-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mackenzie Israel-Trummel, Shea Streeter, Police Abuse or Just Deserts? Deservingness Perceptions and State Violence, Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 86, Issue S1, 2022, Pages 499–522, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfac017

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Divergent public responses to police brutality incidents demonstrate that for some, police violence is an injustice that demands remediation, while for others state violence is justice served. We develop a novel survey experiment in which we randomize the race and gender of a victim of police violence, and then provide respondents with an opportunity to establish justice via compensation. We uncover small but consistent effects that financial restitution is most supported for a White female detainee and least supported for a Black female detainee, and this is largely driven by White respondents. Beyond the treatment effects, we show that Black respondents are much more likely to perceive detainees as deserving of restitution; across all treatments, Black respondents are 58 percent more likely than Whites to support a financial settlement. We further show that White respondents’ perceptions of deservingness are highly related to their perceptions of who is at fault for the beating—the detainee or the police—and whether the detainee was involved in crime. Black respondents remain likely to award a settlement even if they think the detainee was at fault and involved in crime. Our results provide further evidence that perceptions of who deserves restorative justice for state violence are entangled with race in targeted ways.

Police in the United States kill more civilians than in any other developed country, in both absolute numbers and per capita rates (Zimring 2017).1 African American men and women are far more likely to be subject to police force and violence than their White counterparts (DeGue, Fowler, and Calkins 2016; Buehler 2017; Paoline, Gau, and Terrill 2018). Police violence has sparked widespread protest in recent years, and cities have paid out billions to redress police misconduct.2 Nonetheless, even after the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement many Americans have continued to trust that the state administers violence legitimately and to those who deserve it (Gerber and Jackson 2017; Reinka and Leach 2017). It appears that, for some, police violence is an injustice that demands remediation, while for others state violence is justice served. In this paper, we investigate how race and gender categories affect beliefs about who is deserving of restorative justice via financial compensation after experiencing police violence.

We fielded an online survey experiment in which a large sample of White (n = 8,093) and Black Americans (n = 3,073) read about an incident in which police beat a detainee. The vignette features conflicting statements from the detainee and the police, and we randomly assign the detainee’s race and gender. We test how a detainee’s race-gender identity shapes support for financial restitution, and whether the effect of the detainee treatment is conditional on respondents’ race-gender categories. We also investigate how perceptions of the incident shape deservingness judgments across respondent race.

Ultimately, this article considers how both Black and White Americans form beliefs about who deserves recompense for violence from the state—an urgent question at the heart of issues related to race, justice, and politics (Wilson 2021). This work contributes to the growing interdisciplinary body of research that seeks to understand how Americans perceive and respond to incidents of police violence through a racial lens. Our findings may also illuminate reasons why millions of Americans took to the streets during the summer of 2020 to demand justice for Black lives (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel 2020), while others resisted even minor policing reforms.

Public Opinion and Policing

In the United States, police are the second most trusted public institution after the military (Jones 2020).3 Yet this fact conceals a great rift in opinion along racial lines. African Americans have long reported less confidence in the police than Whites (Tuch and Weitzer 1997; MacDonald and Stokes 2006; Peffley and Hurwitz 2010; Hutchings 2015), but this gap widened tremendously in 2020, with over three times as many Black as White Americans expressing very little or no confidence in law enforcement (Jones 2020). In addition to disapproving of the police, Black Americans are more likely to perceive disparate treatment by officers and to express anger about police violence (Hagan and Albonetti 1982; Flanagan and Vaughn 1996; Weitzer and Tuch 1999; Hutchings 2015; McGowen and Wylie 2020). Since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and Blue Lives Matter backlash, this racialized cleavage has become even more politically salient.

An emerging branch of policing opinion research moves beyond general attitudes to examine responses to policing practices. Some of this work considers how racially unequal policing practices can erode trust in police (Anoll, Epp, and Israel-Trummel 2022) and how exposure to police killings can both foster political engagement and depress it (Branton, Carey, and Martinez-Ebers 2021; Burch 2021). Other strands of work examine perceptions of specific policing tactics and scenarios, such as how armed status and race affect the perceived justifiability of a police killing (Porter, Wood, and Cohen 2021) and how Black and White respondents differ in their emotional and information-seeking responses to lethal police violence (McGowen and Wylie 2020; Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2021). Moreover, McGowen and Wylie (2020) show that Whites are more supportive of criminal charges against officers who kill other Whites than for officers who kill African Americans. However, very little research explicitly tests how the race and gender of policing targets interact to shape attitudes. Experimental work that does consider gender and race (e.g., Porter, Wood, and Cohen 2021) is unable to examine intersectional effects. Given that intersectional effects are often not the simple summation or multiplication of each identity category (Crenshaw 1989; McCall 2005; Hancock 2007; Jordan-Zachery 2007), we are likely missing how the race and gender of police targets together shape attitudes toward policing.

Many of these findings echo the foundational role of race identified throughout research on the carceral state more broadly: Black suspects are viewed as more criminal than White suspects; Black defendants are more likely to receive the death penalty; defendants with more Afrocentric features receive harsher sentences; and the disproportionate incarceration of Black people furthers support for punishment (Blair, Judd, and Chapleau 2004; Eberhardt et al. 2006; Hetey and Eberhardt 2014). In total, these studies show that the race of those targeted by the carceral state affects perceptions of blameworthiness and determinations of punishment. However, these studies have largely focused on perceptions of suspects’ and defendants’ guilt or officers’ justifiability in killing civilians. The US justice system includes a civil suit process of awarding damages “to make the plaintiff whole,” but American political behavior research has not thoroughly examined whether people who endure nonlethal violence from the state are viewed as deserving of recompense for their suffering. In the next section we discuss how the theoretical framework of deservingness provides a lens for understanding attitudes about who deserves restorative justice from the state.

A Deservingness Framework for State Violence

How might identity affect deservingness evaluations? Social psychology highlights several criteria upon which people rely to evaluate desert, including identity categories (Shaver 1985; Weiner 1995; Feather 1999; Lodewijkx, de Kwaadsteniet, and Nijstad 2005). As a normative ideal, we might believe that no one deserves violence from the state or wish for justice to be blind to race or gender. However, people are subject to bias—including when judging whether someone deserves a particular outcome—and many people perceive that the state has legitimate coercive power and administers it correctly (Gerber and Jackson 2017). Moreover, race fundamentally shapes beliefs about deservingness with respect to the redistributive side of the American state (Gilens 1999; Gilliam 1999; Krysan 2000; Hancock 2004; Goren 2008; Winter 2008; DeSante 2013), which is closely linked to its punitive functions (Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011).

Deservingness depends on the extent to which the involved parties are deemed responsible for the outcome (Feather 1999). If an outcome is outside someone’s control, then people tend not to judge them as deserving of the result. However, if people perceive that a person could have done something else to change the outcome, then they are likely to be judged deserving. Thus, perceived responsibility plays a vital role in judging who is deserving or not of social experiences. For instance, in a violent interaction with police, if observers think that the detainee could have acted differently to avoid the outcome then they are likely to blame the detainee for that outcome. Similarly, if observers think that police could have behaved differently, they will be more likely to see it as unjust and in need of action to restore justice. Race can affect perceptions of responsibility even in instances where people are clearly victims of crime or circumstance. For example, Black female rape victims are deemed more responsible for their victimization than White women, and medical students view Black patients as more responsible for their illnesses than White patients (Donovan 2007; Nazione and Silk 2013).

Perceptions of individual quality and morality also matter (Shaver 1985; Weiner 1995). At a basic level, the common calculus is that good actions and upstanding people deserve positive outcomes and that bad actions and disreputable people deserve negative outcomes. Evaluations of individual quality and the morality of actions within the context of policing rely on perceptions of “good guys” and “bad guys.” In American culture, “bad guys” are almost by definition those engaged in criminal activity (Claster 1992; Barnes 2014).

Criminality itself is racially constructed and gendered. White supremacy has long been justified through racist stereotypes of Black people—and especially Black men—as criminal and violent, and these racist stereotypes persist in American media and public opinion data (Gilliam and Iyengar 2000; Mendelberg 2001; Enns 2016). These perceptions are deeply embedded such that people consistently harbor latent associations between Blackness, criminality, and threat (Eberhardt et al. 2004; Todd, Thiem, and Neel 2016). McConnaughy (2017) shows that these violence stereotypes are dependent upon the precise race-gender combinations of subgroups. Respondents rate the violence of White men and Black women as generally equal, while viewing Black men as particularly violent and White women as especially nonviolent.

These intersectional stereotypes appear in the criminal justice system, where men of color are perceived as particularly suspicious (Epp, Maynard-Moody, and Haider-Markel 2014; Baumgartner et al. 2017; Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub 2018; Roach et al. 2020; Christiani 2021). Police are significantly less likely to search Black and Latina women than their male counterparts (Baumgartner et al. 2017; Christiani 2021). At the same time, police are significantly more likely to inflict harassment, sexual assault, and other forms of violence on women of color, and Black women in particular, than on White women (Jacobs 2017; Ritchie 2017; Fedina et al. 2018). Beyond policing, juries, judges, and the public writ large tend to perceive White women as victims even when they violate laws, while judging women of color more harshly for the same actions (Lucas 1995; Brennan and Vandenberg 2001; Nooruddin 2007; Dirks, Heldman, and Zack 2015).

Shared identity is also an important component of forming beliefs about desert. People tend to see those who are similar to them as deserving of good outcomes and less deserving of bad outcomes (Brewer 1979, 2001; Messick and Mackie 1989; Wilson 2021). Further, people tend to understand bad outcomes for ingroup members as the product of external forces while blaming similar outcomes for outgroup members on personal failures (Pettigrew 1979; Gibson 1998; Bracic 2020).

Race is a particularly strong identity for ingroup and outgroup formation, as it is one of the primary ways that Americans categorize others (Schneider 2004, p. 96; Ridgeway 2011, Chapter 1). Moreover, race has powerful force in political attitudes and behavior (Tate 1993; Dawson 1994; Hutchings and Valentino 2004; Lee 2008; Masuoka and Junn 2013; Anoll 2022). Masuoka and Junn (2013) argue that race fundamentally shapes how Americans perceive political issues based on racial positioning and the institutionalization of racial orders (Omi and Winant 1994). While Masuoka and Junn (2013) focus on immigration attitudes, racial differences in attitude formation are likely in the context of policing as well, where White and Black Americans have very different experiences and expectations. By contrast, gender is a notoriously weak identity politically (Gurin 1985; Gay and Tate 1998; Strolovitch, Wong, and Proctor 2017). Indeed, despite a great deal of popular attention to gender gaps in political behavior, there is often more similarity than difference between men’s and women’s attitudes and behavior, particularly once other factors like race, class, and religion are accounted for (Hyde 2005; Burden, Ono, and Yamada 2017; Bracic, Israel-Trummel, and Shortle 2019).

We anticipate that White respondents will perceive Black male detainees as least deserving of financial restitution and White female detainees as most deserving of financial restitution (H1). We expect White male detainees and Black female detainees to be viewed between these two extremes, but do not have precise expectations for their ordering. Among Black respondents, we are on shakier theoretical ground, but the research on shared identity suggests that Black respondents will be more likely to award settlements to Black detainees than White detainees (H2).

Experimental Design

We test our expectations using an experiment embedded in a large online survey (n = 8,093 White and n = 3,073 Black respondents) fielded by Survey Sampling International in the summer of 2017 (Anoll and Israel-Trummel 2017). SSI uses quota sampling to match population benchmarks with respect to education, gender, age, and region.4 All analyses reported in this paper are unweighted. Our sample also displays a range of ideological views among both groups (see Supplementary Material table S1).

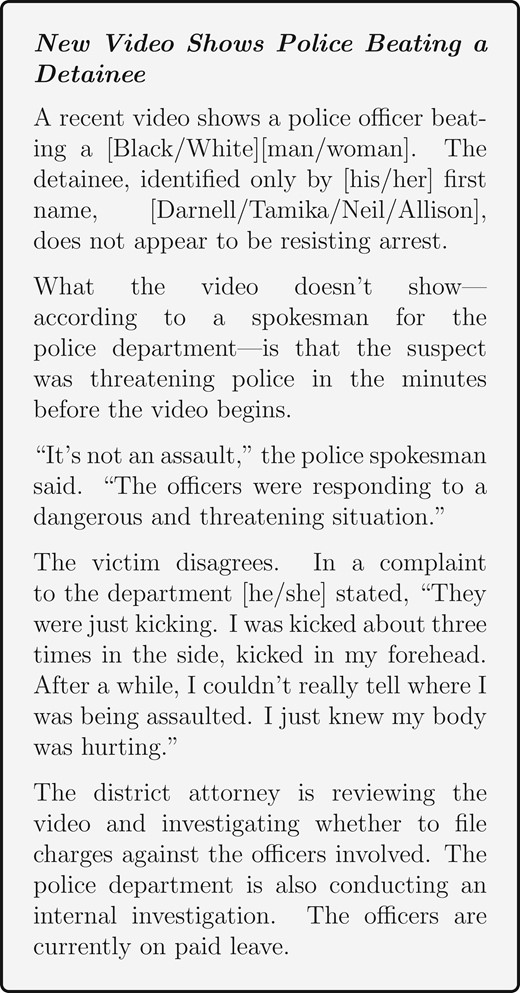

The experimental vignette mirrors narratives of violent interactions between police and citizens with its depiction of video evidence, conflicting stories of blame, and an inconclusive outcome (see figure 1). Much of the language comes from coverage of a 2016 police beating at a McDonald’s in the Bronx (Osborne 2016), and the detainee’s statement is a direct quote from the deposition of a man who sued the Baltimore Police Department after officers beat him during a 2009 traffic stop (Puente 2014). We randomize the detainee’s race (White or Black) and gender (man or woman) by stating the detainee’s race and by using gendered names with strong racial cues (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004).

This vignette is realistic as it is somewhat ambiguous, allowing respondents to form divergent views about what may have happened. It does not expressly state who was at fault or what took place before the beating. Though we anticipate that some will pay attention to the civilian’s description of their injuries, others will place more weight on the police account that the suspect threatened officers, which is commonly used as legal justification for police violence.

We measure deservingness by asking, “The detainee is bringing a suit against the city and police department for [his/her] injuries. Do you think [he/she] should receive a monetary settlement?” This outcome is binary, with 1 indicating support for financial restitution. Monetary awards in survey settings have been used to determine deservingness in a variety of contexts, including redistributive programs and following natural disasters (Iyengar and Hahn 2007; Fong and Luttmer 2009; DeSante 2013). In our study, deservingness and justice are interdependent. If an outcome is unjust, then recompense is deserved to restore justice. If an outcome is just, then no restorative justice is necessary. Americans have familiarity with assigning monetary value to the fairness of outcomes through the civil courts. Given the difficulty of disciplining, firing, or prosecuting officers (Stinson 2016), monetary damages through civil lawsuits are one of the few possible ways to seek justice for individual cases of unwarranted violence. Settlements are sometimes awarded by juries, meaning that average people can be asked to make these decisions.

Awarding a settlement is in no way guaranteed, as there are psychological motivators for believing that an outcome is just. According to just-world theory, individuals are motivated to see outcomes as just in order to preserve their belief that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get (Lerner 1980; Hafer 2000; Hafer and Gosse 2011). Similarly, for perpetrators of harm or those who identify with the perpetrators, moral disengagement can lead individuals to reinterpret the cause and effects of violence to see it as justified (Bandura et al. 1996; Bandura 2002). Because we would expect a bias toward seeing an event as just, if respondents support a financial settlement, it is a strong indication that they perceive the beating as unjust. Therefore, by providing respondents with an opportunity to administer justice in the form of support for a financial settlement for the detainee, we capture a theoretically and realistically sound measure of perceived deservingness.

To capture respondents’ broader perceptions about the incident, we asked them to judge the responsibility of the detainee and the police and to assess the criminality of the detainee. The responsibility measures asked, “Do you think the detainee could have done something differently to change the outcome of this interaction?” and “Do you think the police officers could have done something differently to change the outcome of this interaction?” Both of these responsibility variables are measured on a four-point scale (No, definitely not to Yes, definitely). The criminality measure asked respondents, “How likely do you think it is that the detainee has been involved in some sort of crime?” with answers on a four-point scale (Very unlikely to Very likely). The full wording of all other questions is provided in Supplementary Material section 2.

Average Treatment Effects

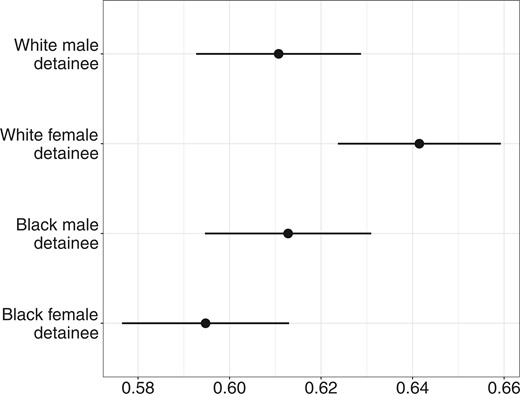

We first examine the treatment group averages for the full sample. Figure 2 shows the mean support for restoring justice via financial settlement for each treatment condition with 95 percent confidence intervals; table 1 provides all treatment means and p-values between treatments. The figure shows that White female detainees are more likely to be awarded a financial settlement than all other detainees. On average, White female detainees are between 2.8 and 4.6 percentage points more likely to be awarded a financial settlement than the White male (t = 2.382, p = 0.017), Black male (t = 2.211, p = 0.027), or Black female (t = 3.593, p = 0.000) detainees. Among the pooled respondents, there are no differences in their likelihood of awarding a settlement between the other three detainee treatment conditions. This finding confirms our intuition that the White female detainee would be perceived as most sympathetic (H1). Contrary to our expectations, however, we do not have evidence that the Black male detainee is viewed with particular suspicion, as he is not less likely to receive a financial settlement than either the White male or Black female detainees.

Proportion of respondents supporting restorative justice by treatment (full sample). Plots show the proportion supporting financial restitution via settlement for each treatment condition with 95 percent confidence intervals, pooling Black and White respondents together.

Proportion supporting restorative justice, by treatment condition (all respondents)

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| . | (n = 2,818) . | (n = 2,792) . | (n = 2,766) . | (n = 2,781) . |

| Proportion | 0.611 | 0.641 | 0.613 | 0.595 |

| p-values for test of equality of proportions for each pair of treatment conditions | ||||

| White female | 0.017 | |||

| Black male | 0.873 | 0.027 | ||

| Black female | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.170 | |

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| . | (n = 2,818) . | (n = 2,792) . | (n = 2,766) . | (n = 2,781) . |

| Proportion | 0.611 | 0.641 | 0.613 | 0.595 |

| p-values for test of equality of proportions for each pair of treatment conditions | ||||

| White female | 0.017 | |||

| Black male | 0.873 | 0.027 | ||

| Black female | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.170 | |

Note.—Number of observations per treatment are provided in parentheses; p-values are provided for comparisons between each treatment condition using two-tailed t-tests. Information on t-statistics is provided in Supplementary Material table S3.

Proportion supporting restorative justice, by treatment condition (all respondents)

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| . | (n = 2,818) . | (n = 2,792) . | (n = 2,766) . | (n = 2,781) . |

| Proportion | 0.611 | 0.641 | 0.613 | 0.595 |

| p-values for test of equality of proportions for each pair of treatment conditions | ||||

| White female | 0.017 | |||

| Black male | 0.873 | 0.027 | ||

| Black female | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.170 | |

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| . | (n = 2,818) . | (n = 2,792) . | (n = 2,766) . | (n = 2,781) . |

| Proportion | 0.611 | 0.641 | 0.613 | 0.595 |

| p-values for test of equality of proportions for each pair of treatment conditions | ||||

| White female | 0.017 | |||

| Black male | 0.873 | 0.027 | ||

| Black female | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.170 | |

Note.—Number of observations per treatment are provided in parentheses; p-values are provided for comparisons between each treatment condition using two-tailed t-tests. Information on t-statistics is provided in Supplementary Material table S3.

These results highlight the importance of intersectional analysis with respect to policing. In an analysis with only single identity categories, we would miss how White women’s gender and race identities work together such that respondents are uniquely likely to award them settlements. Clearly, beliefs about restorative justice desert depend on the race-gender identity of the victim. However, this analysis pools all respondents together, which may mask how respondents’ own identity categories condition responses to the detainee identity treatments. We turn to this in the next section by testing the treatment effects conditional on the race-gender identity category of the respondent.

Treatment Means by Race-Gender Respondent Subgroup

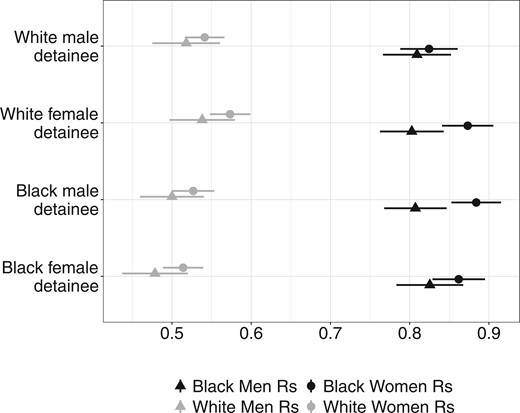

Figure 3 and table 2 provide treatment effects conditional on respondent race-gender identity category. The most immediately striking finding from figure 3 is the consistent and large respondent racial gap in perceptions of the beating incident. Pooling together respondent gender groups and collapsing the experimental treatments, two-tailed t-tests show that Whites are less likely to award a settlement to the detainee ( = 0.530 for White and = 0.838 for Black respondents, t = -35.428, p = 0.000). This gap in settlement awards means that across all treatment conditions Black respondents are 58 percent more likely than Whites to say that detainees deserve financial restitution. These patterns generally hold across treatments, as Black respondents are more likely than White respondents to award settlements even to White detainees.

Proportion supporting restorative justice by treatment and by respondent race-gender identity. Plots show the proportion supporting financial restitution via settlement for each treatment condition with 95 percent confidence intervals, separately for respondents in each race-gender subgroup.

Support for restorative justice, by treatment condition, separately for all combinations of respondent race and gender

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| White men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.518 | 0.538 | 0.500 | 0.479 |

| (n = 527) | (n = 563) | (n = 598) | (n = 560) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.506 | |||

| Black male | 0.547 | 0.193 | ||

| Black female | 0.194 | 0.046 | 0.466 | |

| White women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.541 | 0.573 | 0.527 | 0.514 |

| (n = 1539) | (n = 1439) | (n = 1374) | (n = 1486) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.078 | |||

| Black male | 0.439 | 0.013 | ||

| Black female | 0.135 | 0.001 | 0.494 | |

| Black men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.809 | 0.803 | 0.807 | 0.825 |

| (n = 325) | (n = 380) | (n = 389) | (n = 315) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.825 | |||

| Black male | 0.945 | 0.873 | ||

| Black female | 0.597 | 0.442 | 0.535 | |

| Black women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.824 | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.862 |

| (n = 427) | (n = 410) | (n = 405) | (n = 420) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.049 | |||

| Black male | 0.015 | 0.638 | ||

| Black female | 0.133 | 0.633 | 0.342 | |

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| White men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.518 | 0.538 | 0.500 | 0.479 |

| (n = 527) | (n = 563) | (n = 598) | (n = 560) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.506 | |||

| Black male | 0.547 | 0.193 | ||

| Black female | 0.194 | 0.046 | 0.466 | |

| White women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.541 | 0.573 | 0.527 | 0.514 |

| (n = 1539) | (n = 1439) | (n = 1374) | (n = 1486) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.078 | |||

| Black male | 0.439 | 0.013 | ||

| Black female | 0.135 | 0.001 | 0.494 | |

| Black men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.809 | 0.803 | 0.807 | 0.825 |

| (n = 325) | (n = 380) | (n = 389) | (n = 315) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.825 | |||

| Black male | 0.945 | 0.873 | ||

| Black female | 0.597 | 0.442 | 0.535 | |

| Black women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.824 | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.862 |

| (n = 427) | (n = 410) | (n = 405) | (n = 420) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.049 | |||

| Black male | 0.015 | 0.638 | ||

| Black female | 0.133 | 0.633 | 0.342 | |

Note.—Number of observations per treatment are provided in parentheses; p-values are provided for comparisons between each treatment condition using two-tailed t-tests. Information on t-statistics is provided in Supplementary Material table S4.

Support for restorative justice, by treatment condition, separately for all combinations of respondent race and gender

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| White men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.518 | 0.538 | 0.500 | 0.479 |

| (n = 527) | (n = 563) | (n = 598) | (n = 560) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.506 | |||

| Black male | 0.547 | 0.193 | ||

| Black female | 0.194 | 0.046 | 0.466 | |

| White women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.541 | 0.573 | 0.527 | 0.514 |

| (n = 1539) | (n = 1439) | (n = 1374) | (n = 1486) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.078 | |||

| Black male | 0.439 | 0.013 | ||

| Black female | 0.135 | 0.001 | 0.494 | |

| Black men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.809 | 0.803 | 0.807 | 0.825 |

| (n = 325) | (n = 380) | (n = 389) | (n = 315) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.825 | |||

| Black male | 0.945 | 0.873 | ||

| Black female | 0.597 | 0.442 | 0.535 | |

| Black women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.824 | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.862 |

| (n = 427) | (n = 410) | (n = 405) | (n = 420) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.049 | |||

| Black male | 0.015 | 0.638 | ||

| Black female | 0.133 | 0.633 | 0.342 | |

| . | Detainee treatment condition . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | White male . | White female . | Black male . | Black female . |

| White men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.518 | 0.538 | 0.500 | 0.479 |

| (n = 527) | (n = 563) | (n = 598) | (n = 560) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.506 | |||

| Black male | 0.547 | 0.193 | ||

| Black female | 0.194 | 0.046 | 0.466 | |

| White women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.541 | 0.573 | 0.527 | 0.514 |

| (n = 1539) | (n = 1439) | (n = 1374) | (n = 1486) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.078 | |||

| Black male | 0.439 | 0.013 | ||

| Black female | 0.135 | 0.001 | 0.494 | |

| Black men respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.809 | 0.803 | 0.807 | 0.825 |

| (n = 325) | (n = 380) | (n = 389) | (n = 315) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.825 | |||

| Black male | 0.945 | 0.873 | ||

| Black female | 0.597 | 0.442 | 0.535 | |

| Black women respondents | ||||

| Mean | 0.824 | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.862 |

| (n = 427) | (n = 410) | (n = 405) | (n = 420) | |

| p-values | ||||

| White female | 0.049 | |||

| Black male | 0.015 | 0.638 | ||

| Black female | 0.133 | 0.633 | 0.342 | |

Note.—Number of observations per treatment are provided in parentheses; p-values are provided for comparisons between each treatment condition using two-tailed t-tests. Information on t-statistics is provided in Supplementary Material table S4.

Within respondent race, smaller gender differences emerge. White men are significantly less likely than White women to support financial restitution pooling across treatment conditions ( = 0.508 for White men, = 0.539 for White women, t = -2.454, p = 0.014). Similarly, while Black men and women are both much more likely to support restorative justice than White respondents, Black women are slightly more skeptical of police than Black men. Pooling across conditions, Black women are significantly more likely than Black men to award financial restitution ( = 0.811 for Black men, = 0.860 for Black women, t = -3.705, p = 0.000).

Next, we repeat our analysis of experimental treatment effects from the prior section, but this time conditional on respondents’ race-gender identity. In the first analysis we found that the White female detainee was seen as most deserving of restitution. However, this pooled together all respondents and we anticipated in our hypotheses that respondents would react to the treatments differently conditional on their racial identity category. It is also possible that respondents’ particular race-gender category could condition their responses. Figure 3 shows very limited evidence of race-gender ingroup bias (see table 2 for means and p-values). Starting with Black men respondents, we see no discrimination in awarding settlements, as this subgroup is equally likely to award them across detainee conditions. Black women are significantly more likely to make an award to the White female and Black male detainees compared to the White male detainee, but do not perceive the Black female detainee to be more deserving of restitution than any other detainee. White men respondents are more likely to award a settlement to the White female detainee than the Black female detainee, but show no other significant differences between treatments. Finally, White women respondents are significantly more likely to award a settlement to the White female detainee compared to Black female or male detainees. White women seem to exhibit the most evidence of preference for their race-gender ingroup, but the effects remain small. This means that our findings partially support our first hypothesis that Whites perceive the White female detainee as most deserving of restitution—as White women and White men both favor her relative to at least the Black female detainee. But among White respondents, we do not see evidence of much differentiation between the other three detainees. In particular, we do not find that the Black male detainee is seen as least deserving of restitution. Our results do not support our second hypothesis, that Black respondents would support more restitution for Black detainees. Black men respondents are equally likely to award settlements across all conditions, and while Black women are more likely to award a settlement to the Black male detainee than the White male detainee, there is no difference in their awards for the Black female detainee.

In sum, then, there is little evidence that people assume the best of their race-gender ingroup. Rather, the evidence again shows that the White female detainee is perceived as most deserving among White respondents, but that White and Black respondents have very different views of the situation, with respondent gender playing a much smaller role. In Supplementary Material table S6, we further test this using an alternative strategy of modeling financial settlement support on shared race and gender identity categories. We again find little evidence to support the idea that respondents condition their evaluations on shared intersectional identity with the detainee. Detainees’ race-gender identity does elicit treatment effects, but these are quite small compared to the differences in reaction between Black and White Americans.

Understanding Support for Restoring Justice

The findings show small but significant effects of the detainee identity experimental treatments, differences across respondent race, and much smaller differences across respondent gender. These findings are not consistent with a theory of shared identity driving respondents’ support for financial restitution. Put differently, this is not a simple case of people believing that those with whom they share identity categories should receive a form of justice for experiencing police violence and those who differ from them should not. Despite Whites being most willing to award a settlement to a White female detainee, they are still quite unwilling to do so compared to Black respondents regardless of detainee identity. Rather, White and Black Americans have fundamentally different views about state violence and justice.

Three theories could account for the large racial difference in support of the restorative justice process here. The first is that differences in identification with police officers could lead Whites to resort more often to moral disengagement (Bandura et al. 1996; Bandura 2002). If Whites think of police as being like them and representing their interests, they might excuse the officers’ actions or rationalize the necessity of violence. A second explanation could stem from attitudes about government spending. Whites may simply be more likely to embrace conservative ideals about limited government spending, and consequently would be reluctant to support a settlement, even if they believed that the target was neither responsible nor engaged in criminal activity (Sniderman and Tetlock 1986). A third explanation could be racial differences in just-world beliefs (Lerner 1980). Given the long history of racial injustice within the carceral state, Black respondents may be less inclined than Whites to expect interactions with the police to be just, and consequently less likely to search for ways to justify the beating. The experiment was not designed specifically to test the mechanism through which respondents judge deservingness. However, we can probe respondents’ decision-making by examining how our measures of fault and perceived criminality are associated with awarding financial restitution, controlling for the race-gender detainee treatment and looking across race-gender respondent subgroups. These results can provide some indication as to which theoretical mechanism may prove fruitful for future research.

If identification with the police and moral disengagement were driving the disparity, we would expect less blame for police among White respondents and a higher correlation between perceptions of police culpability and support for restitution among White respondents than among Black respondents. White respondents are indeed significantly less likely to blame the police than are Black respondents ( = 2.253 for Whites and = 2.478 for Black respondents, t = -14.715, p = 0.000). If differences in restitution awards were the result of Whites’ attitudes about government spending, we would expect perceptions of blame and criminality to be more correlated with awarding a settlement among Black respondents than among Whites. This is because fiscally conservative Whites would be unwilling to support a government settlement regardless of their perceptions of the beating. If just-world beliefs explain the racial differences, we would expect White Americans to assign more blame to the detainee and view them as criminal, but would further expect both Black and White respondents’ likelihood of awarding a settlement to be associated with their perceptions of fault and criminality. White respondents are significantly more likely to believe that the detainee was at fault ( = 1.780 for White and = 1.519 for Black respondents, t = 14.102, p = 0.000) and that the detainee was engaged in criminal activity ( = 2.017 for White and = 1.662 for Black respondents, t = 22.017, p = 0.000). But are these gaps in perceptions of the incident related to support for financial restitution?

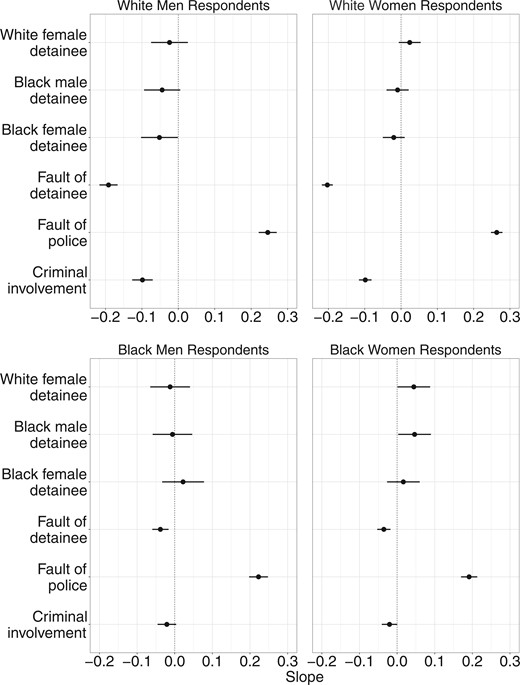

We regress awarding a settlement on perceptions of fault for the detainee and for the police, perceived criminality, and the treatment condition. We model this separately for all four race-gender subgroups and plot the coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals in figure 4. We look first at the effects of the treatments. White men are less likely to award a settlement to a detainee who is Black, regardless of gender, than to a White male detainee. By contrast, we do not see differences in the identity treatments among either White women or Black men respondents. That is, once we account for perceptions of fault and criminality, there are no differences in settlement awards by treatment condition among either White women or Black men respondents. Among Black women respondents, the White female and Black male detainees elicit more settlements than the White male detainee (as was true in the conditional treatment effect analysis), but there is again no difference between the White male and Black female conditions.

The effect of detainee identity and perceptions of beating on support for restorative justice. Plots show the slope coefficient from an OLS model predicting support for a financial settlement with 95 percent confidence intervals. These coefficient values are derived from OLS models on each race-gender subgroup of respondents separately. The models are in Supplementary Material table S5. These plots show that perceptions of fault and criminal involvement are stronger predictors of White respondents’ support for a financial settlement than for Black respondents.

Overall, these findings replicate our earlier analysis showing small identity treatment effects, but that they are not clearly a result of shared race-gender identities.5 Indeed, what this analysis shows is that more than simply the detainee’s race and gender, respondents—and especially White respondents—make their judgments about whether the detainee should receive a settlement based on their perceptions of fault and criminality. Among both White men and White women respondents, fault perceptions and criminality perceptions have large associations with support for a deservingness settlement. White men and women who hold detainees most at fault have a 0.575 and 0.609 lower probability respectively of awarding a settlement compared to those who hold detainees least responsible. The change in probability of awarding a settlement along the full range of faulting police is similar (0.736 increased probability among White men; 0.791 increased probability among White women). Among both White men and women the probability of awarding a settlement decreases by 0.295 comparing those who say the detainee wasn’t involved in crime to those who say they likely were. By contrast, among Black men and Black women, only perceptions of police fault have a comparably sized relationship to settlements, with an increase of 0.668 for Black men and 0.574 for Black women along the scale of assigning fault. Perceptions of detainee criminality and fault have much smaller effects on support for a settlement, with detainee fault perception yielding a -0.114 change in probability for Black men and a -0.106 change for Black women, and criminality perceptions even less at -0.063 for Black men and -0.061 for Black women.

These differences reflect substantially different probabilities of supporting a financial settlement across respondent race. Black respondents are simply much more likely to support a financial settlement, with 81 percent of Black men and 86 percent of Black women awarding one. Black respondents are also unlikely to reduce this support much even when they believe the detainee is at fault and was probably involved in criminal activity. By contrast, White respondents are much less likely to indicate that there is an injustice to remedy, with 50 percent of White men and 54 percent of White women awarding a financial settlement to the detainee. Most striking, holding all other values at their median, the probability of awarding a settlement when police are most blamed is 0.704 for a White man respondent and 0.730 for a White woman respondent. This remains below the average settlement award among Black respondents.

We find no support for the implications of moral disengagement or principled conservatism. Although White respondents are less likely to hold the police responsible for the beating, the 9.9 percent difference in means between Black and White respondents on this measure pales in comparison with the 58 percent difference in support for a settlement. Furthermore, blame for the police is similarly correlated with support for a settlement among Black and White respondents. This suggests that the racial difference in support for settlements is likely not driven by White respondents’ identification with the officer and consequent moral disengagement.

The three perception variables are also more highly correlated with support for a settlement among White respondents, suggesting that they are basing their support more on their perception of the beating than on ideological beliefs about government spending. Rather, the coefficients show that Black respondents are the ones whose support for the settlement is less tied to perceptions of the incident. It appears that not only do Black respondents much more strongly support financial restitution for police violence than White respondents, they are likely to do so even when they perceive the detainee to be at fault or involved in crime. This is striking because it suggests that White and Black Americans might not only have differences in just-world belief, but that Black respondents could even have an “unjust-world belief.” They appear to view the beating as unjust and undeserved—sometimes even regardless of their perceptions of the circumstances. We invite future research to investigate the mechanisms behind these disparate views of state violence and deservingness, perhaps through the lens of racialized just-world belief.

Conclusion

Public perception of police actions will help determine the future of policing. Recent scholarship shows that American political elites expanded and entrenched the carceral state in response to the preferences of a punitive populace (Enns 2014, 2016; Miller 2016). By the same token, however, perceptions that the police overstep their mandate or abuse civilians could lead to the public rolling back policing powers or resources. This means that it is of paramount importance to understand how the public views the legitimacy of state violence and the deservingness of citizens subjected to such violence. We offer a first examination of how identity shapes Americans’ views of whether violent police actions constitute just desert or an abuse that must be rectified.

Our results show that White respondents are most likely to support financial restitution for the White female detainee, and this effect is consistent across respondent gender. This finding most likely stems from ideologies of White womanhood in which protection of “women” is inextricably bound up with race (Nooruddin 2007; Junn 2017), such that Black women are deemed undeserving or are ignored (Crenshaw 1991; Hancock 2004). Though our experimental design cannot directly reveal the reasons for the difference in deservingness perception between female detainees by their race, we speculate that the “angry Black woman” stereotype—which presumes that Black women are irate, irrational, hostile, and loud-mouthed (Harris-Perry 2011)—may play a role in White respondents’ decreased willingness to provide restitution to the Black female detainee compared to the White female detainee.

Beyond the small treatment effects we uncover, our findings underscore how differently Black and White Americans perceive the police and the carceral state. Regardless of the detainee’s race-gender identity, Black respondents are significantly and substantially more likely than White respondents to say the detainee deserves restitution. Moreover, Black respondents are likely to support restitution even when they perceive detainees are at fault, whereas White respondents condition support for restitution on their perceptions of fault and criminality. This highlights the political challenge facing social movements like BLM that seek to replace American policing. In the eyes of many White Americans, police violence may not be an injustice that demands restitution but may itself be justice served.

Data Availability Statement

REPLICATION DATA AND DOCUMENTATION will be available within 12 months of publication at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DNMHCO.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL may be found in the online version of this article: https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfac017.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Mackenzie Israel-Trummel is an assistant professor in the Government Department at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. Shea Streeter is an assistant professor in the Political Science Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

The authors are grateful to Allison Anoll, Ana Bracic, Drew Engelhardt, Kate Epstein, Edgar Franco Vivanco, Vince Hutchings, Donald Kinder, Nicholas Valentino, Hannah Walker, and the participants in the 2019 APSA Criminal Justice Mini-Conference, the Duke University Racial and Ethnic Politics Seminar, and the University of Michigan Center for Political Studies Interdisciplinary Workshop on Politics and Policy for feedback and assistance on this project. The authors are particularly grateful to Maria Krysan and David Wilson for their support and guidance. They also thank the journal editors.

Footnotes

Police in the United States kill an average of three people per day (Zimring 2017). This is over four times more than in Canada and over one hundred times more than in England and Wales.

Between 2010 and 2020, 31 US cities cumulatively paid over $3 billion in police settlements (Thomson-DeVeaux, Bronner, and Sharma 2021).

In a June 8–July 24, 2020, Gallup poll, 48 percent of American adults expressed a great deal/quite a lot of confidence in the police and 72 percent expressed a great deal/quite a lot of confidence in the military.

Response rates are difficult to calculate from online opt-in panel surveys (AAPOR 2010), but SSI estimated a 74 percent participation rate from this survey. An opt-in internet panel is not able to make claims about representativeness to the US population (AAPOR 2015), but such surveys are excellent for experiments (Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz 2012).

We probe these results in a series of models in Supplementary Material tables S7–S9, where we examine the main effects of the race and gender treatments, their interaction, and include the fault perceptions and criminal involvement variables individually. In each model, we find similar small effects of the experimental treatments.

References

AAPOR.

AAPOR.