-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Judith Green, Action–research in context: revisiting the 1970s Benwell Community Development Project, Community Development Journal, Volume 52, Issue 2, April 2017, Pages 269–289, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsx003

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article examines the action–research undertaken by Benwell Community Development Project in West Newcastle in the 1970s. Taking a triangulated participant observation approach, it starts by providing an overview of how research perspectives shaped the organization of community action, before examining this in areas such as housing, employment, and welfare rights and legal services. It situates this within the historical and political context of the time, and available action–research technologies. It concludes by examining the continuing relevance of the approach taken to community development practice today.

Introduction

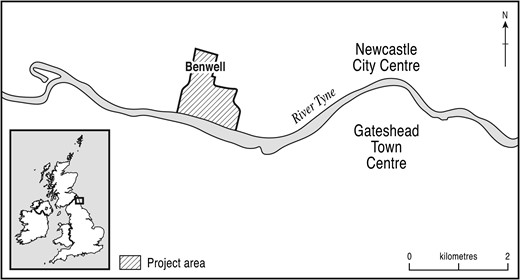

This article revisits the story of Benwell Community Development Project (CDP), based in the west end of Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, in the 1970s, one of twelve experimental projects established by national government. Whereas previous accounts of CDPs have broadly considered the programme's origins, policy context and distinctive action–research perspective (e.g. Loney, 1983; Green, 1992; Popple, 2011), this article focuses on the actual practice, including research and dissemination, of one of the local projects. This is in a sense a participant observation account, since I was a member of the Benwell CDP research team from 1974 to 1979. But it could more accurately be described as ‘triangulated reminiscence’ by which my memory of events and ideas from forty years ago has been systematically checked against other sources including documentary records, reports and publications, discussions and interviews.

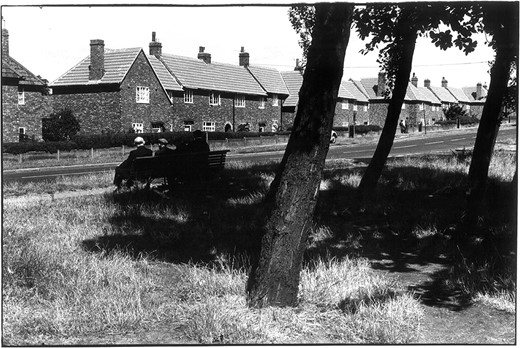

Benwell CDP, a second wave project, started in 1972. North Tyneside CDP followed close behind Benwell, the two projects located less than ten miles apart at opposite ends of the Tyneside conurbation. They shared similar perspectives on many issues, collaborating on specific projects as well as being major contributors to the inter-project reports produced by the ‘radical’ group of CDPs. Benwell as an urban area was the creation of the second phase of the Industrial Revolution. During the CDP period, it was predominantly a ‘respectable’ working class area (Davies, 1972) largely dependent on traditional industries. It was still common to meet families where three generations worked at the huge Vickers engineering factories that dominated the banks of the Tyne. Although the last coal mine had closed in the 1930s, the shafts of disused mines were still visible and there were working coal miners living in the area. However, Benwell in the 1970s was undergoing a major physical, economic and social transformation. Forty years later, it has become, like many other areas in the UK, almost completely de-industrialized. Successive ‘regeneration’ programmes have replaced or completely cleared much of the older housing, while demographic changes have altered the character of what was in the 1970s an overwhelmingly white working class community whose social and community life was still to a large extent organized along the traditional lines of church and labour movement.

The wider social and political context in which the CDPs operated – in hindsight the last days of the post-war social democratic consensus – was also very different. This period witnessed serious threats to the future well-being of local communities in areas like Benwell, but it also appeared to offer the potential transformation towards a fairer and more equal society. The CDP was both a product of and a contributor to this historical situation, and it is impossible to separate its work and impact from the wider context of social movements, organizations and activities, and their potential for radical change.

Setting up Benwell CDP

The project began in Spring 1972 with the appointment of the Action Director. From his desk in an outbuilding adjacent to Newcastle Civic Centre, Ian Harford was left to get on with assembling the project from scratch with little guidance or support from the Council:

I was just thrown in and had to make my own way. There had been no preparation, and the area in which the project would operate had not yet been chosen. I have no idea how the negotiation took place between the City Council and the Home Office but my overriding impression was that they had little understanding of what the intention of the project was or what the social and economic issues were that should be of interest to people who were being brought in to work on these projects. There was no discussion of any of this, but neither did they put any obstacles in my way. (Ian Harford, interview, 2016)

In line with the model of action–research decreed by the Home Office, all twelve CDPs shared the same basic structure. Each had an action team employed by the local authority in whose area the project operated. When Benwell CDP started, Newcastle City Council was Conservative controlled, although the wards targeted by the project were all represented by Labour councillors. In 1974, overall political control shifted to Labour in the context of a major local government reorganization that significantly extended the boundaries of the city of Newcastle. Every CDP also had a research team employed by an institution of higher education. Initially, Benwell CDP was linked with Newcastle University, but it soon became apparent that the project did not fit with either the university's dominant social work perspective or its positivist model of evaluation and, after prolonged negotiations, responsibility for the research team transferred to Durham University.

Benwell's core action team of director and two assistant directors was in place by early 1973, but the difficulties encountered in finding an acceptable institutional home for the research led to delays in establishing the research team. It was not until well into 1974 that the full complement of core research and action staff was in post. The research team comprised three researchers, one of whom had already been with the project for more than a year under the management of Newcastle University. The transfer of responsibility for the research team to Durham University offered an opportunity to shape the research capacity to include specific skills and knowledge relevant to the areas of work already prioritized by the project, and the two new appointments brought specialist economic and social research and housing and planning expertise into the project team. The staffing complement also included two administrative support workers, one employed by the council and the other by the university.

CDPs had sizeable budgets which enabled them to employ other staff to carry out particular roles. These included a number of key appointments of people with specific skills required to extend the expertise and capacity of the project team as the work developed. Among the earliest of these was a specialist information and advice worker, later joined by a second full-time advice worker and several sessional workers and, in 1974, by a professional lawyer. The project's research capacity was increased by the appointment of a research assistant, supplemented by several short-term contracts for specific pieces of research. The title ‘Community Development Project’ can be misleading. Only three of the Benwell team had a background of paid work or any relevant qualifications in the community development field, although others had experience of working in communities in a voluntary capacity or as part of a previous job. The rest of the staff came from a variety of backgrounds including youth work, teaching, law and community relations as well as research. The CDP had no formal training or induction scheme, and people picked up their community organizing skills on the job.

The initial phase of work focused on contacting local residents largely through traditional community work methods of door-knocking and talking to people in shops, clubs and elsewhere. In this way, they began to identify local concerns such as the appalling conditions endured by residents stranded in clearance areas, the hazards caused by traffic in residential areas and the deficiencies of the bus services. The project also set up a grant fund called The Benwell Ideas Group (BIG), giving a budget to a collective of local residents’ and tenants’ associations to make small grants to local organizations. BIG helped to embed the project in a network of local community groups and gained goodwill, but some painful lessons were learned, for example, when a van purchased for use by a local organization was never seen again.

Recognizing the need for a base in the heart of Benwell, the project took over former shop premises on the main street, Adelaide Terrace. While these were being refurbished, the team occupied a temporary base in the local library. The ground floor of the new premises became an open-access space for people to drop in. A welfare rights and advice service operated from here and it housed reprographic equipment for use by local groups and organizations as well as by the project team. Upstairs were meeting rooms and office space for the full team including the researchers and lawyer.

Perspectives and influences

By 1974 the Benwell team, in common with several other CDPs, had come to question the Home Office's model of action–research. The distinction between action and research roles had largely been jettisoned, disregarding formal lines of accountability and individual job descriptions. The research staff worked directly with local residents, helping to set up tenants’ associations, campaigning for housing improvements and supporting other forms of community action. Meanwhile, research and data-gathering were seen as important elements of the work of the action team. Influenced by critical theories such as those of Habermas (1972), the project adopted a view that research should be based in action and action needed to be theoretically informed. These perspectives were not developed in isolation but were informed by and contributed to the growing popularity of political economy analyses (Shaw, 1973).

The project had also by 1974 rejected the hierarchical structure envisaged by the Home Office and replaced this by a more democratic model of collective working (Darwin and Green, 1975). Although the extent to which the realities of everyday working adequately reflected the aspiration for a genuinely equal and collective democratic practice can legitimately be questioned, particularly in relation to issues of gender and power (Green and Chapman, 1992), the aspiration was shared by a number of other local CDPs and reflected a more general enthusiasm for experimenting with more democratic and egalitarian forms of organization that was typical of the times.

Although the national coordinating arrangements originally envisaged by the Home Office never functioned effectively (Loney, 1983), the CDP programme in practice was more than the sum of the twelve local projects. For the Benwell team, while the primary focus and commitment was on the local area, the importance of belonging to a high profile national project cannot be underestimated. This was in part a matter of the inspiration, intellectual stimulation and practical help that came from workers in other projects. Perhaps more significant was the fact that the project genuinely took seriously its remit of understanding the causes of localized poverty and identifying appropriate solutions. It was not acceptable to view the structural causes of poverty as too big for a local project to tackle, or to focus simply on mitigating local effects.

It is impossible to understand the role and impact of the CDP without recognizing the extent and diversity of other activity and organizations committed to developing radical alternatives at that time. As well as the local tenants’ associations, workplace organizations, action groups and numerous other organizations and networks linking local actions and campaigns, there were Newcastle-based radical organizations such as the Tyneside Socialist Centre (with its associated bookshop called Days of Hope after a 1975 BBC television drama directed by Ken Loach) and national organizations such as the Conference of Socialist Economists (CSE) and the grassroots history movement.

There was also considerable overlap between CDP workers’ paid work and their personal and political activities. All members of the Benwell team lived in Newcastle, most within the west end of the city, and were involved in local cultural and political life as both residents and workers. Most were members of the Labour Party, participating actively at all levels and occupying posts such as Political Education Officer in the local constituency which provided opportunities to promote local debate about the policies required to address the area's problems, as well as encouraging local residents to become active in political structures as another route to influencing plans and decisions affecting their lives. Involvement in trade union activity was another area of significant overlap. One of the community workers, for example, played a major role in the local National Association of Local Government Officers (NALGO) branch, editing a radical branch newsletter and organizing campaigns against public sector cuts. Team members were also involved in the wider cultural life of the city, seeing this as an extension of their CDP roles as well as a personal preference, for example, in the campaign to reopen Newcastle's independent Tyneside Cinema when it closed during the 1970s (Chaplin, 2011).

Overview of the project's work: key issues and activities

Benwell CDP was an active and enthusiastic contributor to the CDP inter-project reports and also produced many short reports and briefing papers on local issues. In line with the underpinning action–research model, the reports were not seen as ends in themselves but as elements in wider strategies to bring about change, whether by supporting other organizations working towards common aims or through the dissemination of research findings in a form that might influence the processes of change in a positive direction in order to benefit Benwell and similar communities. The various reports produced by Benwell CDP jointly or on its own were firmly rooted in the experience of Benwell. It was grassroots action that occupied most of the team's time – practically based work intended to tackle problems directly affecting the local community. Curiously, a myth developed that the CDP workers spent their time sitting around and theorizing rather than doing hands-on work, as former CDP Assistant Director and community worker Gary Craig explains:

As a community development worker, thinking about it from the ground upwards, I did some fairly solid neighbourhood work. That's quite interesting because the CDPs were often attacked, particularly as we developed and published more analytical papers about the areas we were working in and the analysis we had developed. A lot of community development workers used to attack us and say, ‘All you are doing is undermining neighbourhood work’, and they didn't understand there was no sense in which we could have developed that kind of analysis without being heavily involved in neighbourhood work. And the neighbourhood work was the kind of foundation for what we were doing, whether it was with tenants’ groups or with local enterprises, you know from big multinational engineering companies down to small clothing sweat shops. (Gary Craig, interview, 2014)

The following sections offer a brief overview of the project's work, focusing on housing, employment, and rights and advice.

Housing

Work on housing issues probably accounted for the largest proportion of the work of the Benwell team, through grassroots contact, organizing, support and campaigning. The range of issues of concern to residents varied across the area. In the clearance areas, residents faced problems related to demolition and re-housing, while residents on newly built estates were suffering from poor quality construction and lack of facilities. Council tenants in a number of estates were fighting for improvements to their homes, and all shared concerns about the repairs system and council services. In many of the older neighbourhoods where housing was privately owned or rented, problems of disrepair and substandard amenities were common. The project helped to build residents’ and tenants’ organizations in several neighbourhoods and supported them in their campaigning efforts. Various tactics were employed including confrontation where it was deemed appropriate, such as when workers accompanied a group of residents from a demolition area who dumped half a dozen dead rats on the steps of Newcastle Civic Centre to gain publicity and shock the council into action (Gary Craig, interview, 2014). Campaigning work often involved research input such as resident surveys or information gathering about property ownership. Although primarily campaigning tools, much of the data collected were incorporated into local or national CDP publications to show the operations of the local housing market or provide critiques of housing policy (National CDP, 1976a, 1976b; Benwell CDP, 1978a, 1978b).

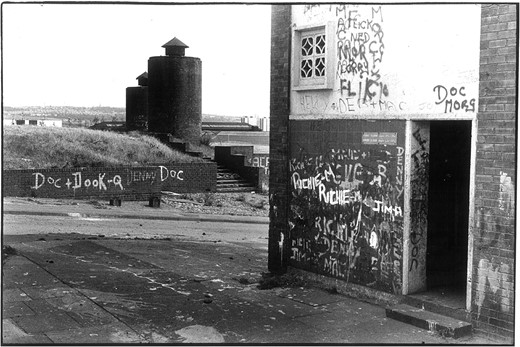

Noble Street flats on the right, with the capped shaft of the Beaumont Pit on the left (© Derek Smith, 1976)

Conditions in the privately built and owned terraces in the North Benwell and High Cross neighbourhoods, which had recently been removed from the clearance programme, were also a cause for concern. The CDP helped residents to organize and press for improvements to their homes and environment, arguing that the physical deterioration of housing was both a problem for residents and a symptom of wider contradictions in the housing market, the system of housing finance and government policy (National CDP, 1976b). As with the companion reports about industry and employment, the housing reports offered a detailed history and analysis of private housing in Benwell, using a wealth of primary source materials such as contemporary newspapers and ownership records as well as the experience of local residents.

Benwell CDP actively encouraged the building of wider tenants’ organizations. Together with other local community projects, the CDP supported the formation of one of the earliest tenants federations in the country. Newcastle Tenants’ Federation aimed to bring together the many active tenants associations in Newcastle. It was managed directly by those local associations and dedicated to campaigning and grassroots community action. The Federation went on to link up with other similar organizations elsewhere and became a founder member of the Tenants’ and Residents’ Organization of England set up to raise the voice of council tenants nationally (Unison Newcastle City Branch and Newcastle Council for Voluntary Service, 2012).

Industry and employment

The CDP's industry and employment work also had at its heart the aim of supporting autonomous grassroot organizations not only to press for improvements locally but to combine in order to enhance their strength and capacity and to increase their influence on national policy. From an early stage, Benwell CDP had recognized the need to focus on employment as an issue for research and action (Benwell CDP, c1973). At first, the assumption was that this would involve pressing for new well-paid jobs to be attracted into the area to replace those being lost from the declining local industries. This reflected the prevailing belief that Vickers, the company that had been the foundation of the area's spectacular growth over the past century, was now in decline. In 1974, the project linked up with a number of other CDPs to commission a report about the major companies that dominated employment in each of their areas (Moor, 1974). This was the start of a process of detailed local research into the changing economic base of each area, leading to the production of a national report examining the experience of five contrasting areas where traditional industries were undergoing major structural change – vehicle manufacture in Saltley (Birmingham), docks in Canning Town (London), the textile industry in Batley (Yorkshire), shipbuilding in North Tyneside, and armaments and heavy engineering in West Newcastle (National CDP, 1977a). It became evident that what was happening was not some inevitable process of decline but a result of global corporate restructuring. Vickers was not a dying company but a thriving multinational, expanding overseas while actively disinvesting from its West Newcastle location. The term ‘multinational corporation’ is in common usage today but the phenomenon had only recently been recognized in the early 1970s, and the notion that they were part of a wider process of globalization was not generally understood.

In a detailed report on the situation in West Newcastle (Benwell CDP, 1978c), the CDP warned that current trends indicated a future of persistent high unemployment and reduced incomes as a result of factory closures and cutbacks, compounded by the growth of the service sector and the impact of new computer-based technologies. This was intended as a warning of a potential crisis rather than a definite prediction and, if anything, the CDP underestimated the speed and thoroughness of the deindustrialization of the area and wider North East region in the coming years. In the light of subsequent events, it is perhaps hard today to understand the extent to which CDP workers were essentially optimistic in their outlook. Against a background of thirty years’ experience of the welfare state and near full employment, and in the midst of a plethora of social movements promoting greater democratization, equality and social justice, it seemed reasonable to assume that the forces of positive change could prevail. The point of the CDP's action–research was to contribute to this process of change by supporting local and national action to offset the trends they identified.

In this spirit, the project aimed to contribute to the wider debate about the ownership and control of British industry (National CDP Inter-project Report, 1975). Although the analysis and recommendations for policy and action contained in The Costs of Industrial Change might be viewed today as unrealistically radical, at that time they represented a respectable position within a serious mainstream debate about the future of British industry and the economy as a whole, as exemplified by the comments by Judith Hart, then the government's Industry Minister, in her foreword to the report:

This Report is to be read by all those who are about to engage in the debate…. (These conclusions) derive from an impeccable historical analysis…. It is about the whole direction our society is to take to meet the human need. (National CDP Inter-project report, 1977a).

As well as producing reports, the project used other strategies to communicate its findings and concerns about the future of employment and industry at a local level, including organizing meetings, giving talks and running adult education courses in partnership with the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) and others. The project sought to influence local councils to adopt a more interventionist stance on economic development rather than relying on provision of small business units and publicity about the attractions of Newcastle as a location. It was also involved in local campaigns, offering research and practical support to groups fighting redundancies and factory closures, such as the workers at Tress Engineering who battled unsuccessfully against the closure of their factory by the multinational company Fairey (Tress Shop Stewards, c.1978). This often involved what a former CDP worker called ‘a kind of counter-information job, just making it clear how profitable many of these companies actually were’ (Gary Craig, interview, 2014).

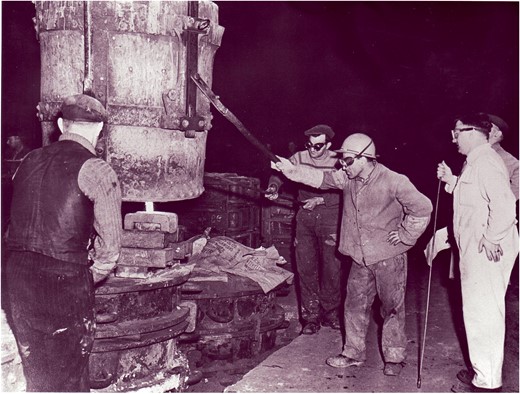

Vickers factory, c.1955 (© West Newcastle Picture History Collection)

The CDPs have been criticised, with some foundation, for focusing on male employment and under-valuing women's issues – a criticism that can be applied to much of the politics and social action of the period. However, the Benwell project did undertake work in support of women workers, particularly in the local clothing industry where low pay and part-time and casual working were prevalent (Nursery Action Group and Benwell CDP, c. 1977). Legislation on Equal Pay and Sex Discrimination was only introduced in Britain during the mid-1970s, and real equality still seemed a distant dream during the CDP period. As well as working with women in local workplaces to explore what was needed to make this happen, the project worked with women in the community, supporting local groups campaigning for childcare and holiday play schemes for children of working mothers. The project contributed to wider campaigns for women's rights, such as the Working Women's Charter (North Tyneside CDP, 1978; Armstrong and Banks, 2017). Benwell CDP also paid attention to public sector employment, participating in anti-cuts campaigns led by public sector unions, which they supported in practical ways such as producing briefing papers and offering access to reprographic and other resources. They sought to build alliances between local community groups and public sector workers to protect and improve services.

Welfare rights and legal services

A common feature of the twelve CDPs was the early establishment of advice and rights services, although the approach varied between areas. Benwell's open-access advice and information centre was very popular from the outset. According to former advice worker, Sue Pearson (interview, 2014), it was ‘inundated with people who had problems with income, problems with housing’. Initially every project worker took turns on the advice desk, but this was discontinued as it was felt that the benefits of offering specialist welfare rights expertise outweighed arguments for collective sharing of responsibility and community engagement. Other workers, however, continued to provide individual advice and information as part of particular campaigns such as that in the Noble Street flats. As Sue Pearson (interview, 2014) noted, Newcastle City Council was strongly supportive of advice work:

Because the council were relatively sophisticated they could see that it was a good thing. They understood the argument that if you improve people's income, you get them somewhere decent to live, they spend that money in the local community so the local economy benefits. Those ideas were quite revolutionary at the time.

Thousands of individuals used the advice services, raising a variety of problems of which benefits and housing issues predominated. While casework clearly achieved significant improvements for individuals, the project's experience mirrored that of the other CDPs in that it effectively faced a bottomless pit of need (National CDP, 1977b).

Although local people used the service primarily as individuals, the project's collective approach coloured the way the service was delivered. For example, the advice desk was deliberately located in an area used as a general public space as well as a waiting area for other clients, in the belief that the problems people were experiencing should be shared. Privacy and confidentiality were not seen as issues. Moreover, the provision of advice to individuals, while clearly valuable to those affected, was not seen as an end in itself. It gave the project insight into problems affecting the local community and in many cases led to follow-up action in the form of research, campaigning or community organizing. For example, evidence of the problematic operation of the social security system was used to inform campaigns, usually in collaboration with other groups and agencies. Successes included the Campaign Against High Heating Costs in Newcastle, set up in 1975 by a group of workers from the CDP and other community-based organizations together with tenants’ representatives, which helped to bring about changes in government codes of practice (National CDP, 1977b).

The Benwell project was one of six CDPs to appoint a professional lawyer to increase the range of skills and expertise of the staff team. In order to protect the independence of the lawyer, and his ability to pursue legal actions against the Council that funded his work, he was employed and managed by a separate organization called Benwell Community Law Project. Its committee comprised representatives of local residents’ associations and trade union branches as well as the City Council and the local Law Society, and it was chaired by the union convenor of the Vickers Scotswood factory. Employing a lawyer to work in a deprived community was not a novel idea, although it was new to Newcastle and caused some bemusement and even hostility within the local legal profession and its professional body the Law Society. At this time, legal practices were concentrated in the city centre and rarely dealt with areas of law such as housing and social security that particularly affected the residents of more deprived areas. The Law Centres movement had begun in London and was gradually extending across the country, but the nearest Law Centre to Benwell was 150 miles away.

The Benwell CDP lawyer did not generally undertake individual casework, except where this might assist a wider campaign or community action. He worked alongside other members of the CDP team on issues such as housing, employment and welfare rights with trade unions, tenants’ associations and other community groups. The project did not completely reject the idea of offering legal advice to individuals, but it did this by means such as organizing a rota of local solicitors and involving law students from the local university – although it proved difficult to find people competent to advise on areas of law alien to most legal practitioners at that time. Freedom from the treadmill of on-demand casework allowed the project lawyer to take a more strategic approach to community problems. In this model, using the law was one tactic among many that could be employed to bring about change.

An important part of the Law Project's work was advising groups of workers on employment rights and redundancy payments, including non-unionized groups such as the scaffolders working on the new Eldon Square shopping centre, who fought a protracted and bitter campaign following the loss of their jobs as a result of fighting for improved conditions. Among many examples in the housing field was the work with residents in a mixed tenure area of Elswick living in properties badly affected by damp and other unpleasant conditions. Working with the residents collectively, the lawyer successfully took proceedings on a number of test cases against the Council for its failure to take enforcement action to remedy the defects. Other examples illustrate how the Law Project became involved in areas of law and problems that were outside the CDP's mainstream work but were judged to be important because there was no other source of legal support available locally at the time. Working with the Bangladeshi community and the Community Relations Council, the lawyer challenged Immigration Office actions and helped to develop wider campaigns involving Newcastle Trades Council and other organizations. Another example was the work with local and national travellers’ groups to resist evictions and highlight the Council's failure to fulfil its legal obligation for adequate site provision.

Benwell's lawyer, David Gray, later recalled the innovative nature of this work:

These were areas of law that lawyers and clients did not really perceive as legal. People did not understand that they had rights and, if they thought they might, it was a major social barrier to visit a city centre lawyer's office. I recall quill pens still being used by some in Newcastle when I started. So in the 1970s it was almost like inventing new areas of legal practice in housing, social welfare, immigration, and challenging local and central government decisions by legal action. At the time we were the only ones in the region attempting this. It was virtually impossible to limit our areas of law to housing and benefits, and certainly to the West End. (David Gray, personal communication, 2016)

The work of Benwell Law Project had a wider legacy in terms of its contribution to a greater awareness of rights and a more holistic approach to problems. However, the CDPs themselves concluded that legal action was in itself insufficient to bring about the changes needed for their communities. A detailed analysis of the impact of the law on CDP areas highlighted its limitations as a tool for change, concluding that the law offered local people little protection against decisions that damaged their lives (National CDP, 1977b).

Elements of practice

CDPs were able to be innovative partly because their relatively generous budgets gave them scope to experiment in creative ways. This final section highlights some distinctive features of the Benwell project's work and the realities of community-based action–research in the 1970s.

Doing research in the 1970s

It is difficult for anyone born at a later date to envisage what was involved in doing detailed empirical research before computers and the internet. Without Wikipedia or Google, collecting even the most simple information involved extensive legwork such as visiting libraries, and identifying and talking to potential informants. Official statistics and other public information such as census data and company records had to be hunted out and scrutinized in a physical form in libraries and other institutions. There was no Ancestry or other search sites for obtaining information about births, marriages, deaths or wills, so this sort of information (vital for the production of reports on property development or business activities locally, for example) had to be tracked down in Registrars’ Offices and other places in different locations. There were no online newspaper sources, so the older ones had to be read in hard copy in libraries while current newspapers were read on a regular basis and cuttings files maintained by the project on subjects such as local companies and economic forecasts. Records of council proceedings had to be read in libraries or council basements. Photocopying facilities were rare and digital cameras and scanners did not exist, so such research involved extensive note-taking.

Some data were gathered directly from residents, but this tended to be integral to the ongoing process of making contact and involving people, as well as assembling information from multiple sources to form a picture of what was happening in the area. However, the project did carry out a number of formal surveys, including one looking at households’ experiences of employment and unemployment, which underpinned the analysis in the publication Permanent Unemployment (Benwell CDP, 1978c) and used random sampling, questionnaire schedules and sessional interviewers. Such work relied on what were effectively craft skills, learned through systematic training and experience, as there were few ‘how to do it’ research methods manuals.

Data analysis was time-consuming, though fortunately calculators had recently become available eliminating the use of slide rules and log tables. Most analysis was done manually, but larger data sets such as surveys required the use of a computer. Benwell CDP used Newcastle University's mainframe computer, one of the few in existence in Newcastle at that time (St James’ Heritage & Environment Group in partnership with West Newcastle Picture History Collection, 2014, pp. 30–31). This was a labour-intensive process, involving transfer of data onto coding sheets from which an army of women (and they were all women) punched holes in cards to be fed through a machine linked to the university's computer, eventually producing tables of results on long screeds of paper.

Dissemination and publicity

Considerable thought went into the planning and design of the Benwell final reports and the associated inter-project reports in order to make them accessible to a wider audience than the usual academic one. Their design, resembling a magazine format, was quite innovative in the 1970s when research was usually presented as dense text without illustrations. In the pre-digital age, printers used type-setting, producing galley proofs which then had to be corrected by hand.

The Benwell project produced many short publications in-house, mainly for local audiences, such as shorter versions of the big reports on housing, employment and other subjects and, for a period, an illustrated newsletter called Benwell: News and Views from Benwell CDP. The technology was scissors-and-paste, with headings created using letraset (sheets of letters which could be transferred manually by placing the sheet over the document and rubbing the required letter with a pencil). Photographs could be added by having the originals converted to ‘half-tones’ (combinations of black and white dots) prior to being stuck into the document, which was then printed elsewhere. Benwell invested in a state-of-the-art machine which could copy images as well as text and etch them onto a stencil ready for printing. The finished product looks rough and ready now, but seemed very smart in the 1970s and enabled the rapid on-site production of more attractive newsletters and leaflets.

The project also possessed a small home-made silkscreen press from which it manually produced large colourful posters through a laborious and messy process which could sometimes be risky, as when one a worker inadvertently used caustic soda to clean off paint from the screen and had to be rushed to hospital. This work was inspired by the iconic posters created during the May 1968 uprising in Paris. Among the local groups using the silkscreen press was the High Cross Residents’ Association, which ran two poster campaigns about the need for improvements to their homes. Tyneside Claimants’ Union also produced a set of posters advertising their activities. A single poster printed on the press still exists as part an exhibition about the history of Newcastle's independent Tyneside Cinema (Chaplin, 2011, p. 86).

In addition to printed outputs, the project used other media including video at a time when this was very rare (Benwell CDP, No date). The video recording machine was portable but large and heavy – about the size and weight of a big suitcase packed with books – with two reels of tape the size of dinner plates. Editing involved manually splicing and sticking tape together. For a period, the video equipment was put to good use. Tenants in one clearance area made a film about the conditions they were living under in order to show people in the next clearance area the sorts of problems they would be facing, while others used video to express their concerns about the problems experienced on a newly built estate. The CDP compiled newsreels about local events and issues which were shown at various local venues. A sample of this can be viewed online (West End News – re-housing Benwell, http://archiveforchange.org, accessed 24 October 2016). As the worker brought in to develop video for the Benwell project reflected recently, it was

a very interesting experiment in trying to not only use media other than what we saw as fairly dry reports and reporting other people, but actually allowing people not only to talk for themselves on video but actually get them to make the videos themselves. So we were trying to animate rather than control. And I think that's very much part of the times … of trying to break the patronising top-down type of organisation. And that fitted very much into the CDP idea. (Nick Sharman, interview, 2016)

The CDP also used drama to communicate ideas and reach wider audiences, including supporting a production by Belt and Braces, a national radical theatre group. Working with local shop stewards, they created a play about the fortunes of the local engineering industry as part of the campaign to save local jobs and promote debate about ownership and control.

Conclusion

This article has attempted, through a description of aspects of the project's work methods and practices, to provide insights into the complexities and challenges of the ‘action–research’ approach adopted by Benwell CDP. It shows that the project was clearly of its time both in terms of the resources and technologies available to it, and in the more fundamental sense of the wider context of radical activity and aspirations in which it operated. Does this mean that it is simply a historical curiosity or does the CDP's experience have lessons for today?

It would be difficult and contentious to attempt to pin down the CDP's legacy for the local community, not only because, as already emphasized, much of the work was undertaken in partnership with other organizations, but also because the impact of small, short-term initiatives can be at best marginal in the wider context of the enormous economic, social and political changes that have taken place since 1972. It is possible to point to particular improvements achieved in housing conditions, such as the modernization of the still popular Pendower Estate, for example, or to individual organizations that were set up as a direct result of the CDP's work, some of which are still in operation today such as Search's resource centre for older people or Newcastle Law Centre which is the direct descendant of Benwell Community Law Project. However, there are more examples of failure or loss. These include the almost total demolition during the 1990s of other housing areas in which the project had worked, and the closure of the West End Resource Centre, the organization that continued some of the CDP's work in Benwell after 1978 but which was closed within ten years as a result of spending cuts, leaving one of the most deprived areas of Newcastle without any welfare rights and benefits service.

The most obvious enduring legacy is the series of published reports produced by the Benwell project alone or in collaboration with other CDPs or other organizations. These demonstrate the value of detailed and rigorous empirical research, and are still regarded as well produced and well researched.1 They also offer a distinctive model of research in the service of social change, using an explicitly historical approach which highlights both the barriers and potential for change associated with any given period. The experience of the CDP raises continuing questions about the role of academic research, and whose interests it serves, which are as relevant today as they were in the 1970s.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on my longer paper Whatever Happened to Benwell CDP?http://stjameschurchnewcastle.wordpress.com/cdp-booklets/ Thanks are due to former CDP colleagues, especially Bob Davis and David Gray for contributing material and comments, and Ian Harford, Gary Craig, Sue Pearson and David Gray for participating in interviews carried out by Durham University as part of the Imagine research project; Sarah Banks, Andrea Armstrong and Mick Carpenter for editing and providing feedback on earlier drafts; Derek Smith for permission to reprint CDP photographs; and people too numerous to name who generously gave their time, memories and personal archives.

Funding

This article draws on interviews undertaken during 2013–2016 as part of the ‘Imagine – Connecting Communities through Research’ project, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant no. ES/K002686/2). Further details of the Imagine North East project can be found in Armstrong, Banks and Craig (2016).

Footnotes

Some reports can be purchased from St James’ Heritage and Environment Group (see website: http://stjameschurchnewcastle.wordpress.com) and some are available in digital form online at http://ulib.iupui.edu/collections/CDP.

References

Author notes

Judith Green was a researcher with Benwell CDP during the 1970s, and has continued to work in the west end of Newcastle up to the present day, currently in a voluntary capacity. She is an Honorary Research Fellow at Northumbria University. She coordinated the involvement of community organizations for the Imagine North East research project.