-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Koji Kanda, Yoshi Obayashi, Ananda Jayasinghe, G.S.P. de S. Gunawardena, N.Y. Delpitiya, N.G.W. Priyadarshani, Chandika D. Gamage, Asuna Arai, Hiko Tamashiro, Outcomes of a school-based intervention on rabies prevention among school children in rural Sri Lanka, International Health, Volume 7, Issue 5, September 2015, Pages 348–353, https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihu098

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In Sri Lanka, one of the major challenges in rabies control is to manage the dog population and subsequently to protect people, especially young children, from dog bites.

In 2009, an educational-entertainment campaign called ‘Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids’ was introduced in the school curricula in rural Sri Lanka to improve practices on rabies prevention and pet care among school children, and to evaluate its effectiveness through pre- and post-tests.

The level of rabies knowledge, attitude and practice among the pupils was dependent on their responses to a survey, and scores were significantly improved both among the study and control groups after the intervention. A lecture accompanied by a rabies awareness leaflet was much more effective in improving knowledge than the leaflet alone. The type of intervention and language used was significantly associated with the score increment (p<0.001).

The threat of rabies to pupils in Sri Lanka would be reduced if they are given appropriate information on rabies prevention as a part of the school curricula. Close collaboration with local education offices is key to successful implementation of school-based rabies control programmes, which is, in turn, crucial to the eradication of rabies from Sri Lanka.

Introduction

Rabies still remains a major public health issue worldwide, including Sri Lanka. Annually, there are estimated to be 55 000 human rabies deaths in more than 150 countries, and more than 15 million people receive post-exposure prophylaxis.1 Sri Lanka has the fourth highest human rabies death rate in the Southeast Asian region.2 A total of 1730 human rabies cases were reported in the last two decades (1991–2008).3 The number of confirmed cases has gradually declined from 136 in 1991, to 38 in 2012,3–4 however, there were 718 animal rabies positive cases recorded in 2012.4 Thus, more intensive interventions are needed in Sri Lanka to achieve the national target of rabies elimination by 2016.

In Sri Lanka, one of the biggest challenges in rabies control is to manage the dog population and subsequently to protect people from dog bites. Due to the 'no animal killing policy‘, the dog to human ratio was estimated to be 1:4.6 in suburban Colombo and 1:5 in Central Province.5–6 People feel frustrated with the excessive number of stray dogs in their communities.7 These high dog density environments have resulted in frequent animal bites causing severe physical injury.8 Approximately 5% of the general population in central Sri Lanka have experienced animal bites injuries. More than 80% of those who were bitten had transdermal bites, and nearly two-thirds of the injuries were unprovoked.9

Under such circumstances, children are most vulnerable to dog bites associated with rabies infection. Previous reports indicated that more than one-fifth of people bitten by animals were children under 15 years of age, and 27.6% of human rabies cases in Sri Lanka, in the last 8 years, occurred in those under 20 years of age.5,9 Also, pets in the home were responsible for three-quarters (77%) of animal bites.9 Even though local governments have several dog population management programmes, more sustainable and effective strategies are required for successful rabies control.

Rabies control strategies currently implemented include mass dog vaccination campaigns, dog population management, rabies laboratory diagnosis and surveillance and rabies awareness campaigns. However, increasing rabies awareness among those vulnerable in a community is one of the most cost-effective approaches for rabies prevention. Since evidence-based and effective communication tools for rabies control and prevention is widely available and easy-to-use in various settings,10 it is crucial that rabies management and control programmes be included in the curriculum of healthcare professionals.11

In the Philippines, for example, a pilot rabies information and education campaign has been successfully implemented as part of the school curricula in all elementary schools in a region.12 A similar study in Nigeria also showed that it is highly recommended to provide proper education on rabies among children.13 However, successful control programmes are often location-specific and substantial adjustments are often needed to replicate the programme with community participations in different locations.14 In multi-ethnic countries such as Sri Lanka, interventional programmes need to satisfy ethnic, religious and socio-cultural norms in order to maximise the outcomes of the programme and to minimise chances of implementation failures. Although local NGOs have implemented rabies awareness programmes for school children and the general public,15 such practices are rarely documented. Therefore, there is a need for systematic and sustainable programmes to be created in resource-limited settings.

Taking the above mentioned factors into account, as well as the recommendations of the WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia and policies as stipulated in Sri Lanka's Rabies Elimination Act of 2005,2 our aim was to improve practices on rabies prevention and pet care among children through an educational-entertainment campaign called ‘Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids'. This educational-entertainment campaign covered 125 grade five pupils and the effect of intervention was evaluated through pre- and post- tests among participants.

Methods

The study was conducted between January and March 2009 in Nuwara Eliya District, Sri Lanka. This district, one of 25 districts of Sri Lanka, is a rural mountainous area located in the middle of the country, and is a tea plantation area. Population in this district, in 2009, was estimated to be 755 000. As of the last census conducted in 2012, the Indian Tamil population in this district accounted for 53.2% of the population, an increase of 2.6% since the 2001 census.16

Study design

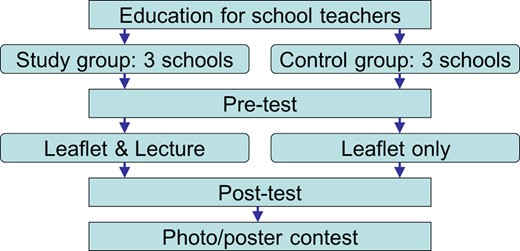

This is an interventional study to compare the level of improvement of rabies knowledge during the Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids campaign. It is a pilot awareness-raising programme among school children with active involvement from various sectors such as community, medical, veterinary, education, religious and/or local/national government. Under the supervision of educational, health authorities and academia, both school children, their families and teachers participated in various activities including photo captures, lectures, a poster contest and self-study on rabies prevention. Two methods were used to improve the knowledge: the first provided an original leaflet describing rabies prevention to promote awareness and the second involved a lecture on rabies prevention by school teachers, along with the leaflet. The study design is shown in Figure 1.

Study design of the educational-entertainment campaign called 'Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids’ introduced in school curricula in Nuwara Eliya District, Sri Lanka. This figure is available in black and white in print and in color at International Health online.

Participants and selection

With support from the Hanguranketha Educational Office and Health Department, we targeted grade five pupils currently attending public primary schools. The participating schools were selected by the local authorities from the Hanguranketha Educational Zone. Among the 227 schools in the province, four Sinhala-speaking and two Tamil-speaking schools were selected. There were no differences in the school curricula of the selected schools. Tamil-speaking schools were often located in more rural mountainous areas as many of the parents of children attending the schools worked in the tea plantations. A representative class in each school was selected and all the pupils in the class took part in the pilot study. A total of 125 grade five pupils participated in the study.

Procedure

The Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids campaign was composed of three phases. In the pre-implementation phase, primary-school teachers were requested to participate in a training session. They received an orientation of the rabies situation in Sri Lanka and developed rabies education and advocacy that would be part of school curricula during the study. They then prepared instructional materials and activity guides in their local languages (either Sinhala or Tamil) for use during teaching. During the implementation phase, 125 grade five pupils in six primary schools were divided into study and control groups by their class. The pupils participated in the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) surveys twice, with a 4-week interval. The KAP questionnaire consisted of four sections: about yourself; what do you know about rabies; which of these animals can carry rabies and responsible dog ownership. Each section contained three to eight questions answered by multiple choice, including yes-no and true-false responses. The questionnaire was first developed in English and then translated into Sinhala and Tamil by native speakers. After that, they were back-translated into English by different translators and tri-lingual speakers checked whether all questionnaires in all three languages were analogous. The self-administered questionnaire was anonymous, but students were asked to fill in their unique identification number so that the two questionnaires were connected during the assessment of the intervention. It took about 15 minutes for pupils to complete the questionnaire. No informed consent was obtained from the pupils, but their parents were informed about the purpose of the study. During the 4-week interval between the surveys, the study groups were given a lecture on rabies by their school teachers. The teachers used lesson plans, modules, instructional materials and session guides on rabies prevention in lessons covering all subject areas, and monitored pupils' activities and achievements through class observations. The awareness leaflet was given to pupils and used during and outside classes for their reference. Pupils in the control groups were only instructed to read the leaflet provided by their teachers, with no further follow-up information provided. In the post-implementation phase, we organised a poster and photo-capture contest for participating pupils to further enhance their interest in rabies prevention. Posters were made by school pupils using crayons, water colors, black-lead or colored pencils on A4 size paper and showed their understanding of responsible pet ownership and/or rabies control. Using digital cameras, pupils were given 1 hour to capture actual environmental situations related to the subject matter. Pupils showed the challenges that they saw and explained their role in helping to find solutions. Both posters and pictures were evaluated by judges, who included a community leader, a zonal educational officer and a religious representative. Winners of respective contest categories received prizes.

Data analysis

The analysis focused on the effect of the intervention by assessing the score difference between the two KAP surveys. The analyses included the frequency distribution, cross-tabulation and multiple linear regression. We obtained the knowledge score, which consisted of the responses to the eight statements and five questions on the possible mode of transmission. Data were analysed using EpiInfo Version 3.5.3 (CDC, Atlanta, USA).

Ethical review

This study was approved by the ethical review committee at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were nearly an equal number of males (64/125; 51.2%) and females (61/125; 48.8%) that participated in the study. Religion and ethnicity were highly correlated (56/58 Sinhalese pupils [97%] follow Buddhism, and 46/55 Tamil children [84%] follow Hinduism). Nearly a half of all pupils (62/125; 49.6%) had a pet in their family (Table 1).

Sample characteristics of the pupils that participated in the study in Nuwara Eliya District, Sri Lanka

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Gender: male | 34 | 47 | 30 | 58 | 64 | 51.2 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhist | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Hindu | 22 | 30 | 27 | 52 | 49 | 39.2 |

| Other | 14 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 14.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Sinhalese | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Tamil | 29 | 40 | 26 | 50 | 55 | 44.0 |

| Other | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 9.6 |

| Owned a dog | 36 | 49 | 26 | 50 | 62 | 49.6 |

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Gender: male | 34 | 47 | 30 | 58 | 64 | 51.2 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhist | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Hindu | 22 | 30 | 27 | 52 | 49 | 39.2 |

| Other | 14 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 14.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Sinhalese | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Tamil | 29 | 40 | 26 | 50 | 55 | 44.0 |

| Other | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 9.6 |

| Owned a dog | 36 | 49 | 26 | 50 | 62 | 49.6 |

Sample characteristics of the pupils that participated in the study in Nuwara Eliya District, Sri Lanka

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Gender: male | 34 | 47 | 30 | 58 | 64 | 51.2 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhist | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Hindu | 22 | 30 | 27 | 52 | 49 | 39.2 |

| Other | 14 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 14.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Sinhalese | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Tamil | 29 | 40 | 26 | 50 | 55 | 44.0 |

| Other | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 9.6 |

| Owned a dog | 36 | 49 | 26 | 50 | 62 | 49.6 |

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Gender: male | 34 | 47 | 30 | 58 | 64 | 51.2 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhist | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Hindu | 22 | 30 | 27 | 52 | 49 | 39.2 |

| Other | 14 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 14.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Sinhalese | 37 | 51 | 21 | 40 | 58 | 46.4 |

| Tamil | 29 | 40 | 26 | 50 | 55 | 44.0 |

| Other | 7 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 9.6 |

| Owned a dog | 36 | 49 | 26 | 50 | 62 | 49.6 |

Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of rabies (pre-test)

The level of rabies KAP among the pupils depended on their responses. More than half of the pupils understood that people scratched or bitten by an animal should clean the wound right away (77/125; 61.6%). Approximately half of them (64/125; 51.2%) knew that those infected with rabies will almost always die, and that people get rabies from bites from an infected animal. However, pupils were less likely to inform an adult as an immediate action after animal exposure from scratches or bites (20/125; 16.0%). Among the reservoirs of rabid virus, dogs were the most common animals carrying rabies (93/125; 74.4%), followed by cats (73/125; 58.4%) and bats (42/125; 33.6%). Nearly half of the pupils (59/125; 47.2%) identified snakes as a non-rabies carrier, but about the same number of pupils (58/125; 46.4%) also believed the snakes could transmit the virus. Overall, we obtained 41.7% of correct responses. There were no significant statistical score differences between the study and control groups (39.6% vs 44.5%; t=1.57; df=124; p=0.118) (Table 2).

Comparison of knowledge of rabies among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka between pre- and post-tests

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | ||||

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| If a person or animal gets rabies, they will almost always die: true | 36 | 49 | 49 | 67 | 28 | 54 | 30 | 58 |

| How do you get rabies? bite from an infected animal | 34 | 47 | 49 | 67 | 30 | 58 | 27 | 52 |

| The first thing to do after scratched by an animal: tell an adult | 12 | 16 | 45 | 62 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| Rabies is caused by a virus: true | 21 | 29 | 51 | 70 | 18 | 35 | 18 | 35 |

| A snake bite can give you rabies: false | 32 | 44 | 50 | 69 | 17 | 33 | 27 | 52 |

| If you were scratched by an animal, you should clean the wound right away: true | 44 | 60 | 54 | 74 | 33 | 64 | 39 | 75 |

| You will always know if you are bitten by a bat, even if you are asleep: false | 20 | 27 | 29 | 40 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 37 |

| How can you best protect dogs against rabies? vaccination | 19 | 26 | 45 | 62 | 17 | 33 | 26 | 50 |

| Which of these animals can carry rabies? | ||||||||

| Dogs | 56 | 77 | 62 | 85 | 37 | 71 | 41 | 79 |

| Cats | 39 | 53 | 64 | 88 | 34 | 65 | 36 | 69 |

| Bats | 20 | 27 | 62 | 85 | 22 | 42 | 36 | 69 |

| Rabbits | 11 | 15 | 59 | 81 | 16 | 31 | 27 | 52 |

| Snake (false) | 32 | 44 | 54 | 74.0 | 27 | 52 | 28 | 54 |

| Average correct response (% ± SD) | 39.6 ± 14.8 | 70.9 ± 30.0 | 44.5 ± 20.1 | 53.1 ± 25.4 | ||||

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | ||||

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| If a person or animal gets rabies, they will almost always die: true | 36 | 49 | 49 | 67 | 28 | 54 | 30 | 58 |

| How do you get rabies? bite from an infected animal | 34 | 47 | 49 | 67 | 30 | 58 | 27 | 52 |

| The first thing to do after scratched by an animal: tell an adult | 12 | 16 | 45 | 62 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| Rabies is caused by a virus: true | 21 | 29 | 51 | 70 | 18 | 35 | 18 | 35 |

| A snake bite can give you rabies: false | 32 | 44 | 50 | 69 | 17 | 33 | 27 | 52 |

| If you were scratched by an animal, you should clean the wound right away: true | 44 | 60 | 54 | 74 | 33 | 64 | 39 | 75 |

| You will always know if you are bitten by a bat, even if you are asleep: false | 20 | 27 | 29 | 40 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 37 |

| How can you best protect dogs against rabies? vaccination | 19 | 26 | 45 | 62 | 17 | 33 | 26 | 50 |

| Which of these animals can carry rabies? | ||||||||

| Dogs | 56 | 77 | 62 | 85 | 37 | 71 | 41 | 79 |

| Cats | 39 | 53 | 64 | 88 | 34 | 65 | 36 | 69 |

| Bats | 20 | 27 | 62 | 85 | 22 | 42 | 36 | 69 |

| Rabbits | 11 | 15 | 59 | 81 | 16 | 31 | 27 | 52 |

| Snake (false) | 32 | 44 | 54 | 74.0 | 27 | 52 | 28 | 54 |

| Average correct response (% ± SD) | 39.6 ± 14.8 | 70.9 ± 30.0 | 44.5 ± 20.1 | 53.1 ± 25.4 | ||||

Comparison of knowledge of rabies among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka between pre- and post-tests

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | ||||

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| If a person or animal gets rabies, they will almost always die: true | 36 | 49 | 49 | 67 | 28 | 54 | 30 | 58 |

| How do you get rabies? bite from an infected animal | 34 | 47 | 49 | 67 | 30 | 58 | 27 | 52 |

| The first thing to do after scratched by an animal: tell an adult | 12 | 16 | 45 | 62 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| Rabies is caused by a virus: true | 21 | 29 | 51 | 70 | 18 | 35 | 18 | 35 |

| A snake bite can give you rabies: false | 32 | 44 | 50 | 69 | 17 | 33 | 27 | 52 |

| If you were scratched by an animal, you should clean the wound right away: true | 44 | 60 | 54 | 74 | 33 | 64 | 39 | 75 |

| You will always know if you are bitten by a bat, even if you are asleep: false | 20 | 27 | 29 | 40 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 37 |

| How can you best protect dogs against rabies? vaccination | 19 | 26 | 45 | 62 | 17 | 33 | 26 | 50 |

| Which of these animals can carry rabies? | ||||||||

| Dogs | 56 | 77 | 62 | 85 | 37 | 71 | 41 | 79 |

| Cats | 39 | 53 | 64 | 88 | 34 | 65 | 36 | 69 |

| Bats | 20 | 27 | 62 | 85 | 22 | 42 | 36 | 69 |

| Rabbits | 11 | 15 | 59 | 81 | 16 | 31 | 27 | 52 |

| Snake (false) | 32 | 44 | 54 | 74.0 | 27 | 52 | 28 | 54 |

| Average correct response (% ± SD) | 39.6 ± 14.8 | 70.9 ± 30.0 | 44.5 ± 20.1 | 53.1 ± 25.4 | ||||

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | ||||

| . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| If a person or animal gets rabies, they will almost always die: true | 36 | 49 | 49 | 67 | 28 | 54 | 30 | 58 |

| How do you get rabies? bite from an infected animal | 34 | 47 | 49 | 67 | 30 | 58 | 27 | 52 |

| The first thing to do after scratched by an animal: tell an adult | 12 | 16 | 45 | 62 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| Rabies is caused by a virus: true | 21 | 29 | 51 | 70 | 18 | 35 | 18 | 35 |

| A snake bite can give you rabies: false | 32 | 44 | 50 | 69 | 17 | 33 | 27 | 52 |

| If you were scratched by an animal, you should clean the wound right away: true | 44 | 60 | 54 | 74 | 33 | 64 | 39 | 75 |

| You will always know if you are bitten by a bat, even if you are asleep: false | 20 | 27 | 29 | 40 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 37 |

| How can you best protect dogs against rabies? vaccination | 19 | 26 | 45 | 62 | 17 | 33 | 26 | 50 |

| Which of these animals can carry rabies? | ||||||||

| Dogs | 56 | 77 | 62 | 85 | 37 | 71 | 41 | 79 |

| Cats | 39 | 53 | 64 | 88 | 34 | 65 | 36 | 69 |

| Bats | 20 | 27 | 62 | 85 | 22 | 42 | 36 | 69 |

| Rabbits | 11 | 15 | 59 | 81 | 16 | 31 | 27 | 52 |

| Snake (false) | 32 | 44 | 54 | 74.0 | 27 | 52 | 28 | 54 |

| Average correct response (% ± SD) | 39.6 ± 14.8 | 70.9 ± 30.0 | 44.5 ± 20.1 | 53.1 ± 25.4 | ||||

No score differences were observed between the genders. Sinhala-speaking pupils were more likely to have a higher score than Tamil-speakers (50.8% vs 34.0%; t=5.96; df=117; p<0.001). Dog owners were also more knowledgeable about rabies compared to non-dog owners (46.5% vs 38.7%; t=2.63; df=118; p=0.010).

Impact of intervention

The score of rabies knowledge and attitude was significantly improved among the study and control groups after the intervention. A lecture along with a rabies awareness leaflet was much more effective in improving the pupil's knowledge compared with the leaflet only. Among the study group, more correct responses were observed in all the knowledge questions and their score improved by 30.9% on average. In contrast, score increases in the control group were limited to 8.6%. There were no significant changes in responses to five questions, including the statements such as ‘if a person or animal gets rabies, they will almost always die’ and ‘rabies is caused by a virus'. In the above five questions, 20% or more improvement was observed in the study group. More Sinhala-speaking pupils in the study group significantly improved their scores after the intervention (42.0% vs; 22.0%; t=3.64; df=65; p<0.001) (Table 3).

Comparison of knowledge score increment among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka between pre- and post-tests after intervention

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | % ± SD . | p-value . | % ± SD . | p-value . |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25.3 ± 28.8 | NS | 7.0 ± 19.1 | NS |

| Female | 33.2 ± 18.5 | 11.3 ± 18.5 | ||

| Language | ||||

| Sinhala | 42.0 ± 19.7 | <0.001 | 12.1 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Tamil | 22.0 ± 25.0 | 6.2 ± 22.8 | ||

| Dog owner | ||||

| Yes | 31.8 ± 23.0 | NS | 8.6 ± 20.7 | NS |

| No | 31.3 ± 22.0 | 7.7 ± 18.8 | ||

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | % ± SD . | p-value . | % ± SD . | p-value . |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25.3 ± 28.8 | NS | 7.0 ± 19.1 | NS |

| Female | 33.2 ± 18.5 | 11.3 ± 18.5 | ||

| Language | ||||

| Sinhala | 42.0 ± 19.7 | <0.001 | 12.1 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Tamil | 22.0 ± 25.0 | 6.2 ± 22.8 | ||

| Dog owner | ||||

| Yes | 31.8 ± 23.0 | NS | 8.6 ± 20.7 | NS |

| No | 31.3 ± 22.0 | 7.7 ± 18.8 | ||

NS: not significant.

Comparison of knowledge score increment among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka between pre- and post-tests after intervention

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | % ± SD . | p-value . | % ± SD . | p-value . |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25.3 ± 28.8 | NS | 7.0 ± 19.1 | NS |

| Female | 33.2 ± 18.5 | 11.3 ± 18.5 | ||

| Language | ||||

| Sinhala | 42.0 ± 19.7 | <0.001 | 12.1 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Tamil | 22.0 ± 25.0 | 6.2 ± 22.8 | ||

| Dog owner | ||||

| Yes | 31.8 ± 23.0 | NS | 8.6 ± 20.7 | NS |

| No | 31.3 ± 22.0 | 7.7 ± 18.8 | ||

| . | Study group (n = 73) . | Control group (n = 52) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | % ± SD . | p-value . | % ± SD . | p-value . |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25.3 ± 28.8 | NS | 7.0 ± 19.1 | NS |

| Female | 33.2 ± 18.5 | 11.3 ± 18.5 | ||

| Language | ||||

| Sinhala | 42.0 ± 19.7 | <0.001 | 12.1 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Tamil | 22.0 ± 25.0 | 6.2 ± 22.8 | ||

| Dog owner | ||||

| Yes | 31.8 ± 23.0 | NS | 8.6 ± 20.7 | NS |

| No | 31.3 ± 22.0 | 7.7 ± 18.8 | ||

NS: not significant.

A multiple linear regression analysis indicated that the type of intervention as well as ethnicity was significantly associated with the score increment. Sinhala-speaking pupils and those in the study group significantly improved their knowledge after the intervention (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Multiple linear regression for the relationship between the test score increment and the variables of interests among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka

| Variable (reference group) . | Coefficient . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 3.638 | NS |

| Language (Tamil) | 13.458 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (control) | 19.396 | <0.001 |

| Dog owner (no) | -1.463 | NS |

| Variable (reference group) . | Coefficient . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 3.638 | NS |

| Language (Tamil) | 13.458 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (control) | 19.396 | <0.001 |

| Dog owner (no) | -1.463 | NS |

NS: not significant.

Multiple linear regression for the relationship between the test score increment and the variables of interests among school pupils in rural Sri Lanka

| Variable (reference group) . | Coefficient . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 3.638 | NS |

| Language (Tamil) | 13.458 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (control) | 19.396 | <0.001 |

| Dog owner (no) | -1.463 | NS |

| Variable (reference group) . | Coefficient . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 3.638 | NS |

| Language (Tamil) | 13.458 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (control) | 19.396 | <0.001 |

| Dog owner (no) | -1.463 | NS |

NS: not significant.

Discussion

We conducted a pilot rabies awareness-raising programme among school children in Sri Lanka, called Rabies Edutainment 4 Kids. The purpose of the programme was to improve practices on rabies prevention and pet care among children in a resource-limited setting. Our results indicate that this programme successfully increased the pupil's awareness of rabies in a short period of time, and school teachers played a key role in disseminating the message of rabies prevention to their pupils as part of the school curricula.

Because 80% of the population in Sri Lanka resides in rural areas, it is necessary to promote the empowerment of local communities and their active participation in community-based events in order to successfully implement rabies prevention programmes. In our programme, teachers were in charge of conducting both a pre- and post-test of rabies KAP in the class, distributing the awareness leaflet or providing a lecture, and supervising a poster and photo capture event. Pupils in the study group who attended the lecture on rabies prevention and participated in the activities improved their knowledge and awareness. This approach proved effective in that active learning through play promoted pupils to comprehend the meaning of rabies prevention and its related messages, which may significantly decrease the chance of dog bites and rabies cases.17

It also enabled the schools or the education ministry to send a positive message to parents and the community that schools were willing to protect pupils from preventable diseases as a part of the school curricula and were teaching pupils the necessary life skills. The programme was successful because the teachers were able to understand the importance of the protection of their pupils from rabies and were able to educate them during this programme. Taking into account the low cost and time of the programme implementation, this training procedure would be feasible and practical in other resource-limited settings, such as rural communities in Sri Lanka and the rest of rabies-endemic countries.

However, in order to maximise the effect of the intervention, particularly in the Sri Lankan settings, it is essential to take into account the socio-cultural diversity of the population, where ethnicity is a strong indicator of understanding public health matters. Successful control programmes are often location-specific and need substantial adjustments in order to replicate the programme in other areas with community participation.14 Though no such evidence on rabies preventive practices is available thus far in Sri Lanka, a previous study on HIV/AIDS prevention indicated that participants from a Buddhist background, who are approximately 70% of the population, generally had a better understanding of health-related issues such as the mode of transmission of disease and preventive methods than other groups.18 Our study also found that Sinhala-speaking pupils, many of whom follow Buddhism, had more knowledge on the issue of rabies control at the beginning of the study and they significantly developed their knowledge and attitude through the programme, regardless of intervention. Although we cannot categorise the pupils' ethnic diversity into two mother languages in our regression analysis due to the limited sample size, we can determine that more information and human resources were available for majorities. In other words, the minority groups may have limited access to essential items and materials for health education. In particular, our targeted Tamil schools were located in typical rural areas of tea plantations in mountainous localities far from the center of the town; where families live under the poverty line and are more poorly educated. These scenarios make it difficult to implement the appropriate interventions to improve awareness and knowledge on health-related issues and to promote attitude changes to disease prevention. Although our study was not primarily intended to compare the outcomes by religious/ethnic background or primary language spoken, various socio-cultural differences including religious or ethnic groups, languages, customs, educational attainment and/or the level of poverty should be considered when trying to implement future educational campaigns in school curricula.

This study had some limitations. Due to the limited number of participants, beneficiaries from this edutainment programme were limited to pupils and their school teachers. Also, our sample itself does not reflect the ethnic distribution of the district. However, the above campaign proved to be effective in improving the pupils' knowledge of rabies and it is recommended that similar programmes and activities be expanded to different areas of the nation. As rabies deaths are more likely to occur in areas of high population density such as Colombo and Gampaha districts,7,19 this kind of community activities should be expanded to more urban, crowded rabies-endemic areas accordingly.

Conclusions

The threat of rabies to pupils in Sri Lanka would be reduced if they are given the appropriate education as a part of the school curricula. This pilot programme was relatively cost-effective and school teachers felt no added burden to teach a special class on rabies. Close collaboration with a local educational office is key to the successful implementation of a school-based rabies control programme.

Authors' contributions: KK, AJ, GSPdeSG and HT conceived the study; KK, YO, AJ, GSPdeSG and HT designed the study protocol; KK, YO, AJ, NYD and NGWP carried out the field study, analysis and interpretation of the data; KK drafted the manuscript; CDG, AA and HT critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. HT is the guarantor of the paper.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the Hokkaido University Global COE Programme for the 'Establishment of International Collaboration Centers for Zoonosis Control‘, Japan; Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka; Department of Health Services, Central Province, Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition, Sri Lanka and Hanguranketa Zonal Educational Office, Ministry of Education, Sri Lanka.

Funding: This work was supported by the Hokkaido University Global COE Programme on ‘Establishment of International Collaboration Centers for Zoonosis Control’.

Competing interest: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the ethical review committee at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka [2009/EC/02].

Comments