants (9); Graduate Clinical Dental Students (7); Not classified elsewhere/Others* (12). |

| Country of qualification: | Bangladesh (1); Egypt (2); India (14); Indonesia (2); Iran (1); Iraq (1); Ireland (1); Macedonia (1); Malaysia (1); Nepal (1); New Zealand (2); Philippines (6); Romania (2); Saudi Arabia (1); Serbia (1); South Africa (5); Sri Lanka (1); Thailand (1); Turkey (1), United Arab Emeritus (1); United Kingdom (2); Vietnam (1). |

| WHO regions: | African Region (5); Eastern Mediterranean Region (6); European Region (8); South East Asia Region (20); Western Pacific Region (10). |

| WB income groups: | Low Income (2); Lower Middle Income (27); Upper Middle Income (13); High Income (7) |

| Sex: | Male (20); Female (29). |

| Mode of entry: | Directly registrable qualifications (5); Australian Dental Council Entrants (16); Public Sector Dental Scheme Entrants (9); Graduate Clinical Dental Students (7); Not classified elsewhere/Others* (12). |

| Country of qualification: | Bangladesh (1); Egypt (2); India (14); Indonesia (2); Iran (1); Iraq (1); Ireland (1); Macedonia (1); Malaysia (1); Nepal (1); New Zealand (2); Philippines (6); Romania (2); Saudi Arabia (1); Serbia (1); South Africa (5); Sri Lanka (1); Thailand (1); Turkey (1), United Arab Emeritus (1); United Kingdom (2); Vietnam (1). |

| WHO regions: | African Region (5); Eastern Mediterranean Region (6); European Region (8); South East Asia Region (20); Western Pacific Region (10). |

| WB income groups: | Low Income (2); Lower Middle Income (27); Upper Middle Income (13); High Income (7) |

*Participants not classified elsewhere/Others include those working as academics/researchers in Universities; doing other dental jobs such as hygienists, therapists, dental assisting, managers; non-dental students and non-dental jobs.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted by the first author. Fieldwork extended over a six-month period, between July and December 2011. The majority of the interviews were completed in one hour or less. A semi-structured interviewing technique (also tested through a pilot study)4 was used to facilitate the diachronic narration of a participant’s life-story over time (Weiss 1994). Prior to the interview, participants were told of the researcher’s intention to revisit key events in their life story, especially those that relate to their migration to Australia. During the interview, participants were allowed to freely narrate their experiences using their own words and own terms of understanding (Patton 1990). The interviewer used prompts sparingly, but to assist a detailed discussion. Interviews were divided into two parts with the first part focused on the participant's home country experience (early career, professional, social and cultural stories),5 mainly to understand their desire to migrate to Australia. Forty-seven interviews were face-to-face interactions in which the first author travelled to a location of the participant’s choice (based in four states and a territory in Australia); two were telephone based. All interviews were digitally recorded, except for one based only on notes. Field notes were taken during and immediately after the interviews. Verbatim transcripts were prepared that were verified by the participants themselves, and by a third data entry professional.

Analysis

Audio recordings, transcripts and field notes were imported into QSR NVivo9 (QSR International 2012). Individual life story descriptions were written for each participant. This phenomenological technique helped us to study in-depth each participant’s life story, and in the process also helped us reflect on the breadth of individual experiences (Cohen et al. 2000). The home country experience was analysed through six life story segments (secondary codes): early life and career choice; dental student life; professional life; social and political life; travels; coming to Australia. Applying a hermeneutic logic, this home country experience was examined further to understand the desire to migrate (Cohen et al. 2000). This process involved interpreting events in the life-stories and exploring the hidden meaning of the lived experience (Cohen et al. 2000; Van Mahen 1990). The outcome of this analysis is presented as themes to explain the phenomenon under study. These themes are named in situ (directly using words or meanings from the participants) and/or through reflective discussion with the research team. The purpose of the names being distinct is to display emergence of the ideas/concepts from the underlying study (Denzin and Lincon 2011). Credibility was improved through peer debriefing (Collingridge and Gantt 2008). Data saturation was achieved at the life story level, thus improving the quality of data at the primary concept development stage, mainly across the three sampling groups: gender, mode of entry and country of qualification. This approach enriched findings, also improving the credibility of the research (Cutcliffe and McKenna 2002).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide. Participation was voluntary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Throughout the study, ethical standards were maintained in safeguarding participant’s privacy during sampling, storage, transcription, analysis and reporting of the findings.

Findings

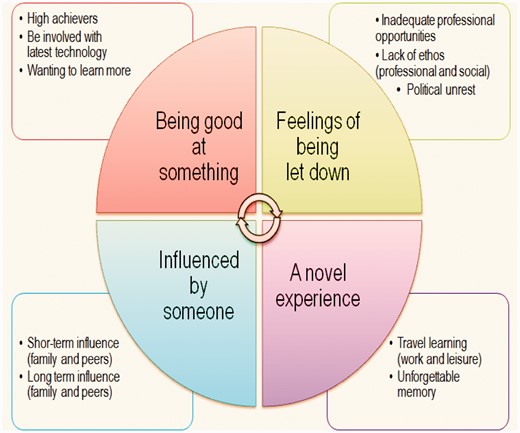

Our forty-nine participants explained their desire to migrate to Australia in terms of a wide range of considerations, which were brought together and analysed in this study in terms of four subordinate themes: ‘Being good at something’, ‘Feelings of being let down’, ‘A novel experience’ and ‘Influenced by someone’, and one superordinate theme: ‘Global interconnectedness’. This explanatory framework is illustrated in Figure 1. We address each of these subordinate themes in turn, and then address the superordinate theme that emerged from this analysis. In the description, we mainly use the WHO Regions or World Bank (WB) Income groups (classified based on country of qualification) and gender to identify participant narratives (see Table 1).

A. Being good at something

Many of our participants exhibited a commitment to excellence in earlier stages of their life. They were high achievers in school, college and professional life. This desire was exhibited through grades achieved, awards and scholarships. As a male dentist pointed out, ‘I always was a topper in my class.’ Few of our participants had also cultivated a desire to be involved with the latest technology and practice high-end advanced dentistry with the best in the world. This is shown in the narration of a female dentist from South-East Asia:

Most of our participants spoke with high regard about the quality of dentistry in Australia. They saw Australia as having some of the best professional expertise, and they indicated a desire of wanting to learn more by coming to Australia. This was put forth in the narration of a participant:I always had the ambition to go overseas – either US, UK or Australia. Whatever it is, I wanted to be practising dentistry with the latest technologies. I don’t want anything below range. I wanted to be in the top range of quality dentistry.

I came to Australia because I wanted to do my specialist training … because I wanted to be taught properly and I think back then if I did my specialist training in Indonesia. I would not be able to get you know … the proper training with the proper knowledge.

B. Feelings of being let down

Most of our participants were disappointed by the lack of good professional opportunities in their home countries. This was common in the narratives of participants from middle-income countries in the South-East Asian and Western Pacific regions. They pointed to slow career progression, fierce competition from colleagues and lesser financial incentives. As a male dentist from South-East Asia narrates:

A few of our participants (mainly from middle-income countries) were also annoyed by the lack of professional ethos in their home country systems, pointing towards issues such as job satisfaction and systemic deficiencies in care provision that has contributed to their desire to migrate. A female dentist wanted to change ‘the mentality and the work ethics so as to appreciate time and quality’ in her home country. A male dentist summed up his critique on oral health services management his home country with the words ‘all ideas are quite fair, but how it is managed is not always fair.’ Many of the participants from middle- and low-income countries highlighted at the lack of social ethos and identified several ongoing issues such as corruption, discrimination, polluted environments and bad infrastructure affecting their lifestyle and leading them to migrate. One South-East Asian female dentist sadly said, ‘corruption is everywhere corruption is too much’.When I was in the final year of graduation, it was around that time that a lot of the private colleges were about to come or were coming up that made me think … a certain scenario that so many of them will come and I felt really insecure.

Only a few of our participants, especially from countries facing some sort of ethnic war, brought out the political unrest in their home country, as making them migrate. As noted in the narration of a male dentist from Africa:

I think most white people in South Africa can see the signs. They are very patriotic, but they understand there is a big swing to migrate to Australia … All because they see the signs of poor future … I think violence is a big aspect of that. People die.

C. A novel experience

Many of our participants also pointed towards some kind of travel learning (either work or for leisure) motivating them to migrate to Australia. These participants spoke very highly of their first impressions of Australia, and how they slowly developed an interest to experience more of Australia. As a female dentist from Europe said:

Few participants also carried an unforgettable memory either through the stories from family members and/or having lived in Australia sometime in the past. As a female dentist said:During my [dental] elective, I was in [an country near Australia] for a month and then we came to Australia to work for a month … When we were doing that we did a bit of travelling around Australia and I really loved Melbourne. I never really wanted to live anywhere before apart from Scotland, until I came to Melbourne.

I am pretty much an Australian baby. I wasn't born here, but I was raised here … But then my parents took me back to Macedonia. And then I always wanted to come back. I was always dreaming Australia every single night, and that’s why I came back.

D. Influenced by someone

Most of the participants referred to being influenced by family or peers that made them come to Australia. This could be a continuous influence as a female dentist from the Western Pacific region told us:

Or this could be a short-term influence through new relationships including marriage and love. As a dentist from a middle-income country in the Western Pacific region said ‘I married an Australian, when I was on a holiday here.’ We also noted short term influences can include work acquaintances, as a male dentist from the Middle-East noted:Most of my immediate family – my parents, my brothers – they migrated from New Zealand in the late 1990s, and they have been here for while. I used to come over and spend just about every Christmas with my family here … I am the only sort of sibling left in New Zealand, so they basically made me come over to Australia

The school where I worked [in my home country] had an affiliation with a University from Australia, which introduced me to Professors [X & Y]. One year after that, the Dean at that time suggested that I come over here [to Australia] and pay a visit.

An overarching theme or worldview: Global interconnectedness

By examining the desire to migrate across the life-stories of our 49 participants, we found that even if one of these four themes had dominated their narrative, more than one theme tended to coexist with this theme. For example, a dentist of Middle Eastern origin pointed to a continued desire for excellence in his profession as the dominant narrative to migrate to Australia. Nevertheless, in the course of his life story he also recounted a novel experience in Australia, and being influenced by peers in a dental society:

We named this world view (or superordinate theme) ‘global interconnectedness’, in order to emphasise the complex nature of influences that stimulate the desire to migrate, as shown across the stretch of home country stories of our participants. Only three of the 49 interviewees did not reveal this worldview: two were female dentists who migrated due to marriage, and one participant who came to Australia as a refugee.I have been to Ireland. I did my basic dental science. I have been to the UK doing exams [Royal College]. [After my specialization]. I found the [doctorate] program in Australia very attractive.

I heard a lot about Australia. I came once. Visited a friend earlier and I liked it. I had the option to go to the US and UK, but I think I decided [Australia].

When I decided to go abroad, I was working with a dental society. The [XYZ] dental society which I think has influenced a lot of my decisions as well.

Discussion

The purpose of the paper was to explore the migration desire of international dental graduates, and thereby contribute towards health policy and planning efforts on the dentist migration problem. This qualitative study only included dentists who had migrated to and were resident in Australia. Findings might not reflect dentists who were still based in their home countries, or even those who had migrated earlier but left Australia. We interviewed dentists from 22 different countries. Though we argue that saturation of the themes was achieved during the qualitative analysis, it should be also noted that most of our participants were from lower middle or upper middle or high income WB groups. Generalizations to include countries from low income groups should proceed with some caution. Comparisons between the participant groups (gender, WHO and WB country grouping), though not meant to be exhaustive, were elaborate enough to explain the emergence of the themes. This paper concentrates on a worldview emerging from the home country experience. Credibility of the findings was improved through peer debriefing. Nevertheless, as with most qualitative studies, findings should be seen as exploratory and suggestive, rather than conclusive.

The profession of dentistry promises an attractive career option and continues to interest the top percentile of school leavers (Al-Bitar et al. 2008; Gallagher et al. 2008). In many countries, dental education is more technology-driven and less problem-centric (Field 1995). This has in some way produced a group of misfits, whose practice philosophies are not in line with the needs of the local population. We argue that more dentists graduate with an intention of practising high-end dentistry mainly in the metropolitan areas, while a large proportion of the population based in regional areas cannot afford high-end dental services. Similar arguments in physician migration research identify migration as an escape mechanism (Astor et al. 2005; Frenk et al. 2010). Due to a mismatch of competencies of health professionals to population needs, experts in medical education have called for a fundamental shift in learning with a focus on developing leadership attributes amongst students, to make them the ‘agents of change’, and more responsive to local needs (Frenk et al. 2010). The WHO has also constantly stressed the importance of adjusting training of health professionals to the needs and demands of local conditions (WHO 2006). The WHO global code for international recruitment of health personnel (Article 5.4) identifies the importance for member states to take effective measures to educate, retain and sustain health professionals that are appropriate to the specific requirements of each country (WHO 2010). The findings of this dentist migration study show a connection between dental education and migration, and provide further evidence to support the ongoing global efforts.

Over the past decade, rapid commercialization of medical and nursing education has somewhat led to an increased focus on producing professionals more suited to the Westernized world (Brush and Sochalski 2007; Kingma 2005). A comparable trend can be seen in dental education, especially in the South-East Asian and Western Pacific regions. The number of private dental colleges has increased considerably in these regions. In India, for example, 85% of the dental colleges are private establishments that share about 90% of the overall undergraduate enrolment (Mahal and Shah 2006). The number of private dental colleges in India increased from 55 in 1990 to 259 in 2013 (DCI 2013; Mahal and Shah 2006). Nevertheless, with 20,000 graduating dentists each year, India still faces the most significant scarcity of dentists in the villages (Parkash et al. 2006, 2007). Many developing countries in these regions lack clear dental workforce development, surveillance and monitoring activities. As a consequence, reliable data on the cross border migration of dentists is virtually non-existent (WHO 2006). The WHO global code for international recruitment of health personnel has supported the need for appropriate health personnel information systems, including migration of health professionals (WHO 2010). The findings of this study provide further evidence, specifically to strengthen dental workforce surveillance policy in developing countries.

Most oral health service systems are based on demand for care and provided by private dental practitioners (Kandelman et al. 2012; Petersen et al. 2005). The business trend is favourable towards urban areas, where people are more likely to be able to afford high-end dental treatment. In many countries the number of dentists wanting to practice in urban areas has produced a paradox of oversupply and less opportunity (Parkash et al. 2006). Many low and middle-income countries also face several inadequacies in public dental care (Kandelman et al. 2012; Petersen 2008). Public clinics are more likely to be understaffed and short of resources. A similar situation can be found in public medical systems, pointing towards low financial incentives, organizational problems, and resource restrictions (Chen et al. 2004). The competitive nature of private dental practice coupled with geographic maldistribution of the dental workforce and poorly managed public health systems has contributed to the desire to migrate.

The World Dental Federation (FDI) continues to play an important role in supporting the WHO Global code for international recruitment of health professionals (FDI 2006). Being a federation of national dental associations in about 135 countries, and capable of reaching over a million dental professionals, the FDI has identified the maldistribution of oral health personnel, both between and within countries, along with migration of oral health professionals as key issues to tackle in the future (Benzian et al. 2010). Other non-state players such as the International Federation of Dental Education Associations (IFDEA), a partnership of key country-based and regional educators have stressed the need for a collaborative approach to tackle dental education and regulation in an increasingly ‘flat world’ (De Vries et al. 2008; Donaldson et al. 2008). The IFDEA brings key dental education institutions across the world working together for improved knowledge transfer, and to standardise global dental education. While the findings of this study merely point out that peers and novel experiences can influence the desire to migrate, the argument that migration will lead to permanent brain drain or improve knowledge transfer or lead to economic development in source countries is controversial and beyond the scope of this study (Clemens 2007). Certainly, the impact of such partnerships in the poorer countries of the world is an issue for further research.

In comparison to physician and nurse migration, dentists face very similar socio-political and family issues. Migration due to corruption, political issues and lifestyle factors are well established (Burnham et al. 2009; Kingma 2005; Mullan 2006). Family members also play an important role in shaping the personality and in influencing key decisions of migrants (Epstein and Gang 2004). A move to a developed country is seen as a status symbol in many families, who also influence the selection of a migrant’s destination (Winchie and Carment 1989). Australia (like other developed countries such as Canada, United Kingdom and United States) is believed to be witnessing a golden age in dentistry, due to technological advances; research and teaching infrastructure; good career opportunities and attractive salaries (De Vries 2007). In addition to the enviable lifestyle, the immigration pathways are also easier for dentists (Balasubramanian and Short 2011b). This has made Australia a favourable destination for international dental graduates.

This study had traced the origins of the migration desire to very early in the migrant dentists’ life story. We argue that the development of the desire to migrate among international dental graduates accumulates from a broad range of factors, some of which are unique to the dental profession. The technology intensive dental education, vastly privatized dental education and practice are important drivers behind the migration of dentists to Australia. These dental drivers also coexist with broader health system, social and political issues. The phenomenon of global interconnectedness that emerged from the qualitative analysis suggests that the origins of the desire to migrate are complex and involves an historical aspect stimulated by a priori knowledge (and interactions) with people, place and things. Therefore, this study lends to the argument that the issue of dentist migration dwells deep in a dentist’s life-story, and has several interlacing factors that contribute to the dentists’ desire to migrate to a foreign country. Policy efforts to address the dentist migration problem should begin from this very basic understanding. To a large extent, physician and nurse migration research has highlighted the issues that contribute to health professional migration and implications for health policy and planning (Buchan and Sochalski 2004; Kingma 2005; Stilwell et al. 2004). This study has made a modest contribution by providing some additional evidence for policy efforts on dentist migration.

Due to the nature of underlying complexity in transnational flows, successful country strategies will also depend on appropriate international reinforcement (Chen et al. 2004). Tackling dentist migration policy at a national or local level also requires similar international commitment. While low- and middle-income countries can aim to address individual issues such as dental education, oral health service delivery, professional and social ethos, policies that address the problem as a whole requires a global effort. The WHO global code for international recruitment of health personnel advocates the importance of partnerships (Article 10) to strengthen the capacity of member states in implementing the objectives of the Code (WHO 2010). Considering the vastly private nature of the dental profession in many countries, the importance of such partnerships, especially with the FDI and other non-state players, cannot be underestimated.

Recent reports from the WHO point towards the designation of a national authority for facilitating information exchange on health personnel migration and the implementation of the WHO global code for international recruitment of health personnel (Siyam et al. 2013). While the report concludes that more efforts are required to strengthen implementation of the Code, it has also called for greater collaboration among state and non-state players to raise awareness, and reinforce the relevance of the Code as a potent framework for policy dialogue on ways to address the health workforce crisis (Siyam et al. 2013). The findings of this qualitative study complements ongoing efforts by the WHO and member states for greater technical co-operation on migration issues (WHO 2010; GHWA, 2012), and provide evidence for dentist migration policy to be well articulated with the mainstream health professional migration dialogue.

Conclusion

This qualitative study has enriched our understanding of the complexity of the dental migration experience. The phenomenon of global interconnectedness that has emerged in this study provides further support to the argument for improved international co-operation and cross-border collaboration to tackle the issue of dentist migration. It is to be hoped the findings of this study can be utilized to inform efforts to achieve greater technical cooperation in dental education, dental workforce surveillance, oral health service planning, and socio-political issues, within the context of the ongoing global efforts on health professional migration by the WHO and member states.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance offered by professional colleagues in dental schools, dental associations and public dental services during various stages of the fieldwork. Madhan Balasubramanian acknowledges scholarship support from the University of Adelaide. Stephanie Short acknowledges support from the Brocher Foundation Residency in Geneva. We also acknowledge the technical and administrative support received from colleagues in the Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, the University of Adelaide and Faculty of Health Sciences, the University of Sydney. We thank all the overseas qualified dentists, who spent time with us sharing their story.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Australian Dental Research Foundation (No:11ADRF_63/2010).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

1 An international dental graduate is any dentist in Australia with a primary dental qualification such as Bachelor of Dental Surgery or Bachelor of Dental Science or Doctor of Dental Surgery or Doctor of Dental Medicine or other equivalent qualifications from overseas or a foreign institution. In Australia, international dental graduates are usually referred to as overseas-qualified or overseas-trained dentists. The use of the term international dental graduate was preferred so as to be consistent with similar usage in the medical and nursing profession (i.e. international medical graduate or international nursing graduate).

2 International dentist qualifications from Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and UK are accepted for immediate registration without any further assessment.

3 Variations in the public sector scheme exist. In some states a broader list of countries qualify for the public sector schemes (DHSV 2013; NSW Health 2013).

4 The semi-structured interviewing technique was tested through a pilot study that was used as part of a methodological and training exercise for the main study (Frankland and Bloor 1999). A handful of international dental graduates, who participated in the pilot study, were able to freely comment on the nature of questions, interview process and offer suggestions either during or immediately after the interview. This process mainly provided a self-evaluation of one’s readiness, capability and commitment as a qualitative researcher and sharpened interviewer skills before the first author commenced travelling around Australia for the main study (Balasubramanian et al. 2012). None of the participants in the pilot study are included in the main study.

5 The second part of the interviews focused on settling down experience of international dental graduates in Australia—mainly including specific stories on the professional qualifying examination in Australia. This is reported elsewhere (Balasubramanian et al., in press).