-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liat Ayalon, Ohad Green, Live-In Versus Live-Out Home Care in Israel: Satisfaction With Services and Caregivers’ Outcomes, The Gerontologist, Volume 55, Issue 4, August 2015, Pages 628–642, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt122

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The present study provides a preliminary examination of the relationship between the type of home care services (live-in vs. live-out; i.e., round the clock vs. several hours per week), the caregiver’s satisfaction with services, and the caregiver’s burden, distress, well-being, and subjective health status within the conceptual framework of caregiving outcomes proposed by Yates and colleagues (Yates, M. E., Tennstedt, S., & Chang, B. H. [1999]. Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 54, P12 –P22. doi:10.1093/geronb/54B.1.P12).

A random stratified sample of family caregivers of older adults more than the age of 70 who receive live-in (442) or live-out (244) home care services through the financial assistance of the National Insurance institute of Israel was selected. A path analysis was conducted.

Satisfaction with services was higher among caregivers under the live-in home care arrangement and positively related to well-being. Among caregivers, live-in home care was directly associated with higher levels of subjective health and indirectly associated with better well-being via satisfaction with services.

The present study emphasizes the potential benefits of live-in home care services for caregivers of older adults who suffer from high levels of impairment and the importance of assessing satisfaction with services as a predictor of caregivers’ outcomes.

There is an overarching consensus concerning some of the negative consequences of caregiving to older adults (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). These include increased burden and burnout, higher levels of depression, lower quality of life, and worse health status (Mausbach, Chattillion, Roepke, Patterson, & Grant, 2013). There is also some evidence to associate caregiving with a higher mortality risk (Fredman et al., 2010; Schulz & Beach, 1999). The negative consequences associated with caregiving are important not only in their own right but in their association with the care recipient’s outcomes. Specifically, past research has shown that the caregiver’s burden and depression put the older care recipient at a risk for early institutionalization (Gallagher et al., 2011). The caregiver’s burden is also a prominent risk for elder maltreatment (Johannesen & LoGiudice, 2013).

A variety of theoretical models have been offered to account for the negative effects associated with caregiving (Lawton, Moss, Kleban, Glicksman, & Rovine, 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990; Yates, Tennstedt, & Chang, 1999). One of the most prominent models proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999) suggests that the relationship between primary stressors, such as the care recipient’s functional or cognitive impairment, and the caregiver’s outcomes is mediated through different variables including the caregiver’s primary appraisal of the situation (e.g., the amount of informal support given by family and friends) and the use of formal (paid) support. Secondary appraisal in the form of the caregiver’s subjective burden and distress is considered a mediator of the relationship between the caregiver’s objective burden and his or her quality of life and well-being (for additional studies that have used the model, see Son et al., 2007; Yates et al., 1999; Zarit, Kim, Femia, Almeida, & Klein, 2013). The caregiver’s characteristics, such as age, gender, or financial status are also included in the model as potential covariates (Casado & Sacco, 2013; Chappell & Reid, 2002; Lawton et al., 1991; Yates et al., 1999).

We use the conceptual model proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999) in order to examine more closely the role of live-in versus live-out home care services (i.e., round the clock vs. several hours per week) and satisfaction with these services in relation to the caregiver’s burden, distress, well-being, and subjective health status. An advantage of using this model over other models that attempt to account for the caregiver’s outcomes stems from the fact that the model distinguishes between the care recipient’s functional status and the caregiver’s response. As a result, the caregiver’s burden is viewed as a secondary appraisal, rather than as a primary stressor (Yates et al., 1999). Another advantage stems from the fact that in contrast to other models (e.g., Pearlin et al., 1990), the model proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999) and adapted by Chappell and Reid (2002) pays less attention to the coping style of the caregiver and more attention to formal and informal service use, which are the foci of the present study.

There is considerable interest in the development and implementation of services that can ease the burden associated with caregiving among caregivers of older care recipients. Various studies have shown that adult day centers, telehealth care, and home care services reduce the caregiver’s stress and improve the caregiver’s psychological well-being (Chiang, Chen, Dai, & Ho, 2012; Jepson, McCorkle, Adler, Nuamah, & Lusk, 1999; Zarit, Stephens, Townsend, & Greene, 1998), with a recent review concluding that respite services and programs for psychosocial interventions are the main methods used (Garcés, Carretero, Ródenas, & Alemán, 2010). Nevertheless, evidence for the efficacy of these various interventions in reducing the caregiver’s burden is still inconclusive (Garcés et al., 2010).

In contrast to the burgeoning body of research on the relationship between the caregiver’s service use and subjective burden, the literature on the caregiver’s satisfaction with services is limited. Satisfaction with services is referred to as an important component related to the quality of the services and patient empowerment (Guerriere, Zagorski, & Coyte, 2013; Lowe, Lucas, Castle, Robinson, & Crystal, 2003; McAllister, Dunn, Payne, Davies, & Todd, 2012). Nonetheless, only a select number of studies has addressed the issue of the caregiver’s satisfaction as a potentially important variable (e.g., Judge et al., 2011; Pillemer, Hegeman, Albright, Henderson, & Morrow-Howell, 1998).

Past research has shown that the care recipient’s functional and cognitive impairments are negatively associated with the caregiver’s satisfaction with services (Ayalon, 2011; Karlsson, Edberg, Jakobsson, & Hallberg, 2013; Rabiner, 1992; Savard, Leduc, Lebel, Beland, & Bergman, 2006). The caregiver’s relationship to the care recipient is also related to satisfaction with services, with some arguing that spouses tend to report higher levels of satisfaction (Savard et al., 2006) and other researchers suggesting that friends tend to be more satisfied (Kietzman, Benjamin, & Matthias, 2008). In addition, the type of services also plays a role, with caregivers reporting higher levels of satisfaction with certain services, such as live-in home care compared with live-out home care (Iecovich, 2007). In contrast to the burgeoning body of literature on predictors of the caregiver’s satisfaction with services, potential outcomes associated with the caregiver’s satisfaction, such as the caregiver’s burden, well-being, and quality of life have received only minimal attention (e.g., Foster, Brown, Phillips, & Carlson, 2005; Petrovic-Poljak & Konnert, 2013).

The Israeli Case

Israel offers a unique perspective on the care of older adults. On the one hand, older Israelis enjoy a relatively strong family support system (Lavee & Katz, 2003) and on the other hand, they also enjoy the relatively generous support of the welfare system in the country. Enacted in 1988, the Long-Term Care (LTC) community law was specifically designed to allow older adults to age in the community for as long as they possibly can (Iecovich, 2012). Under this law, older adults can choose between a variety of subsidized services, including adult day care centers, home care services, incontinence services, laundry services, or an emergency button. Currently, the law supports about 17% of all older Israelis; with 98% of them receiving partial financial support in the form of home care services, and 69% of these people receive home care as the only service. A little over one third of all home care services are provided by live-in migrant home care workers from the Far East or Eastern Europe and the remaining two thirds are provided by live-out Israeli home care workers. Eligibility for home care is a function of age, financial status, and functional impairment (National Insurance Institute of Israel, 2011).

In Israel, both live-in migrant home care workers and live-out Israeli home care workers are paraprofessionals. They are responsible for the provision of personal care and light household work. The stay of the live-in migrant home care worker in the country is considered temporary, and the worker is expected to return to his or her home country within 63 months or when the care recipient dies (whichever is longer). In contrast, live-out home care workers are primarily Israeli citizen, with a substantial portion of the workers coming from the former Soviet Union as part of the large immigration wave of Jews in the early 1990s.

Whereas the Israeli government subsidizes live-out home care services for up to 22hr of weekly care (depending on the level of impairment of the care recipient), only a portion of the salary of the live-in home care worker is subsidized by the government (a maximum of 18hr of weekly care), and the remaining salary (a few hundred dollars per month) is paid by the care recipient and his or her family (Natan, 2011). The distinction between the two types of home care services is primarily based on the care recipient’s level of impairment, with only the most impaired care recipients being eligible to employ a live-in home care worker (Heller, 2003; Natan, 2011).

Not unique to Israel, research has identified characteristics at the care recipient and caregiver levels that are associated with home care service use. As expected, need is a major driving force behind home care service use, with those older adults at higher levels of impairments receiving more hours of home care (Henton, Hays, Walker, & Atwood, 2002). Financial status is another determinant of home care service use, with research showing that when financial support for home care services declines, older adults are less likely to use home care and more likely to rely on acute care (D’Souza, James, Szafara, & Fries, 2009). In addition, the availability of informal care provided by family members is also associated with lower uses of home care services (Crocker Houde, 1998).

The present study adapts the conceptual model proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999) in order to compare caregivers of older adults who receive live-in migrant home care services with those who receive live-out Israeli home care services on several variables of potential importance to both caregivers and care recipients alike, including satisfaction with home care services, the caregiver’s burden associated with the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), the caregiver’s distress over neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPSY), the caregiver’s subjective health perceptions, and the caregiver’s well-being. Using this theoretical model, we also examine whether the association of type of home care services with the caregiver’s subjective burden, distress, well-being, and subjective health status is mediated by the caregiver’s satisfaction with services.

This study is timely because of ongoing efforts by the Israeli government to reduce or limit the number of live-in home care workers in the country, which is due to the fact that this type of caregiving arrangement relies almost solely on migrant workers. As such, this study provides a direct response to recent calls that have argued that, currently, Israel offers only two very extreme alternatives to older adults who wish to remain in their home: either several hours of home care provided by an Israeli home care worker or round-the-clock care provided by a migrant home care worker. This has led some researchers to argue that the current system may not adequately support those individuals who may require more than several hours of care per day but not necessarily need round-the-clock care (Asiskovitch, 2013; Natan, 2011). Given the fact that reliance on home care services is not unique to Israel but rather represents a common phenomenon in the developed world (Onder et al., 2007; Penning, 2002), evaluating the two types of home care services should provide important insights to policy makers and health care professionals worldwide.

The present study compared these two caregiving alternatives by focusing on a random sample of individuals that were identified by the National Insurance Institute of Israel (NIII) as needing high levels of care and thus were eligible to employ a live-in home care worker; yet, some selected to rely on live-out care and others opted for live-in care. To date, we were able to identify only one prior research study that compared the two caregiving arrangements. That study found higher levels of satisfaction among live-in home care recipients compared with live-out home care recipients (Iecovich, 2007). Hence, the present study provides a preliminary examination of the relationship between type of home care services, the caregiver’s satisfaction with services and the caregiver’s burden, distress, well-being, and subjective health status within the conceptual framework proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999).

Methods

The study was funded by the NIII and approved by the ethics committee of Bar Ilan University. A random stratified sample of older adults more than the age of 70 who live in the center of Israel (2,014) was drawn from the national pool of older adults who receive financial assistance from the NIII under the LTC community law. Eligibility criteria for inclusion were as follows: the care recipient is 70 or more, lives in the community in the center of Israel, speaks Hebrew or Russian, meets the eligibility criteria for employing a migrant home care worker (as only the most impaired older adults are eligible to employ a migrant home care worker), and employs a home care worker. Corresponding primary caregivers based on the records of the NIII or based on the reports of the care recipients were invited to participate, provided they spoke Hebrew or Russian. Of the original sample (2,014), 570 family members were noneligible due to the death of the older adult (362), lack of home care use (154) or ineligibility (54), and 755 were not interviewed (8 due to physical illness, 467 refused to participate, 216 could not be reached, 42 agreed but were not interviewed due to project termination, 22 unknown status). The present study concerns 686 family members, who were interviewed (47.5% response rate) between May, 2012 and February, 2013. Table 1 outlines the demographic characteristics of the sample.

| . | Total sample (686) . | Live-out (244) . | Live-in (442) . | t/χ2 . | df . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipients’ characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 83.8 (6. 4) | 82.1 (6.2) | 84.8 (6.3) | 5.33 | 683 | <.001 |

| Gender | .64 | 1 | .43 | |||

| Woman | 444 (64.7%) | 155 (65.1%) | 289 (68.2%) | |||

| Primary stressors | ||||||

| ADL/IADL impairment (0–12) | 8.7 (2.70) | 7.3 (2.85) | 9.6 (2.26) | 11.73 | 684 | <.001 |

| NPSY (0–12) | 3.1 (2.83) | 3.4 (3.02) | 2.9 (2.72) | −2.45 | 675 | .01 |

| Supervision needs (0–9) | 3.8 (4.44) | 3.9 (4.41) | 3.8 (4.43) | −.33 | 683 | .74 |

| Additional formal service use | ||||||

| Attends adult day care center | 89 (13.0%) | 43 (17.6%) | 46 (10.4%) | 7.18 | 1 | <.01 |

| Caregivers’ characteristics | ||||||

| Affiliation to care recipient | 10.67 | 2 | .005 | |||

| Child | 493 (71.9%) | 158 (64.8%) | 335 (75.8%) | |||

| Spouse | 120 (17.5%) | 57 (23.4%) | 63 (14.3%) | |||

| Other | 73 (10.6%) | 29 (11.9%) | 44 (10%) | |||

| Age | 60.6 (11.5) | 61.0 (12.2) | 60.4 (11.1) | −.62 | 681 | .54 |

| Age of child caregivers | 56.6 (7.76) | 55.5 (7.85) | 57.2 (7.67) | 2.32 | 489 | .02 |

| Age of spouse caregivers | 78.0 (6.3) | 77.3 (5.9) | 78.6 (6.6) | 1.13 | 118 | .26 |

| Age of other caregivers | 59.0 (12.9) | 58.8 (12.6) | 59.1 (13.3) | .09 | 70 | .93 |

| Gender | 2.63 | 1 | .12 | |||

| Woman | 469 (69.1%) | 175 (72.9%) | 294 (62.7%) | |||

| Financial status | 25.9 | 1 | <.001 | |||

| Can’t make ends meet | 141 (21.0%) | 76 (31.8%) | 65 (15.1%) | |||

| Lives with care recipients | 202 (29.7%) | 109 (44.9%) | 93 (21.2%) | 41.8 | 1 | <.001 |

| Primary appraisal | ||||||

| Assistance in ADLs/IADLs | 3.9 (3.34) | 4.7 (3.46) | 3.4 (3.17) | −4.99 | 684 | <.001 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Satisfaction with services (1–5) | 4.2 (.73) | 3.8 (.75) | 4.4 (.65) | 9.52 | 676 | <.001 |

| Secondary appraisal | ||||||

| Subjective burden (0–48) | 5.9 (9.17) | 7.7 (10.27) | 4.9 (8.34) | −3.94 | 684 | <.01 |

| Distress due to NPSY (0–5) | 2.1 (1.81) | 2.2 (1.82) | 2.0 (1.80) | −1.92 | 684 | .06 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Well-being (0–5) | 3.2 (1.14) | 3.0 (1.24) | 3.3 (1.07) | 2.83 | 678 | .005 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | 2.8 (1.07) | 2.5 (1.07) | 3.0 (.98) | 6.08 | 678 | <.001 |

| . | Total sample (686) . | Live-out (244) . | Live-in (442) . | t/χ2 . | df . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipients’ characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 83.8 (6. 4) | 82.1 (6.2) | 84.8 (6.3) | 5.33 | 683 | <.001 |

| Gender | .64 | 1 | .43 | |||

| Woman | 444 (64.7%) | 155 (65.1%) | 289 (68.2%) | |||

| Primary stressors | ||||||

| ADL/IADL impairment (0–12) | 8.7 (2.70) | 7.3 (2.85) | 9.6 (2.26) | 11.73 | 684 | <.001 |

| NPSY (0–12) | 3.1 (2.83) | 3.4 (3.02) | 2.9 (2.72) | −2.45 | 675 | .01 |

| Supervision needs (0–9) | 3.8 (4.44) | 3.9 (4.41) | 3.8 (4.43) | −.33 | 683 | .74 |

| Additional formal service use | ||||||

| Attends adult day care center | 89 (13.0%) | 43 (17.6%) | 46 (10.4%) | 7.18 | 1 | <.01 |

| Caregivers’ characteristics | ||||||

| Affiliation to care recipient | 10.67 | 2 | .005 | |||

| Child | 493 (71.9%) | 158 (64.8%) | 335 (75.8%) | |||

| Spouse | 120 (17.5%) | 57 (23.4%) | 63 (14.3%) | |||

| Other | 73 (10.6%) | 29 (11.9%) | 44 (10%) | |||

| Age | 60.6 (11.5) | 61.0 (12.2) | 60.4 (11.1) | −.62 | 681 | .54 |

| Age of child caregivers | 56.6 (7.76) | 55.5 (7.85) | 57.2 (7.67) | 2.32 | 489 | .02 |

| Age of spouse caregivers | 78.0 (6.3) | 77.3 (5.9) | 78.6 (6.6) | 1.13 | 118 | .26 |

| Age of other caregivers | 59.0 (12.9) | 58.8 (12.6) | 59.1 (13.3) | .09 | 70 | .93 |

| Gender | 2.63 | 1 | .12 | |||

| Woman | 469 (69.1%) | 175 (72.9%) | 294 (62.7%) | |||

| Financial status | 25.9 | 1 | <.001 | |||

| Can’t make ends meet | 141 (21.0%) | 76 (31.8%) | 65 (15.1%) | |||

| Lives with care recipients | 202 (29.7%) | 109 (44.9%) | 93 (21.2%) | 41.8 | 1 | <.001 |

| Primary appraisal | ||||||

| Assistance in ADLs/IADLs | 3.9 (3.34) | 4.7 (3.46) | 3.4 (3.17) | −4.99 | 684 | <.001 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Satisfaction with services (1–5) | 4.2 (.73) | 3.8 (.75) | 4.4 (.65) | 9.52 | 676 | <.001 |

| Secondary appraisal | ||||||

| Subjective burden (0–48) | 5.9 (9.17) | 7.7 (10.27) | 4.9 (8.34) | −3.94 | 684 | <.01 |

| Distress due to NPSY (0–5) | 2.1 (1.81) | 2.2 (1.82) | 2.0 (1.80) | −1.92 | 684 | .06 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Well-being (0–5) | 3.2 (1.14) | 3.0 (1.24) | 3.3 (1.07) | 2.83 | 678 | .005 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | 2.8 (1.07) | 2.5 (1.07) | 3.0 (.98) | 6.08 | 678 | <.001 |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

| . | Total sample (686) . | Live-out (244) . | Live-in (442) . | t/χ2 . | df . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipients’ characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 83.8 (6. 4) | 82.1 (6.2) | 84.8 (6.3) | 5.33 | 683 | <.001 |

| Gender | .64 | 1 | .43 | |||

| Woman | 444 (64.7%) | 155 (65.1%) | 289 (68.2%) | |||

| Primary stressors | ||||||

| ADL/IADL impairment (0–12) | 8.7 (2.70) | 7.3 (2.85) | 9.6 (2.26) | 11.73 | 684 | <.001 |

| NPSY (0–12) | 3.1 (2.83) | 3.4 (3.02) | 2.9 (2.72) | −2.45 | 675 | .01 |

| Supervision needs (0–9) | 3.8 (4.44) | 3.9 (4.41) | 3.8 (4.43) | −.33 | 683 | .74 |

| Additional formal service use | ||||||

| Attends adult day care center | 89 (13.0%) | 43 (17.6%) | 46 (10.4%) | 7.18 | 1 | <.01 |

| Caregivers’ characteristics | ||||||

| Affiliation to care recipient | 10.67 | 2 | .005 | |||

| Child | 493 (71.9%) | 158 (64.8%) | 335 (75.8%) | |||

| Spouse | 120 (17.5%) | 57 (23.4%) | 63 (14.3%) | |||

| Other | 73 (10.6%) | 29 (11.9%) | 44 (10%) | |||

| Age | 60.6 (11.5) | 61.0 (12.2) | 60.4 (11.1) | −.62 | 681 | .54 |

| Age of child caregivers | 56.6 (7.76) | 55.5 (7.85) | 57.2 (7.67) | 2.32 | 489 | .02 |

| Age of spouse caregivers | 78.0 (6.3) | 77.3 (5.9) | 78.6 (6.6) | 1.13 | 118 | .26 |

| Age of other caregivers | 59.0 (12.9) | 58.8 (12.6) | 59.1 (13.3) | .09 | 70 | .93 |

| Gender | 2.63 | 1 | .12 | |||

| Woman | 469 (69.1%) | 175 (72.9%) | 294 (62.7%) | |||

| Financial status | 25.9 | 1 | <.001 | |||

| Can’t make ends meet | 141 (21.0%) | 76 (31.8%) | 65 (15.1%) | |||

| Lives with care recipients | 202 (29.7%) | 109 (44.9%) | 93 (21.2%) | 41.8 | 1 | <.001 |

| Primary appraisal | ||||||

| Assistance in ADLs/IADLs | 3.9 (3.34) | 4.7 (3.46) | 3.4 (3.17) | −4.99 | 684 | <.001 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Satisfaction with services (1–5) | 4.2 (.73) | 3.8 (.75) | 4.4 (.65) | 9.52 | 676 | <.001 |

| Secondary appraisal | ||||||

| Subjective burden (0–48) | 5.9 (9.17) | 7.7 (10.27) | 4.9 (8.34) | −3.94 | 684 | <.01 |

| Distress due to NPSY (0–5) | 2.1 (1.81) | 2.2 (1.82) | 2.0 (1.80) | −1.92 | 684 | .06 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Well-being (0–5) | 3.2 (1.14) | 3.0 (1.24) | 3.3 (1.07) | 2.83 | 678 | .005 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | 2.8 (1.07) | 2.5 (1.07) | 3.0 (.98) | 6.08 | 678 | <.001 |

| . | Total sample (686) . | Live-out (244) . | Live-in (442) . | t/χ2 . | df . | p value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipients’ characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 83.8 (6. 4) | 82.1 (6.2) | 84.8 (6.3) | 5.33 | 683 | <.001 |

| Gender | .64 | 1 | .43 | |||

| Woman | 444 (64.7%) | 155 (65.1%) | 289 (68.2%) | |||

| Primary stressors | ||||||

| ADL/IADL impairment (0–12) | 8.7 (2.70) | 7.3 (2.85) | 9.6 (2.26) | 11.73 | 684 | <.001 |

| NPSY (0–12) | 3.1 (2.83) | 3.4 (3.02) | 2.9 (2.72) | −2.45 | 675 | .01 |

| Supervision needs (0–9) | 3.8 (4.44) | 3.9 (4.41) | 3.8 (4.43) | −.33 | 683 | .74 |

| Additional formal service use | ||||||

| Attends adult day care center | 89 (13.0%) | 43 (17.6%) | 46 (10.4%) | 7.18 | 1 | <.01 |

| Caregivers’ characteristics | ||||||

| Affiliation to care recipient | 10.67 | 2 | .005 | |||

| Child | 493 (71.9%) | 158 (64.8%) | 335 (75.8%) | |||

| Spouse | 120 (17.5%) | 57 (23.4%) | 63 (14.3%) | |||

| Other | 73 (10.6%) | 29 (11.9%) | 44 (10%) | |||

| Age | 60.6 (11.5) | 61.0 (12.2) | 60.4 (11.1) | −.62 | 681 | .54 |

| Age of child caregivers | 56.6 (7.76) | 55.5 (7.85) | 57.2 (7.67) | 2.32 | 489 | .02 |

| Age of spouse caregivers | 78.0 (6.3) | 77.3 (5.9) | 78.6 (6.6) | 1.13 | 118 | .26 |

| Age of other caregivers | 59.0 (12.9) | 58.8 (12.6) | 59.1 (13.3) | .09 | 70 | .93 |

| Gender | 2.63 | 1 | .12 | |||

| Woman | 469 (69.1%) | 175 (72.9%) | 294 (62.7%) | |||

| Financial status | 25.9 | 1 | <.001 | |||

| Can’t make ends meet | 141 (21.0%) | 76 (31.8%) | 65 (15.1%) | |||

| Lives with care recipients | 202 (29.7%) | 109 (44.9%) | 93 (21.2%) | 41.8 | 1 | <.001 |

| Primary appraisal | ||||||

| Assistance in ADLs/IADLs | 3.9 (3.34) | 4.7 (3.46) | 3.4 (3.17) | −4.99 | 684 | <.001 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Satisfaction with services (1–5) | 4.2 (.73) | 3.8 (.75) | 4.4 (.65) | 9.52 | 676 | <.001 |

| Secondary appraisal | ||||||

| Subjective burden (0–48) | 5.9 (9.17) | 7.7 (10.27) | 4.9 (8.34) | −3.94 | 684 | <.01 |

| Distress due to NPSY (0–5) | 2.1 (1.81) | 2.2 (1.82) | 2.0 (1.80) | −1.92 | 684 | .06 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Well-being (0–5) | 3.2 (1.14) | 3.0 (1.24) | 3.3 (1.07) | 2.83 | 678 | .005 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | 2.8 (1.07) | 2.5 (1.07) | 3.0 (.98) | 6.08 | 678 | <.001 |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The NIII does not have data concerning the characteristics of family caregivers or home care workers. Hence, based on data collected by the NIII to determine eligibility status for home care, we were able to compare the care recipients’ characteristics of those family members who participated in the study versus those who did not participate. There were no significant differences in terms of age, living arrangement (alone vs. with family), ADL impairment, or need for supervision between older care recipients of family members who participated in the study and those who did not. There were significant differences in terms of gender, with family members of older men being more likely to participate in the study (229, 33.2%) than not to participate (186, 23.0%; χ2[1] = 19.37, p < .001).

Sample Size

Our sample size of 686 family members was adequate for examining the proposed model. Our power estimations suggested that in order to obtain a significant effect of type of home care services on well-being, a sample size of 650 would provide a power of 1 to detect a possible effect of .3. In order to detect a much smaller effect of .1, a sample size of 650 would result in a power of .62.

Measures

Caregivers’ Outcomes

Subjective health status

Health status was evaluated on a 5-point scale, with a higher score representing better health. The use of a single item to assess health status is common and has shown to be a strong predictor of morbidity and mortality in past research (Ayalon & Covinsky, 2009).

Well-being

Well-being was evaluated by the World Health Organization-5 well-being index. The measure includes five items that evaluate positive mood, vitality, and general interest on a 6-point scale, with a higher score indicating better well-being. Range of the entire scale was between 0 and 5 (Heun, Bonsignore, Barkow, & Jessen, 2001). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .93.

Secondary Appraisal

Subjective burden

Sub-jective caregiving burden associated with assisting the care recipient with ADL and IADL activities was measured using 12 items. Each item was ranked on a scale ranging from 0 (no burden) to 4 (high levels of burden). Range of the entire scale was between 0 and 48, with a higher score indicating greater subjective burden (Cohen, Levin, Gagin, & Friedman, 2007). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .98.

Distress

Distress associated with the care recipient’s NPSY was assessed by asking respondents to rate their level of distress on a 0–5 scale in relation to each of the 12 NPSY. A mean score was calculated with a higher score, indicating greater distress (Cummings, 1997). Range of the total scale score mean was between 0 and 5. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .86.

Mediators

Use of home care services

Live-in versus live-out home care use was determined based on self-report.

Adult day care center

Respondents were asked whether the care recipient attended an adult day care center. Given the design of the study, this service was evaluated only as a potential addendum to home care use.

Satisfaction with the services provided by the home care worker

The Home Care Satisfaction Measure (Geron et al., 2000) was designed specifically for the assessment of home care services. The original measure consisted of 13 questions concerning satisfaction with the home health aide or homemaker. Four additional questions, such as my “my home care worker communicates easily,” deemed relevant based on qualitative interviews with the involved parties (Ayalon, 2009, 2011) and were added in the present study. The revised measure consisted of 17 items, ranging on a 0–10 scale. A mean score was calculated, with a higher score indicating greater satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .90.

Primary Appraisal

Informal care

Whether the family member provided assistance to the care recipient in ADLs and IADLs was assessed on a 12-item scale. Range of the entire scale was between 0 and 12, with a higher score indicating greater assistance (Cohen et al., 2007). Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Primary Stressors

Functional status

Functional status was evaluated in terms of the care recipient’s ability to perform six ADLs (e.g., eating, dressing; Katz, Downs, Cash, & Grotz, 1970) and six IADLs (e.g., preparing a meal, managing finances; Lawton & Brody, 1969). The sum of impaired activities was calculated to reflect overall impairment in ADLs or IADLs. Range was between 0 and 12, with a higher score indicating greater impairment. Cronbach’s alpha was .82.

Neuropsychiatric symptom inventory

The measure was developed to assess NPSY in a variety of neurologic disorders. The inventory includes 12 items: 10 behavioral and 2 neurodegenerative items. Respondents were asked to indicate whether a symptom was present (Cummings, 1997). A summary of all symptoms present was calculated, producing a range of 0–12. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .81.

Supervision needs

This crude score is determined by social workers or nurses following a semistructured interview with the older adult and his or her family members in order to determine home care eligibility. A score of 0 represents no need for supervision, whereas a score of 9 represents a need for the maximum level of supervision.

Sociodemographic Variables

Caregivers’ characteristics

Age, gender, financial status (cannot make ends meet vs. enough, comfortable, or excellent), living arrangement (with or without the care recipient), and relationship to the care recipient (child, spouse, or other) were gathered based on self-report.

Care recipients’ characteristics

Age and gender were based on either the caregiver’s or the care recipient’s self-report. Age was subsequently verified against the records of the NIII.

Analysis

We first ran descriptive statistics. To compare live-in with live-out home care settings, we conducted t tests for continuous variables and chi-squares for categorical variables. A correlational matrix of all potential variables in the proposed model was also obtained. Next, we conducted path analysis to examine the theoretical model. Mplus version 6.11 was used (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011). The advantage of using a path analysis over a conventional regression analysis is that the fit indices of the entire model are provided, rather than fit indices for each path separately. We report the following goodness of fit statistics: chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error (RMSEA; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Raykov, Tomer, & Nesselroade, 1991). If the chi-square is small relative to the degrees of freedom, resulting in a ratio between two and five, then the observed data do not differ significantly from the hypothesized model (Kelm, 2000). In addition, CFI more than .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1995) and RMSEA less than .08 (Musil, Jones, & Warner, 1998) are indicative of acceptable model fit. The significant level criterion for all statistical tests was set at .05.

Our conceptual model suggests direct paths from the primary stressors to informal assistance with ADL/IADL, type of home care services and adult day care use as well as direct paths to the caregiver’s satisfaction with services, the caregiver’s subjective burden and distress and the caregiver’s well-being and subjective health status; direct paths from informal assistance with ADL/IADL, type of home care and adult day care use to satisfaction with services, subjective burden, distress, and the caregiver’s well-being and subjective health status; direct paths from satisfaction with services to subjective burden, distress, and the caregiver’s well-being and subjective health status; and direct paths from subjective burden and distress to the caregiver’s well-being and subjective health status. Demographic characteristics were included as potential covariates. Primary stressors were allowed to correlate as well as caregivers outcomes. Formal and informal care were also allowed to correlate.

As part of the model, we examined satisfaction with home care services as a potential mediator of the relationship between home care type, secondary appraisal, and caregivers’ outcomes. For the mediational model, we used a bootstrapping procedure to obtain estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) around the indirect effects. We used a bootstrap threshold of 5,000. This approach obtains more precise estimates and can assess indirect effects of multiple mediators (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010). Mplus does not provide fit indices when a bootstrapping is used. Hence, the fit indices were obtained prior to bootstrapping.

Results

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the sample. A total of 686 caregivers participated in the study. Of these, 244 had a live-out and 422 had a live-in caregiving arrangement. There were no differences in terms of age between caregivers who relied on live-out home care versus those who relied on live-in home care, with the exception of older children being more likely to rely on live-in home care. Spouse caregivers were more likely to use live-out home care services, whereas child caregivers tended to rely on live-in home care services. Caregivers who relied on live-out home care services were more likely to describe their financial status as poor and were more likely to live with the care recipients. They tended to provide more informal caregiving assistance and to report higher levels of burden associated with the provision of ADL and IADL assistance. Caregivers who relied on live-out home care services tended to report lower levels of well-being and poorer subjective health status compared with those who relied on live-in care. They also reported lower levels of satisfaction with home care services. Care recipients under the live-out home care arrangement were younger, had lower levels of ADL and IADL impairment, but higher levels of NPSY relative to those who relied on live-in home care services. Care recipients under live-out home care services were also more likely to use adult day care centers.

Table 2 summarizes the correlation matrix of all variables in the conceptual model.

A Correlation Matrix of All Variables in the Conceptual Model

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 18 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child (reference group) versus spouse | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child (reference group) versus other | −.16** | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. CG age | .70** | −.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. CG woman (reference group) | .04 | −.03 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.05 | .01 | .03 | .08* | ||||||||||||||

| 6. CG lives with CR (reference group) | −.69*** | .12** | −.44*** | −.004 | .21*** | |||||||||||||

| 7. Assistance with ADL/IADL | .15*** | −.10** | .04 | −.07 | −.17*** | −.34*** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Subjective burden | .19*** | −.10* | .11** | −.12** | −.19*** | −.21*** | .65*** | |||||||||||

| 9. NPSY distress | −.10* | .04 | −.10* | −.05 | −.19*** | .06 | .31*** | .27*** | ||||||||||

| 10. Well-being | −.31*** | .06 | −.22*** | .11** | .23*** | .31** | −.24*** | −.35*** | −.20*** | |||||||||

| 11. Subjective health | −.43*** | −.04 | −.46*** | .08* | .18*** | .43** | −.16*** | −.17*** | −.08* | .40*** | ||||||||

| 12. Service satisfaction | .02 | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | −.001 | .002 | −.10* | −.14** | −.10** | .13** | .07 | |||||||

| 13. CR ADL/IADL impairment | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | −.002 | −.01 | .31*** | .26*** | .13** | −.04 | .04 | .26*** | ||||||

| 14. CR NPSY | −.12** | .02 | −.12** | −.03 | −.17*** | .04 | .35*** | .29*** | .63*** | −.24*** | −.08* | −.10** | .11** | |||||

| 15. CR supervision needs | .10** | −.04 | .05 | .01 | .01 | −.13** | .09* | .06 | .04 | −.07 | −.02 | .03 | .14*** | .10* | ||||

| 16. CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | −.003 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .06 | .14*** | −.03 | −.11** | |||

| 17. CR age | −.26*** | −.02 | .10* | −.02 | .13** | .19*** | −.07 | −.11* | −.03 | .08* | .09* | .09* | .09* | −.03 | −.10** | .08 | ||

| 18. CR woman (reference group) | .30*** | .003 | .08* | −.16*** | −.04 | −.19*** | −.004 | .03 | −.04 | −.12** | −.11** | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .03 | .04 | −.01 | |

| 19. Live-out (reference group) versus live-in | −.12** | −.03 | −.02 | .06 | .20*** | .25*** | −.19*** | −.14*** | −.07 | .11** | .23** | .34*** | .41*** | −.10* | −.01 | .10** | .20** | −.03 |

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 18 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child (reference group) versus spouse | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child (reference group) versus other | −.16** | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. CG age | .70** | −.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. CG woman (reference group) | .04 | −.03 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.05 | .01 | .03 | .08* | ||||||||||||||

| 6. CG lives with CR (reference group) | −.69*** | .12** | −.44*** | −.004 | .21*** | |||||||||||||

| 7. Assistance with ADL/IADL | .15*** | −.10** | .04 | −.07 | −.17*** | −.34*** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Subjective burden | .19*** | −.10* | .11** | −.12** | −.19*** | −.21*** | .65*** | |||||||||||

| 9. NPSY distress | −.10* | .04 | −.10* | −.05 | −.19*** | .06 | .31*** | .27*** | ||||||||||

| 10. Well-being | −.31*** | .06 | −.22*** | .11** | .23*** | .31** | −.24*** | −.35*** | −.20*** | |||||||||

| 11. Subjective health | −.43*** | −.04 | −.46*** | .08* | .18*** | .43** | −.16*** | −.17*** | −.08* | .40*** | ||||||||

| 12. Service satisfaction | .02 | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | −.001 | .002 | −.10* | −.14** | −.10** | .13** | .07 | |||||||

| 13. CR ADL/IADL impairment | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | −.002 | −.01 | .31*** | .26*** | .13** | −.04 | .04 | .26*** | ||||||

| 14. CR NPSY | −.12** | .02 | −.12** | −.03 | −.17*** | .04 | .35*** | .29*** | .63*** | −.24*** | −.08* | −.10** | .11** | |||||

| 15. CR supervision needs | .10** | −.04 | .05 | .01 | .01 | −.13** | .09* | .06 | .04 | −.07 | −.02 | .03 | .14*** | .10* | ||||

| 16. CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | −.003 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .06 | .14*** | −.03 | −.11** | |||

| 17. CR age | −.26*** | −.02 | .10* | −.02 | .13** | .19*** | −.07 | −.11* | −.03 | .08* | .09* | .09* | .09* | −.03 | −.10** | .08 | ||

| 18. CR woman (reference group) | .30*** | .003 | .08* | −.16*** | −.04 | −.19*** | −.004 | .03 | −.04 | −.12** | −.11** | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .03 | .04 | −.01 | |

| 19. Live-out (reference group) versus live-in | −.12** | −.03 | −.02 | .06 | .20*** | .25*** | −.19*** | −.14*** | −.07 | .11** | .23** | .34*** | .41*** | −.10* | −.01 | .10** | .20** | −.03 |

Notes: CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

A Correlation Matrix of All Variables in the Conceptual Model

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 18 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child (reference group) versus spouse | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child (reference group) versus other | −.16** | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. CG age | .70** | −.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. CG woman (reference group) | .04 | −.03 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.05 | .01 | .03 | .08* | ||||||||||||||

| 6. CG lives with CR (reference group) | −.69*** | .12** | −.44*** | −.004 | .21*** | |||||||||||||

| 7. Assistance with ADL/IADL | .15*** | −.10** | .04 | −.07 | −.17*** | −.34*** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Subjective burden | .19*** | −.10* | .11** | −.12** | −.19*** | −.21*** | .65*** | |||||||||||

| 9. NPSY distress | −.10* | .04 | −.10* | −.05 | −.19*** | .06 | .31*** | .27*** | ||||||||||

| 10. Well-being | −.31*** | .06 | −.22*** | .11** | .23*** | .31** | −.24*** | −.35*** | −.20*** | |||||||||

| 11. Subjective health | −.43*** | −.04 | −.46*** | .08* | .18*** | .43** | −.16*** | −.17*** | −.08* | .40*** | ||||||||

| 12. Service satisfaction | .02 | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | −.001 | .002 | −.10* | −.14** | −.10** | .13** | .07 | |||||||

| 13. CR ADL/IADL impairment | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | −.002 | −.01 | .31*** | .26*** | .13** | −.04 | .04 | .26*** | ||||||

| 14. CR NPSY | −.12** | .02 | −.12** | −.03 | −.17*** | .04 | .35*** | .29*** | .63*** | −.24*** | −.08* | −.10** | .11** | |||||

| 15. CR supervision needs | .10** | −.04 | .05 | .01 | .01 | −.13** | .09* | .06 | .04 | −.07 | −.02 | .03 | .14*** | .10* | ||||

| 16. CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | −.003 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .06 | .14*** | −.03 | −.11** | |||

| 17. CR age | −.26*** | −.02 | .10* | −.02 | .13** | .19*** | −.07 | −.11* | −.03 | .08* | .09* | .09* | .09* | −.03 | −.10** | .08 | ||

| 18. CR woman (reference group) | .30*** | .003 | .08* | −.16*** | −.04 | −.19*** | −.004 | .03 | −.04 | −.12** | −.11** | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .03 | .04 | −.01 | |

| 19. Live-out (reference group) versus live-in | −.12** | −.03 | −.02 | .06 | .20*** | .25*** | −.19*** | −.14*** | −.07 | .11** | .23** | .34*** | .41*** | −.10* | −.01 | .10** | .20** | −.03 |

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 18 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child (reference group) versus spouse | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child (reference group) versus other | −.16** | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. CG age | .70** | −.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. CG woman (reference group) | .04 | −.03 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.05 | .01 | .03 | .08* | ||||||||||||||

| 6. CG lives with CR (reference group) | −.69*** | .12** | −.44*** | −.004 | .21*** | |||||||||||||

| 7. Assistance with ADL/IADL | .15*** | −.10** | .04 | −.07 | −.17*** | −.34*** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Subjective burden | .19*** | −.10* | .11** | −.12** | −.19*** | −.21*** | .65*** | |||||||||||

| 9. NPSY distress | −.10* | .04 | −.10* | −.05 | −.19*** | .06 | .31*** | .27*** | ||||||||||

| 10. Well-being | −.31*** | .06 | −.22*** | .11** | .23*** | .31** | −.24*** | −.35*** | −.20*** | |||||||||

| 11. Subjective health | −.43*** | −.04 | −.46*** | .08* | .18*** | .43** | −.16*** | −.17*** | −.08* | .40*** | ||||||||

| 12. Service satisfaction | .02 | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | −.001 | .002 | −.10* | −.14** | −.10** | .13** | .07 | |||||||

| 13. CR ADL/IADL impairment | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | −.002 | −.01 | .31*** | .26*** | .13** | −.04 | .04 | .26*** | ||||||

| 14. CR NPSY | −.12** | .02 | −.12** | −.03 | −.17*** | .04 | .35*** | .29*** | .63*** | −.24*** | −.08* | −.10** | .11** | |||||

| 15. CR supervision needs | .10** | −.04 | .05 | .01 | .01 | −.13** | .09* | .06 | .04 | −.07 | −.02 | .03 | .14*** | .10* | ||||

| 16. CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | −.003 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .06 | .14*** | −.03 | −.11** | |||

| 17. CR age | −.26*** | −.02 | .10* | −.02 | .13** | .19*** | −.07 | −.11* | −.03 | .08* | .09* | .09* | .09* | −.03 | −.10** | .08 | ||

| 18. CR woman (reference group) | .30*** | .003 | .08* | −.16*** | −.04 | −.19*** | −.004 | .03 | −.04 | −.12** | −.11** | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .03 | .04 | −.01 | |

| 19. Live-out (reference group) versus live-in | −.12** | −.03 | −.02 | .06 | .20*** | .25*** | −.19*** | −.14*** | −.07 | .11** | .23** | .34*** | .41*** | −.10* | −.01 | .10** | .20** | −.03 |

Notes: CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Type of home care was associated with relationship to the care recipient, the caregiver’s financial status and living arrangements, the care recipient’s age, ADL/IADL impairment and NPSY, the care recipient’s attendance of an adult day care center and the caregiver’s well-being, subjective health status, service satisfaction, assistance with ADL/IADL, and burden.

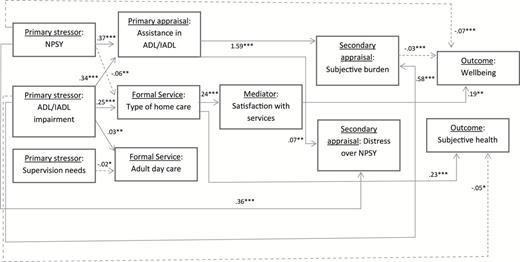

We excluded 50 cases from the path analysis due to missing values. The conceptual model had an adequate fit: χ2 (df) = 36.38 (25), RMSEA (CI) = .03 (.00–.05), CFI = .99. Table 3 outlines the results and Figure 1 provides a graphical summary of the significant paths. A consistent sociodemographic variable that had direct paths to several of the variables in the model was the caregiver’s financial status. Those of lower financial status were more likely to employ a live-out home care worker. They were also more likely to report higher levels of satisfaction with services, higher levels of subjective burden, higher levels of distress associated with NPSY, lower well-being and lower subjective health.

Path Analysis of the Conceptual Model

| . | Informal assistance with ADL/IADL . | Live-in versus Live-out home care . | Use of adult day care center . | Satisfaction with services . | Subjective burden . | NPSY distress . | Subjective health . | Well-being . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG age | −.03 (.02) | −.004 (.009) | −.003 (.003) | −.003 (.004) | .04 (.06) | −.003 (.01) | −.03*** (.006) | −.002 (.006) |

| CG gender (woman reference group) | −.40 (.29) | .15 (.14) | .02 (.03) | −.06 (.06) | −1.55 (.84) | −.10 (.16) | .12 (.08) | .14 (.10) |

| CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.57 (.31) | .50** (.15) | −.04 (.04) | −.16** (.08) | −2.37** (.81) | −.73*** (.19) | .21* (.09) | .46*** (.10) |

| CG child versus spouse | −.89 (.68) | .58 (.34) | .03 (.08) | .06 (.16) | 4.68* (2.09) | −.14 (.40) | −.19 (.23) | −.40* (.19) |

| CG child versus other | −.79 (.53) | −.16 (.22) | .001 (.05) | .0 8(.09) | −1.67 (1.94) | .17 (.25) | −.27*(.14) | .04 (.13) |

| CG live with CR (reference group) | −3.14*** (.38) | .93*** (.18) | −.01 (.05) | −.22* (.10) | 3.98** (1.21) | .50* (.24) | .49***(.13) | .47*** (.13) |

| CR age | .005 (.02) | .05*** (.01) | .005 (.003) | .001 (.005) | −.04 (.07) | .001 (.01) | −.007 (.008) | −.004 (.007) |

| CR gender (woman reference group) | −.42 (.31) | −.007 (.15) | .02 (.04) | −.06 (.06) | −.19 (1.01) | −.08 (.17) | −.02 (.09) | −.04 (.10) |

| ADL/IADL impairment | .34*** (.05) | .25*** (.02) | .03** (.01) | .01 (.01) | .58* (.28) | .04 (.03) | −.05* (.02) | .02 (.02) |

| NPSY | .37*** (.04) | −.06** (.02) | −.006 (.005) | −.01 (.01) | .20 (.12) | .36*** (.03) | −.04 (.02) | −.07*** (.02) |

| Supervision needs | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.02) | −.02* (.007) | .004 (.007) | −.09 (.11) | −.004 (.02) | .02 (.01) | −.006 (.01) |

| Informal assistance with ADL/IADL | −.02 (.01) | 1.59*** (.12) | .07** (.02) | .03 (.02) | .03 (.01) | |||

| Type of home care (live- out reference group) | .24***(.03) | −.47 (.56) | −.06 (.09) | .23*** (.06) | −.09 (.07) | |||

| CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | .02(.08) | −.59 (.96) | −.05 (.16) | .16 (.12) | .02 (.11) | |||

| Satisfaction with services | −.80 (.54) | −.05 (.09) | −.03 (.05) | .19** (.07) | ||||

| Subjective burden | −.004 (.006) | −.03*** (.005) | ||||||

| NPSY distress | .01 (.03) | −.05 (.03) | ||||||

| R2 | .35 | .42 | .07 | .21 | .46 | .43 | .35 | .27 |

| . | Informal assistance with ADL/IADL . | Live-in versus Live-out home care . | Use of adult day care center . | Satisfaction with services . | Subjective burden . | NPSY distress . | Subjective health . | Well-being . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG age | −.03 (.02) | −.004 (.009) | −.003 (.003) | −.003 (.004) | .04 (.06) | −.003 (.01) | −.03*** (.006) | −.002 (.006) |

| CG gender (woman reference group) | −.40 (.29) | .15 (.14) | .02 (.03) | −.06 (.06) | −1.55 (.84) | −.10 (.16) | .12 (.08) | .14 (.10) |

| CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.57 (.31) | .50** (.15) | −.04 (.04) | −.16** (.08) | −2.37** (.81) | −.73*** (.19) | .21* (.09) | .46*** (.10) |

| CG child versus spouse | −.89 (.68) | .58 (.34) | .03 (.08) | .06 (.16) | 4.68* (2.09) | −.14 (.40) | −.19 (.23) | −.40* (.19) |

| CG child versus other | −.79 (.53) | −.16 (.22) | .001 (.05) | .0 8(.09) | −1.67 (1.94) | .17 (.25) | −.27*(.14) | .04 (.13) |

| CG live with CR (reference group) | −3.14*** (.38) | .93*** (.18) | −.01 (.05) | −.22* (.10) | 3.98** (1.21) | .50* (.24) | .49***(.13) | .47*** (.13) |

| CR age | .005 (.02) | .05*** (.01) | .005 (.003) | .001 (.005) | −.04 (.07) | .001 (.01) | −.007 (.008) | −.004 (.007) |

| CR gender (woman reference group) | −.42 (.31) | −.007 (.15) | .02 (.04) | −.06 (.06) | −.19 (1.01) | −.08 (.17) | −.02 (.09) | −.04 (.10) |

| ADL/IADL impairment | .34*** (.05) | .25*** (.02) | .03** (.01) | .01 (.01) | .58* (.28) | .04 (.03) | −.05* (.02) | .02 (.02) |

| NPSY | .37*** (.04) | −.06** (.02) | −.006 (.005) | −.01 (.01) | .20 (.12) | .36*** (.03) | −.04 (.02) | −.07*** (.02) |

| Supervision needs | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.02) | −.02* (.007) | .004 (.007) | −.09 (.11) | −.004 (.02) | .02 (.01) | −.006 (.01) |

| Informal assistance with ADL/IADL | −.02 (.01) | 1.59*** (.12) | .07** (.02) | .03 (.02) | .03 (.01) | |||

| Type of home care (live- out reference group) | .24***(.03) | −.47 (.56) | −.06 (.09) | .23*** (.06) | −.09 (.07) | |||

| CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | .02(.08) | −.59 (.96) | −.05 (.16) | .16 (.12) | .02 (.11) | |||

| Satisfaction with services | −.80 (.54) | −.05 (.09) | −.03 (.05) | .19** (.07) | ||||

| Subjective burden | −.004 (.006) | −.03*** (.005) | ||||||

| NPSY distress | .01 (.03) | −.05 (.03) | ||||||

| R2 | .35 | .42 | .07 | .21 | .46 | .43 | .35 | .27 |

Notes: Estimates and standard errors are reported. ADL/IADL impairment, NPSY and need for supervision were allowed to correlate (not reported here). Informal assistance with ADL/IADL and type of home care were allowed to correlate (not reported here). A significant indirect path from type of home care to well-being via satisfaction with services was found: estimate (95% confidence interval) = .05**(.02–.09). CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Path Analysis of the Conceptual Model

| . | Informal assistance with ADL/IADL . | Live-in versus Live-out home care . | Use of adult day care center . | Satisfaction with services . | Subjective burden . | NPSY distress . | Subjective health . | Well-being . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG age | −.03 (.02) | −.004 (.009) | −.003 (.003) | −.003 (.004) | .04 (.06) | −.003 (.01) | −.03*** (.006) | −.002 (.006) |

| CG gender (woman reference group) | −.40 (.29) | .15 (.14) | .02 (.03) | −.06 (.06) | −1.55 (.84) | −.10 (.16) | .12 (.08) | .14 (.10) |

| CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.57 (.31) | .50** (.15) | −.04 (.04) | −.16** (.08) | −2.37** (.81) | −.73*** (.19) | .21* (.09) | .46*** (.10) |

| CG child versus spouse | −.89 (.68) | .58 (.34) | .03 (.08) | .06 (.16) | 4.68* (2.09) | −.14 (.40) | −.19 (.23) | −.40* (.19) |

| CG child versus other | −.79 (.53) | −.16 (.22) | .001 (.05) | .0 8(.09) | −1.67 (1.94) | .17 (.25) | −.27*(.14) | .04 (.13) |

| CG live with CR (reference group) | −3.14*** (.38) | .93*** (.18) | −.01 (.05) | −.22* (.10) | 3.98** (1.21) | .50* (.24) | .49***(.13) | .47*** (.13) |

| CR age | .005 (.02) | .05*** (.01) | .005 (.003) | .001 (.005) | −.04 (.07) | .001 (.01) | −.007 (.008) | −.004 (.007) |

| CR gender (woman reference group) | −.42 (.31) | −.007 (.15) | .02 (.04) | −.06 (.06) | −.19 (1.01) | −.08 (.17) | −.02 (.09) | −.04 (.10) |

| ADL/IADL impairment | .34*** (.05) | .25*** (.02) | .03** (.01) | .01 (.01) | .58* (.28) | .04 (.03) | −.05* (.02) | .02 (.02) |

| NPSY | .37*** (.04) | −.06** (.02) | −.006 (.005) | −.01 (.01) | .20 (.12) | .36*** (.03) | −.04 (.02) | −.07*** (.02) |

| Supervision needs | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.02) | −.02* (.007) | .004 (.007) | −.09 (.11) | −.004 (.02) | .02 (.01) | −.006 (.01) |

| Informal assistance with ADL/IADL | −.02 (.01) | 1.59*** (.12) | .07** (.02) | .03 (.02) | .03 (.01) | |||

| Type of home care (live- out reference group) | .24***(.03) | −.47 (.56) | −.06 (.09) | .23*** (.06) | −.09 (.07) | |||

| CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | .02(.08) | −.59 (.96) | −.05 (.16) | .16 (.12) | .02 (.11) | |||

| Satisfaction with services | −.80 (.54) | −.05 (.09) | −.03 (.05) | .19** (.07) | ||||

| Subjective burden | −.004 (.006) | −.03*** (.005) | ||||||

| NPSY distress | .01 (.03) | −.05 (.03) | ||||||

| R2 | .35 | .42 | .07 | .21 | .46 | .43 | .35 | .27 |

| . | Informal assistance with ADL/IADL . | Live-in versus Live-out home care . | Use of adult day care center . | Satisfaction with services . | Subjective burden . | NPSY distress . | Subjective health . | Well-being . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG age | −.03 (.02) | −.004 (.009) | −.003 (.003) | −.003 (.004) | .04 (.06) | −.003 (.01) | −.03*** (.006) | −.002 (.006) |

| CG gender (woman reference group) | −.40 (.29) | .15 (.14) | .02 (.03) | −.06 (.06) | −1.55 (.84) | −.10 (.16) | .12 (.08) | .14 (.10) |

| CG financial status (cannot make ends meet reference group) | −.57 (.31) | .50** (.15) | −.04 (.04) | −.16** (.08) | −2.37** (.81) | −.73*** (.19) | .21* (.09) | .46*** (.10) |

| CG child versus spouse | −.89 (.68) | .58 (.34) | .03 (.08) | .06 (.16) | 4.68* (2.09) | −.14 (.40) | −.19 (.23) | −.40* (.19) |

| CG child versus other | −.79 (.53) | −.16 (.22) | .001 (.05) | .0 8(.09) | −1.67 (1.94) | .17 (.25) | −.27*(.14) | .04 (.13) |

| CG live with CR (reference group) | −3.14*** (.38) | .93*** (.18) | −.01 (.05) | −.22* (.10) | 3.98** (1.21) | .50* (.24) | .49***(.13) | .47*** (.13) |

| CR age | .005 (.02) | .05*** (.01) | .005 (.003) | .001 (.005) | −.04 (.07) | .001 (.01) | −.007 (.008) | −.004 (.007) |

| CR gender (woman reference group) | −.42 (.31) | −.007 (.15) | .02 (.04) | −.06 (.06) | −.19 (1.01) | −.08 (.17) | −.02 (.09) | −.04 (.10) |

| ADL/IADL impairment | .34*** (.05) | .25*** (.02) | .03** (.01) | .01 (.01) | .58* (.28) | .04 (.03) | −.05* (.02) | .02 (.02) |

| NPSY | .37*** (.04) | −.06** (.02) | −.006 (.005) | −.01 (.01) | .20 (.12) | .36*** (.03) | −.04 (.02) | −.07*** (.02) |

| Supervision needs | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.02) | −.02* (.007) | .004 (.007) | −.09 (.11) | −.004 (.02) | .02 (.01) | −.006 (.01) |

| Informal assistance with ADL/IADL | −.02 (.01) | 1.59*** (.12) | .07** (.02) | .03 (.02) | .03 (.01) | |||

| Type of home care (live- out reference group) | .24***(.03) | −.47 (.56) | −.06 (.09) | .23*** (.06) | −.09 (.07) | |||

| CR attends adult day care center (reference group) | .02(.08) | −.59 (.96) | −.05 (.16) | .16 (.12) | .02 (.11) | |||

| Satisfaction with services | −.80 (.54) | −.05 (.09) | −.03 (.05) | .19** (.07) | ||||

| Subjective burden | −.004 (.006) | −.03*** (.005) | ||||||

| NPSY distress | .01 (.03) | −.05 (.03) | ||||||

| R2 | .35 | .42 | .07 | .21 | .46 | .43 | .35 | .27 |

Notes: Estimates and standard errors are reported. ADL/IADL impairment, NPSY and need for supervision were allowed to correlate (not reported here). Informal assistance with ADL/IADL and type of home care were allowed to correlate (not reported here). A significant indirect path from type of home care to well-being via satisfaction with services was found: estimate (95% confidence interval) = .05**(.02–.09). CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY = neuropsychiatric symptoms.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Path model. Background variables were included in the model but are not presented because these are not central to the model. Only significant estimates are included. Dashed line indicates negative relationship. A significant indirect path from type of home care to well-being via satisfaction with services: estimate (confidence interval) = .04*(.01–.09). *p < .05. **p < 01. ***p < .001. ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; NPSY, neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Another consistent predictor was living arrangement. Living with the care recipient was associated with lower levels of well-being, subjective health, burden and distress over NPSY, higher levels of satisfaction with home care, a lower likelihood of relying on live-in home care and a greater likelihood of providing informal assistance with ADL/IADL.

Younger caregivers reported better subjective health. Spouse caregivers reported higher levels of subjective burden and lower levels of well-being compared with children as caregivers. Those caregivers identified as “other” reported worse subjective health than children as caregivers. Older care recipients were more likely to rely on live-in home care.

There were positive paths from ADL/IADL impairment to informal assistance with ADL/IADL and type of home care services, so that greater impairment was associated with more informal assistance and a greater likelihood of relying on live-in home care services. Greater ADL/IADL impairment was associated with a lower likelihood of attending an adult day care center. Greater ADL/IADL impairment of the care recipient was also associated with higher levels of the caregiver’s subjective burden and lower levels of subjective health. There was a positive path from NPSY to informal assistance with ADL/IADL and a negative path to type of home care, suggesting that higher levels of NPSY among the care recipient were associated with higher levels of ADL/IADL assistance and a reduced likelihood of having a live-in home care worker. There were also direct paths from NPSY to distress over NPSY and well-being, with higher levels of NPSY being associated with higher distress over NPSY and lower well-being. A direct path from need for supervision to adult day care center use suggested that those in need for supervision were more likely to attend adult day care centers. Informal assistance with ADL/IADL had a direct path to subjective burden and distress over NPSY, with more informal assistance being associated with higher subjective burden and distress over NPSY. Type of home care had direct paths to satisfaction with services and subjective health, with live-in home care being associated with higher levels of satisfaction with services and higher subjective health. Type of home care also had an indirect path to well-being via satisfaction with services: estimate (95% CI) = .05**(.02–.09), p < .01. Satisfaction with services had a direct path to well-being, with higher levels of satisfaction being associated with higher levels of well-being. Finally, subjective burden had a direct path to well-being, with higher subjective burden being associated with lower levels of well-being.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the role of type of home care services and satisfaction with these services in the caregiver’s burden, distress, well-being, and subjective health status within the conceptual model proposed by Yates and coworkers (1999). Our findings demonstrate that both type of home care services and satisfaction with services play a major role in caregivers’ outcomes. The present findings are important as they provide a preliminary evaluation of two types of home care services, which are aimed to assist older adults to remain in their home environment for as long as they possibly can.

A notable finding is the significant relationship between type of home care services and the caregiver’s satisfaction with these services. Consistent with past research that found higher levels of satisfaction among live-in home care recipients (Iecovich, 2007), we found that those caregivers whose care recipient relied on live-in home care reported higher levels of satisfaction with services. This finding is important given the reliance on home care services in many developing countries (Onder et al., 2007), and in light of current efforts to reduce the availability of live-in migrant home care services in Israel (Asiskovitch, 2013; Natan, 2011), by providing additional subsidy for live-out home care services (Natan, 2011) and by actively restricting the number of new migrant home care workers in the country (Natan, 2012). This is further supported by the fact that most families and older adults that currently rely on migrant home care do not wish to switch to an Israeli worker even at the hypothetical addition of 50hr of subsidiary care per week (Ayalon, Green, Eliav, Asiskovitch, & Shmeltzer, 2013).

Although the caregiver’s satisfaction with services provided to the care recipient is important in its own right, as a means to empower clients and fulfill their wishes, satisfaction with services is also important because of its association with the caregiver’s outcomes. Our findings demonstrate that higher levels of satisfaction with services are directly related to higher levels of well-being. Hence, the findings provide preliminary empirical support to the potential importance of satisfaction with services.

Interestingly, type of home care services had both a direct and an indirect association with caregivers’ outcomes. Our findings indicate that live-in home care was directly associated with higher levels of subjective health and indirectly associated with better well-being, via satisfaction with services. This is despite the fact that care recipients under the live-in home care setting demonstrated higher levels of functional impairment. Therefore, the findings potentially stress the efficacy of live-in home care services.

A nonsignificant finding that should be noted is a lack of association between use of adult day care centers and caregivers’ outcomes. This is consistent with past research that found no significant effect of adult day care center use on the caregiver’s burden (Baumgarten, Lebel, Laprise, Leclerc, & Quinn, 2002) and a negative effect on risk for institutionalization (McCann et al., 2005). Because eligibility requirements for this study were such that the care recipient had to rely on home care services as our purpose was to compare the two types of home care services, we were only able to examine the role of adult day care center use as an addendum to home care services and not as a sole service. Future research will benefit from assessing the role of adult day care centers in comparison to home care services.

In the present study, we evaluated the caregiver’s secondary appraisal using two different constructs. The first represents the caregiver’s subjective burden associated with assisting the care recipient with ADL and IADL, whereas the second measure represents distress over NPSY. Higher levels of subjective burden were associated with greater ADL/IADL impairment and with more informal assistance with ADL/IADL; whereas distress over NPSY was associated with more NPSY as well as with more informal assistance with ADL/IADL. Only subjective burden associated with ADL/IADL assistance was associated with the caregiver’s well-being. Our findings demonstrate that the two constructs are somewhat different from one another. This finding is notable given past research that has linked NPSY with many negative outcomes, including the caregiver’s distress and even the care recipient’s institutionalization (Okura et al., 2011; Pang et al., 2002). The present study suggests that when both subjective burden and distress over NPSY are taken into consideration the association of distress due to NPSY with the caregiver’s outcomes is minimal.

Need is considered a major driving force behind service use, with those at higher levels of need being more likely to use home care services (Andersen, 1995; Henton et al., 2002). Although our sample consisted of care recipients of substantial levels of impairment (as the entire sample was eligible to a live-in home care worker and thus, highly impaired), we found significant differences in levels of impairment between care recipients under live-in versus live-out home care settings. Those under live-in home care had higher levels of impairment in ADL and IADL but lower levels of NPSY. This is somewhat counterintuitive, as live-in home care provides more intensive care and, thus, we expected care recipients who have higher levels of NPSY to receive more intensive care. Several potential explanations can account for this finding. First, given the subjective nature associated with the report of NPSY (Ayalon, 2010), it is possible that a caregiver who relies on live-out home care would be more aware of the care recipient’s NPSY because he or she provides more ADL and IADL assistance and, thus, has more opportunities to view problem behaviors. It is also possible that NPSY do not represent a precipitator of service use but rather an outcome in this cross-sectional design. Hence, it is possible that under live-in home care, the care recipient presents with fewer NPSY, because he or she receives round-the-clock care by a live-in home care worker who is completely dedicated to the care recipient’s well-being.

Those in need for supervision were more likely to attend an adult day care center. However, the need for supervision variable had no associations with home care type or with caregiving outcomes in the final model. This is likely due to the fact that this is an unstandardized measure employed by the NIII to determine home care eligibility. This measure was administered prior to the cross-sectional data collection employed by this study and likely is not a good indicator of the care recipient’s current status, which tends to fluctuate. Future research will benefit from employing a more standardized measure of supervision needs.

A consistent predictor in the present study was the living arrangement of the caregiver. Those caregivers who lived in the same household with the care recipients were more likely to rely on live-out home care services. As expected, they also provided more informal assistance with ADL/IADL and reported lower levels of subjective health and well-being. This is consistent with past research that has shown that caregivers who shared a residence with their care recipients were at heightened risks for deteriorated health and mortality (Schulz & Beach, 1999) as well as for poorer well-being (Arai, Kumamoto, Mizuno, & Washio, 2013). Unexpectedly, however, net of the effects of sociodemographic variables, primary stressors, service use, and informal assistance with ADL/IADL, those who lived with their care recipients reported higher levels of satisfaction with services and lower levels of burden and distress over NPSY compared with those who did not share a residence with the care recipients. These findings are supported by past research that found that even though adult children who lived with their older parents reported more activity restrictions, they also reported less relationship strains. The authors speculated that sharing a residence also implies better relationships with the care recipients (Deimling, Bass, Townsend, & Noelker, 1989). Consistently, a more recent study reported no relationship between living arrangement and burden (Baronet, 2003). We argue that potentially, at high levels of care demands as in the present study, not sharing a residence with the care recipient puts an extra toll on the caregiver who ends up being responsible for maintaining two separate households.

Consistent with past research (D’Souza et al., 2009), the present study found that enabling factors, such as financial status, are important determinants of home care service use. This suggests that even in a country that actively supports the care of older adults in their home, the financial support provided by the government is probably insufficient, as the choice between live-in versus live-out home care as well as the consequences associated with this particular choice are largely determined by the caregiver’s financial status.

This is somewhat contrasted with a recent survey by the Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor. According to that survey, financial considerations served as pull factors for live-in home care among 17% of the sample, as the costs associated with live-in home care are substantially lower than the costs associated with institutional care or with employing several Israeli home care workers around the clock (as Israeli workers hardly ever work as live-in home care workers; Bar-Zuri, 2010). In contrast, we found that the main reason given for employing a live-out home care worker was financial (e.g., lower cost compared with live-in home care), whereas the main reason for employing a live-in home care worker was the health status of the older adult, as live-in home care was perceived as more adequate for meeting the health needs of impaired older adults (Ayalon et al., 2013).

In reviewing these findings, it is important to take into consideration the distinctions between the two types of home care workers examined in the present study. Whereas live-in home care workers are primarily migrant, live-out home care workers are primarily Israeli. There is a considerable body of literature to show that some countries, such as the Philippines actively prepare their workforce for caregiving positions by fostering values of care and compassion (Browne, Braun, & Arnsberger, 2007). Hence, it is possible that the higher levels of satisfaction reported by those caregivers who rely on live-in home care services are actually a result of the work ethics and cultural values of the home care workers rather than solely a result of the amount of home care provided. Given the fact that Israeli home care workers are largely unwilling to provide round-the-clock care (Ayalon et al., 2013), further examination of this confound is not feasible at the present time in Israel.

The heavy reliance on migrant workers for the provision of home care services is not unique to Israel but is prevalent worldwide (including the United States; e.g., Tung, 2000). In their seminal review of the state of LTC workforce, Browne and Braun (2008) identified three main factors responsible for the heavy reliance on migrant care workers in the developed world. Among these are the aging of the population, globalization, and women’s migration. The low value assigned to the care of older adults in the developed world is yet another potential reason (Ayalon, Kaniel & Rosenberg, 2008). Given the fact that these trends are not likely to change in the near future, the reliance of the developed world on cheap migrant labor for LTC services is likely to continue. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that the majority of migrant LTC workers do not wish their children to work in caregiving positions (Browne et al., 2007). In addition, as migrants stay longer in the host country, their salaries increase and so do their expectations from their work environment (Ayalon et al., 2008). Hence, it is not clear whether low-cost migrant home care services are a sustainable solution to the growing population of older adults in the developed world. Given the fact that financial considerations seem to be driving at least some of the reliance on migrant home care even in a country that partially subsidizes these services, these trends call for further examination of affordable LTC alternatives, such as adult day care centers and supportive communities.

To sum up, the present study provides preliminary insights concerning the importance of type of home care services and service satisfaction in caregivers’ outcomes. Given the cross-sectional design of this study, we cannot infer cause and effect, and results should be viewed with caution. In addition, even though we relied on a representative sample, the sample was limited to the center of Israel due to its relative small size. No national data are available regarding the overall percentage of those who are eligible for a live-in home care but opted for an alternative. We identified only one other study, conducted by the Israeli Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor concerning these issues. That study found that about 10% of all live-in eligible care recipients who had asked for a license to hire a migrant home care worker opted for an alternative (Bar-Zuri, 2010). Because our population was defined differently, with a focus on eligibility rather than on actual licensure requests, the two samples are not comparable. In addition, because the NIII does not have systematic data on family caregivers or home care workers, it is unclear whether our sample is representative of these groups. Another limitation of this study stems from the fact that some of the measures demonstrated only moderate levels of internal consistency. Future research will benefit from identifying alternative measures of better reliability. Finally, whereas much attention has been given to satisfaction with the caregiving role as an important determinant of the family member’s quality of life and well-being (Martire, Stephens, & Atienza, 1997; Walker, Shin, & Bird, 1990), the present study examined only satisfaction with formal services and failed to examine satisfaction with informal caregiving.

Nonetheless, the findings suggest a potential distinction between the two types of home care services evaluated in this study, not only in relation to the caregiver’s satisfaction with services but also in relation to subjective health and well-being. The present study emphasizes the potential benefits of live-in home care services for caregivers of older adults who suffer from high levels of impairment. The study also emphasizes the important role of satisfaction with services.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mrs. Tami Eliav, Dr. Daniel Gotlieb, Dr. Sharon Asiskovitz, Mrs. Miriam Shmelzer, Mr. Alex Galia, Mr. Shaul Nimrodi, Mrs. Orel Abutbul, and Mrs. Refaela Cohen for their assistance with this project.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD