-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Linda Dong Ling Wang, Wendy Wing Tak Lam, Joseph Tsz Kei Wu, Richard Fielding, Chinese new immigrant mothers' perception about adult-onset non-communicable diseases prevention during childhood, Health Promotion International, Volume 30, Issue 4, December 2015, Pages 929–941, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau029

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Many non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are largely preventable via behaviour change and healthy lifestyle, which may be best established during childhood. This study sought insights into Chinese new immigrant mothers' perceptions about adult-onset NCDs prevention during childhood. Twenty-three semi-structured interviews were carried out with new immigrant mothers from mainland China who had at least one child aged 14 years or younger living in Hong Kong. Interviews were audio taped, transcribed and analysed using a Grounded Theory approach. The present study identified three major themes: perceived causes of adult NCDs, beliefs about NCDs prevention and everyday health information practices. Unhealthy lifestyle, contaminated food and environment pollution were perceived as the primary causes of adult NCDs. Less than half of the participants recognized that parents had responsibility for helping children establish healthy behaviours from an early age to prevent diseases in later life. Most participants expressed helplessness about chronic diseases prevention due to lack of knowledge of prevention, being perceived as beyond individual control. Many participants experienced barriers to seeking health information, the most common sources of health information being interpersonal conversation and television. Participants' everyday information practice was passive and generally lacked awareness regarding early prevention of adult-onset NCDs. Updated understanding of this issue has notable implications for future health promotion interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the most important causes of death in the twenty-first century, with over 60% of global mortality attributable to NCDs: cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes together accounting for around 80% of all NCDs deaths (WHO, 2011). However, a significant fraction of adult-onset NCDs are to a great extent preventable via eliminating shared risk factors, mainly unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking and harmful alcohol use (Gotay, 2005; WHO, 2011). Since these common risk factors are largely behavioural, WHO suggests NCDs prevention should be targeted at the level of family and community (WHO, 2011). Most of the health-damaging behaviour determinants of adult-onset NCDs are established early in life, with many modelled during childhood (Chen et al., 2001; Nadeau et al., 2011). Empirical studies evidence the difficulty of altering well-ingrained health behaviours among adults (Matarazzo, 1984), whereas health behaviour change theoretically could be easier and more effective for children (Epstein et al., 1995). Clinical evidence suggests many diseases processes responsible for adult-onset NCDs, such as atherosclerosis, begin early in childhood (Feigin et al., 2009). Therefore, beginning primary prevention efforts for adult-onset NCDs during childhood and adolescence utilizes a critical window of opportunity to teach health promoting behaviours.

However, previous studies regarding adult disease prevention during childhood have tended to focus on healthcare practitioners' attitudes and practices as well as exploring possible interventions (Pratt and Tsitsika, 2007; Berenson et al., 2010). Surprisingly, few studies have explored parental perspectives; yet parents are among the most powerful influences on children's early life and behaviour development (Hill and Trowbridge, 1998; Kiess et al., 2001). Existing studies on parents' perceptions of children's health issues which may contribute to future adult diseases have overwhelmingly focused on children's weight and obesity, and how parents' feed their children (Parry et al., 2008; Rietmeijer-Mentink et al., 2013). To our knowledge, no studies have examined parental perceptions and beliefs about adult NCDs prevention during childhood.

Hong Kong has one of the longest life expectancies of any country or territory in the world (LiveScience, 2012). Nevertheless, NCDs account for most of the disease burden in Hong Kong. In 2006, around 61% of registered deaths in Hong Kong were attributed to the four major preventable NCDs (CHP, 2012). NCD risk factors, such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and tobacco use, and the resulting disease clusters are more common among economically and socially disadvantaged groups (CHP, 2012). As an immigrant society, the major source of Hong Kong population growth is immigrants from mainland China. Other than a small number of professionally qualified and investor migrants, the bulk of mainlander immigrants (around 50 000 annually) comprise One-way Permit (OWP) holders who are spouses and dependent children from cross-border marriages with Hong Kong permanent residents, the majority of whom are of low socioeconomic status from Guangdong Province. (HAD & IMMD, 2011). New immigrants hereafter refers to OWP holders who have been living in Hong Kong less than 7 years (the minimum eligibility period for Hong Kong permanent residency), who are often less well educated, employed in low skilled jobs or unemployed, with lower income, and tend to settle in lower socioeconomic districts of the city (C&SD, 2012). Additionally, since most new immigrant adults are females, and in most households mothers control or directly provide childcare (Keitel, 2000), therefore, our study focus on new immigrant mothers to seek insights into how Chinese new immigrant mothers perceive adult diseases prevention during childhood.

METHOD

Study design and sample

The inclusion criteria for subject recruitment specified ethnic Chinese women living in a Hong Kong household who migrated from mainland China to Hong Kong no more than 7 years prior to interview, and who had at least one child aged 14 years or younger. Using purposive sampling, participants were initially recruited through referral from local NGOs and healthcare centres providing support services for new immigrants. Thereafter, snowballing to recruit friends and acquaintances of the original group was used to recruit more potential participants who met specific inclusion criteria. No new information from three consecutive interviews signalled data saturation and cessation of sampling.

Data collection

Participants were invited to complete a semi-structured one-to-one interview. Interview locations were determined by participants where they felt would maintain their privacy and convenience. All participants were informed about the study purposes and procedures. After participants gave written informed consent, interviews were conducted and audio taped. Interviews began with participants being asked about their thoughts regarding adult-onset chronic diseases. Respondents were encouraged to talk about their perceptions of causes of adult NCDs, preventive methods and then prevent adult diseases by action during childhood. Participants were lead to describe health information sources they used, and related practices they adopted were also explored using questions and prompts. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin by a female interviewer (LDLW, a native Mandarin speaker from mainland China). Each participant was offered a HK$100 (∼US$13) gift voucher for their participation on interview completion. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB).

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim in an ongoing process during the data collection and analysed using a Grounded Theory approach (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). The transcripts were studied intensively to explore new or unanticipated issues raised by previous interviewees, which could then be explored in subsequent interviews, a process helping maximize coverage and exhaust the range of related issues. Data were broken down, interpreted, conceptualized and reorganized. To maximize the validity of qualitative data analysis, two investigators independently coded the data and joint interpretive discussions were held. Disagreements were resolved by repeated textual reference, comparison and discussion, and, where necessary hierarchy re-assembly and re-coding. QSR NVivo 10, a software package designed for qualitative data analysis, was used to facilitate the sorting and classification of textual elements into related categories and themes.

RESULTS

Twenty-three new immigrant mothers participated between October 2011 and May 2012. Interviews lasted between ∼30 and 80 min. Participants' ages ranged from 27 to 50 years old with a median of 34 years. Fifteen (65%) participants had lower secondary education or below, approximating to the 60% proportion of female new immigrants aged 15+ achieving lower secondary as their highest education level (C&SD, 2012). Sixteen participants had monthly family income less than HK$14 070 (∼US$1800), the median monthly domestic household income of new immigrant households in 2011(C&SD, 2012). The majority of participants were OWP holders, a profile comparable to the general picture of female new immigrants in the 25–44 age groups (C&SD, 2012). About 50% of the participants had resided in Hong Kong for less than 4 years (Table 1).

Participant characteristics

| Code . | Age (years) . | Marital status . | Birth place (Province) . | Children's age range (months, years) . | Employment . | Educational attainment . | Period of settlement in Hong Kong . | Family income (HKD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM 1 | 36 | Married | Guangdong | 5 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 1 year | ∼4000 |

| IM 2 | 33 | Separated | Guangdong | 4 years | None | No schooling | 3 months | ∼3000 |

| IM 3 | 34 | Married | Hunan | 2 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1.5 years | 17 000 |

| IM 4 | 43 | Married | Jiangxi | 14–15 years | None | Primary | 7 months | ∼6000 |

| IM 5 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 7–9 years | Self-employed | Upper secondary | 6 years | 17 000–20 000 |

| IM 6 | 33 | Married | Sichuan | 7 years | Part-time job | Lower secondary | 4 years | 10 000–15 000 |

| IM 7 | 34 | Married | Hubei | 10 months–9 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | 30 000–40 000 |

| IM 8 | 44 | Widow | Jilin | 7 years | None | Lower secondary | 2 years | 4000–5000 |

| IM 9 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 5–10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 10 | 41 | Married | Guangdong | 6–8 years | None | Primary | 5 years | 13 000 |

| IM 11 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 6 years | Part-time job | Post-secondary | 4 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 12 | 50 | Married | Jilin | 13–23 years | Housewife | University | 4 years | >30 000 |

| IM 13 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–9 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | ∼20 000 |

| IM 14 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 2–8 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼12 000 |

| IM 15 | 33 | Married | Guangdong | 4–8 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | 5000–6000 |

| IM 16 | 39 | Married | Guangdong | 2–6 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | 8000 |

| IM 17 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–13 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 4 years | ∼8000 |

| IM 18 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–6 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 2 years | 9200–9800 |

| IM 19 | 38 | Married | Hunan | 1.5–16 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼7000 |

| IM 20 | 29 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | ∼13 000 |

| IM 21 | 27 | Married | Guangdong | 1 months–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 1 year | ∼8200 |

| IM 22 | 31 | Married | Guangdong | 4 year | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1 year | ∼12 000 |

| IM 23 | 36 | Married | Jilin | 10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 6 years | 20 000 |

| Code . | Age (years) . | Marital status . | Birth place (Province) . | Children's age range (months, years) . | Employment . | Educational attainment . | Period of settlement in Hong Kong . | Family income (HKD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM 1 | 36 | Married | Guangdong | 5 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 1 year | ∼4000 |

| IM 2 | 33 | Separated | Guangdong | 4 years | None | No schooling | 3 months | ∼3000 |

| IM 3 | 34 | Married | Hunan | 2 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1.5 years | 17 000 |

| IM 4 | 43 | Married | Jiangxi | 14–15 years | None | Primary | 7 months | ∼6000 |

| IM 5 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 7–9 years | Self-employed | Upper secondary | 6 years | 17 000–20 000 |

| IM 6 | 33 | Married | Sichuan | 7 years | Part-time job | Lower secondary | 4 years | 10 000–15 000 |

| IM 7 | 34 | Married | Hubei | 10 months–9 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | 30 000–40 000 |

| IM 8 | 44 | Widow | Jilin | 7 years | None | Lower secondary | 2 years | 4000–5000 |

| IM 9 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 5–10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 10 | 41 | Married | Guangdong | 6–8 years | None | Primary | 5 years | 13 000 |

| IM 11 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 6 years | Part-time job | Post-secondary | 4 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 12 | 50 | Married | Jilin | 13–23 years | Housewife | University | 4 years | >30 000 |

| IM 13 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–9 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | ∼20 000 |

| IM 14 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 2–8 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼12 000 |

| IM 15 | 33 | Married | Guangdong | 4–8 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | 5000–6000 |

| IM 16 | 39 | Married | Guangdong | 2–6 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | 8000 |

| IM 17 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–13 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 4 years | ∼8000 |

| IM 18 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–6 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 2 years | 9200–9800 |

| IM 19 | 38 | Married | Hunan | 1.5–16 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼7000 |

| IM 20 | 29 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | ∼13 000 |

| IM 21 | 27 | Married | Guangdong | 1 months–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 1 year | ∼8200 |

| IM 22 | 31 | Married | Guangdong | 4 year | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1 year | ∼12 000 |

| IM 23 | 36 | Married | Jilin | 10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 6 years | 20 000 |

Participant characteristics

| Code . | Age (years) . | Marital status . | Birth place (Province) . | Children's age range (months, years) . | Employment . | Educational attainment . | Period of settlement in Hong Kong . | Family income (HKD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM 1 | 36 | Married | Guangdong | 5 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 1 year | ∼4000 |

| IM 2 | 33 | Separated | Guangdong | 4 years | None | No schooling | 3 months | ∼3000 |

| IM 3 | 34 | Married | Hunan | 2 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1.5 years | 17 000 |

| IM 4 | 43 | Married | Jiangxi | 14–15 years | None | Primary | 7 months | ∼6000 |

| IM 5 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 7–9 years | Self-employed | Upper secondary | 6 years | 17 000–20 000 |

| IM 6 | 33 | Married | Sichuan | 7 years | Part-time job | Lower secondary | 4 years | 10 000–15 000 |

| IM 7 | 34 | Married | Hubei | 10 months–9 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | 30 000–40 000 |

| IM 8 | 44 | Widow | Jilin | 7 years | None | Lower secondary | 2 years | 4000–5000 |

| IM 9 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 5–10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 10 | 41 | Married | Guangdong | 6–8 years | None | Primary | 5 years | 13 000 |

| IM 11 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 6 years | Part-time job | Post-secondary | 4 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 12 | 50 | Married | Jilin | 13–23 years | Housewife | University | 4 years | >30 000 |

| IM 13 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–9 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | ∼20 000 |

| IM 14 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 2–8 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼12 000 |

| IM 15 | 33 | Married | Guangdong | 4–8 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | 5000–6000 |

| IM 16 | 39 | Married | Guangdong | 2–6 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | 8000 |

| IM 17 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–13 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 4 years | ∼8000 |

| IM 18 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–6 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 2 years | 9200–9800 |

| IM 19 | 38 | Married | Hunan | 1.5–16 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼7000 |

| IM 20 | 29 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | ∼13 000 |

| IM 21 | 27 | Married | Guangdong | 1 months–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 1 year | ∼8200 |

| IM 22 | 31 | Married | Guangdong | 4 year | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1 year | ∼12 000 |

| IM 23 | 36 | Married | Jilin | 10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 6 years | 20 000 |

| Code . | Age (years) . | Marital status . | Birth place (Province) . | Children's age range (months, years) . | Employment . | Educational attainment . | Period of settlement in Hong Kong . | Family income (HKD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM 1 | 36 | Married | Guangdong | 5 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 1 year | ∼4000 |

| IM 2 | 33 | Separated | Guangdong | 4 years | None | No schooling | 3 months | ∼3000 |

| IM 3 | 34 | Married | Hunan | 2 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1.5 years | 17 000 |

| IM 4 | 43 | Married | Jiangxi | 14–15 years | None | Primary | 7 months | ∼6000 |

| IM 5 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 7–9 years | Self-employed | Upper secondary | 6 years | 17 000–20 000 |

| IM 6 | 33 | Married | Sichuan | 7 years | Part-time job | Lower secondary | 4 years | 10 000–15 000 |

| IM 7 | 34 | Married | Hubei | 10 months–9 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | 30 000–40 000 |

| IM 8 | 44 | Widow | Jilin | 7 years | None | Lower secondary | 2 years | 4000–5000 |

| IM 9 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 5–10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 2 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 10 | 41 | Married | Guangdong | 6–8 years | None | Primary | 5 years | 13 000 |

| IM 11 | 34 | Married | Guangdong | 6 years | Part-time job | Post-secondary | 4 years | ∼10 000 |

| IM 12 | 50 | Married | Jilin | 13–23 years | Housewife | University | 4 years | >30 000 |

| IM 13 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–9 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | ∼20 000 |

| IM 14 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 2–8 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼12 000 |

| IM 15 | 33 | Married | Guangdong | 4–8 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 4 years | 5000–6000 |

| IM 16 | 39 | Married | Guangdong | 2–6 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | 8000 |

| IM 17 | 38 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–13 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 4 years | ∼8000 |

| IM 18 | 32 | Married | Guangdong | 8 months–6 years | Housewife | Lower secondary | 2 years | 9200–9800 |

| IM 19 | 38 | Married | Hunan | 1.5–16 years | Housewife | Primary | 4 years | ∼7000 |

| IM 20 | 29 | Married | Guangdong | 1.5–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 2 years | ∼13 000 |

| IM 21 | 27 | Married | Guangdong | 1 months–5 years | Housewife | Primary | 1 year | ∼8200 |

| IM 22 | 31 | Married | Guangdong | 4 year | Housewife | Lower secondary | 1 year | ∼12 000 |

| IM 23 | 36 | Married | Jilin | 10 years | Housewife | Upper secondary | 6 years | 20 000 |

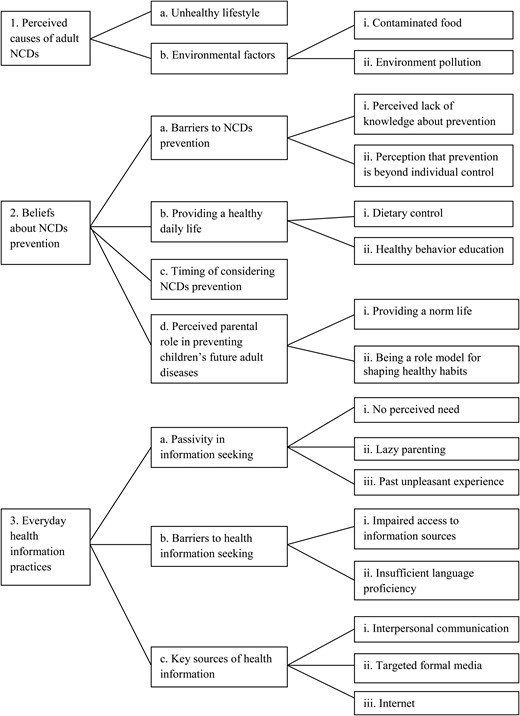

The present study identified three major themes: mothers' perceived causes of adult NCDs, beliefs about NCDs prevention and everyday health information practices. Figure 1 summarizes the relationship of themes, categories and components. The precise numbers and proportion of participants expressing each view are not provided as such data are not meaningful in a sample of this size. Illustrative quotes are provided to exemplify categories and components.

Theme 1: perceived causes of adult NCDs

As in Hong Kong, mainland China is also facing a rapidly growing challenge from NCDs (He et al., 2005). Cancers along attribute to around 3.5 million new cases and 2.5 million deaths annually in the mainland (He and Chen, 2012). In Guangdong Province, cancer, heart disease, respiratory disease and cerebrovascular disease are the leading causes of deaths (Wei et al., 2002). This was acknowledged by most participant mothers. Regardless of education level, participant mothers identified two groups of factors they perceived as important primary causes of adult-onset NCDs generally, subsumed under categories of unhealthy lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Unhealthy lifestyle

Almost all participant mothers understood the role of unhealthy lifestyle in NCDs and perceived elements thereof, particularly unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, as the primary cause of general NCDs, particularly towards CVDs and diabetes.

Now they do much less physical exercise, eat too much meat and sugar, (and so they) will have these problems. (IM18)

Some new immigrant mothers commented on different dietary habits and physical environment between Hong Kong and mainland China, and felt that greater sugar consumption and unhealthy diet, plus physical inactivity in Hong Kong contributed to various diseases.

There are more diabetes and hypertension (cases) here than in (the) mainland, just because they eat fried food, those McDonalds, and drinks, here people eat everything with sugar. (IM19)

You know, now kids in the city do very (much) less exercise, not like in the mainland (where) school children are required to do gymnastics at morning, or play ball, many activities. Here (there is) no place to do it (exercise). (IM17)

Few participants mentioned the harms of smoking while some related smoking mainly to respiratory diseases/cancers, suggesting parents had inadequate knowledge about the wider impact of smoking on, for example circulatory health.

Such as those of pneumonia, throat inflammation, ah, and the tumor of the trachea, mostly caused by smoking, and, nose cancer is also because of smoking too much. (IM15)

Environmental factors

Besides individual health-damaging behaviours, environmental factors as external causes, primarily contaminated food and environment pollution were regarded as important contributors to adult NCDs, particularly adult-onset cancers.

Contaminated food

Food safety, especially relating to illegal food adulteration and use of additives, is a growing concern among the public, particularly in China. Many participants expressed concern about contaminated food.

I think, probably because of the food. Now they use too many farm chemicals … And those farm pigs and chicken, all are vaccinated. It must have side-effects. (IM11)

Environment pollution

Awareness of environ-ment factors in human health, frequent media coverage of air pollution, water pollution in mainland China and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, probably contributed to environment pollution and radiation being perceived by some participants as important causes of adult-onset cancers.

It is also related to environment. Because now, you see the factories in Mainland, the polluted water, and the radiation, for instance the radiation of nuclear power from Japan after the earthquake, all these have effect on people's health. (IM17)

Theme 2: beliefs about NCDs prevention

Many participant mothers felt helpless and perceived significant difficulties in preventing adult NCDs based on their understanding of the causes. Participants shared similar views on daily activities for health maintenance, whereas views regarding the timing of NCDs prevention and perceived parental roles in children's NCDs prevention differed.

Barriers to NCDs prevention

Perceived lack of knowledge about pre-vention.

Many participant mothers expressed helplessness about NCDs prevention citing perceived lack of knowledge about disease prevention in response.

I don't know how to prevent. I only know that for lung cancer, less smoking can prevent it. Hum, I know drinking (alcohol) is not good for stomach. And diet, just eat less fried food, there is no good prevention, I don't know how to prevent. (IM11)

Perception that prevention is beyond individual control

Mothers who primarily attributed NCDs to harmful environmental factors were more likely to express helplessness and perceive difficulties in preventing NCDs since these health-damaging external factors are perceived as beyond an individual's ability to control and therefore inevitable.

Hey, no way to avoid it. You have to buy and eat it as you live here, otherwise have to die. Ah, no way of prevention. (IM15)

One participant mother expressed pessimistic beliefs regarding NCDs prevention, justified through comparison to socioeconomically advantaged prominent people and celebrities whom, she assumed, would have adopted healthier behaviours, and yet were still stricken by NCDs. A particular example mentioned frequently by many participants was Anita Mui, a Cantopop diva and actress, who several years ago died of cervical cancer, aged 40.

You see those famous stars, how rich they are? They must have regular body checkup every year, she (Anita Mui) still suffered. Some people seemed healthy, he (an acquaintance of the participant) did exercise every day, but still cannot prevent it. It is difficult to prevent, I think. (IM20)

Providing a healthy daily life

Based on their expressed beliefs about causes of adulthood NCDs, all participant mothers agreed that daily healthy practice is important. Preventive measures taken by many mothers mainly focus on daily dietary control and educating young children in healthy behavior.

Dietary control

A basic health-maintenance strategy expressed by many participants was dietary control, which involved preparing ‘healthy’ meals for family and controlling children's consumption of certain foods, such as sugar-sweetened soft drinks and snacks, reflecting the importance of diet in health for Chinese people.

I don't know (any) others. I only know one point, cooking with less sugar, salt and oil, which is the commonest knowledge. (IM11)

Usually we don't buy soft drinks and snacks for them, many are sugar-sweetened. Just ask them drink water instead, and eat more fruits. (IM12)

Healthy behaviour education

Besides controlling children's diet, some participant mothers also made efforts to encourage their children in outdoor play. Some participants, though not all who had sons, did provide education on prohi-biting smoking. Interestingly, no participants who had daughters mentioned advising their daughters not to smoke. This may reflect parents' misperception that only boys are likely to take up smoking habits, despite the increasing trend of female smokers (COSH, 2010).

I taught them to do more exercise. Because our living space is small, we often go to the park for running, sliding, or climbing stairs. Let them run and sweat, which is good for health. (IM15)

… . always remind him not to smoke. For instance, when we go to see doctor, many hospitals in mainland have posters displaying how the lung changes if smoke. Tell him the lung will become black like this if you smoke. Just teach him in this way. (IM9)

Timing of considering NCDs prevention

A number of participant mothers had no clear sense about early prevention of adult NCDs which seemed too far in the future to be an issue for them, whereas children's immediate health was overwhelmingly important to those parents.

I haven't thought about this aspect. Because, their present health is more important for me, such far future issues … I didn't think so much. (IM7)

In contrast, some participants, particularly those more educated, having good understanding of the importance of establishing healthy habits during childhood, perceived that NCD prevention should start early in life.

While (they are) young, we should start to prevent, don't wait until they grow up. Because, their diet habit and sleep habit, are all initiated at a young age. (IM15)

Perceived parental role in preventing children's future adult diseases

Although all participants unanimously acknowledged parents play an important role in children's health, different views were revealed regarding parental roles in preventing children's future adult-onset NCDs.

Providing a normal life

Most participants stated that as parents they had great responsibility for providing a normal healthy environment for children and taking care of their present health, especially emphasizing regular meal times, and similar quantities of food being consumed at each meal. However, some participants did not perceive the provision of healthy environment as serving to prevent future diseases for their children, and they did not perceive this as a parental responsibility. This possibly reflects a knowledge gap about the development of these diseases beginning in early life.

Parents' responsibility, such as whether to give them good care and a regular diet, these are parents' responsibility. But regarding her future diseases prevention, I think it is not our responsibility. We just try our best to do good things for them, which is enough. (IM21)

… adulthood diseases, that is, you have grown up and become an adult, all these (diseases prevention) will depend on your own (actions). Because you are already mature, then you should prevent these (diseases) by yourself. (IM14)

Moreover, some participants who emphasized monitoring and control of children's healthy behaviours rather than cultivating children's healthy habits, often perceived that parental control of children's behaviour and health will start to weaken and eventually disappear during adolescence and adulthood. This may be why some participants focus on children's current health.

Presently I try my best to take care of her. Future … ? It is difficult to say. I cannot prevent (things in the future). When she is mature I cannot control her anymore. (IM6)

Being a role model for shaping healthy habits

Some participants were well aware of the likely impact of healthy habits on diseases prevention, and believed children's health behaviour largely depends on the degree to which parents educate them. These mothers thus perceived parents should play a key role shaping children's behaviour for diseases prevention in present and later life.

Parents have to help them establish good habits since they are young. A child is like a piece of white paper, depends on how parents write on it … You have to model her habits while she is young, and then she won't be too outrageous after growing up. (IM8)

Theme 3: everyday health information practices

Information practices are ‘a set of socially and culturally established ways to identify, seek, use, and share the information available in various sources’ (Savolainen, 2008). Here, health information practices refer to practices to identify, seek, use and share health-related information in daily life contexts. Chinese new immigrant mothers' everyday health information practices were almost exclusively passive, and relied heavily on limited, mostly informal, sources of information. Three categories comprised new immigrant mothers' perceived health information seeking: (a) passivity in information seeking; (b) barriers to health information seeking; (c) key sources of health information.

Passivity in information seeking

Many new immigrant mothers interviewed expressed little interest in taking the initiative to seek health information. This was frequently associated with the lack of perceived need, lazy parenting and past unpleasant experiences.

No perceived need

Most participant mothers expressed less interest in seeking health infor-mation so long as their children appeared healthy. Some participants judged their children's health status by monitoring their appetite, which again reflects the role of diet in health for Chinese people.

Our understanding (of being healthy) is … (based on) appetite. If she (the daughter) can eat well, (her body) can absorb the nutrients … (This is) then good enough. (IM8)

Lazy parenting

A number of participant mothers attributed the reasons hampering active information seeking to lazy parenting, even when recognizing information need or knowledge gaps relating to their child's health promotion, perhaps because parents generally perceived their young children were already healthy.

For example, flu shot, I am not sure whether to vaccinate him, and I didn't ask others. Feels like I am lazy, usually I don't raise questions, just drag it out. (IM20)

Actually it is good to find some information about maintaining health if you have time. For example, what you should eat at cold days, or what soup is good for health in summer. Usually (I) just hear from others, or occasionally watch from TV, but never deliberately seek these (information), maybe because of laziness. (IM11)

Past unpleasant experience

Some participants experienced discouragement associated with uncomfortable feelings, including embarrassment or ignorance, stemming from difficulty in health information seeking and then reluctantly coped passively by ‘letting it go’.

Perhaps it's their (nurses') style of talking, and because (there are) lots of patients there, they seemed very tired and reluctant to answer your questions. If they explained once but you didn't understand, when you asked again, they would be impatient … (IM4)

Firstly, we are not familiar (with how to find out things) here. Secondly, if you deliberately seek some health information, at that moment, I feel embarrassed. So, (I) just let it be. (IM1)

Barriers to health information seeking

As newcomers to Hong Kong, many participant mothers experienced difficulty when seeking health information due to lack of access, skills or insufficient language proficiency.

Impaired access to information sources

Many participants stated they did not know how and where to seek information. Nearly half of all participants had no access to computer or lacked Internet skills.

I don't know where to seek information. I am not capable of using internet, (I) never learnt it. Everyday (I'm) just busy in (the) house, (that's) life as a housewife. (IM20)

Insufficient language proficiency

Unlike mainland China, in Hong Kong Cantonese instead of Putonghua and more complex traditional rather than simplified Chinese ideograms are used. For new Mainland immigrants, especially those from non-Cantonese speaking provinces, language is an inevitable barrier to communication, with around 27% of new immigrants reporting difficulties in adapting to the language environment in Hong Kong (HAD & IMMD, 2011).

I can speak a little bit of Cantonese, but not so well. It is difficult for me to read traditional Chinese, just like an illiterate. (IM4)

Key sources of health information

The most commonly reported sources of health information were (i) interpersonal communication, particularly conversation with peers, (ii) targeted formal media, and (iii) Internet.

Interpersonal communication

Sharing daily health information among parents, peers and friends was both ad hoc and intentional during formal or informal meetings, such as might occur at parks, children's school, church and the workplace. This way new immigrant mothers gained unplanned and unanticipated but useful information. These informal social networks played a key role for new immigrant mothers in the context of their daily lives. Participant mothers described how they shared and gathered information through chatting with friends and fellow parents.

Sometimes when taking our kids to school, parents of schoolmates will gather together and chat. If I hear something is good for children, I will also try it. (IM10)

I have one friend working in the church. Sometimes she tells me which food (we) should and should not eat. Really, you won't know a lot of things if you cannot use Internet. Just like me, they will tell me what I don't know. (IM9)

Furthermore, when encountering problems relating to children's health, many participant mothers acknowledged they still preferred to ask peers or fellow parents rather than seek formal information elsewhere since the former often had similar-aged children and were ‘experienced’.

If the problem is common, such as catching a cold or cough, I won't ask others. If it is unusual, I will ask. For example, last time my daughter had some secretion which I thought was unusual, so I asked friends who are experienced, ask whether their daughter ever had similar problem. (IM5)

Sometimes kids are picky towards some food. I would ask other fellow parents why they don't eat. Ask whether their children at this stage also don't eat (specific food) and try to find out the reason. (IM20)

Targeted formal media

In addition to the use of interpersonal communication, participants also made use of health information from formal sources due to its timelessness and accuracy. The most common formal information sources are television followed by health education leaflets from children's schools or healthcare settings.

Sometimes there are health education programmes on TV, e.g. talking about diseases prevention or healthy diet, (so) following those instructions I often try to do it. And sometimes the Department of Health has some publicity pamphlets distributed to school children to bring (home), for instance, about (diet with) ‘Three High and One Low’. (IM9)

Health information, sometimes you can get the pamphlet from MCHC … and sometimes the children's school also distributes the leaflets. (IM19)

Internet

A subset of respondent mothers who are computer-literate usually preferred seeking infor-mation from Internet for convenience and comprehensiveness, particularly when encoun-tering a specific health concern or with specific intent.

Usually using internet, it is very convenient, you can find whatever you want. (IM7)

For those (information) not easily to be found, I used to seek (information) from internet because of convenience. You just need to type it. (IM9)

Sometimes seek (health information) from internet, hmm, for instance, what babies should eat, or the tips of food combination. Just like, the triangular pyramid diet, sometimes I will follow the triangular pyramid to prepare meal. (IM3)

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of parents' health information-seeking behaviour addressed mainly task-based or problem-specific information seeking (Knapp et al., 2011; Turner et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2012), whereas in order to manage daily lives mothers may need and seek information on a daily basis. Thus, everyday information practices are often habitual and arbitrary (Savolainen, 1995; Walker, 2012). This sample reported interpersonal communication and television were the most significant sources of everyday health information for new immigrant parents, consistent with the findings of a recent review study which showed social networks are the key sources of information for vulnerable and marginalized population like immigrants (Caidi et al., 2010). Meanwhile, immigrants are often at high risk with limited health literacy (Institute of Medicine, 2004; Kreps and Sparks, 2008), which reflects individuals' ability to obtain, process and understand health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (Institute of Medicine, 2004). The present study revealed that many participants encountered access or language barriers to information seeking. Many of these low SES participants lacked both personal computers at home and Internet search skills. Hong Kong government statistics indicate that in 2009 around 73.3% of households had home computer Internet access (C&SD, 2010). Given the increasing reliance on Internet-delivered information, including online healthcare appointment booking, many immigrants are unable to benefit. The limited and largely informal sources of health information used by new immigrant parents from disadvantaged families suggest that populations in economic poverty also experience information poverty (Chatman, 1996; Caidi et al., 2010).

New immigrant mothers rely heavily on passive information seeking. Informal interpersonal social networks are important influences on health behaviour (Liao et al., 2010, 2011). Television was the most influential broadcast media in this group. The reluctance to actively seek health information, attributed to perceived lack of need or ‘lazy’ parenting, coupled with a general passive approach to information may imply that young children and adolescents are considered to be a mostly healthy group who need no input. Negative experiences such as impatient attitudes from health care providers, or feelings of embarrassment may prompt passive or avoidant coping strategies despite dissatisfaction with information obtained. Heavy reliance on informal sources by immigrant parents likely reflects the social isolation and informal support networks that form among new members of a community; common language and immigrant status provide an identity and enables mutual support. This has implications for how community agencies or public health practitioners could more actively support and help build community networks and support groups, thereby increasing access to health information suitable for immigrant parents. Examples include community-based health education classes in Putonghua, information notices from children's schools and mass media including television.

Regarding the development of adult NCDs, almost all participants emphasized the role of unhealthy diet. Chinese culture traditionally emphasizes the importance of food as a source of illness and health (Koo, 1982). Many participant mothers limited their health-improvement efforts to providing healthy meals and restricting certain food consumption, sometimes coupled with encouraging active play. A previous study using card-sorting methodology similarly found that few parents ranked low physical activity as a top risk factor for children' health compared with other known risks such as diet (Hernandez et al., 2012). Chinese new immigrant parents while aware of high-risk feeding behaviours seldom recognized the risks from inactivity in their young child. In Chinese culture, ‘chubby’ children are thought to be more healthy (Cao et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2012), whereas increasingly chubby babies grow to be overweight children and adults (Baird et al., 2005; Gupta et al., 2012). A recent systemic review found more than 50% of parents cannot recognize when their child is overweight (Parry et al., 2008). Therefore, parents' inherent sense of what constitutes health is often inadequate to help them judge their children's best interests when it comes to preventing future NCDs, and reliance on this is likely to prove ineffective as a health strategy. Many participant mothers lacked clear knowledge about early prevention of adult NCDs. Some participants were aware that health-risk behaviour in childhood impacted on adult diseases development and strove to help their children establish health behaviours rather than simply concentrating on current health status, but many others did not. Therefore, interventions regarding adult-onset NCDs prevention starting in childhood should target both family and community groups.

Although medical knowledge is not a sufficient basis for health decision making, and increasing knowledge alone has marginal impact on behavioural change (Ajzen, 1991), however, behaviour-change theories (Becker, 1974; Ajzen, 1991) suggest improving knowledge is necessary to achieve relatively accurate health-risk perceptions. This should promote actively seeking and identifying relevant health information. Early health campaigns for NCDs prevention showed that simply focusing on health information education without considering individuals' socioeconomic status and health literacy fails to achieve expected outcomes (Nutbeam, 2000). Tailoring and distributing comprehensible and accessible health information for new immigrant and possibly other low SES parents in Hong Kong is therefore required for effectively reaching and influencing these groups.

A person's willingness to action is influenced by their motivation, perceived self-efficacy and behavioural control as well as the anticipated consequences of the action (Ajzen, 1991). Where parents perceive they have little control over their children's health in later adulthood or struggle to influence or maintain their children's health, they are likely less willing or able to take preventive action for children (Tinsley and Holtgrave, 1989; Ajzen, 1991). Establishing clear guidelines for healthy child-rearing to reduce risks of future NCDs should involve providing capacity building for parents and not just passive health education.

Study limitations include snowball sampling, which can restrict sample heterogeneity. Though participants were mostly of low-to-middle-class socioeconomic status and new immigrants tend to take up less skilful jobs in Hong Kong, having median monthly household incomes of only 68.6% of that for general households (C&SD, 2012), our study participants have comparable characteristics to the general new immigrant mothers. Moreover, the findings are consistent with earlier health behaviour decision-making studies of communicable disease prevention in Hong Kong (Liao et al., 2010, 2011). So there is good reason to believe that this study presents a valid and reliable picture of the situation faced by many of the fastest-growing demographic of new-immigrant families in Hong Kong.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored causal beliefs about adult-onset NCDs and perceptions towards adult NCDs prevention during childhood among new immigrant mothers from mainland China who had settled in Hong Kong. Chinese new immigrant mothers while generally aware of high risk of unhealthy lifestyle on the development of adult NCDs lack awareness of how this translates into adult NCDs prevention during childhood. Predominantly most new immigrant mothers showed passive information-seeking practices and often relied on limited sources of, mostly informal information, in particular interpersonal communication. Insight gained from this study will help inform healthcare providers in health communication and public health practitioners to develop future NCDs prevention and health promotion interventions taking into account of audiences' health literacy to assist the assimilation of this segment in a healthier community.

FUNDING

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the mothers who participated in the interviews. Thanks also to Hong Kong New Immigrant Service Association, International Social Service Hong Kong Branch and United Christian Nethersole Community Health Service (UCN) for supporting us through help recruiting participants.