-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marc E. Agronin, From Cicero to Cohen: Developmental Theories of Aging, From Antiquity to the Present, The Gerontologist, Volume 54, Issue 1, February 2014, Pages 30–39, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cicero’s famous essay “On Old Age,” written in ancient Rome, was one of the first detailed depictions of the challenges and opportunities posed by the aging process. Several modern developmental theories of the life cycle have echoed many of the themes of Cicero, including the existence of unfolding life stages with specific tasks and transitions. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of infantile sexuality provided a limited starting point, as well as a theoretical base for Erik Erikson’s proposed eight stages of the life cycle. Unlike Freud, however, Erikson and others including Daniel Levinson, George Vaillant, and Carol Gilligan elaborated on forces in adult development that were distinct from early life experiences. Gene Cohen’s theory of human potential phases took middle age as a starting point and proposed an extensive structure for late-life development based on emergent strengths including wisdom and creativity.

The Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero might well be considered the first gerontologist. In his lauded essay “On Old Age” published in 44 BC, Cicero captured the dialectal views of aging as perceived in ancient Rome (Cicero, 44 BC/1951). One the one hand, he extols our potential as we age: “The arms best adapted to old age,” he wrote, “are the attainment and practice of the virtues; if cultivated at every period of life these produce wonderful fruits when you reach old age” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 130). On the other hand, he warns of a predictable limit to this process: “Old age is the final act of life, as of a drama, and we ought to leave when the play grows wearisome, especially if we have had our fill” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 158). Cicero is praising an old age, which “is respectable as long as it asserts itself, maintains it rights, is subservient to no one” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 140). Once this striving reaches an endpoint, whether imposed by nature or self, the “weariness of life brings a season ripe for death” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 154).

Cicero is no doubt appealing here to the sentiments of the Greek and Roman era philosophy of Stoicism in which the ideal life was guided by reason and virtue and thus dependent on the integrity of the mind. Seneca, one of its greatest proponents, hinted at the futility of aging once dementia set in; “I shall make my exit,” he declared, “not because of the actual pain, but because it’s like to prove a bar to everything that makes life worthwhile” (Seneca, 1932). According to Minois (1989), this Stoicist perspective on the mental failures of old age may have been behind a rash of suicides among older Romans in the first and second centuries AD. Cicero nods to Stoicism without embracing it entirely, however. At a time when the average life span in Rome was likely in the late 20s, he portrays an attainable old age for some patricians (but for few plebians, no doubt) that echoes many themes of modern-day developmental theorists. For example, he speaks of stages of life, which have their own tasks, writing: “Life has its fixed course, and nature one unvarying way; to each is allotted its appropriate quality, so that the fickleness of boyhood, the impetuosity of youth, the sobriety of middle life, and the ripeness of age all have something of nature’s yield which must be garnered in its own season” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, pp. 138–139). He also discusses the importance of cultivating a sense of integrity in the final years, which is based on life review or on some other process of reckoning: “When the end comes what has passed has flowed away, and all that is left is what you have achieved by virtue and good deeds” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 152).

Psychodynamic Theories of Human Development: Freud and Erikson

For many centuries, Greek and Roman literature exerted the strongest influence on the social, moral, and literary perspectives on aging in Western culture. It was not until the late 19th century, however, that Cicero’s sentiments on aging were resurrected in any form of serious scientific inquiry (Cole, 1992; Minois, 1989). This may be attributable to the fact that the average life span did not fall into the realm of Cicero’s celebrated elders into well into the 20th century. In the early 1900s, Sigmund Freud postulated his psychoanalytic theory of developmental stages, but limited it to early childhood. His scheme is based upon a dynamic interaction between a child’s first biological instincts (i.e., to suckle, eat, and eliminate) and their external regulation. The newborn infant, for example, must form an oral bond with the mother’s breast in order to receive sustenance and soothing. This innate process of suckling faces pitfalls along the way as the maternal source is not always available, may be withdrawn by suckling too hard or biting, and eventually must yield to weaning. Thus, there is the inevitable experience of frustration, which tempers and sometimes overwhelms the trust of the young child, particularly under times of duress or in the presence of inadequate or even abusive caregivers. Relative successes or fixations in the three successive oral, anal, and phallic stages of childhood help to determine personality and lay the basis for later psychopathology (Freud, 1905/1964). In this scheme, the child is, in the words of the poet Wordsworth, the “father” of man. Later psychoanalysts such as the object relations theorists Melanie Klein and W. R. D. Fairbairn emphasized the psychic internalization of this infant–mother attachment (Gabbard, 2005) and extended it into adulthood, although without positing any truly new or independent forces in later life.

Freud focused very little on development in old age, and his few impressions appeared quite pessimistic. In his 1905 essay entitled “On Psychotherapy” he wrote: “Near or above the age of fifty the elasticity of the mental processes, on which the treatment depends, is as a rule lacking – old people are no longer educable – and, on the other hand, the mass of material to be dealt with would prolong the duration of the treatment indefinitely” (Freud, 1905/1964, p. 264). Of course, Freud was referring in a narrow sense to the use of psychoanalysis with older individuals, and perhaps did not mean to imply a general rule for late-life cognition. In fact, Freud himself defied his very pessimistic rule as he continued to be quite intellectually active until his death in 1939 at the age of 83.

Nonetheless, old age remained an unexplored territory for Freud and other early psychoanalysts. A broader focus on adult—but not geriatric—development began with a new generation of postwar analysts, including the noted child psychoanalyst Erik H. Erikson, best known for his writings on the human life cycle and theory of the eight stages of man (Erikson, 1950). Erikson was schooled in Freud’s theory of infantile sexuality, but found it inadequate to account for the role of social factors in shaping personality. He called this interaction between inner psychic structures and outer social forces a “psychosocial” process. For example, he described how the relative success of the “oral” relationship between infant and mother formed the basis for an individual’s unfolding sense of trust, first with the mother but later with other caregivers and social structures. Erikson emphasized that development continued as a dynamic process beyond childhood as ego-syntonic forces built upon and bolstered key strengths in each stage, whereas ego-dystonic forces tempered these achievements and threatened fixation and regression.

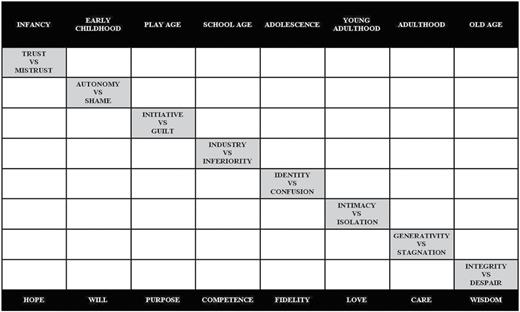

Through his clinical work with children and adolescents, Erikson expanded upon Freud’s original three stages and added five more, each with its own tension or “crisis” through which an individual navigated. The stages themselves were anchored in developmental milestones and named after the central tension, so the oral stage became “trust versus mistrust,” followed by “autonomy versus shame and doubt” for the toddler mastering toilet training, “initiative versus guilt” for the young child expanding the ability to wander and play independently, and “industry versus inferiority” for the child entering school. A schematic of Erikson’s stage theory can be found in Figure 1.

Erikson’s eight stages of the life cycle. The name of each successive stage appears along the top, the central tension appears diagonally across the middle, and the stage-specific strengths appear along the bottom. The diagram is based on Erikson (1950) and Erikson and Erikson (1997). Reprinted from Agronin (2010), with permission.

Erikson was best known for his fifth stage of “identity versus role confusion,” which characterizes the adolescent’s search for a coherent sense of self or “ego identity.” This evolving identity enables the emerging young adult to integrate previous experiences and self-notions with current impulses and social expectations. He coined the term “identity crisis” to account for this often tumultuous period of time (Erikson, 1950, 1968). Erikson’s sixth through eighth stages of adulthood have neither the Freudian foundation nor the detailed explication of the earlier stages, but they were influential as they represented one of the first modern stage theories of adult psychological development. Young adulthood is characterized by a search for intimacy versus isolation, whereas middle adulthood involves a drive toward generativity versus the perils of stagnation. Erikson describes generativity as involving “procreativity, productivity, and creativity . . . including a kind of self-generation concerned with further identity development” (Erikson & Erikson, 1997, p. 67). The first stages of adulthood were best represented in several of Erikson’s psychohistories of numerous historical figures, including Martin Luther, Mahatma Gandhi, Adolf Hitler, Maxim Gorki, Thomas Jefferson, and George Bernard Shaw (Erikson, 1950, 1958, 1968, 1969, 1974). His most detailed and best known psychohistory Gandhi’s Truth garnered the National Book Award in 1970.

As seen through these psychohistories, however, adult development was primarily refracted through the lens of one’s struggle for identity or “identity crisis” during late adolescence and young adulthood, which was itself refracted through earlier childhood stages. Erikson’s previous focus on the play configurations of children from his monumental first work Childhood and Society was morphed into a focus on the word configurations of adults, which “had the same bridge effect as the first, connecting inner psyche to outer social circumstances” (Friedman, 1999, p. 279). For example, in Young Man Luther, Erikson described how Martin Luther’s own identity crisis as a young monk served as the keystone event in the formation of not only his adult personality but his later spiritual break with the Catholic Church. Luther’s case, in particular, had magnificent implications in that it led to the establishment of Western Protestantism.

Though Erikson had postulated an eighth stage as representing a search for a sense of “integrity versus despair” during old age, it was not well developed, and in Young Man Luther “as Erikson’s narrative progressed from Luther as a young adult to Luther in midlife and beyond, his discussion became hurried and undeveloped” (Friedman, 1999, p. 285). Similarly with Gandhi’s Truth, Erikson focused mainly on the role of identify formation in the life and philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. In his biography of Erikson, Friedman (1999) described how Erikson’s own clinical work with adolescents and young adults both influenced and limited this focus.

Erikson’s first in-depth treatment of late life was a case history, but instead of a major historical figure he focused on the character of Dr. Isak Borg from Ingmar Bergman’s film “Wild Strawberries” (Erikson, 1978). Erikson often screened this film for students in his popular course at Harvard University because he described how he “found in this screenplay an incomparable representation of the wholeness of the human life cycle—stage by stage and generation by generation” (Erikson, 1978, p. 5). The film depicts several days in the life of the elder Dr. Borg, a Swedish physician who is journeying by car from his home to the University of Lund to receive an honorary doctorate marking 50 years of practice. His daughter-in-law accompanies him on the day-long drive, and they make several stops along the way to visit his aged mother and a vacation home on the coast where he spent many happy summers during his childhood. A trio of young hitchhikers joins them for part of the trip, and their lively presence and bickering provides what Erikson interprets as symbolic representations of the identity crisis. Throughout the trip, Dr. Borg engages in a cinematic life review through a series of recollections, dreams, and heart-to-heart conversations with his daughter-in-law, which traverse his entire life cycle. Without fully explicating old age itself, Erikson makes a larger point about its place amidst the other stages: “All the emergent strengths are necessary to complete the individual cycle . . . no such cycle can escape variable emphasis on the inhibiting and isolating qualities of human development which foster fear and anxiety . . . Neither Borg nor any other character is thus nearly ‘located’ in one stage; rather, all persons can be seen to oscillate between at least two stages and move more definitely into a higher one only when an even higher one begins to determine the interplay: thus, if Borg, in the last stage that can be formulated as developmental, is in a renewed struggle with the two earlier ones, he is so in the face of death or, at any rate, senility” (Erikson, 1978, pp. 28–29).

The first principle of old age that Erikson advanced in his case study of Dr. Borg (and in later case studies that grew out of Berkeley’ famous Guidance Study) was that it represents the culmination of the stages of the life cycle insofar as it integrates all of the strengths and weaknesses that came before it (Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1986). Of all of Erikson’s eight stages, it probably best represents the epigenetic principle, in which the developmental trends of life interact in multiple directions, which are based upon but transcend the underlying genetic or anatomic scaffolding. Thus, an individual “is never struggling only with the tension that is focal at the time. Rather, at every successive developmental stage, the individual is also increasingly engaged in the anticipation of tensions that were inadequately integrated when they were focal; similarly engaged are those whose age-appropriate integration was then, but is no longer, adequate” (Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1986, p. 39).

Erikson’s second principle of old age is that any sense of integrity must exist within a creative dynamic with “legitimate feelings of cynicism and hopelessness” that characterize the opposing ego-dystonic sense of despair (Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1986). Thus, I have written that “although cultivating a sense of integrity seems to be the only ideal pursuit in later life, Erikson’s framework is more supportive of a balance between syntonic and dystonic forces. This does not mean that a little despair is necessarily good, only that an unbridled sense of integrity without some realization of the limited horizon ahead can be problematic. The achieved balance in perspective—a recognition and tolerance of competing life forces and of the reality of death—is what Erikson aptly labeled wisdom” (Agronin, 2011, p. 75). Wisdom “maintains and learns to convey the integrity of experience, in spite of the decline of bodily and mental functions” (Erikson, Erikson, & Kivnick, 1986, pp. 37–38). It becomes the product of the dominant force of integrity in late life, even as it provides “informed and detached concern with life itself in the face of death itself” (Erikson & Erikson, 1997, p. 61). As a practical force in late life, it underlies the drive to be vitally involved as caregivers, role models, and guides for others across the generations.

This definition of wisdom is quite revealing of Erikson’s own views of aging as a struggle between positive growth and the growing awareness of one’s declining body. Erikson himself struggled with a number of age-related physical ailments, and in his 80s developed dementia—most likely Alzheimer’s disease. Consequently, in his last writings on the life cycle, his wife Joan assumed a much more active role not only in editing but in theorizing as well. In an extended version of his work entitled The Life Cycle Completed, she added a chapter outlining a ninth stage of development, which represents individuals in their 80s and 90s who are facing “new demands, reevaluations, and daily difficulties” (Erikson & Erikson, 1997, p. 105). As I have written, “much of their description of the ninth stage is quite gloomy as it depicts the unraveling of the life cycle due to bodily decline and the loss of autonomy, self-esteem, confidence, and ultimately of hope itself” (Agronin, 2010, p. 256).

To Joan Erikson, the ninth stage brought “much sorrow to cope with plus a clear announcement that death’s door is open and not so far away” (Erikson & Erikson, 1997, p. 113). She described how the despair of the eighth stage threatened to become the dominant force in the ninth, bringing with it the risk that a feeling of disdain or disgust will reign as “a reaction to feeling (and seeing others) in an increasing state of being finished, confused, and helpless” (Erikson & Erikson, 1997, p. 61). This engulfing despair, now applied wholly to this stage, was first described by Erikson as “the feeling that the time is now short, too short for the attempt to start another life and to try out alternate roads” (Erikson, 1950).

Post-Eriksonian Developmental Theories

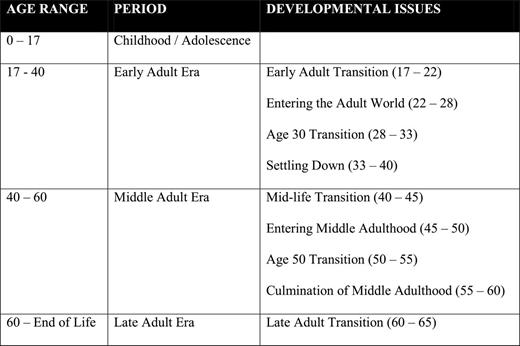

Several other developmental theorists have built upon Erikson’s writings about the life cycle in adulthood. In his seminal work The Seasons of a Man’s Life, Yale psychologist Daniel Levinson detailed early and middle adult tasks and transitions based upon longitudinal interviews with 40 individual men (Levinson et al., 1978). Interviews with women were published posthumously in The Seasons of a Woman’s Life (Levinson & Levinson, 1996). Levinson’s work differed from Erikson in several respects. First, Levinson did not anchor his theory in psychodynamic theory or in the central role of tensions or conflicts that emerge during successive stages. He postulated instead that major life transitions were influenced by evolving physiological, psychological, and role-oriented life changes. For example, the passage into middle adulthood occurred when “instinctual energies . . . pass their maximal level and are somewhat reduced . . . A man is by no means lacking in the youthful drives—in lustful passions, in the capacity for anger and moral indignation, in self-assertiveness and ambition, in the wish to be cared for and supported. But he suffers less from the tyranny of these drives” (Levinson et al., 1978, p. 25). Levinson echoes Cicero here, who also believed that an attenuation of instinctual drives would liberate more mature pursuits, because “Nothing for which you do not yearn troubles you” (Cicero, 44 BC/1951, p. 144). As Levinson described, “the modest decline in the elemental drives may, with mid-life development, enable a man to enrich his life. He can be more free from the petty vanities, animosities, envies and moralisms of early adulthood . . . He can become a more caring son to his aging parents . . . and a more compassionate authority and teacher to young adults” (Levinson et al., 1978, p. 25). A list of Levinson’s developmental periods can be found in Figure 2.

Another key difference is that Levinson’s developmental periods were based upon empirical research with adults, whereas Erikson’s stages were based on clinical work—mostly with younger individuals. As a result, Levinson’s stages and transitions hinged mostly on events within their chronological limits, whereas Erikson’s stages integrated potential and extant strengths and weaknesses from across the lifecycle. For example, whereas Erikson might describe a life event within the bonds of ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic forces, Levinson lets it stand-alone “as a marker indicating where he now stands and how far he can go. This culminating event represents some form of success or failure, of movement forward or backward on the life path” (Levinson et al., 1978, p. 31).

Like Erikson, Levinson’s focus was primarily on young and middle adulthood, and the concept of old age was poorly developed and stereotyped. For example, he posits late adulthood as a time when “a man can no longer occupy the center stage of his world . . . a man receives less recognition and has less authority and power. His generation is no longer the dominant one” (Levinson et al., 1978, p. 35). This waning of power and influence may be accompanied by the fear “that the youth within him is dying and that only the old man—an empty, dry structure devoid of energy, interests or inner resources—will survive for a brief and foolish old age. His task is to sustain his youthfulness in a new form appropriate to late adulthood. He must terminate and modify the earlier life structure” (Levinson et al., 1978, p. 35).

Like Levinson, Harvard psychiatrist George Vaillant based his stage theory both on Erikson’s work and on the longitudinal study of aging adults though his extensive empirical research as director of the Study on Adult Development at Harvard (Vaillant, 2002, 2012). “Like Erikson,” he wrote, “I have concluded that one way to conceptualize the sequential nature of adult social development may lie in appreciating that it reflects each adult’s widening radius over time. Imagine a stone dropped into a pond; it produces ever-expanding ripples, each older one encompassing, but not obliterating, the circle emanating from the next ripple. Adult development is rather like that” (Vaillant, 2002, p. 44).

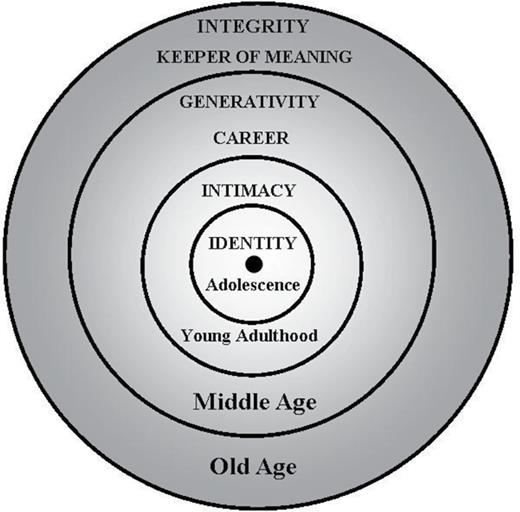

In contrast to Erikson, Vaillant’s own perspective moves away from emphasizing “stages” and instead focuses on the “developmental tasks” of life that are typically but not always sequential (Vaillant, 2002). Vaillant outlines how an adolescent’s main task is to establish an identity separate from his or her parents. Young adulthood brings the task of learning to sustain a mutual, committed relationship. In both young and middle adulthood, Vaillant stresses the role of career consolidation in which the individual is able to work at life’s chosen vocational tasks with appropriate sociability and a sense of satisfaction. Generativity grows out of one’s career and represents an expansion of purpose to be a leader for the next generation. Vaillant found in his longitudinal studies that successful generativity tripled the chances that an individual would experience more joy than despair in their 70s (Agronin, 2010; Vaillant, 2002). Vaillant’s scheme is illustrated in Figure 3.

Vaillant’s developmental tasks. Based on Vaillant (2002). Reprinted from Agronin (2010), with permission.

Old age is best represented by Vaillant’s fifth and sixth development tasks labeled “Keeper of the Meaning” and “Integrity,” respectively. These concepts bridge many of the tasks, which Erikson assigned to both generativity and integrity and involve a focus “on conservation and preservation of the collective products of mankind – the culture in which one lives and its institutions – rather than on just the development of its children” (Vaillant, 2002, p. 48). An older individual serving as the Keeper of the Meaning is generally less ideological because there is a widening and less selective circle of concern. His or her efforts and energies often allow for more meaningful intergenerational relationships because they tap into the enduring foundations of culture and history (Agronin, 2010). The last developmental stage of integrity echoes that of Erikson, indicating the necessary task of accepting and finding some meaning and ownership over what has come before in life, without succumbing to despair over the narrowing possibilities of age (Agronin, 2010).

Psychologist Carol Gilligan has critiqued Erikson, Levinson, and Vaillant for proposing theories based primarily on male development, where separation, individuation, and achievement are consequentially seen as the ideal endpoints (Gilligan, 1982). As she wrote in her seminal work In A Different Voice, “thus there seems to be a line of development missing from current depictions of adult development, a failure to describe the progression of relationships toward a maturity of interdependence” (Gilligan, 1982, p. 155). She further states that none of the case studies provided by any of the aforementioned theorists adequately supported the notion that separation or individuation led to or enhanced attachment and mutuality. Thus, “the reality of continuing connection is lost or relegated to the background where the figures of women appear” (Gilligan, 1982, p. 155). The missing voice of women’s development not only robs developmental theories of enormous datapoints but more fundamentally biases our thinking on the very trajectories of development.

Gilligan focuses primarily on the unique role of interpersonal connections in female development. Read from this more inclusive standpoint, Gilligan asserts that fundamental components of the life cycle such as identity must be expanded to “include the experience of interconnection” (Gilligan, 1982, p. 173). In contrast to the lives of many men, then, such a force may better lead women to develop a “maturity realized through interdependence and taking care” (Gilligan, 1982, p. 172). Although these forces were studied by Gilligan in young women (Gilligan et al., 1990), they have not been examined in the lives of aged women or men.

Gene Cohen’s Human Potential Stages

Gene D. Cohen was unquestionably one of the founding fathers of geriatric psychiatry, and an original thinker when it came to a modern conception of old age. Contrary to the developmental theorists discussed prior, Cohen’s approach started in middle and was not primarily concerned with what came before in the life cycle. Instead, he continued his stages throughout old age and to the end of life, focusing on the ever extant potential for growth that occurred not in spite of old age but because of it. A review of several seminal events from own life history illustrates how he came to many of his conclusions.

Cohen was born in Brockton, MA, in 1944. His first encounter with the concept of aging came at the age of 16 when he entered a prestigious science contest with a study he conducted on the age and growth norms of a local fish called the longhorn sculpin. This research taught him how the study of aging opened many new vistas because the data he collected on the fish reflected many aspects of the local oceanographic environment. After graduating from Harvard College in 1966 and Georgetown University School of Medicine in 1970, Cohen started his residency in psychiatry. In 1973, he was drafted into the U.S. Public Health Service and assigned to work at the National Institute of Mental Health, where one of his rotations involved working with elderly individuals who were living in a public housing unit in Washington, DC, called Regency House. Many of the residents suffered from chronic mental illness. Contrary to expectations, Cohen saw the incredible strengths in these individuals, stating that “Instead of what others warned would be the most depressing of patients, these elderly women and men proved to be among the most alert, attentive and responsive – a satisfying kind of patient for a doctor who cares” (Cohen, 2000, p. 126).

His keen eye saw the study of these aging individuals as a new frontier, and led him to propose and then assume leadership of the Center for Studies of the Mental Health of Aging at the National Institute of Mental Health in 1975. This center was the first federal aging institute in the United States and predated the establishment of the National Institute on Aging by about 6 months. His success in opening up interest and research into the study on aging came despite the admonitions of several supervisors that by pursuing the field he was throwing away his career and ought to be in psychoanalysis as a patient (Achenbaum, 2010). Cohen went on to help found the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry in 1978, becoming the first editor of the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry in 1992. In 1991, Cohen was appointed the acting director of the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health, and in 1994, he became the first director of George Washington University’s Center on Aging, Health & Humanities.

Throughout the arc of his career, Cohen developed several key concepts that promoted his later developmental scheme. He described how these concepts were supported by research into neuroplasticity showing how the brain is continually resculpting itself in response to experience and learning. One result is that our emotional circuitry becomes more mature and balanced as we age, leading to refinements of cognition, judgment, and social skills (Cohen, 2005). The integration and synergy of these maturing skills with both life experience and consciousness is what Cohen termed “developmental intelligence,” defined as “the degree to which an individual has manifested his or her unique neurological, emotional, intellectual and psychological capacities” (Cohen, 2005, p. 35).

Hand-in-hand with this developmental intelligence is the role of creativity, which Cohen asserted persisted and even grew with age, leading to new potentials and exploration. In his study of creativity, he came to doubt conventional wisdom that many aging artists faced a loss of creative vision as a result of a deterioration of physical dexterity and a fading willingness to try new things and take risks. In contrast, he observed how many artists maintained and even grew their own creative capabilities as they aged. Cohen first witnessed this at the Regency House, where he would sometimes see artwork in the apartments of his patients. During a visit to an exhibit of American folk art at the Corcoran Museum of Art in 1980, Cohen observed that 80% of the 20 exhibitors had started their art or reached a mature phase after the age of 65, and 30% were 80 or older (Cohen, 2000). He came to believe that “the secret of living with one’s entire being . . . is the creative spirit that dwells in each of us . . . It can occur at any age and under any circumstances, but the richness of experience that age provides us magnifies the possibilities tremendously” (Cohen, 2000, p. 17). Cohen emphasized that creativity played a dynamic role in building and managing relationships, in responding to adversity with new solutions and directions, and in promoting culture and the common good via intergenerational and community interactions (Cohen, 2000).

Cohen’s concept of wisdom was rooted in what many cognitive scientists refer to as postformal thinking, representing a developmental stage that lies beyond the terminal phase of formal operations that Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget theorized was achieved by adolescence (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Richards, 1982; Labouvie-Vief, 1982). Postformal thinking is characterized by the ability to understand and compare competing sets of relationships or systems, to think more relatively and less universally, and to appreciate the tension between one’s own perspective and that of other people or systems (Agronin, 2011; Nemiroff & Colarusso, 1990). Cohen sees distinct advantages to postformal thinking in middle and late-life transitions, noting how it helps us to “contemplate more than one answer to a problem, to consider contradictory solutions to life’s challenges, . . . and to make decisions based on a tighter integration of how we think and feel” (Cohen, 2005, p. 98).

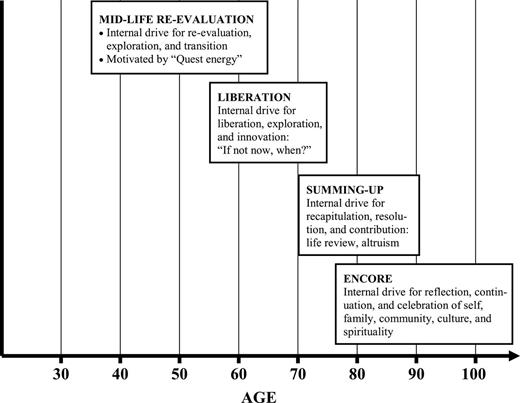

Cohen’s developmental scheme is thus derived from his thinking on the ability of late-life creativity and wisdom to “energize our creativity and jump-start our efforts to explore new ideas or make desired change” (Cohen, 2005, p. 7). He proposes a series of human potential phases, which “reflect evolving mental maturity, ongoing human development, and psychological growth as we age” (Cohen, 2005, p. 7). These phases are illustrated in Figure 4.

Cohen’s human potential phases. Based on Cohen (2005). Reprinted from Agronin (2010), with permission.

The first human potential phase is called the “midlife reevaluation phase,” which starts in the mid-to-late-30s and continues through the mid-60s. This phase, according to Cohen, involves newfound motivation to reevaluate one’s life and make positive changes using “quest energy.” A life example provided by Cohen is the author Alex Haley, who began a 12-year quest into his African American family history, culminating at the age of 55 in the publication of the best-selling book Roots. The “liberation phase” occurs in one’s mid-60s to mid-70s, and is characterized by a sense of needing to act now, often to engage in experimental or innovative activities that were not considered in the past. This phase is often supported by the new personal freedoms and creativity conferred in part by retirement. One of Cohen’s examples of this stage is former Senator Jim Jeffords of Vermont, who at the age of 68 switched his political party affiliation and thus altered control of the Senate (Cohen, 2005).

The “summing-up phase” occurs in one’s late 60s to 90s, and is energized by enhanced wisdom and a desire to contribute to the world. Resultant life activities often involve a search for a larger meaning in life. Cohen’s example is the dancer Martha Graham, who after retiring at the age of 75 put her energies into the choreography of several major new ballets and revivals up to her death at the age of 96. The “encore phase” occurs in one’s late 70s to the end of life, and is characterized by a drive for personal reflection and activities to restate, reaffirm, and celebrate the major themes in one’s life. Cohen illustrates the potential for this last stage to be vital and energetic by citing the example of the sisters Bessie and Sadie Delaney, who at the ages of 101 and 102, respectively, coauthored a best-selling story of their lives together (Cohen, 2011).

Quite distinct from other developmental theorists, Cohen proposed a method of enhancing one’s pathway through these phases called the social portfolio (Cohen, 2005). The social portfolio consists of an individualized list of vital activities that one can engage in along dimensions of low and high mobility and individual or group pursuits. It is based upon what Cohen cites as the reality of active and selective engagement in late life versus stereotypical and inaccurate theories of disengagement. Its creation is an activity that an individual engages in through an active review of one’s lifelong personal assets. Ideally, individuals assemble their portfolios with the participation of others who know them well. The social portfolio is meant to be diversified and include “insurance” in the form of vital activities that can be engaged in even in the face of disability or loss.

Summary

This tour of developmental theories has illustrated the age-old pursuit of a meaningful scaffold upon which to track experiences, transitions, and themes of the human life cycle. Perhaps most extraordinary are the elements common to all theories, in which emergent changes are anchored in our physical and mental maturing, with old age being a time of both decline and great potential. More than ever, we are seeing a new old age, brought to us in part by a major demographic shift in which more and more individuals are living into their 80s and 90s. In 2017, for the first time in recorded human history, the number of individuals on this planet who are 65 years or older is predicted to surpass the number of individuals less than 5 years old (National Institute on Aging, 2007). Societies throughout the world will thus be more old age-centric, and increasing numbers of individuals will live out the human potential phases of Cohen not unlike the few celebrated elders of Cicero’s era.

Funding

The activities of Dr. Agronin are supported in whole by the Miami Jewish Health Systems.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD