-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura M. Koehly, It’s Interpersonal: Family Relationships, Genetic Risk, and Caregiving, The Gerontologist, Volume 57, Issue 1, 1 February 2017, Pages 32–39, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

My research program considers family relationships across the life course: in early life, with a focus on disease prevention—leveraging genetic risk information and relationships to motivate health-promoting behaviors—and in later life, with a focus on informal caregiving—identifying characteristics of those most vulnerable to, or resilient from, caregiver stress. It is fortuitous, if not tragic, then, that my research and personal worlds collided during my mother’s final 8 months of life. Here, I discuss how this experience has shifted my thinking within both arms of my research program. First, I consider the state of the science in family health history, arguing that the current approach which focuses on an individual’s first- and second-degree relatives does not take us far enough into the relational landscape to activate communal coping with disease risk. Second, I discuss caregiving from a family systems perspective. My family’s experience confirmed the importance of using a systems approach and highlighted a need to identify underlying variability in members’ expectations of caregiving roles. In so doing, I capture the significance of understanding the multiple perspectives that frame a context in which families adapt and cope with risk and disease diagnoses.

Interdependence, the notion that individual lives are inherently linked, begins prior to birth and extends throughout the life course (Elder, 1994). As we age, we begin to take on multiple, varying social roles with those most salient often being our family roles—that of child, sibling, and parent. It is through such roles that our lives become interwoven, often taking on multiple social trajectories in synchrony (Elder, 1994). By social trajectory, I mean that we create meaning through our social experience (Cottone, 2011), and such meaning influences our decisions when we encounter different transition points in our lives, thereby affecting our future. This is what happened during my family’s experience with my mother’s cancer diagnosis and her subsequent death, in which we found ourselves considering each of our many family and social roles and how they intersected with both our newly realized inherited disease risk and caregiving responsibilities. As I was enmeshed in these events—and as I reflect on them almost 2 years later—I am struck by how this experience affected and forever changed our family and the interpersonal processes that characterize how we interact, communicate with, and support each other. Although being very personal, the experience was also very “interpersonal.” Moreover, this experience directly overlapped with my programmatic work, providing an opportunity for me to gain a greater understanding of the factors that influence how families cope with genetic risk and negotiate the responsibilities of caring for a chronically ill-loved one.

In the current paper, I describe, from my perspective, how my mother’s illness affected the interpersonal landscape of the family system, thereby moving my family along two new social trajectories—one focused on increasing our knowledge about family risk and supporting health-promoting behaviors and the other aimed at providing care for my mother during her treatment and end-of-life transition. I extend this notion beyond that of personal social trajectories (Elder, 1994), that is, those who are individual- or ego-centric, to consider the social trajectories of a collective, that is, those who are group- or family-centric. Although my mother’s illness affected me personally (and professionally), it also influenced the social functioning—and social trajectory—of my family. Thus, the personal is embedded within the collective—a point that is not often integrated into our scientific enterprise but is highly relevant when considering the reciprocal influences of family members across different, yet synchronous, trajectories during troubled times (Conger & Elder, 1994).

Background

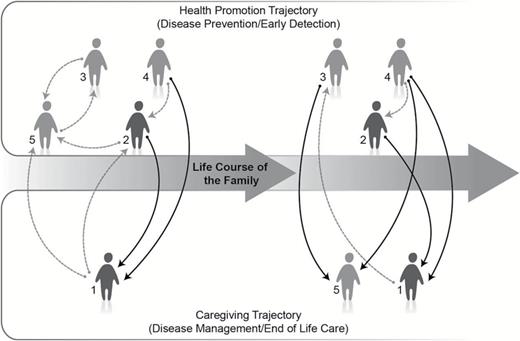

My research program aims to understand the interpersonal context that surrounds families as they communicate about and adapt to inherited disease risk, with a larger goal of identifying points of intervention within the family environment to facilitate adaptation. I consider this coping process at two junctures in the illness career each reflecting a different social trajectory (see Figure 1). For example, members who are unaffected by, but at risk, for the condition (i.e., those above the arrow in the Health Promotion Trajectory) may receive resources from other family members aimed at primary or secondary prevention efforts. Such resources may include, for example, support and encouragement to engage in risk-reducing behaviors or clinical screening related to early detection. However, members who are affected by the condition (i.e., those below the arrow in the Caregiving Trajectory) may require different types of support related to disease management, treatment course, or end-of-life care. Over time, the composition, function, and structure of the system evolve in order to accommodate family members’ shifting needs—those at risk may ultimately develop the condition and, thus, require adjustments to needed support resources.

Illustration of two, synchronous, social trajectories resulting from inherited disease diagnosis. In the Health Promotion Trajectory, family members support and encourage behaviors aimed at disease prevention and early detection in those unaffected but at risk. In the Caregiving Trajectory, family members support caregiving activities related to disease management of end-of-life care for those diagnosed with the condition. Symbols represent family members (black = older generation; gray = younger generation). The lines connecting family members represent provision of social resources (black = caregiving activities; gray = support toward risk-reducing or early detection behaviors). Over time, those who were previously at risk may become affected by the condition and transition from the Health Promotion Trajectory to the Caregiving Trajectory, as illustrated by family member no. 5.

Family Systems as Social Resources

Families develop established patterns of interaction and resource exchange over time, and these patterns lend themselves to the formation of expectations about who will, and who will not, provide resources when needed. Often the provision or receipt of social resources is aligned with particular social roles (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987). Moreover, the function and structure of these relationships change with the passage of time due to evolving experiences and life stages (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987; Caspi & Roberts, 2001). As parents age, they may require more instrumental support. In turn, this need for more instrumental support can significantly affect the relationship quality between parents and their children, particularly for children involved in care (Kim et al., 2016). Similarly, in the context of some inherited conditions, when a new generation is born into the family or new disease diagnoses emerge, families continue to traverse these two social trajectories with resource exchanges focused on preventing disease in the youngest generation and supporting disease management in those newly diagnosed.

The family system is a salient social context comprised of a collection of social resources that can be leveraged as coping resources (Lowenstein & Daatland, 2006). Coping can be problem focused, or active in nature, where we problem solve or actively alter the source of stress (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989); interpersonal support might be sought for instrumental reasons with the goal of actively coping with a given stressor (Carver et al., 1989; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). Family members can also offer support resources to facilitate emotion-focused coping aimed at reducing the psychological distress associated with a given stressor (Antonucci, 1990; Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Lazarus, 1998). The structure of such exchanges can identify points of influence often represented by an intergenerational transfer of support (Marcum & Koehly, 2015). For example, family health history (FHH) information might tend to flow from older generations to younger generations. Caregiving activities centered on older family members may involve coordinated efforts among the elder’s adult children with younger generations standing in when needed (Brody, 2010). In such contexts, resources may be moving upward to care for an elderly parent (or grandparent), as well as laterally among the caregivers (or siblings) within the same generation (Antonucci, Fuhrer, & Jackson, 1990; George, 1986).

Communal Coping

Communal coping is a stress and coping model grounded in interdependence theory (Lewis et al., 2006); interdependence theory recognizes that individual responses are influenced by others’ actions. Negative interdependence can occur when others’ actions are obstructive in goal attainment. Alternatively, interpersonal influence can be positive, such that patterns of interaction and resource exchange can promote goal attainment (Johnson & Johnson, 2005). Communal coping reflects positive interdependence, which can be particularly powerful when goals are shared among members of a given social group, such as the family. Communal coping is characterized by three interpersonal processes: communication about a common stressor, shared appraisals of the stressor, and cooperative strategies aimed at reducing the negative impact of the stressor (Lewis et al., 2006; Lyons, Mickelson, Sullivan, & Coyne, 1998). These cooperative strategies align with social support resources—including, for example, information, encouragement, and emotional support—which can be tailored toward problem-focused or emotion-focused coping.

Communal coping may be particularly applicable to understanding how families adapt to inherited disease risk and diagnoses (Koehly & McBride, 2010). In families affected by Mendelian cancer syndromes, identified mutations and a strong inheritance pattern from their FHHs are associated with family members’ increased disease risk. Family members in these families develop shared beliefs about risk based on both genetic test results and a shared FHH (Koehly et al., 2008; Palmquist et al., 2010). Although risk may confer through biological ties, family members not at risk (i.e., a parent, family through marriage, adopted, and fictive kin) still play important roles in communal coping processes providing informational, emotional, and instrumental support resources to both those at risk and those affected by the condition (Koehly et al., 2003). Inherited disease risk can be transformative—shifting motivation within the family toward preventive health behaviors or encouraging behaviors aimed at early detection (Ersig, Williams, Hadley, & Koehly, 2009). Moreover, families affected by inherited conditions often experience members’ journeys with the condition that they themselves may face in the future. Some may be directly involved in caring for their affected relatives; others may be mere observers (Lowit & van Teijlingen, 2005). In all, this journey creates a shared experience among family members and provides meaning to the condition, which in turn can impact decisions that shift both personal and family-level social trajectories (Palmquist et al., 2010). However, there are potential obstacles to activating communal coping processes in families affected by inherited disease—most notably barriers to genetic risk communication related both to interpersonal relationship quality and individual coping strategies (Koehly et al., 2009; Lowit & van Teijlingen, 2005; MacDonald et al., 2007).

In the context of health and illness, both genetic risk and support functions are embedded within families (Rolland & Williams, 2005). This is particularly relevant to my experience and an important consideration in the study of families affected by inherited conditions. In such contexts, as family members are negotiating their roles and expectations in supporting disease management or end-of-life care to an affected relative, they are also potentially witnessing their own future and the future of their loved ones—representing distinct, yet intertwined, social trajectories (Elder, 1994). In each, there are separate, yet related, stressors that can result in communal coping responses. However, these stressors also provide opportunities for negative interdependence processes to unfold (Harris, 1998; Ingersoll-Dayton, Neal, Ha, & Hammer, 2003; Lashewicz, Manning, Hall, & Keating, 2007). Given the limited literature investigating how families cope collectively with these stressors, my personal experience has highlighted the need to investigate the interdependence processes underlying family members’ navigation of each of these distinct social trajectories and how interpersonal responses within one trajectory may potentially impact responses in the other.

It’s Interpersonal

My research and personal worlds collided during my mother’s final 8 months of life, when she was diagnosed and underwent treatment for a rare cancer. As I began to investigate my mother’s FHH, it became clear that she was affected by a familial form of cancer that confers increased risk to me, my siblings, and their children—my family was now coping with inherited disease risk. At the same time, we were negotiating our caregiving roles, each of us forming different expectations of our own and others’ involvement in caregiving activities.

Coping With Family Risk

Although my programmatic work uses FHH-based risk information to activate communal coping processes in an effort to improve family health, I was struck by my own “ego-centeredness” in FHH knowledge when my mother became ill. Current standards for FHH risk assessment recommend collection of a three-generation pedigree, inclusive of first- and second-degree relatives (Wattendorf & Hadley, 2005). I was knowledgeable about disease diagnoses of my grandparents, aunts, uncle, parents, and siblings for several common, complex conditions that confer increased risk due to FHH. I had the three-generation pedigree down—when it was centered on me.

However, when my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I became curious about her three-generation pedigree. I knew that my aunt, her sister, had been diagnosed with two different primary cancers (colorectal and liver) with the last diagnosis claiming her life, and I knew that my maternal grandmother had died at an early age from breast cancer. Given that these three cancers were initiated in different sites and these relatives were second-degree relatives, the textbooks would suggest no increased cancer risk to me. However, her first-degree relatives conferred increased risk to my mother. I began to actively seek out information regarding the health history of my mother’s extended family—calling her surviving sister (my aunt) for information. This call generated an extended conversation with my aunt—who, in turn, called her cousin—in an effort to accurately capture our FHH. What we found was surprising.

My mother had a large extended family. Two of her maternal aunts had been diagnosed with cancer. She also had a handful of cousins who died from breast, ovarian, or colorectal cancer. As my mother’s last surviving cousin said quite succinctly, “We have a lot of cancer in our family.” This constellation of disease was indicative of a strong cancer risk for my mother and potentially pointed to an inherited cancer susceptibility syndrome. Indeed, after speaking to genetic counselors, my mother was strongly encouraged to pursue genetic services; each identified several candidate genes associated with inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes as possible genetic explanations for her FHH—information that would have significant implications for my own risk, that of my siblings, and my nieces and nephews. Sadly, my mother’s health declined rapidly, and we were never able to move forward with testing.

From this experience, I realized that I did not go far enough in knowing my family’s FHH. I had taken a very individualistic perspective in my assessment. Although I had a unique understanding that such information was important for my own and my siblings’ risk, I had not even considered the implications to my mother’s risk. Knowledge of my mothers’ FHH—which would have extended mine to a four-generation pedigree—may have resulted in conversations of genetic services earlier, when she was younger and healthier. My mother’s cancer diagnosis did activate communal coping along the health-promotion trajectory. The realization that her disease may have a likely genetic basis has transitioned my family to identify as a “cancer family”—one in which we take on distinct social roles with respect to gathering and disseminating family risk information, encouraging screening behaviors, and supporting emotionally the distress and worry that can accompany screening (Koehly et al., 2009).

Coping With Caregiving Burden

Concomitant with the realization that my mother’s condition might have genetic etiology conferring increased risk to family members, we were also negotiating caregiving roles in helping with my mother’s treatment course and, ultimately, end-of-life experiences. Thus began my family’s caregiver career (Pearlin, 1992). This was a family-level negotiation, as each of us had the opportunity to be involved in care provision in terms of direct care to my mother, decisions about care, as well as support and care of those providing direct care (Koehly, Ashida, Schafer, & Ludden, 2015).

Based on definitions in the literature, my father would have been considered the primary caregiver for my mother during her illness (National Alliance for Caregiving in Collaboration With AARP, 2009). My mother required significant direct care—which my father provided on a daily basis until he was unable. It was a gift to watch my father care for my mother at this time—he was incredibly gentle and patient with her. I gained new understanding of him and his role as husband and caregiver. However, my father was struggling with his own physical limitations and needed help with caregiving activities, necessitating my three siblings and I to step up to the plate. At the same time, I was researching her cancer diagnosis: primary peritoneal carcinosarcoma. My mother’s prognosis was poor with the majority of patients affected by this type of cancer surviving at most 14 months following diagnosis (Ko et al., 2005). Thus, we were also coping with the likelihood that this was the final year of my mother’s life.

Each of us began to develop different expectations of our own and others’ caregiving roles, and such expectations evolved through the lens of unique life experiences (Silverstein, Conroy, & Gans, 2008). Although we shared a common upbringing, these unique experiences played a significant role in the family dynamics that unfolded during my mother’s diagnosis, treatment, and end-of-life care. Suffice it to say that our expectations did not align, and as such, this misalignment resulted in considerable interpersonal tensions among my siblings as well as misunderstandings between my parents and their children.

For myself, I was determined to maximize my time with my mother. My career had taken me from the west coast where my parents lived to the east coast, and I had missed a lot of family-related events. In my “missing” of this, I felt very strongly that I needed to be there for her as much as possible. I was determined to be with my parents through at least half of her chemotherapy sessions that translated into a week a month. I cherish each moment that I had with my parents during this time; I grew both personally and professionally (Cohen, Colantonio, & Vernich, 2002). I brought to this experience a knowledge base from my research that allowed me to understand that active coping would likely help me in my long-term adaptation. As my department head poignantly told me—“there are no do-overs here”—so I approached my own caregiving role with a future orientation such that I did my best to address my mother’s needs, while also positioning myself in the best way for positive adaptation.

With regard to my personal expectations for my siblings’ roles, I expected my brother, who lived overseas, to plan for an extended visit with my mother. I expected my two sisters to be involved and engaged in my mother’s care, given that they were both geographically close. My brother met my expectations, bringing his family over for a month-long extended visit. The expectations I had for my sisters were regrettably not met, and this affected my own role in my mother’s care. At the time, this was incredibly distressing as I was planning to rely on my sisters to keep me informed of my mother’s response to treatment and her needs. So, I adjusted my approach by increasing my check-ins with my mother and took on the role of family disseminator, providing updates to my siblings as often as possible regarding my mother’s response to treatment.

My parents also had their own set of expectations that were in some cases met and in other cases not met—of the latter, most notably my sisters’ disengagement in my mother’s situation. So, to compensate in my role as intermediary, I tried to pepper my updates with encouragement and advice on ways my sisters could be more involved—“mom and dad would like some homemade meals, can you make something and take it over?,” “you make mom laugh so much, can you call more frequently?,” and “mom would really like to spend some time with you—can you drive up for the weekend?” These requests were largely unanswered, leading me to disengage from this encouragement process (Wackerbarth, 1999).

The (non)responsiveness of my siblings strained our previously close relationships. However, upon reflection, I recognize that each likely had their reasons and these reasons may have limited their ability to marshal the necessary psychological resources to be directly involved in caregiving. One of my sisters had been the primary caregiver for her spouse during his short fight with esophageal cancer. For her, watching my mother go through a similar fight was emotionally difficult, bringing back memories of her previous experience. Avoidance was her way of coping. Her personal history, outside of the experience of our nuclear family, significantly affected her role in the caregiving process. Similarly, my other sister was in denial about my mother’s condition. Spending time with my mother would directly challenge this coping strategy. Thus, she actively avoided any interaction with my mother and discussions about my mother’s condition that would bring her face-to-face with my mother’s situation. Each brought to the caregiving process different life experiences and individual differences in coping strategies that shaped my family’s response to caregiving demands (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 2003).

The process of negotiating caregiving roles and expectations, which continued over the course of my mother’s illness, confirmed for me the importance of research that considers the caregiving career from a family systems approach, capturing the multiple perspectives of those involved in the experience—whether they are directly involved in care provision and decisions about care, or not. What I mean by family systems approach is the inclusion of multiple family members in our scientific inquiries to gain understanding of the various perspectives and viewpoints that come to the fore as families negotiate caregiving roles and expectations (Koehly et al., 2015). Although the current account is based on my personal experience, perceptions, and critical reflection, it is just one version of my family’s experience. My siblings have read this account and offered corroboration for my primary conclusions. However, each has his/her own perception of the experience. For example, my brother expressed frustration that my sisters, who were nearby, were not involved in care provision—something that he so wanted to do but could not due to his geographical distance. My sister felt that she had tacit permission to limit her involvement, given her previous experience caring for a loved one affected by cancer. The inclusion of these multiple perspectives not only captures variability in how family members respond to such difficult situations but also can identify underlying reasons for members’ caregiving roles and expectations, factors that influence developing tensions due to unmet expectations, and, perhaps, effective strategies to help families cope with their caregiving roles.

Lessons Learned

Informing Research and Practice

My experience was grounded within a particular cultural and family context that may not translate to that of other families. Regardless, it has provided insights into how I might shift my programmatic work as it relates to two social trajectories: (a) disease prevention and early detection in at-risk family members and (b) support in disease management and care of those affected by chronic illness. In the former, there is a need to identify effective approaches that shift the frame of reference for risk beyond an individual, to the family, with the goal of activating communal coping strategies. In the latter, there is a need to utilize multi-informant designs that capture the unique personal histories and individual differences in coping strategies and their potential impact on communal coping responses to a family member’s illness and caregiving roles. Finally, particularly in the context of inherited conditions, families can find themselves traversing these intertwined social trajectories, simultaneously which can generate both positive and negative interdependencies. A large number of families are affected in some way by inherited conditions—whether common, complex conditions, such as type 2 diabetes (affecting 1 in 10 U.S. adults), autosomal recessive disorders, such as hereditary hemochromatosis or sickle cell disease (affecting 1 in 200–400 people of Northern European ancestry and 1 in 365 people of African heritage, respectively), or dominantly inherited conditions, such as Lynch syndrome (affecting 1 in 440 people; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Chen et al., 2006; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2015; Whittington, 2002). Thus, effective interventions that help at-risk families successfully adapt to their inherited disease risk and care for those affected can have far-reaching impact.

My mother’s diagnosis, and our family’s response, is consistent with my research in that disease diagnoses and genetic risk information can activate communal coping processes within the family. Although leveraging disease diagnoses as “teachable moments” to spur communal coping is one potential approach, nudging families into the health-promotion trajectory earlier in their life stage would have significantly more public health impact. Thus, there is a need to identify clear strategies for shifting the frame of reference from “me”—which might come more naturally—to “we.” One strategy might be to activate interpersonal protection motivations geared to younger generations (Koehly, Morris, Skapinsky, Goergen, & Ludden, 2015). If using FHH as a marker of risk, a child’s assessment would involve merging FHHs of two unrelated families (his mother and his father). It is clear from the literature that individuals have limited knowledge of their FHH—even when focused on a three-generation pedigree (Goergen et al., 2016); so, moving toward a four-generation pedigree can be challenging.

My experience highlighted the importance of engaging older generation family members in discussions about FHH. Consequently, involving grandparents in FHH assessments would encourage conversations about diseases that “run in the family” by emphasizing collective responsibility to create a social environment focused on the child’s health. Moreover, empowering older individuals to take on these roles of gathering and disseminating family health information to improve their family’s health may also increase their social engagement and provide meaning that enhances their aging experience (Ashida et al., 2011). Ultimately, the responsibility to discuss and disclose FHH information lies within the family itself. However, interventions to start such conversations may include, for example, guidance provided to parents during pediatric clinical care visits or community-based health education programs that reach and guide grandparents to act as family health historians for their grandchildren.

With regard to the caregiving trajectory, my experience underscored the notion that family members may cope differently with caregiving stress and that such individual differences in personal coping style can significantly influence the communal coping process. Indeed, there is some evidence that engagement in passive coping strategies, such as avoidance and denial, may negatively impact interpersonal functioning (Heid, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2016). Also, non-Hispanic White families—like mine—may be most vulnerable to the emotional and interpersonal toll of caregiving (Namkung, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2016). Thus, variability in cultural norms may influence family members’ expected caregiving roles and, thus, may be an important factor in activating communal coping. More research is necessary to explore how unique personal experiences and variability in coping style shapes the caregiving system and whether cultural context shifts the interpersonal landscape that unfolds. To do so, a multi-informant approach that captures the unique perspectives of multiple family members would allow for improved understanding of the complexities in how families cope collectively with caregiving stress. In turn, what is learned from this effort will inform the development of culturally tailored interventions that help family members negotiate their collective response to supporting and caring for a family member affected by chronic illness.

Family norms of caregiving may develop from observing our parents care for their parents, reflecting the intergenerational transfer of family expectations regarding caregiving roles. My siblings and I did not observe elder care activities when we were young due to geographical distance from and early mortality of our grandparents. Thus, my mother’s illness provided a novel experience for us to negotiate our respective caregiving roles and expectations. Given that children often learn from example, family experiences of caregiving may have important implications in how future generations provide care to members who are ill such that families with limited experience may be particularly vulnerable to the negative impact of caregiving.

Perhaps naively (or optimistically), my research is grounded in one grand assumption: that all family members will view “our problem” from the same perspective and agree on those cooperative strategies that would move the family toward a shared approach to positive adaptation. The tacit assumption that initiating the conversation about the stressor and subsequent strategies will easily unfold due to a disease diagnosis or receipt of information related to risk is overly simplified. In the context of prevention and early detection of such conditions, promoting communication and activating cooperative strategies in the form of interpersonal support resources can be fruitful. Indeed, in my family’s experience, my mother’s illness spurred information seeking related to our FHH, which in turn activated encouragement and support resources. However, for caregiving, communication about my mother’s condition, her treatment, and her need to have time with each of us did not naturally evolve into a shared understanding of who would be involved in care provision. Thus, encouragement and support may come more easily in a health-promotion context, but such resources may flow less easily when watching someone you love decline and die. When coping with the declining health of someone close, it may be difficult to shift from what is personally distressing to the needs of your affected relative. Perhaps helping families shift from an “ego-focus” to an “other-focus” is what is needed to successfully activate communal coping in the caregiving trajectory.

Importantly, families affected by inherited conditions are coping with these multiple stressors simultaneously—each requiring a different set of resources. Affected families may be marshalling social resources to cope with both the stress of members’ risk and the stress of members’ diagnoses in tandem. My experience illustrates that coping with such dual stressors can elicit both positive and negative interdependencies that affect family functioning. Often each of these trajectories is studied independently, without due consideration of how they may jointly impact each other. Thus, future research should consider both coping pathways and how they are interconnected. Such insights are critical to developing family-based interventions that activate shared goals and resources that move the family toward positive coping.

Informing My Family’s Future

My family’s experience with my mother’s illness has not only influenced my science but also defined a life experience that will shape how we move forward with decisions related to our own risk of cancer as well as caring for my father. With regard to risk, there is increased conversation about clinical screenings related to cancer prevention and early detection. We continue to pursue genetics education regarding our family cancer risk. My father is coping with my mother’s death—they were married over 60 years so this brings its own challenges related to basic activities of daily living and remaining embedded within his community. Notably, now he struggles with a neurodegenerative disease, and we are transitioning into a new caregiving career. This offers opportunity for us to learn from our experience of my mother’s illness—and perhaps move toward reconciliation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health (ZIAHG200395-01).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was written out of love for my family, and I would like to thank my parents, siblings, and extended family for helping me through both my mother’s illness and the reconciliation period. My ability to play a direct role in my mother’s care during her treatment and end-of-life transition was supported by my department chair, Colleen McBride, and my research team, particularly, Christopher Marcum and Andrea Goergen, who kept the research moving forward during my many absences; without their support, my brief, yet profoundly impactful, experience as a caregiver would not have been possible. I am eternally grateful for the continued guidance and education of two amazing genetic counselors, Donald Hadley and Melanie Myers, who advised me during my mother’s illness and now as my family continues to cope with our increased cancer risk. Finally, I would like to thank Christopher Marcum, Sato Ashida, Susan Persky, and Rachel Cohen and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

References

Author notes

*Address correspondence to Laura M. Koehly, Social and Behavioral Research Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, 31 Center Drive, Builing 31, Room B1B54, Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail: koehlyl@mail.nih.gov.

Decision Editor: Nicholas G. Castle, PhD