-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mick Carpenter, Ben Kyneswood, From self-help to class struggle: revisiting Coventry Community Development Project's 1970s journey of discovery, Community Development Journal, Volume 52, Issue 2, April 2017, Pages 247–268, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsx002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article examines the experiences of the 1970–1975 Coventry Community Development Project in Hillfields as one of four first wave projects, and charts its avowed three stage shift from a consensual, to a pluralist and finally a class structuralist approach, developing a radical theory and practice that helped to shape the wider UK radical Community Development Project movement. While supporting the main features of the structural approach they developed in their 1975 Final Reports, we also raise critical issues that were of importance at the time, and have continuing relevance for community development in the challenging times we now face.

Introduction

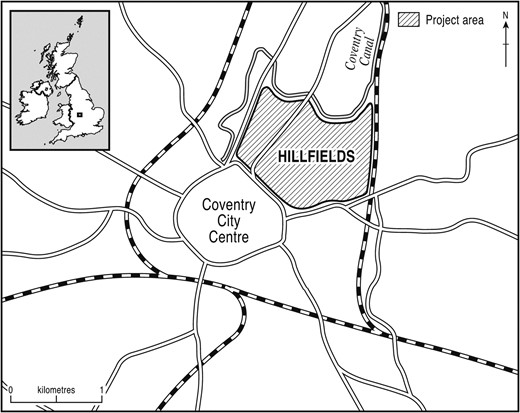

Coventry Community Development Project (CDP), situated in the inner city area of Hillfields, commenced in 1970 as one of the first four of the Government's national CDP programme – twelve local action research projects across the UK, linked to their local authorities, supported by local university research teams – seeking to turn around economically deprived areas through new ways of mobilizing local people to solve their own problems in collaboration with more responsive public services. The initial model was that local authority employed action teams would provide the catalyst for innovative community-based action and the effects would be evaluated by academic researchers from local universities. Conceived in the optimistic and confident years of the 1964–1970 Wilson government, they were implemented in the more uncertain and increasingly conflictual period of the 1970s, which saw the waning of the postwar social democratic era and the election of the Thatcher neoliberal government in 1979. The Coventry CDP ran from 1970 to 1975, and we first examine why Hillfields in Coventry came to be selected as a local site. We then chart how the CDP team sought to work with their prescribed brief, which led from initial doubts about the official emphasis on ‘self-help’ to its rejection in favour of a ‘structural class analysis’ and ‘radical institutional innovation’ in its two Final Reports of 1975 (CDP Coventry, 1975a, 1975b). We show how this was shaped by their action-research, the local circumstances they encountered, and their receptivity to the political and ideological climate of the time, These eventually led them to reject the notion that Hillfields was an isolated island of poverty amenable simply to local ameliorative action, and part of wider ‘structural’ problem of class inequality, which could only be tackled by wider systemic change. While this became the common currency of other radical CDPs, as shown by other articles in this issue on Benwell and North Shields, Coventry as first wave CDP played a leading role in pioneering this analysis and approach. We conclude with an outline assessment which, while sympathetic to the main features of the structural approach, is also critical of some of its features and implications.

The research for this article was conducted as part of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Imagine project from 2014 to 2016 (http://www.imaginecommunity.org.uk/ – accessed 12 December 2016) which has sought to develop co-productive research between universities and their mainly local communities with the aim of developing new visions and better futures. The research into CDPs was part of an ‘historical package’ uncovering past attempts to work across university-community boundaries to create new community visions, from which we believe much can be learned. Our research, involving more than seventy interviewees in total, some of which will be made available through the ESRC Data Archive, also traced the history of community interventions in Hillfields down to 2015, though we do not report on this follow-up research in this article. The research into Coventry CDP benefited considerably from our discovery of ‘lost’ documentary sources, which are now deposited with the University of Warwick Modern Records Centre (MRC) (http://mrc-catalogue.warwick.ac.uk/records/CDV – accessed 12 December 2016).

Hillfields CDP: a carefully chosen area?

Coventry was not the most obvious choice for a local experiment in tackling persistent deprivation because in the late 1960s it was regarded as a prosperous ‘Klondike’ city, characterized by high wages in the local car and engineering factories, overseen by a progressive local Labour Council that had rebuilt the city after the war and pioneered advanced forms of education and social services provision. However the national impetus to create CDPs had grown following the Midlands MP Enoch Powell's notorious anti-immigration ‘rivers of blood’ speech in 1968. This led directly to a second wave of extra support for city authorities through the central government's Urban Programme, from which CDPs were funded, which relaxed the previous funding criteria restricting it to economically deprived areas. The West Midlands was generally known to be a centre of white working class racism, and Coventry was selected within it partly because central government regarded its local authority politicians and officials as efficient and progressive and ‘chief officers…could be relied on to support the scheme enthusiastically’ (Cabinet Papers, 1968 CAB134/3291: 4). In particular, Coventry was leading the way nationally in implementing the Seebohm Report's community-focused reform of social work that was seen as crucial to the success of the CDP. It was also no accident that the local MP, Richard Crossman was a leading Labour figure and Cabinet Minister. On 7 February 1969 he wrote to Sir Charles Barratt, LL.B, Town Clerk of Coventry, inviting the city's participation as one of four phase projects in a ‘national experiment in community development in a few carefully chosen areas’. He encouraged the city to become involved in ‘what I personally feel could be a very important and useful development in the city’ (Warwick MRC Archive).

Within Coventry, a number of areas were seen as likely candidates and Claire Murphy, a sociologist employed by the Planning Department, argued that the bulldozing of central Hillfields did not create sufficient population stability for a meaningful project, as many of the deprived would be displaced. However, after internal debate Hillfields, an area close to the city centre was unanimously selected at a meeting of Chief Officers of 6 March 1969, ‘it being a blend of old and new property’ (Warwick MRC Archive). Another reason was that the Council wished to access additional Urban Aid money through which CDPs were funded to build a new secondary comprehensive school (which became known as Sidney Stringer) and a combined nursery, nursery school and play scheme in Hillfields, and including the CDP reinforced its bid. However, there is no doubt that Hillfields was regarded by the Council Planning Department and by the local press as a prime area in need of redemptive social action. There was an awareness that Council policies had not given sufficient attention to a ‘minority’ of deprived people and that Hillfields had suffered from prolonged and delayed redevelopment. However this was probably also laced with a feeling that some of the residents themselves were responsible for their problems.

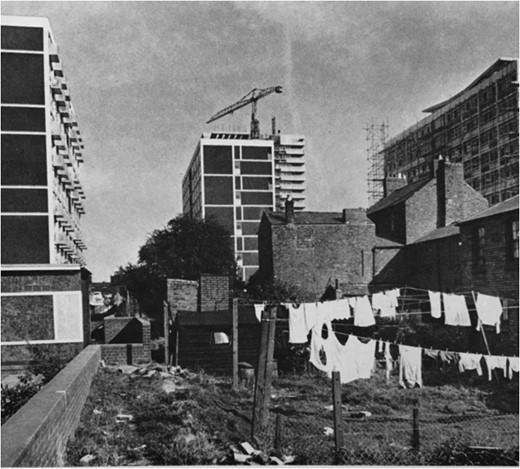

The area originated in the 1830s as a confident artisan community of silk weavers, who developed cottage industries as an alternative to the rapid spread of factory production and capitalist industry. However the turn to ‘free trade’ in the 1860 s lifted import tariffs and undermined these efforts, leading to economic decline in Hillfields and Coventry (Prest, 1960). However in the twentieth century the city rose to become a centre of armaments, car and engineering production, based on technologies of mass production. Hillfields thrived as a prosperous working class suburb within an expanding Coventry economy, even during the interwar depression. However war-time bombing, and prolonged redevelopment after the Second World War, led to an economic and reputational decline from which the area has never in fact recovered. The area became an almost classic inner city deprived area: many skilled workers and older residents moved away and it became a portal of entry for Commonwealth immigrants. Older housing was cleared, and high-rise flats erected in the 1960s with the help of central government subsidies.

In explaining why the area had been selected for ‘guinea pig aid’, the Coventry Evening Telegraph in June 1969 reported that a Councillor had described Hillfields as ‘a Dickensian slum’, a Cathedral official ‘Coventry's twilight zone’, and the police ‘Coventry's square mile of crime’. Thus different perspectives contributed to the creation of a shared official deficit of the area. However, the newspaper described the ‘vast majority’ as ‘decent, hard-working, clean-living people’ and there is ‘no reason why those living in Hillfields should not enjoy better conditions’ (CET, 17 June, 1969). In a report to his Home Office superiors, a civil servant stated that ‘the city is keen to “clean up” Hillfields’, which comprised

…a mixed population of 6000: to the “yeoman stock” of Hillfields (stable, working-class) has been added in recent years Asian and Irish immigrants…and, most recently, the socially inadequate of the city (including fatherless families, meths drinkers and prostitutes) have moved into some of the cheap or derelict housing in the area which has been the by-product of a protracted building programme (Cabinet Papers, 1970 [CAB 134/3291: 8]).

However, although Hillfields was officially regarded as an isolated ‘blemish’ on the face of the city, Coventry's status as an affluent ‘boom town’ was in fact starting to erode. Manufacturing had peaked in 1966, and the city's economic decline accelerated in the oil recession years of the 1970s and the deindustrialization that occurred under Thatcher in 1980s (Walters, 2013, pp. 235–241).

Early days of the CDP: the street-level bureaucrats get down to work

There were four key figures in the early days of the CDP in 1970. John Benington was appointed Director, and Nick Bond as Deputy, both of whom had previously worked together in Manchester. A young radical planner Paul Skelton was soon appointed to lead the work on housing improvement. From the outset they worked closely with the Reverend Harry Salmon who was not officially part of CDP but a community worker funded by the Coventry Council of Churches. All were key to the project developing a radical perspective, and provided strong unified leadership over the life of the project. They were all middle class white men. Local women were involved in secretarial roles, like Rosie Woodlock, and many women residents like Sue Kingswell became activists, both reporting in interviews in 2016 that it had been a positive life-changing experience. Edna Sexton became one of the most influential residents in the project, but could not be interviewed as she died before our project commenced. Only a small number of ethnic minority residents became actively involved, one being Ram Dehra who translated campaign materials into Urdu, and Amarjit Khera who was appointed an Assistant Community Relations Officer by the City Council and contributed to Hillfields Voice, the residents’ newsletter. In 1974, however, a significant number of Asian residents were involved in the campaign of the Five Ways Residents’ Association (FWRA, 1974) to save their streets from demolition.

Coventry was a first wave CDP project, interpreting its brief without reference to previous models, apart from the American War on Poverty (see Marris and Rein, 1967) and among the first to take a ‘radical’ approach. Around this time Lipsky's (1980) US study of officials in public services asserted that ‘street level’ workers in public services typically operated with considerable discretion, but this was magnified in the case of local CDPs, which had ambiguous aims and expectations rather than clear objectives and instructions. There were only light systems of governance, through periodic reports submitted to the Council and joint meetings with other projects and the Home Office. From the outset Benington and Bond got the Council's agreement to dispense with the prescribed local Steering Group of Councillors and representatives of key local agencies, and the two-stage separation envisaged between research and action. Local agency management would be involved only ‘when required’, so that the CDP could work closely and in accountable ways with the local community. The core team members also sought to achieve this by living in the area for the life of the project. They were employed by the Town Clerk's department of the local authority and reported regularly to a special CDP committee established by the local authority, which including leading chief officers. Though there was a small core CDP action and research team (of six people plus two secretaries) the project hired or commissioned a range of specialists for specific CDP programmes (as described below), leading the CDP to become ‘a federation of autonomous interests committed to working together on a given task for a given period’ (Bond, 1972, p. i).

The Coventry CDP area (shaded) as part of the ‘Railway Triangle’ (chequered lines), showing its proximity to city centre.

All these shifts in focus were agreed with the City Council, who from the outset accepted that tensions would emerge between it and the CDP, as it identified the needs and aspirations of residents (Warwick MRC archive). The project had the political support at key moments of the leader of the Labour Group, Councillor Arthur Waugh Senior, and active support and advice from the Assistant Town Clerk Joe Besserman, who had been a leading figure in the National and Local Government Officers Association (NALGO) nationally. Less supportive initially, however, were the Hillfields councillors, one of whom, Tom McClatchie, was Chair of the crucial Housing Committee. They saw the CDP as a threat to their local influence, and according to Arthur Waugh Junior (interview, 2015) this was partly because they had been neglectful of constituents’ interests.

Coventry CDP's three stage journey of discovery

The project's Final Report Part 1 published in 1975 (CDP Coventry, 1975a) stated that the project had gone through three main phases:

a ‘dialogue’ or consensual model involving ‘change through better communication’ between local people and agencies, up to around 1972;

a ‘social planning approach’ based on ‘pluralist’ principles, seeking ‘institutional change from within’, pinpointing blockages in agencies and pioneering interventions that worked better to tackle rather than entrench disadvantage, 1972–1974; and

a ‘political economy’ approach based on a ‘structural’ class analysis which led the project into ‘fresh political initiatives’, based on supporting community mobilization, from 1974 until the end of the project (and in fact beyond).

While we follow these stages, our research found them to be an oversimplification, the CDP team itself acknowledging things did not unfold quite as ‘neat’ in practice (CDP Coventry, 1975a, pp. 12–13). The phases are described as a learning process leading to a more radical political economic analysis, moving from a narrow neighbourhood area focus to a broader city-wide and societal focus, and a shift of ideas and strategy from exclusively community ‘self-help’, to a ‘social planning’ phase and beyond to a structural analysis and action programme. However, it is clear they had doubts from the outset about the official brief, based upon social pathology assumptions, and by 1972 Benington argued that the problems people experienced were not unique, but rather ‘a microcosm of processes that are city-wide in origin’ (Benington, 1972, p. 7). While they claimed in the Final Report to have persisted with the original model to the point that its errors and contradictions became apparent, our research found that at no time, even in this final phase to 1975, did they cease working to bring about incremental neighbourhood level improvements. Drawing on Coventry's experience, other CDPs, such as Benwell and North Shields, foreshortened the stages described here, integrating a radical stance from early on.

Phase 1: Activities of Coventry CDP

One of the first key departures of the Coventry CDP from the official national brief was to change the meaning and role of action research, particularly the clear separation between action taken and observation of it through research. The delays by Lanchester Polytechnic in appointing a Research Director enabled the CDP action team to propose that the CDP research team be based organizationally instead at Birmingham University's Institute of Local Government Studies, and later to also commission research studies on topics such as Coventry's industrial history and the role of the auto industry, and the history of Coventry's inner city housing, from radical academics at the University of Warwick. They rejected a separation between action and analysis, in favour of practical integration. As Benington put it:

We insisted that the research team for Coventry came and worked in the same building as us. We said we don't want you out in the university (Interview, 2015).

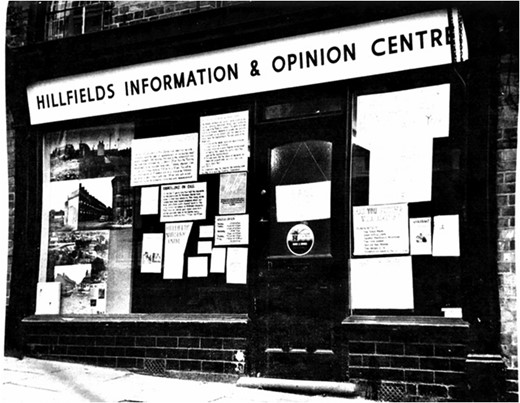

Despite their misgivings, the initial ‘dialogical’ phase from 1970 was based on the official consensual model of change in which CDP workers sought to mobilize the community, and work to identify local needs, to shape the subsequent programme of activities, and be referred upwards to local decision makers for action. There was a shared perception between the Director and the Council of a need to win the trust of the community by showing that the CDP's access to power could in the early days solve some individual problems, before focusing more appropriately on collective change. However in practice this anticipated separation between working at individual and collective levels was not maintained. There were two linked ways in which the project proceeded. First, they established a shopfront Hillfields Information and Opinion Centre (HIOC) on the main street, which served as ‘incubator’ for the whole project. Second, with Harry Salmon and other local community workers, they fostered the creation of an independent and an effective Hillfields community association, with a view to it taking over the HIOC.

The HIOC in the centre of Hillfields: the main incubator of Coventry CDP.

The second main strand of early work was to facilitate the setting up of an effective and ‘representative’ community organization that could develop and press community viewpoints. While Harry Salmon had been making efforts to turn the moribund and professionally dominated existing Hillfields Community Association (HCA) into a more representative body, Benington felt it was not fit for purpose and proposed a new organization. A compromise was reached in which the many street based organizations merged into the HCA, which also became the management committee of HIOC, control being handed over to them along with modest resources for the life of the CDP (Salmon, 1972). The ‘new look’ HCA, as well as becoming the overall ‘voice’ of residents, also exercised substantial influence over the management of the City Council's Hillfields Nursery, Play Centre and associated adventure playground schemes. Thus community workers played a significant role in shaping independent community organization, using leverage over resources. Hillfields Voice was developed as a newsletter that enabled residents to publicly air grievances and develop new initiatives.

Phase 2: Activities of Coventry CDP

In a 2016 interview with us John Benington stated that ‘mobilizing’ local people had not proven difficult, given the widespread grievances against the Council about the area's redevelopment uncovered by the HIOC scoping work. As a result, a range of priorities were developed, topped by housing and redevelopment, with low income and the needs of older people also prominent. The prominence of housing and redevelopment was primarily the result of designating most of Hillfields as a Comprehensive Development Area in 1953, which had depressed house and land prices, but planning delays over two decades had slowed demolition, resulting in ‘planning blight’. As Daryl Shaw, a resident of one of the older properties in Stockton Road and Chair of the HRS Residents’ Association put it:

Some people could not afford to buy their houses, they were still renting their houses. And they were finding it difficult to get their landlords to do anything because the landlords were saying, ‘Well, it's gonna get knocked down anyway, why should I put my money in it?’ (Interview, 2015).

Designating Hillfields as one of the city's three Comprehensive Development Areas, allowed the Council under the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act to compulsory purchase land and property, and demolish housing. However the redevelopment of the area only occurred at a snails’ pace, causing prolonged blight. The only replacements were rapidly built high-rise flats, whose construction was subsidized by central government. While this strategy was reaffirmed by the City's 1966 Review Plan (City of Coventry, 1967), national policy was about to change. The 1969 Housing Act enabled parts of Hillfields to be designated a General Improvement Area (GIA), permitting home owners to claim grants to improve properties and install basic amenities. In order to facilitate this, the Council designated a local planning officer, Ralph Butcher, to help residents through the maze of regulations and conserve the relatively few remaining Victorian streets (Interview 2016). This also became a growing area of CDP work in those streets Butcher declined to work with. CDP recruited a young planner Paul Skelton to develop a broad based programme for General Improvement Area-based housing improvement across the Hillfields project area, combining intensive community mobilization and public and resident participation, with active policy development work with the local authority planning and housing departments.

This was, however, just one among a wide range of community developments initiatives launched during Phase 2, either independently or in conjunction with local agencies, which the 1975 Final Report lists in full. The CDP team acknowledges they were able to develop ‘best practice’ with some agencies, but believed their success to be limited even where this had been facilitated by national policies. CDP appointed John Rennie to lead an innovative Community Education Programme built on the 1968 national policy of local Educational Priority Areas (EPAs) and in social services the Decentralized Innovatory Neighbourhood Team (DINT), which CDP proposed and coordinated, fitted well with the 1970 Seebohm reform of social work. However the team arguably did not grant sufficient public credit to the dynamic and innovative local leadership provided by the City Council's Director of Education Robert Aitken (see Burgess, 1986), and Director of Social Services Tom White. Thus Eric Midwinter, director of the national Educational Priority Area programme suggested that the collaboration between the Coventry CDP and Rennie made a significant contribution to innovative practice. This included pioneering work with ethnic minority children, language courses with adults, and the creation of a Hillfields Carnival which was initially founded to promote educational activities in a fun way. However, Midwinter felt the CDP took a ‘defeatist’ attitude to community education by arguing housing and employment were the prime drivers of poverty (Midwinter, 1975, p. 120). Indeed the CDP team, though regarding community educational approaches as ‘valuable in themselves’, doubted whether they could ‘counteract…the inequalities which govern the life-chances and opportunities of children from areas like Hillfields’ (CDP Coventry, 1975a, p. 30). Similarly while residents had highlighted the lack of play place for children, the team felt that this was of ‘marginal significance’ to the problems of housing, unemployment and poverty which they identified through their neighbourhood work.

This failure to acknowledge in their public reports the value of their own collaborative work with the City Council and other public agencies, also applied to other developments linked to the CDP, such as the new Sidney Stringer Community School and the combined Nursery/Nursery School/Play scheme, both funded under the government's Urban Aid programme, and in whose development the CDP team made a major contribution. Two teachers we interviewed, Val Millman and Estelle Morris (later Secretary of State for Education in the 1997 Blair Labour government) described how young professionals like themselves were attracted to work at Sidney Stringer, which combined classroom teaching and outreach work, and opened up the school to parents to use sports facilities, take courses and even provide a social club and bar where teachers and residents would mingle. Geoffrey Holroyde the first head of Sidney Stringer, highlighted the flexibility of a school which was open forty-eight weeks a year from 8 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., also at weekends, and even had occasional overnight accommodation for children who did not want to go home because of parental problems (Interview, 2016). Whereas the CDP as a whole arguably did not sufficiently engage with ethnic minority policy issues (although many ethnic minority residents were involved in its housing improvement and income rights work) Sidney Stringer certainly did, as did the Hillfields combined nursery and nursery school, the first of its kind in the UK.

Coventry Council, enthusiastic supporters of modernised social services, also pioneered the new Seebohm social services departments and worked closely with the CDP under the dynamic leadership of Tom White, Coventry's Director of Social Services, also Chair of the national Seebohm implementation group, (see Coventry Social Services, 1982). Services were swiftly devolved to neighbourhood teams, one being set up in a shopfront close to the HIOC on Primrose Hill Street. The shopfront approach undoubtedly improved accessibility and increased social workers’ involvement in the community, and the DINT project accelerated the decentralization to neighbourhoods from areas. The CDP recognized that it was possible to conduct some useful innovatory experiments with the help of a small resources fund. Local people, mainly women, were recruited from HIOC volunteers to the intake team as paid ‘street wardens’ catering for the needs of housebound older people. However, innovation was hampered by the heavy demands of statutory work, staff shortages and rapid turnover. The CDP concluded that social work by itself could not compensate for the problems of poverty and low income, resulting in the emergence of personal crisis situations in relation to issues like child care, housing, and benefit entitlement (Coventry CDP, 1975a, p. 27).

These conclusions were drawn from work that the CDP had undertaken on welfare entitlement and low income on the one hand, and housing problems on the other. Nick Bond's detailed work on neighbourhood poverty in Hillfields found that fifteen per cent of Hillfields residents in 1971 received Supplementary Benefit (means tested social security) compared to five per cent nationally, and this was due to the higher number of older people, disabled people and single parents living in the area. This higher ‘dependency’ was not due to ‘fecklessness’ but ‘related to the reasons why people are forced to claim Supplementary Benefit generally’ (Bond, 1975, p. 48). Similarly, there were a higher percentage of people claiming Unemployment Benefit in 1971, 7.8 per cent compared to 4.2 per cent in Coventry as a whole, which Bond attributed to there being higher levels of low skilled workers in Hillfields than elsewhere in the city (Bond, 1975, p. 49). In addition the work of HIOC and of Robert Zara, CDP's community lawyer appointed in April 1973, uncovered a significant number of problems with the administration of the Supplementary Benefits, including the discretionary element for ‘exceptional needs’, underpayment of benefit, lateness in payment and wrongful refusal of benefit. There was also low awareness of means tested rights by local residents, administered by a range of local authority departments. Rather than being solely a Hillfields problem, however, such problems were ‘a direct cause of hardship and anguish to thousands of Coventry's most vulnerable citizens’ (Bond, 1975b, p. 58).

An image of Hillfields in the mid-1960s: captioned ‘resurgence and renewal’ by 1966 Coventry Review Plan (City of Coventry, 1967: Photographic Section, 48).

From 1967 to 1972 the Conservatives were in control of Coventry City Council and stemmed the building of council housing, while the national Conservative government deregulated rents and imposed steep increases through so-called ‘fair’ rents under the 1972 Housing Finance Act. Thus a mixture of national and local housing and planning policies led to increased housing and environmental stress, resulting in an intensified sense of grievance among Hillfields residents. The feeling of the residents was often that they were being forced out of their homes to be rehoused in other parts of the city, on higher rents, rather than in their own community (Ginsburg and Skelton, 1975, p. 18).

Phase 3: A ‘political economy’ of Hillfields and ‘new political initiatives’

In the final phase of their work, the CDP team argued that the problems experienced by Hillfields residents were neither due to their personal failings, nor capable of being tackled by a better combination of community self-help and improved administrative connections between agencies and local people. As they put it in their Final Report:

We have not reached our conclusions through armchair research. We have seen our job as not merely to describe the situation but to help to change it (CDP Coventry, 1975a, p. 1).

As we have seen, this involved a range of interventions, including background analysis, surveys, systematic studies and practical pilot projects. Through the HIOC, the project was able to gain intelligence about the issues confronting local people, and start to tackle them in piecemeal ways. In collaboration with other local agencies, efforts were made to tackle the obstacles to providing effective help to local people, some more successful than others, though we have suggested their two final reports tended to downplay their achievements in this regard.

By moving in a radical direction, they made clear that their joint research and writing within the national CDP programme (in which John Benington played a lead role) and the research commissioned from the University of Warwick from 1973 onwards, made a significant change to their mind-set. While their own assessment of the relative lack of success of pilot projects to change local agencies led them to question a ‘pluralist’ concept of power, balancing interests through bargaining and negotiation, in favour of a ‘structural class conflict model of social change’, based on assumptions of the need to tackle ‘inequalities in the distribution of power’ (CDP Coventry, 1975a, p. 12). As we have already seen, in arriving at this conclusion, Bond (1975) had shown that low income and an inadequate social security system were the prime causes of poverty, while Ginsburg and Skelton (1975) showed that much housing dereliction, despite the age of the property and bomb damage, was not inherent but produced by planning blight. Hillfields had declined from a prosperous and ‘respectable’ area which had benefitted from the expanding economy of the interwar period, giving rise to many shops, pubs and clubs. Despite its stigmatized reputation, the CDP team found that that the Hillfields area did not have ‘an abnormal share of deviant, apathetic or “inadequate” families’ (CDP Coventry, 1975a, p. 17). The visible ‘problem’ people, they argued, were often outsiders, for example homeless men who opportunistically descended on the area to occupy derelict empty properties, and sex workers and punters who it was claimed, largely came from outside Hillfields to ply their trade, causing nuisance to residents. They had a point, but there was a danger was that such marginalized people were deemed to be ‘others’ and contrasted with the ‘real’ community.

The CDP team's central argument was that Hillfields was not unique, but emblematic of older working class areas in the north of the city, characterized by ageing housing, congestion and a decaying environment, which had led people to vote with their feet:

The better-off have largely moved out and left behind higher than average proportion of pensioners, other claimants of state benefits (the sick, the unemployed, the unsupported mother [sic]), Asian immigrants and unskilled workers (CDP Coventry, 1975a, p. 5).

In looking at the underlying ‘structural’ dynamics behind these developments, the team drew particularly on the economic research commissioned from Friedman and Carter (1975), which was subsequently expanded into an influential book (Friedman, 1977). The emerging results in 1974 had a profound effect in shaping the emerging structural analysis of the 1975 Final Report. In ways that were later influential on other CDPs (e.g. see Benwell Community Project, 1979), the research sought to locate the development of Hillfields within a historical materialist analysis of the development of Coventry's industrial economy as a whole. While the car and engineering industries expanded rapidly from the 1930s and into the post Second World War era, the numbers of skilled workers had declined, giving rise to high numbers of semi-skilled operatives. The industry had also experienced considerable fluctuations which required them to cut back quickly, leading them maintain ‘a multitude of subcontracting arrangements with smaller engineering firms’ (Friedman and Carter, 1975, p. 45). As a result, the Hillfields workforce served as a ‘reserve tank of labour’ with higher numbers of unskilled workers, who were more likely to be hired on temporary or short term contracts, paid less and be thrown out work during cyclical downturns. With considerable foresight they argued that what we would now call economic globalization was by the mid-1970 s threatening the general prosperity of Coventry, as production had peaked and the fragmented ownership of Coventry and UK car manufacturers like British Leyland did not provide access to the vast amounts of capital investment available to European and American competitors.

The CDP recognized that many of the other issues that impacted on the area were also not within the local Council's control. The national stop-go cycle of economic activity leading to restraints on public investment in times of periodic crisis was the result of central government policies. On housing, for example, the government used local authority expenditure as a prime short-term regulator of the economy, and the work of Ginsburg and Skelton (1975) had shown the results for Hillfields of the interaction between local and national housing policies. For the CDP team the Friedman and Carter analysis provided both an explanation of the current situation and a general indication of where to go next once CDP ended in 1975.

The CDP team developed a Coventry-wide forward strategy for after the end of the CDP in 1975, consistent with their analysis. First, building on the work of Nick Bond and Robert Zara, they sought Council funding for the establishment of a ‘trust’ for legal and income rights work from the City Council, and continues to this day as the Coventry Law Centre (http://covlaw.org.uk/ – accessed 30 November, 2016). On the basis of Bond's research, they also argued that computerization of local authority means tested benefits would help to improve local access to them. An educational community worker placement organization, Coventry Resources and Information Service was also established, but did not survive beyond the early 1980s.

The other significant post-CDP initiative was the Coventry Workshop, defined as ‘a local research and advisory unit’ which gained funding from Cadbury's and Gulbenkian Trusts and continued until 1987 when the remaining workers decided that it had run its course. John Benington, Paul Skelton, Richard Hallett and others founded Coventry Workshop as a small research and resource centre committed to continue working on employment and housing issues. Coventry Workshop placed particular emphasis on working closely through the trades union movement, and particularly local Trades Councils, which brought together local branches of Trades Union Congress unions. Above all they sought to work across community-worker divides, and from below against established leadership in unions and political parties. Coventry Workshop's independence as a voluntary organization meant that it was more willing to support overt conflict between community groups and the City Council and other authorities and multi-national companies like Chrysler and GEC.

Even before the end of CDP, their work took them beyond the boundaries of the CDP area, for example, by supporting campaigns such as the opposition to constructing the north-south road which has causing planning blight in the adjacent Gulson Road area (Interview, Sue Kingswell, 2016). There was also a growing willingness to support and encourage direct action by residents against the Council, the basis for resentment as we have seen being very real rather than manipulated. This involved experts in housing and public health law, such as Mel Cairns, advising residents on how to prosecute the Council for its failings under Section 99 of the 1936 Public Health Act, in numerous cases such as that brought by the Five Ways Residents’ Association in 1974, and what is more, win them (conversation with Mel Cairns and Paul Skelton, 2016).

In its time Coventry Workshop initiated a wide range of actions on deindustrialization, restructuring of the motor industry, unemployment, public services, housing, health and women's rights (Interview Jane Woddis, 2015, see also Spiegel and Perlman, 1983). These initiatives were products of their time, emanating from an awareness on the left that traditional social democracy was in retreat due to expenditure cuts and advancing deindustrialization and globalization. However, there was continuing optimism that through innovative forms of grass roots action linking community and labour struggles, a viable radical challenge could be mounted through the local state (see for example Cockburn, 1977). Thus, though Benington (1976) critiqued the extent to which local government had become ‘big business’, he did also see some benefits in a more ‘corporate’ and professional approach, with improved integration at the centre and better information of what was happening at neighbourhood level.

Coventry City Council in its response to the 1975 Final Reports acknowledged that the CDP had positively influenced its city-wide planning process. However, Hillfields had received considerable public investment which now therefore needed to be balanced across other areas in the city. It acknowledged the role of ‘planning blight’ and that ‘a policy of wholesale redevelopment is not always in the best interests of the existing residents’ and accepted the need for ‘public participation’ in considering alternative plans. It accepted the need for computerization of means tested benefits, and supported the proposed city-wide legal and income rights service. Yet while accepting that trade unions should be consulted on future industrial investment and ‘possible public ownership’ in the city, the Council had been told by central government that ‘commercial confidentiality’ set limits on the extent to which this was possible. It finally stated that ‘many of the propositions put forward by the team deal with general problems of society and involve national policies and processes’ about which it declined to comment (Comments of the Coventry City Council on the Final Report, 1975, MRC Archive).

Conclusions and outline appraisal of Coventry CDP

While it is certainly the case that initiatives like Coventry CDP need to be understood in their historical context, and care taken before criticizing them from the ‘enormous condescension of posterity’ (Thompson, 1963, p. 12) , we equally believe that it is valid to evaluate their contribution, as part of an effort to consider the implications for our own times. We start from respect and admiration of what Coventry CDP achieved in the relatively short period in which it operated, and the commitment shown by community workers, residents and City Council partners. The learning journey that the CDP team took from self-help to class analysis then helped to shape the radical CDP movement as a whole, and indeed a broader left politics linking communities, trade unions and local state agencies, uniting economic and social policy. We agree with the Coventry CDP team's emphasis on class and political economy, and their argument that the fortunes of one part of a city cannot be understood in isolation from the whole, and how this in turn is located within a wider national and global framework. As Shaw and Mayo (2016) argue, class has an urgent contemporary relevance for community development, despite the shift away from such ‘grand narratives’ and emphasis on a pluralist politics of identity and diversity. However, although we would endorse the centrality given to a structural analysis and politics of class, we would assert that this needs to be linked to a wider intersectional analysis of how, in the lives of individuals, communities, cities and nations, class and other social divisions interrelate. Rather than polarized as alternatives, there is no reason in principle why a structural and processual politics of class divisions and identities cannot be brought together with consideration of a wider range of issues such as gender, ‘race’/ethnicity, disability, age and generation. Indeed, the dangers of a rupture between identity and class politics are becoming only too apparent in the growth of right wing populist movements that seek to harness the ‘left behind’ white working class, most notably in 2016 through the votes in the UK to leave the European Union and in the USA to elect Donald Trump as President.

Therefore in criticizing the singular emphasis on class politics characteristic of Coventry CDP – and by implication, the wider CDP movement – we are not seeking to assert a different set of concerns around issues such as gender, ethnicity, disability and sexuality, but rather an integrated approach in which class and capitalism remain salient. In this respect the work of Wacquant (1996) is promising, because it focuses on intersections between class and ‘race’ in the ways that the spatial inequalities experienced intensely in particular geographical areas have been reproduced over time. Of course, we must remember that in the early 1970s context, when Coventry CDP was getting under way, the second wave of the feminist movement was only just emerging. Nevertheless, there is a complete silence on gender in the 1975 Final Reports and associated research papers, including Friedman and Carter's influential political economy analysis. Yet, there was a large presence of women in the Coventry labour force, and women trade unionists in Coventry were becoming active on issues such as equal pay, including a spontaneous strike by 200 women GEC workers in 1973. Remarkable also is the lack of attention given by the CDP team to the issue of ‘race’/ethnicity. To be fair, the reports do highlight the significant presence of ‘immigrants’ as a disadvantaged presence within the area, but only as footnotes to the main class narrative. In terms of daily practice, we found evidence that the project helped many women and migrants, for example through the housing improvement work, HIOC and legal casework, but not through an explicit recognition of gender or ethnic disadvantage as policy issues. This was at a time when such issues were becoming significant issues in Coventry and the West Midlands, with right wing organizations like the National Front seeking to mobilize against the influx of recent waves of Asian immigrants expelled from Uganda and Kenya.

Above all we admire the efforts to connect the micro and macro that runs through the work of Coventry CDP and which then fed into the wider CDP movement and publications, which creates possibilities for action at a number of levels. Our research indicates, however, that at the analytical level the role attributed to structural forces was at times overplayed and the possibilities for ameliorative action and collaboration at the local level unconsciously underestimated. Thus while the CDP team self-criticized the first two phases of their local work, this may have had more positive effects than they publicly acknowledged. In the process we mainly hear the voice of the CDP team, rather than their other agency partners, The voices of community members themselves, though visible in newsletters such as Hillfields Voice are largely absent from policy publications, and the team largely speak on their behalf. A notable exception is the Future for Five Ways report co-produced by residents and CDP team members (FWRA, 1974), and the case study of the Gosford Green Residents Association (MRC Archive, University of Warwick).

We believe that our findings have continuing relevance for policy and practice, in that it is neither necessary or helpful to polarize identity against class politics, or ameliorative against transformative action. Our hope, therefore, is that research into the actual practice of CDPs such as Coventry, might help facilitate a re-evaluation of the positive but sometimes problematic legacy of CDPs, in order to help foster a new synthesis between reformist and radical community development appropriate to our challenging times.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks are due to John Benington for his helpful comments on the draft version of this article. Also to Dr Alice Mah, who played a key role in developing the Hillfields CDP research, and also made helpful comments on the draft version of this article.

Funding

The research for this article was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) ‘Imagine – Connecting Communities through Research’ project (grant no. ES/K002686/2).

References

Author notes

Mick Carpenter was lead researcher for the Hillfields CDP research and is Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at the University of Warwick. He has been active in community action and research in Coventry since the 1970 s.

Ben Kyneswood was Research Fellow for the Hillfields CDP research and is currently Lecturer in Sociology at Coventry University.