-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kuk-Kyoung Moon, Robert K Christensen, Moderating Diversity, Collective Commitment, and Discrimination: The Role of Ethical Leaders in the Public Sector, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Volume 32, Issue 2, April 2022, Pages 380–397, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muab035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite public administration’s growing interest in personnel diversity and ethical leadership, little is known about the effectiveness of ethical leadership in managing diverse public workforces. Can ethical leadership moderate the relationships between demographic diversity and key organizational outcomes? To answer, we synthesize four theories about demographic diversity, ethical leadership, and inclusion: social categorization theory, social exchange theory, social learning theory, and optimal distinctiveness theory. These theories illuminate the interrelationships between diversity, ethical leadership, and two types of collective organizational outcomes: affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination. Using panel data from the US federal government, feasible generalized least squares models indicate that racial diversity is negatively related to affective commitment climate and positively related to race-based employment discrimination. The results also show that ethical leadership beneficially moderates the associations of racial diversity with the two organizational outcomes. These findings suggest that ethical leadership aids public managers and personnel in racially diverse public agencies.

요약

공공부문에서의 인적자원 다양성과 윤리적 리더십(ethical leadership)에 대한 행정학자들의 높은 관심에도 불구하고 과연 윤리적 리더십이 효과적인 다양성 관리전략이 될 수 있는지에 관한 실증연구는 거의 이루어지지 않았다. 이에 본 연구는 사회범주화이론(social categorization theory), 사회교환이론(social exchange theory), 사회학습이론(social learning theory), 최적차별화이론(optimal distinctiveness theory) 등 다양성에 관한 여러 이론을 결합하여 미연방 정부에서의 인종 다양성(racial diversity)과 윤리적 리더십이 정서적 몰입과 조직 내 고용차별에 미치는 영향과 함께 윤리적 리더십의 조절효과를 탐색하였다. 미연방 정부 패널데이터를 분석한 결과, 인종 다양성은 조직수준의 정서적 몰입(affective commitment climate)에는 부(-)의 영향을 미치지만, 인종적 고용차별(race-based employment discrimination)에는 정(+)의 영향을 미치는 것으로 밝혀졌다. 나아가 윤리적 리더십은 인종 다양성이 조직수준의 정서적 몰입과 인종적 고용차별에 미치는 효과를 완화하는 것으로 드러났다. 이러한 분석결과를 바탕으로 공공부문에서 윤리적 리더십은 인종 다양성을 효과적으로 관리할 수 있는 전략이 될 수 있다는 정책적 시사점을 제시하였다.

The US federal workforce has become increasingly racially diverse (Choi 2011), and many scholars recognize racial diversity as a prominent issue in the practice and research of public administration (Sabharwal, Levine, and D’Agostino 2018; see Supplementary Appendix 1). Early calls (Kellough and Naff 2004; Selden and Selden 2001) and the subsequent mixed empirical evidence concerning the relationship between racial diversity and work-related outcomes have prompted researchers to better explore the management of racially diverse workforces (Pitts and Towne 2015). Many scholars have responded by researching the contextual factors—such as diversity management, task characteristics, and organizational culture—that may moderate the relationship between racial diversity and organizational outcomes (Choi 2009; Horwitz and Horwitz 2007; Moon and Christensen 2019; Roberson, Ryan, and Ragins 2017).

Although evidence on contextual moderators is mounting, scholars have paid less attention to how leadership styles condition demographic diversity–outcome relationships (Guillaume et al. 2017). In this sense, DiTomaso and Hooijberg (1996, 163) have presciently noted that “one would think that in the field of management the study of diversity would be all about leadership, but this is not what has developed.”

In this article, we explore ethical leadership as a promising candidate to understand what might help public personnel effectively work together in increasingly diverse settings. We are particularly interested in the role of ethical leadership in moderating the associations of racial diversity with (1) affective commitment climate and (2) race-based employment discrimination.

Our interest in affective commitment (defined as an employee’s emotional attachment to the organization) and racial discrimination in employment (defined as unfair and differential treatment based on an employee’s race) at the organizational level is three-fold. First, these outcomes are frequently studied together in diversity research (Triana and Garcia 2009), including their collective or aggregated forms, such as affective commitment climate (Kunze, Boehm, and Bruch 2011). Both affective commitment and employment discrimination are key to understanding job performance, turnover, and organizational citizenship behavior (Meyer et al. 2002). Second, and more importantly, affective commitment is “a relational construct indicative of social exchanges [that] plays a key role in understanding the mechanisms through which workplace incivility produces negative effects” (Taylor, Bedeian, and Kluemper 2012, 879), where discrimination claims constitute an observable measure of negative effects in the workplace. Taken together, these two outcomes—commitment and discrimination—provide a yardstick by which we and others might assess how well racially diverse personnel are interacting in public agencies. Finally, because racial diversity is an organizational-level construct, our article focuses on affective commitment climate—employees’ shared perceptions of affective commitment within the organization—and race-based employment discrimination—employees’ collective experience of racial discrimination in the organization—as consequences of racial diversity.

To better understand the interrelationships between racial diversity, ethical leadership, affective commitment climate, and race-based employment discrimination, we extend four theories—social categorization theory (SCT), social exchange theory (SET), social learning theory (SLT), and optimal distinctiveness theory (ODT). Our purpose in applying multiple theories aligns with John’s (2012) notion of “super-synthesis” that “combines the insights of a range of theories” (Cairney 2013, 4) to promote a hybrid understanding of the relationships in question.

Using panel data from the US federal subagencies, we find that racial diversity is negatively associated with self-reported affective commitment climate and positively related to observable race-based employment discrimination claims. Ethical leadership is positively related to affective commitment climate and negatively related to race-based employment discrimination. However, reflecting insights from ODT, ethical leadership significantly attenuates the negative relationship of racial diversity with affective commitment climate and the positive relationship of racial diversity with race-based employment discrimination. This article concludes by addressing the theoretical and practical implications of these results. Among others, attracting and developing ethical leadership, which is a relatively understudied but important issue in public administration, plays a pivotal role in realizing the positive organizational outcomes of a diverse workforce.

Theorizing Diversity, Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, and Discrimination

Conceptualizations of Affective Commitment Climate and Race-Based Employment Discrimination at the Organizational Level

Although scholars have explored various consequences of racial diversity, affective commitment and discrimination are often mentioned as key outcomes or key reasons to effectively manage racial diversity in the public sector workforce (Choi 2013). Meyer and Allen (1991, 62) have defined organizational commitment as “a desire, a need, and/or an obligation to maintain membership in the organization.” A stream of empirical studies has identified the three subdimensions of organizational commitment: affective, normative, and continuance. Affective commitment refers to an employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in his or her organization (Allen and Meyer 1990; Meyer and Allen 1997). Normative commitment represents internalized normative pressures for an employee to remain in the organization and meet organizational goals. Continuance commitment is defined as commitment based on an employee’s awareness of the social and economic costs of leaving the organization.

Among the three subdimensions, affective commitment has emerged as a principal topic in public administration research because scholars have recognized it as the most consistent, powerful predictor of organizational outcomes, including employee retention and organizational performance (Jung and Ritz 2014; Park and Rainey 2007). Public administration scholars have further explored the organizational factors that shape affective commitment and have found that leadership styles (Van der Voet, Kuipers, and Groeneveld 2016), job characteristics (Steijn and Leisink 2006), role ambiguity (Stazyk, Pandey, and Wright 2011), and goal ambiguity (Jung and Ritz 2014) are all contributors.

Race-based employment discrimination refers to unequal treatment of an employee on his or her race or ethnicity (Pager and Shepherd 2008). Although Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits workplace discrimination on any demographic attributes of an employee, racial discrimination frequently occurs even now in public sector organizations. For example, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2021) reported 22,064 complaints of race-based discrimination in FY 2020 and 30,938 complaints on average for the past decade (from FY 2010 to FY 2019). Recognizing the significant costs incurred from workplace discrimination, including decreased performance and increased turnover (Jones et al. 2016), many public administration scholars have attempted to investigate what individual or organizational factors are related to racial discrimination at public workplaces (Guul, Villadsen, and Wulff 2019).

As noted earlier, we are particularly interested in affective commitment and race-based discrimination at the collective level in public sector organizations because diversity is an organizational- or a unit-level attribute (Pitts and Wise 2010). According to organizational climate literature, employees are likely to form collective work attitudes because they work interdependently and share similar interpretations of the work environment (e.g., Conway and Briner 2012). This collective dynamic suggests that affective commitment climate can emerge in the organization through mutual interactions between employees. Similarly, aggregated formal race-based complaints represent a general measure of the degree of racially motivated employment discrimination in the organization. We therefore view racial diversity as having organizational-level relationships with collective affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination. In the following sections, we motivate these relationships with multiple theories.

Diversity, Commitment, and Discrimination

Workforce diversity can be conceptualized as “the degree to which a unit (e.g., a work group or organization) is heterogeneous with respect to demographic attributes” (Pelled, Eisenhardt, and Xin 1999, 1). Diversity is a compositional construct that exists at the collective level rather than the individual level because an individual within a unit is heterogeneous only in comparison with other individuals (Qin, Muenjohn, and Chhetri 2014). In line with this definition, scholars have proposed two types of diversity depending on the visibility of attributes: demographic diversity and task-related diversity (Horwitz and Horwitz 2007; Joshi, Liao, and Roh 2011). Demographic diversity refers to immediately observable categories, including gender, age, and race or ethnicity, whereas task-related diversity refers to unobservable categories that are germane to performing tasks, such as education, organizational tenure, and functional expertise (Horwitz and Horwitz 2007). Among the various types of demographic diversity, we are interested in racial diversity at the organizational level—the distribution of racial differences among the members of an organization—because of the increasing levels of racial diversity in public sector workforces over the past several decades (Choi 2010, 2011).

SCT largely supports the notion that demographic dissimilarities among organizational members may result in low levels of affective commitment climate (Tsui, Egan, and O’Reilly 1992). According to SCT, individuals have a strong desire to maintain high self-esteem by comparing themselves with others (Pitts and Towne 2015). In making these comparisons, individuals tend to use visible traits such as race as salient attributes to classify themselves and others into social categories (van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007). This classification process leads racially similar individuals to define themselves as members of an “in-group” but classify others who are racially dissimilar as “out-group” members (Joshi, Liao, and Jackson 2006). More importantly, employees show favoritism toward in-group members but hostility toward out-group members (Choi 2009; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). This distinction between in-group and out-group members engenders relational conflicts among employees that result in a lack of communication, reduced cooperation, and low levels of cohesiveness (Williams and O’Reilly 1998). Hence, these negative aspects of categorization processes undermine the development and sustainability of employees’ emotional attachment to the organization.

Research at the individual level provides an avenue for predicting collective-level relationships. For instance, Tsui, Egan, and O’Reilly (1992) have provided empirical evidence to support that a higher level of racial heterogeneity among employees was negatively related to the psychological commitment of the employees in the organization. Similarly, in a study of large British business schools, Kim et al. (2019) have reported that the race dissimilarity of students was negatively associated with emotional attachment to and behavioral involvement in the organization. These authors have suggested that motivated identity construction—SCT in particular—provides theoretical insights to explain how feelings of dissimilarity can lead to lower emotional and affective attachment to the larger collective. Based on these theoretical arguments and findings, we hypothesize that as racial diversity within an organization increases, employees are more likely to encounter relational conflict with those in different racial categories, which decreases affective commitment climate.

H1a: Racial diversity is negatively related to affective commitment climate.

In contrast to the negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment at the organizational level, we anticipate that racial diversity may be positively associated with race-based employment discrimination (see Supplementary Appendix 2). SCT provides theoretical insights to explain the positive relationship between racial diversity and employment discrimination (see Supplementary Appendix 3). For example, in-group favoritism and out-group hostility can fuel unlawful employment practices toward out-group members, including recruitment and promotion decisions, performance evaluations, job training, and career development (Shore and Goldberg 2005). Brewer (1991, 438) has noted that “ultimately, many forms of discrimination and bias may develop not because out-groups are hated, but because position emotions such as admiration, sympathy, and trust are reserved for the in-group and withheld from outgroups.” More importantly, in-group members may not explicitly perceive their in-group favoritism as discrimination if they see their behavior as legitimate and normative (Greenwald and Pettigrew 2014). Indeed, scholars have argued that group members expect other members who have similar characteristics to favor in-group members when allocating resources (Gaertner and Insko 2000) but show discriminatory behaviors toward out-group members by making fewer resource allocations (Locksley, Ortiz, and Hepburn 1980).

Notwithstanding this theoretical rationale, relatively few scholars have empirically studied how racial diversity relates to race-based employment discrimination (Avery, McKay, and Wilson 2008; Boehm et al. 2014). Avery, McKay, and Wilson (2008) have found that perceived racial discrimination was higher when greater racial dissimilarity existed between subordinates and supervisors at the individual level. Similarly, Boehm et al. (2014) have empirically proved that racial diversity is positively related to employees’ collective perception of the overall workplace discrimination in US military organizations. These studies have suggested that racial heterogeneity may prompt categorization processes and elicit race-based employment discrimination. Based on SCT, we expect the following:

H1b: Racial diversity is positively related to race-based employment discrimination.

Ethical Leadership, Commitment, and Discrimination

Leadership is a key factor to many public organizational outcomes (Van Wart 2013). If organizations seek to produce desired employee outcomes, some argue that the developmental process should start with leaders (Philipp and Lopez 2013). Our own research focus reflects growing scholarly interest in ethical leadership as a critical determinant of organizational outcomes in the field of public administration. For instance, scholars have proposed that leaders’ morality and ethics, as important characteristics of leadership effectiveness, shape work-related attitudes and behaviors (Hassan 2015; Hassan, Wright, and Yukl 2014).

According to the ethical leadership literature, the principal personal traits of ethical leaders are integrity (i.e., principled behavior), honesty (i.e., telling the truth), trust (i.e., can be trusted), respect (i.e., treatment of employees with respect and dignity), and the ability to listen (i.e., listening to employees’ concerns; Brown and Treviño 2006; Brown, Treviño, and Harrison 2005; Kalshoven, Den Hartog, and De Hoogh 2011). Although we capture these foundational traits through the measures used in this article, we recognize that more nuanced conceptualizations and measures of ethical leadership exist (see Supplementary Appendix 4).

Ethical leadership is conceptually similar to, but distinguishable from, other styles of leadership, including authentic, transactional, transformational, and servant leadership (Brown and Treviño 2006). First, ethical leadership overlaps with authentic leadership in that both leadership styles encourage followers to conduct ethical behaviors (Hoch et al. 2018). However, in contrast to the main focus of authentic leadership on self-awareness and self-concordance, ethical leadership primarily concerns compliance with normative standards or moral content (Lemoine, Hartnell, and Leroy 2019).

Second, ethical leadership shares some similarities with transactional leadership, given that both leadership styles use reinforcements to shape follower attitudes and behaviors. However, transactional leaders exercise rewards and punishments to encourage followers to improve their performance, whereas ethical leaders exercise the same to stimulate employees to act in an ethical manner (Toor and Ofori 2009).

Third, the idealized influence of transformational leadership can be associated with ethical leadership. In particular, transformational leaders serve as role models by behaving in ways that show followers high ethical values and responsibility (Bass 1985). Transformational leadership highlights ethics in a subsidiary manner in which ethics is one dimension of leadership (Kalshoven, Den Hartog, and De Hoogh 2011). In contrast, rather than focusing on being a role model, ethical leadership focuses on the demonstration of moral traits and ethically driven behavior to promote follower ethical behavior.

Finally, servant leadership—that aims to fulfill followers’ needs for well-being and personal development—shares some characteristics with ethical leadership, such as morality, integrity, and care for people (Greenleaf 1977). Whereas ethical leadership mainly focuses on directive and normative behaviors—that is, how things should be done according to ethical standards and rules—servant leadership has a stronger focus on the personal growth of followers and on why they want and can do things for themselves (van Dierendonck and Nuijten 2011). Thus, ethical leadership shares several commonalities with other leadership styles, but it also has lines of conceptual distinctions across the various styles (Avolio and Gardner 2005; Toor and Ofori 2009).

SET proposes that ethical leaders who treat their employees in a fair, respectful, and trustworthy manner strengthen the shared emotional attachment of employees to the organization by building a high-quality exchange relationship with them (Brown and Treviño 2006). For instance, Brown and Treviño (2006, 607) have noted that “the followers of ethical leaders are more likely to perceive themselves as being in social exchange relationships with their leaders because of the fair and caring treatment they receive and because of the trust they feel.” High-quality exchange relationships between ethical leaders and followers are characterized by the norm of reciprocity or by mutually reinforcing behaviors. For instance, extending SET, when an individual renders a favor to another, it often creates a sense of obligation to return that favor (Blau 1964). In other words, employees are likely to repay favorable treatment from their leaders in various forms of desired work outcomes and thus maintain high-quality exchange relationships (Mayer et al. 2009). The converse would also be true. When employees perceive their leaders to be dishonest, untruthful, and unfair, they develop low-quality exchange relationships with them, and disrespectful treatment leads to negative work-related outcomes.

Supporting this rationale, researchers have demonstrated that ethical leadership is a significant predictor of positive work attitudes—including employee job satisfaction (Moon and Jung 2018) and organizational commitment (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl 2014)—as well as work behaviors—including organizational citizenship (Resick et al. 2013) and innovative work behaviors (Yidong and Xinxin 2013). These studies indicate that when ethical leaders treat employees in a fair manner and listen to their concerns, employees are willing to reciprocate by demonstrating desired work attitudes and behaviors. We therefore hypothesize the following:

H2a: Ethical leadership is positively related to affective commitment climate.

SLT provides a theoretical basis for predicting that employees are likely to refrain from discriminatory behaviors against others by emulating the ethical behaviors of leaders (Brown and Treviño 2006; Philipp and Lopez 2013). Leaders convey particular messages or behavioral regulations to employees (Brown and Treviño 2006; Mayer et al. 2009). Through rewards and punishments, employees learn what kinds of behaviors are in line with accepted organizational norms or deviant from the interests of the organization (Mayer et al. 2012). Leaders serve as salient role models who inform employees about the benefits of appropriate behavior and costs of inappropriate behavior. Ethical leaders further encourage employees to engage in moral conduct and meet ethical expectations by displaying their attractive personal traits, such as integrity, honesty, and trustworthiness (Brown and Treviño 2006). Unethical modeling, on the contrary, induces employees to exhibit misconduct and counterproductive work behaviors, such as sabotage, discrimination, and lying to superiors (Brown, Treviño, and Harrison 2005; Mayer et al. 2012).

In support of this contention, some scholars have evidenced that managers can serve as ethical role models by encouraging employees to exhibit normative behaviors (Mayer et al. 2012) and to improve moral judgment (Steinbauer et al. 2014). We hypothesize that ethical leadership may reduce race-based employment discrimination in the workplace by shaping employees’ moral decision-making and action-taking through social learning processes.

H2b: Ethical leadership is negatively related to race-based employment discrimination.

The Moderating Effect of Ethical Leadership

Extending the reasoning that ethical leaders lead by example (Philipp and Lopez 2013), we expect ethical leadership to moderate the relationship between racial diversity and the affective commitment and discrimination, respectively. In this respect, Choi (2010, 609) has cogently noted that “managerial efforts may contribute to harmonizing differences of employees and reduce relational conflicts, alleviating the potential negative effects of demographic differences.” That is, although organizations have high levels of demographic diversity, the negative associations between diversity and work-related outcomes may be weakened depending on the effectiveness of ethical leadership in shaping social categorization processes.

Although both SET and SLT are intuitively and theoretically appealing to explain the relationships between racial diversity and the organizational outcomes, exactly how ethical leadership conditions such relationships is still unclear. One logical mechanism is to reduce the social categorization processes stemming from demographic diversity. ODT provides a useful framework for understanding the moderating role of ethical leadership; it focuses on the underlying process by which ethical leadership decreases categorical distinctions in organizations that are highly racially heterogeneous.

ODT posits that individuals try to enhance organizational identification by balancing two opposing needs: the needs for in-group belongingness and uniqueness from others (Brewer 1991). The need for belongingness motivates individuals to develop and maintain strong interpersonal relationships with other people, whereas the need for uniqueness motivates them to have a distinctive and differentiated self-concept (Shore et al. 2011). More concretely, as an individual’s sense of similarity to other organizational members increases, the need for belongingness is satisfied; because the need for belongingness is satisfied, the need for differentiation arises (Mor Barak 2016; Shore et al. 2011). In contrast, when an individual’s sense of dissimilarity to other organizational members increases, the need for uniqueness is satisfied, whereas the need for belongingness is triggered (Mor Barak 2016; Shore et al. 2011). Brewer (1991) has argued that an individual achieves an optimal level of organizational identification by simultaneously adjusting for deviations from the two countervailing needs for belongingness and uniqueness. That is, by satisfying the two opposing needs, employees feel a sense of inclusion wherein they perceive that the organization and leaders treat all employees as valued group members with unique characteristics regardless of demographic differences (Moon and Jung 2018). In this way, an organization can effectively manage demographic diversity through managerial efforts or practices that make employees feel included (Shore et al. 2011).

Extending ODT, ethical leadership may moderate the negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment climate by enhancing a sense of employee inclusion. Indeed, scholars have argued that perceived inclusion is a key building block to alleviate the relational conflict caused by social categorization (Mor Barak 2016; Shore et al. 2011). Given ethical leaders’ moral values and actions, ethical leaders allow employees to achieve an optimal satisfaction level of needs for both belongingness and uniqueness (Moon and Jung 2018). When their leaders treat them in a fair, respectful, and trustworthy manner regardless of their racial characteristics, employees feel that they are welcomed, valued organizational members (Shore et al. 2011). On the contrary, unfair and unfaithful treatments signal employees that their social group identity is not accepted and respected by the organization and its leaders, which impedes racially diverse employees from satisfying the need for belongingness.

Ethical leadership also allows employees to feel a high degree of uniqueness through the recognition of individual differences in decision-making processes and the formulation of relational transparency—that is, openness and dignity in interactions with employees (Boekhorst 2015). Hassan (2015) has offered evidence that ethical leadership is effective in engaging public employees in voice, suggesting that racially diverse employees under the supervision of ethical leaders may actively participate in decision-making processes including sharing divergent viewpoints and multiple opinions. When all employees have equal opportunities to express their suggestions and ideas, they perceive that leaders recognize their unique attributes as critical resources in organizational processes.

Extending our review of ODT, we hypothesize that ethical leaders can moderate the relationships between racial diversity and the two organizational outcomes (discrimination and affective commitment). In particular, ethical leaders who behave with integrity, honesty, and trustworthiness and who listen to employees’ suggestions help racially diverse employees to overcome social categorization processes by helping all employees to achieve the optimal level of organizational identification—the balance between the need for belongingness to an in-group and the need for uniqueness from others. All employees, regardless of race, feel more included in their organization when they experience ethical treatment from leaders. We reason that ethical leadership reduces in-group favoritism and out-group bias in racially heterogeneous organizations, thereby allowing employees to be emotionally attached to their organization and making them less inclined to engage in wrongdoings. We formalize these expectations as follows:

H3a: The negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment climate is moderated by ethical leadership such that it is weaker when ethical leadership is high compared to when it is low.

H3b: The positive relationship between racial diversity and race-based employment discrimination rates is moderated by ethical leadership such that it is weaker when ethical leadership is high compared to when it is low.

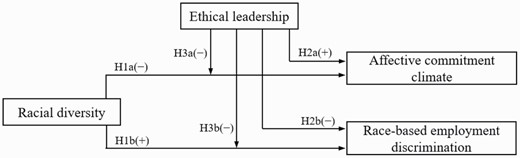

Figure 1 provides an overview of the hypothesized relationships in the conceptual model. To better understand the different facets of the general relationship between diversity, ethical leadership, and organizational outcomes, we “super-synthesize” multiple theories (John, 2012). H1a and H1b are based on SCT. H2a is based on SET and H2b on SLT. H3a and H2b are based on ODT. Synthesized, these theories articulate how ethical leaders influence the relationship between racial diversity and organizational outcomes by promoting social learning and employees’ needs for optimal distinctiveness.

Theorizing Ethical Leadership, Diversity, Commitment, and Discrimination.

Model Specification

Data

The units of analysis for this article are US federal subagencies. We integrated three different data sources: (1) Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS), (2) Enterprise Human Resources Integration Statistical Data Mart (EHRI-SDM), and (3) No FEAR Act Reports (NFRs) for the period 2010–15. We merged the data from FEVS, EHRI-SDM, and NFR using codes for the unique identification of subagencies (e.g., Veterans Health Administration [VATA] and Internal Revenue Service [TR93]). However, because all subagencies were not listed in each data source across time, our combined data set includes unbalanced panel data of 65 subagencies over the time period (see Supplementary Appendix 5).

FEVS

Using a stratified random sampling method, the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) annually administers FEVS to evaluate federal employees’ perceptions of human resource management practices and work-related attitudes. The number of respondents and response rates for the FEVS were, respectively, 263,475 and 52% (2010); 266,376 and 49.3% (2011); 687,687 and 46.1% (2012); 376,577 and 48.2% (2013); 392,752 and 46.8% (2014); and 421,748 and 49.7% (2015). All items drawn from the FEVS were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree or very dissatisfied) to 5 (strongly agree or very satisfied). However, conducting panel analysis at the individual level was impossible because the surveys are anonymous. Consequently, we averaged the individual responses to the organizational-level construct using the survey weights to conduct longitudinal analysis (see Supplementary Appendix 6).

EHRI-SDM

The second data source was EHRI-SDM, which is widely regarded as the most comprehensive data warehouse available on the size and scope of the federal workforce. It contains data about employment, accession, separation, employment trends, and diversity provided by approximately 120 federal subagencies, except some national security and intelligence agencies and the postal service.

NFR

The third data source was drawn from the NFRs published by each federal subagency. Since Congress enforced the “Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act of 2002” (known as the No FEAR Act), federal subagencies are required to post annual statistical data including filed complaints of employment discrimination on their public website. We extracted information about race-based discrimination from the reports for each fiscal year from 2010 to 2015.

Dependent Variables

Affective commitment and discrimination are often considered together in diversity research (Triana and Garcia 2009). Organizational-level or aggregated forms of these variables (e.g., affective commitment climate) are particularly useful for evaluating employees’ shared perceptions of their work environment (Kunze, Boehm, and Bruch 2011). Because affective commitment provides a window into workplace social exchange processes, together with observable discrimination claims measures, we argue that these dependent variables provide a reasonable way to assess how well racially diverse personnel are interacting in public agencies. We address each variable in turn.

Affective Commitment Climate

Affective commitment at the organizational level, or (aggregated) affective commitment climate (see Kunze, Boehm, and Bruch 2011), is a key dependent variable of interest because it provides a measure of social exchange climate. According to Allen and Meyer (1990, 2), affective commitment is defined as “affective or emotional attachment to the organization such that the strongly committed individual identifies with, is involved in, and enjoys membership in the organization.” Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) have further divided the concept of affective commitment into personal involvement, shared value, and identity relevance. Personal involvement indicates motivation for personal accomplishment, shared value represents the value congruence between an individual and the organization, and identity relevance refers to the desire for an individual identity by being associated with the organization as well as working within the organization (Moldogaziev and Silvia 2015).

The following three items were used to measure affective commitment: “My work gives me a feeling of personal accomplishment” (personal involvement), “I like the kind of work I do” (shared value), and “I recommend my organization as a good place to work” (identity relevance). Individual responses to the three items were averaged to represent affective commitment climate at the federal subagency level (see Supplementary Appendix 7). The Cronbach’s alphas for the scale ranged from 0.87 to 0.89 across years.

Race-Based Employment Discrimination (%)

Beyond attitudinal measures of collective attachment, we are interested in the observational measures of a subagency’s treatment of its employees. For these measures, we use the annual percentage of race-based employment discrimination. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2006), racial discrimination in the workplace refers to the unlawful treatment of an applicant or employee because of his or her race or personal features related to race, including hair texture, skin color, or facial characteristics. This discrimination also includes any aspect of unfair employment owing to an individual’s race, such as benefits, promotion, pay, and training. Reports from the No FEAR Act contain information about the number of racial discrimination complaints that subagencies received from their employees in the fiscal year. Many public administration scholars have used the ratio of employment discrimination complaints calculated from these reports as a proxy for the discriminatory experiences of employees in the workplace at the organizational level (Rubin and Kellough 2012). Using the reports of each subagency from 2010 to 2015, we measured race-based employment discrimination percentages by dividing the number of formal complaints filed about discrimination based on race by the total workforce size times one hundred.

Independent Variables

Racial Diversity

In this study, we defined demographic diversity as the degree of heterogeneity among employees with respect to their demographic attributes. We calculated racial diversity with Blau’s (1977) index of dissimilarity using the following formula: , where denotes the proportion of group members in the ith category. Drawing from EHRI-SDM’s categorization, we classified federal employees into five groups based on race: Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native Alaskan/American Indian, and White. The range of the index depended on the number of categories (i) ranging from 0 to (i − 1)/i. For example, when most federal employees in a subagency were different from each other in terms of race, the racial diversity index was close to 0.8.

Ethical Leadership

Brown, Treviño, and Harrison (2005) have enumerated the personal traits of ethical leaders to include integrity (i.e., principled behavior), honesty (i.e., telling the truth), trust (i.e., can be trusted), respect (i.e., treatment of employees with respect and dignity), and the ability to listen (i.e., listening to employees’ concerns).

Building on these components, we measured ethical leadership using the following four ordinal survey items: “My organization’s leaders maintain high standards of honesty and integrity” (integrity and honesty), “My supervisor/team leader treats me with respect” (respect), “I have trust and confidence in my supervisor” (trust) (see Supplementary Appendix 8), and “My supervisor/team leader listens to what I have to say” (ability to listen) (see Supplementary Appendix 9). The Cronbach’s alphas for the scale ranged from 0.78 to 0.79 across years. We averaged the ratings of the four items across respondents to create ethical leadership at the federal subagency level using the survey sampling weights.

Control Variables

We controlled for various organizational characteristics that may be related to affective commitment and race-based employment discrimination. First, we controlled for both diversity management and fairness of performance appraisal because employees are more likely to have a high level of emotional attachment to the organization and less likely to experience unlawful treatment in the organization if the organization implements the human resource practices that promote diversity and procedural justice (Shore et al. 2011). The following were the survey items for diversity management: “Policies and programs promote diversity in the workplace (for example, recruiting minorities and women, training in awareness of diversity issues, and mentoring),” “My supervisor/team leader is committed to a workforce representative of all segments of society,” and “Managers/supervisors/team leaders work well with employees of different backgrounds.” We measured the fairness of performance appraisal using a single item: “My performance appraisal is a fair reflection of my performance.”

Second, our model included whistle-blowing attitudes because employees are more likely to have high levels of loyalty to the organization and to file complaints of employment discrimination when they feel comfortable lending their voice and blowing the whistle (Caillier 2013; Lee and Whitford 2012). The item was as follows: “I can disclose a suspected violation of any law, rule, or regulation without fear of reprisal.”

Third, we controlled for the racial representation of management, which reflects the extent to which managers share the same racial characteristics with employees. According to the representative bureaucracy theory, employees are more likely to feel that they are valued and accepted group members in the organization when they are racially represented by their managers (Grissom and Keiser 2011; Oberfield 2016), a representation that may lead diverse employees to perceive that the organization treats them fairly. Racial representation of management was calculated by subtracting the percentage of minorities in the workforce from the percentage of minorities in managerial positions (GS 13 – GS 15); larger values are indicative of higher levels of representativeness (Oberfield 2016).

Fourth, lagged dependent variables were included to avoid potential omitted variable bias because they capture the observed and unobserved variables from the previous year (O’Toole and Meier 1999). Finally, we added both year and agency dummies into our models to account for time- and executive agency-specific effects. Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of the variables.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| . | . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affective commitment climate | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | Race-based employment discrimination | −0.24 | 1 | |||||||

| 3 | Racial diversity | −0.22 | 0.35 | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | Ethical leadership | 0.72 | −0.30 | −0.04ª | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Diversity management | 0.72 | −0.27 | −0.05ª | 0.85 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.68 | −0.26 | 0.00ª | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Fair evaluation for performance | 0.60 | −0.28 | 0.00ª | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1 | ||

| 8 | Racial representation of management | −0.08ª | −0.20 | −0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03ª | 1 | |

| 9 | Workforce size (1,000) | −0.08ª | −0.04ª | 0.18 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.12ª | −0.11ª | 1 |

| Mean | 3.92 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 3.84 | 3.70 | 3.58 | 3.73 | −3.85 | 16.76 | |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 6.66 | 39.95 | |

| Min | 3.22 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 3.40 | 3.17 | 2.84 | 3.25 | −33.97 | 0.16 | |

| Max | 4.31 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.19 | 4.20 | 30.87 | 327.93 |

| . | . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affective commitment climate | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | Race-based employment discrimination | −0.24 | 1 | |||||||

| 3 | Racial diversity | −0.22 | 0.35 | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | Ethical leadership | 0.72 | −0.30 | −0.04ª | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Diversity management | 0.72 | −0.27 | −0.05ª | 0.85 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.68 | −0.26 | 0.00ª | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Fair evaluation for performance | 0.60 | −0.28 | 0.00ª | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1 | ||

| 8 | Racial representation of management | −0.08ª | −0.20 | −0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03ª | 1 | |

| 9 | Workforce size (1,000) | −0.08ª | −0.04ª | 0.18 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.12ª | −0.11ª | 1 |

| Mean | 3.92 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 3.84 | 3.70 | 3.58 | 3.73 | −3.85 | 16.76 | |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 6.66 | 39.95 | |

| Min | 3.22 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 3.40 | 3.17 | 2.84 | 3.25 | −33.97 | 0.16 | |

| Max | 4.31 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.19 | 4.20 | 30.87 | 327.93 |

Note: aNot significant at 95% confidence interval.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| . | . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affective commitment climate | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | Race-based employment discrimination | −0.24 | 1 | |||||||

| 3 | Racial diversity | −0.22 | 0.35 | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | Ethical leadership | 0.72 | −0.30 | −0.04ª | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Diversity management | 0.72 | −0.27 | −0.05ª | 0.85 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.68 | −0.26 | 0.00ª | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Fair evaluation for performance | 0.60 | −0.28 | 0.00ª | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1 | ||

| 8 | Racial representation of management | −0.08ª | −0.20 | −0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03ª | 1 | |

| 9 | Workforce size (1,000) | −0.08ª | −0.04ª | 0.18 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.12ª | −0.11ª | 1 |

| Mean | 3.92 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 3.84 | 3.70 | 3.58 | 3.73 | −3.85 | 16.76 | |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 6.66 | 39.95 | |

| Min | 3.22 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 3.40 | 3.17 | 2.84 | 3.25 | −33.97 | 0.16 | |

| Max | 4.31 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.19 | 4.20 | 30.87 | 327.93 |

| . | . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affective commitment climate | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | Race-based employment discrimination | −0.24 | 1 | |||||||

| 3 | Racial diversity | −0.22 | 0.35 | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | Ethical leadership | 0.72 | −0.30 | −0.04ª | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Diversity management | 0.72 | −0.27 | −0.05ª | 0.85 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.68 | −0.26 | 0.00ª | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Fair evaluation for performance | 0.60 | −0.28 | 0.00ª | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1 | ||

| 8 | Racial representation of management | −0.08ª | −0.20 | −0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03ª | 1 | |

| 9 | Workforce size (1,000) | −0.08ª | −0.04ª | 0.18 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.12ª | −0.11ª | 1 |

| Mean | 3.92 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 3.84 | 3.70 | 3.58 | 3.73 | −3.85 | 16.76 | |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 6.66 | 39.95 | |

| Min | 3.22 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 3.40 | 3.17 | 2.84 | 3.25 | −33.97 | 0.16 | |

| Max | 4.31 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.19 | 4.20 | 30.87 | 327.93 |

Note: aNot significant at 95% confidence interval.

Methodology

To test our hypotheses, we used the feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) regression method because ordinary least squares analysis can generate biased and inefficient estimates when analyzing cross-sectional time series data. However, a concern when using panel data is the existence of year-to-year autocorrelation in and heteroskedasticity across panels. To investigate the presence of autocorrelation, we employed the Wooldridge test and found the F-statistics of 44.38 (p < .01) and 27.48 (p < .01) for the models, which indicated that the errors were serially correlated. In addition, the Breusch–Pagan test showed chi-squares of 34.85 (p < .01) and 455.42 (p < .01) for the models, providing evidence of heteroskedasticity. Therefore, we performed FGLS with a heteroskedastic error structure and AR(1) correction for autocorrelation in our analysis.

Findings

Independent Variables

Table 2 displays the results of the FGLS regression analyses of affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination. Our main independent variables largely exhibit significant, expected relationships. Model 2 confirms that racial diversity is significant and negative (β = −0.073; p < .05), supporting H1a that racial diversity is negatively related to affective commitment climate. In addition, H1b, regarding the positive relationship between racial diversity and race-based employment discrimination in federal agencies, is corroborated in model 5 (β = 0.274; p < .01). These findings suggest that an “us versus them” distinction in highly racially diversified organizations leads to intergroup bias, including in-group favoritism or prejudice. This bias thereby decreases the collective sense of emotional attachment to the organization and increases the occurrence of racial discrimination.

FGLS Regression Results

| . | Affective Commitment Climate . | . | . | . | . | . | Race-Based Employment Discrimination . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Model 1 . | . | Model 2 . | . | Model 3 . | . | Model 4 . | . | Model 5 . | . | Model 6 . | . |

| Racial diversity (RD) | −0.073 | [.044] | −1.803 | [.005] | 0.274 | [.000] | 3.122 | [.000] | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.644) | (0.058) | (0.818) | |||||||||

| Ethical leadership (EL) | 0.181 | [.006] | 0.032 | [.774] | −0.249 | [.014] | 0.042 | [.765] | ||||

| (0.065) | (0.110) | (0.101) | (0.139) | |||||||||

| RD × EL | 0.450 | [.007] | −0.739 | [.000] | ||||||||

| (0.168) | (0.211) | |||||||||||

| Dependent variable (lagged) | 0.917 | [.000] | 0.748 | [.000] | 0.683 | [.000] | 0.534 | [.000] | 0.469 | [.000] | 0.430 | [.000] |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | (0.035) | (0.028) | (0.033) | (0.035) | |||||||

| Diversity management | 0.117 | [.000] | 0.128 | [.017] | 0.149 | [.007] | 0.042 | [.477] | 0.085 | [.264] | 0.096 | [.218] |

| (0.029) | (0.054) | (0.056) | (0.060) | (0.076) | (0.078) | |||||||

| Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.026 | [.319] | −0.064 | [.136] | −0.037 | [.397] | −0.010 | [.854] | 0.109 | [.088] | 0.094 | [.159] |

| (0.026) | (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.054) | (0.064) | (0.067) | |||||||

| Fair evaluation for performance | −0.022 | [.193] | 0.005 | [.822] | 0.017 | [.508] | −0.154 | [.000] | −0.158 | [.000] | −0.144 | [.001] |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.044) | |||||||

| Racial representation of management | −0.001 | [.000] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.002] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.004] |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Workforce size (log) | −0.005 | [.012] | −0.002 | [.430] | −0.002 | [.627] | −0.016 | [.002] | −0.023 | [.000] | −0.025 | [.000] |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Constant | −0.051 | [.505] | 0.089 | [.434] | 0.936 | [.004] | 0.692 | [.000] | 1.056 | [.000] | −0.075 | [.843] |

| (0.076) | (0.114) | (0.328) | (0.153) | (0.171) | (0.377) | |||||||

| Year-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Agency-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Wald χ 2 | 10,304.56 | [.000] | 3,894.75 | [.000] | 3,775.54 | [.000] | 3,748.65 | [.000] | 1,773.63 | [.000] | 1,436.88 | [.000] |

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 |

| . | Affective Commitment Climate . | . | . | . | . | . | Race-Based Employment Discrimination . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Model 1 . | . | Model 2 . | . | Model 3 . | . | Model 4 . | . | Model 5 . | . | Model 6 . | . |

| Racial diversity (RD) | −0.073 | [.044] | −1.803 | [.005] | 0.274 | [.000] | 3.122 | [.000] | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.644) | (0.058) | (0.818) | |||||||||

| Ethical leadership (EL) | 0.181 | [.006] | 0.032 | [.774] | −0.249 | [.014] | 0.042 | [.765] | ||||

| (0.065) | (0.110) | (0.101) | (0.139) | |||||||||

| RD × EL | 0.450 | [.007] | −0.739 | [.000] | ||||||||

| (0.168) | (0.211) | |||||||||||

| Dependent variable (lagged) | 0.917 | [.000] | 0.748 | [.000] | 0.683 | [.000] | 0.534 | [.000] | 0.469 | [.000] | 0.430 | [.000] |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | (0.035) | (0.028) | (0.033) | (0.035) | |||||||

| Diversity management | 0.117 | [.000] | 0.128 | [.017] | 0.149 | [.007] | 0.042 | [.477] | 0.085 | [.264] | 0.096 | [.218] |

| (0.029) | (0.054) | (0.056) | (0.060) | (0.076) | (0.078) | |||||||

| Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.026 | [.319] | −0.064 | [.136] | −0.037 | [.397] | −0.010 | [.854] | 0.109 | [.088] | 0.094 | [.159] |

| (0.026) | (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.054) | (0.064) | (0.067) | |||||||

| Fair evaluation for performance | −0.022 | [.193] | 0.005 | [.822] | 0.017 | [.508] | −0.154 | [.000] | −0.158 | [.000] | −0.144 | [.001] |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.044) | |||||||

| Racial representation of management | −0.001 | [.000] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.002] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.004] |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Workforce size (log) | −0.005 | [.012] | −0.002 | [.430] | −0.002 | [.627] | −0.016 | [.002] | −0.023 | [.000] | −0.025 | [.000] |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Constant | −0.051 | [.505] | 0.089 | [.434] | 0.936 | [.004] | 0.692 | [.000] | 1.056 | [.000] | −0.075 | [.843] |

| (0.076) | (0.114) | (0.328) | (0.153) | (0.171) | (0.377) | |||||||

| Year-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Agency-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Wald χ 2 | 10,304.56 | [.000] | 3,894.75 | [.000] | 3,775.54 | [.000] | 3,748.65 | [.000] | 1,773.63 | [.000] | 1,436.88 | [.000] |

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses and p-values in brackets.

FGLS Regression Results

| . | Affective Commitment Climate . | . | . | . | . | . | Race-Based Employment Discrimination . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Model 1 . | . | Model 2 . | . | Model 3 . | . | Model 4 . | . | Model 5 . | . | Model 6 . | . |

| Racial diversity (RD) | −0.073 | [.044] | −1.803 | [.005] | 0.274 | [.000] | 3.122 | [.000] | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.644) | (0.058) | (0.818) | |||||||||

| Ethical leadership (EL) | 0.181 | [.006] | 0.032 | [.774] | −0.249 | [.014] | 0.042 | [.765] | ||||

| (0.065) | (0.110) | (0.101) | (0.139) | |||||||||

| RD × EL | 0.450 | [.007] | −0.739 | [.000] | ||||||||

| (0.168) | (0.211) | |||||||||||

| Dependent variable (lagged) | 0.917 | [.000] | 0.748 | [.000] | 0.683 | [.000] | 0.534 | [.000] | 0.469 | [.000] | 0.430 | [.000] |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | (0.035) | (0.028) | (0.033) | (0.035) | |||||||

| Diversity management | 0.117 | [.000] | 0.128 | [.017] | 0.149 | [.007] | 0.042 | [.477] | 0.085 | [.264] | 0.096 | [.218] |

| (0.029) | (0.054) | (0.056) | (0.060) | (0.076) | (0.078) | |||||||

| Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.026 | [.319] | −0.064 | [.136] | −0.037 | [.397] | −0.010 | [.854] | 0.109 | [.088] | 0.094 | [.159] |

| (0.026) | (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.054) | (0.064) | (0.067) | |||||||

| Fair evaluation for performance | −0.022 | [.193] | 0.005 | [.822] | 0.017 | [.508] | −0.154 | [.000] | −0.158 | [.000] | −0.144 | [.001] |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.044) | |||||||

| Racial representation of management | −0.001 | [.000] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.002] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.004] |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Workforce size (log) | −0.005 | [.012] | −0.002 | [.430] | −0.002 | [.627] | −0.016 | [.002] | −0.023 | [.000] | −0.025 | [.000] |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Constant | −0.051 | [.505] | 0.089 | [.434] | 0.936 | [.004] | 0.692 | [.000] | 1.056 | [.000] | −0.075 | [.843] |

| (0.076) | (0.114) | (0.328) | (0.153) | (0.171) | (0.377) | |||||||

| Year-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Agency-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Wald χ 2 | 10,304.56 | [.000] | 3,894.75 | [.000] | 3,775.54 | [.000] | 3,748.65 | [.000] | 1,773.63 | [.000] | 1,436.88 | [.000] |

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 |

| . | Affective Commitment Climate . | . | . | . | . | . | Race-Based Employment Discrimination . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Model 1 . | . | Model 2 . | . | Model 3 . | . | Model 4 . | . | Model 5 . | . | Model 6 . | . |

| Racial diversity (RD) | −0.073 | [.044] | −1.803 | [.005] | 0.274 | [.000] | 3.122 | [.000] | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.644) | (0.058) | (0.818) | |||||||||

| Ethical leadership (EL) | 0.181 | [.006] | 0.032 | [.774] | −0.249 | [.014] | 0.042 | [.765] | ||||

| (0.065) | (0.110) | (0.101) | (0.139) | |||||||||

| RD × EL | 0.450 | [.007] | −0.739 | [.000] | ||||||||

| (0.168) | (0.211) | |||||||||||

| Dependent variable (lagged) | 0.917 | [.000] | 0.748 | [.000] | 0.683 | [.000] | 0.534 | [.000] | 0.469 | [.000] | 0.430 | [.000] |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | (0.035) | (0.028) | (0.033) | (0.035) | |||||||

| Diversity management | 0.117 | [.000] | 0.128 | [.017] | 0.149 | [.007] | 0.042 | [.477] | 0.085 | [.264] | 0.096 | [.218] |

| (0.029) | (0.054) | (0.056) | (0.060) | (0.076) | (0.078) | |||||||

| Whistle-blowing attitudes | 0.026 | [.319] | −0.064 | [.136] | −0.037 | [.397] | −0.010 | [.854] | 0.109 | [.088] | 0.094 | [.159] |

| (0.026) | (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.054) | (0.064) | (0.067) | |||||||

| Fair evaluation for performance | −0.022 | [.193] | 0.005 | [.822] | 0.017 | [.508] | −0.154 | [.000] | −0.158 | [.000] | −0.144 | [.001] |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.044) | |||||||

| Racial representation of management | −0.001 | [.000] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.002] | −0.002 | [.001] | −0.002 | [.004] |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Workforce size (log) | −0.005 | [.012] | −0.002 | [.430] | −0.002 | [.627] | −0.016 | [.002] | −0.023 | [.000] | −0.025 | [.000] |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Constant | −0.051 | [.505] | 0.089 | [.434] | 0.936 | [.004] | 0.692 | [.000] | 1.056 | [.000] | −0.075 | [.843] |

| (0.076) | (0.114) | (0.328) | (0.153) | (0.171) | (0.377) | |||||||

| Year-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Agency-specific effect | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Wald χ 2 | 10,304.56 | [.000] | 3,894.75 | [.000] | 3,775.54 | [.000] | 3,748.65 | [.000] | 1,773.63 | [.000] | 1,436.88 | [.000] |

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses and p-values in brackets.

H2a proposed that ethical leadership is positively related to affective commitment climate. The hypothesis is confirmed (β = 0.181; p < .01) in model 2. The results of model 5 show that ethical leadership is negatively associated with race-based employment discrimination (β = −0.249; p < .05), also supporting H2b. In return for ethical and fair treatment from their leaders, employees under ethical leadership are more likely to have a favorable orientation and attachment to their organization and to internalize a moral perspective.

Moderating Variables

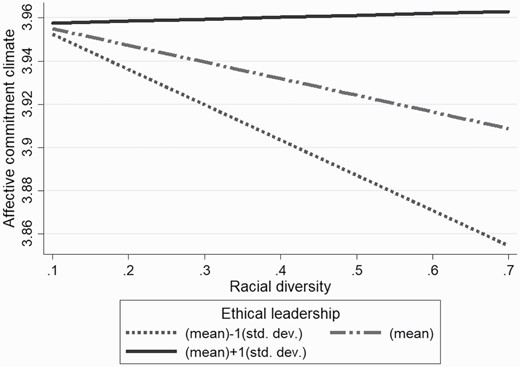

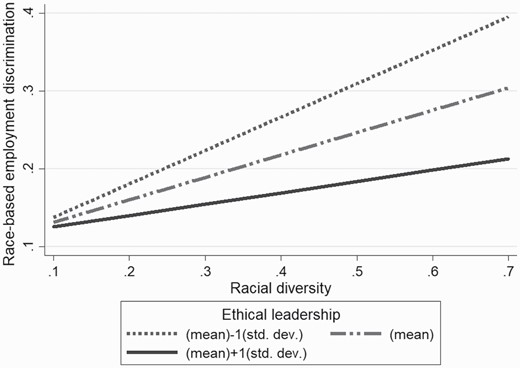

The prior models serve as important reference points for our primary models of interest. We added interactions between racial diversity and ethical leadership in models 3 and 6 to better explore ODT. The results indicate that ethical leadership significantly moderates the negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment (β = 0.450; p < .01), which is consistent with H3a. Moreover, ethical leadership significantly moderates the positive relationship between racial diversity and race-based employment discrimination (β = −0.739; p < .01), thus supporting H3b.

The patterns of the interaction between racial diversity and ethical leadership on affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination are visualized in figures 2 and 3, respectively. Consistent with our expectation, figure 2 shows that when ethical leadership is high—that is, 1 standard deviation (SD) above the mean (indicated by the solid line)—the negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment climate is significantly weaker than that when ethical leadership is low—that is, 1 SD below the mean (indicated by the dotted line). Similarly, figure 3 confirms that racial diversity has a positive association with race-based employment discrimination but that the slope of its negative association is attenuated when ethical leadership is high. In sum, the results of our moderated models suggest that ethical leadership allows employees to experience feelings of inclusion by reducing intergroup bias and conflict flowing from social categorization processes. These feelings of inclusion, in turn, increase affective commitment climate and decrease race-based employment discrimination.

Interactions Between Racial Diversity and Ethical Leadership for Affective Commitment Climate.

Interactions Between Racial Diversity and Ethical Leadership for Race-Based Employment Discrimination.

Control Variables

Most of the control variables exhibit the expected signs and some are statistically significant. First, models 1 and 4 show strong associations between the lagged dependent variables and present dependent variables. This association indicates an organizational inertia in which current affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination are predicted by previous ones (O’Toole and Meier 1999).

Second, the results of model 1 show that diversity management is a significant predictor of affective commitment climate; organizational policies promoting diversity shape employees’ shared emotional attachment to their organization. Racial representation of management is another significant predictor of affective commitment climate, which is inconsistent with our expectation on its positive relationship with affective commitment climate. One possible explanation is that employees could collectively form in-group/out-group distinctions that lead to dysfunctional conflict and reduced affective commitment across work groups in the organization where the racial composition of the managerial workforce is highly representative of group members. For instance, management, a traditionally majority occupation, may generate in-group favoritism and out-group bias for the minority in management positions (Schwab et al. 2016). This means that minority managers in the organization with high levels of racial representation of management are likely to engage in unfavorable treatment toward out-group employees who have different racial backgrounds. Moreover, the results present that workforce size is negatively associated with affective commitment climate. Employees in larger organizations have fewer meaningful interactions with others—that may result in weaker interpersonal connections and lower levels emotional attachment to the organizations—than those in smaller organizations (Andrews 2017).

Finally, model 4 confirms that fair evaluation for performance is negatively related to race-based employment discrimination; a fair performance appraisal system regardless of racial identities prevents employment discrimination claims by employees (Goldman 2001). The results also show that the racial representation of management is negatively associated with race-based employment discrimination. It is plausible that employees collectively exhibit nondiscriminatory behaviors when leaders proportionally represent them in terms of race. In addition, the results show that there is a negative relationship between workforce size and race-based employment discrimination. Our interpretation is that the larger the size of an organization, the more resources available to create equal and nondiscriminatory organizational practices; thus, employees can be treated in a fair manner regardless of their racial backgrounds (Banerjee, Reitz, and Oreopoulos 2018).

Discussion

Our findings, which come from a panel of US federal agencies, suggest that ethical leadership significantly attenuates the negative relationship of racial diversity with affective commitment climate and the positive relationship of racial diversity with race-based employment discrimination. We discuss several important implications of these results for research and practice.

Theoretical Implications

Despite the steep rise of scholarly interest in the work-related outcomes of demographic diversity (Pitts and Wise 2010; Sabharwal, Levine, and D’Agostino 2018), very few empirical studies have been conducted on how racial diversity is associated with a collective norm of commitment to the organization and with unequal treatment based on race in the public sector. More importantly, public administration scholars have less insight on the role of ethical leadership as a contextual moderator in managing these key relationships. In this article, we address these research gaps by extending an integrative theoretical framework (figure 1) that serves as a guide to help future research better understand the meaning and significance of racial diversity and ethical leadership in the public workforce. Consistent with John’s (2012) and Cairney’s (2013) general arguments, whereas a single theory can be incomplete, theoretical combinations can pave the way for exploring the effective management of racially diverse employees in the US federal government (Roberson, Ryan, and Ragins 2017).

First, our findings suggest that employees in organizations with higher levels of racial diversity may experience more relational conflicts and intergroup prejudice stemming from social categorization processes. These can ultimately lead to low levels of affective commitment climate and high levels of race-based employment discrimination. Along these lines, our results are consistent with the logic of SCT. Although mixed empirical findings concerning the relationships between racial diversity and various organizational outcomes pervade the literature (Joshi, Liao, and Roh 2011), thus raising doubts about the assumptions of SCT, our evidence indicates that SCT is still a powerful theoretical rationale to predict the organizational outcomes of racial diversity.

Second, our evidence confirms that SET and SLT provide the core theoretical foundations to anticipate the organizational outcomes of ethical leadership at the collective level. Following Hassan, Wright, and Yukl’s (2014) call for future research on ethical leadership in public sector organizations, we have identified how ethical leadership relates to affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination in US federal agencies. In keeping with SET, our findings indicate that federal employees are more likely to perceive themselves as being in a social exchange relationship with their leaders when they are treated with respect and integrity by their leaders. That is, employees experiencing high levels of ethical leadership are willing to reciprocate by being highly committed to the organization. Moreover, our results confirm the premise of SLT: employees are likely to emulate the personal traits and behaviors of ethical leaders, extending fair and honest treatment to others in the same manner in which they receive it from ethical leaders. In other words, employees try to model ethical leaders by not engaging in employment discrimination in the workplace. Our multi-theory synthesis is likely to be more fruitful than a single theory in predicting the complex work-related outcomes influenced by ethical leadership.

With respect to the findings on the outcomes of ethical leadership, this article also contributes to the field of public administration by describing the important role of ethical leaders in promoting ethics as a core principle of civil service (Downe, Cowell, and Morgan 2016). Considering scholars’ considerable and recent attention to market-based governance and economic efficiency, which may undermine ethical public organizations (e.g., Roberson, Ryan, and Ragins 2017), ethical leadership may shape core public service values—including fairness, respect, and morality—especially in a racially diverse workforce. Moreover, the relationship between ethical leadership and public service motivation may have unique applications and consequences in the public sector (Potipiroon and Ford 2017), where ethical leaders may, for example, increase employee public service motivation through behavioral role modeling (Wright, Hassan, and Park 2016). Therefore, it would be worthwhile for public administration scholars to explore the outcomes of ethical leadership as well as its determinants in the work context of public sector organizations (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl 2014). That said, we do not eschew the possibility that these findings (e.g., ethical leadership mitigating the association of diversity to discrimination claims) may also be useful in better understanding private sector organizations.

Finally, we advance the diversity and leadership literature by integrating SCT and ODT in our theoretical model. Indeed, this article is among the first to examine the moderating role of ethical leadership in the relationships between racial diversity and organizational outcomes. As leadership styles are often shown to shape work-related outcomes when interacting in organizational contexts (Den Hartog, De Hoogh, and Keegan 2007), disentangling how ethical leadership conditions the relationships of racial diversity with affective commitment climate and race-based employment discrimination is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of ethical leadership. For instance, considering that the negative organizational outcomes of racial diversity are attributable to social categorization biases, we relied on ODT as a theoretical lens to explain ethical leadership as a key moderator that helps employees to achieve an optimal level of needs for both belongingness and uniqueness.

This article shows that ethical leadership reduces the negative relationship between racial diversity and affective commitment climate as well as the positive relationship between racial diversity and race-based employment discrimination. Our findings suggest that even if employees in highly racially diverse agencies engage in social categorization processes, they feel included and perceive that they are all crucial members of the same group under high levels of ethical leadership. The moral characteristics and ethical behaviors of leaders appear to encourage employees to avoid social categorization processes and experience inclusion regardless of their in-group or out-group status. This article ultimately recommends ODT, SLT, and SET as promising theoretical tools to study how leaders might navigate the competing, often negative, tensions introduced by SCT.

Practical Implications

Our article demonstrates the possibility of a practical path to navigate the fact that racial diversity can be a “double-edge sword” with both negative (Choi 2009) and positive (Moon 2018) organizational effects. Studies have shown that this path is, among other things, contingent on the different levels of diversity within the organization (curvilinear relationship) and the types of organizational outcomes (Horwitz and Horwitz 2007). Our article confirms that more racially heterogeneous agencies show lower levels of a collective sense of emotional attachment to the subagency. These agencies also show more race-related discrimination incidents than the subagencies with a workforce that is less racially heterogeneous.

However, we affirm that racial diversity, particularly under the right leadership, can lead to benefits for organizations. More importantly, this article advocates ethical leadership as a critical tool for effective diversity management and that ethical leadership matters more in agencies that are highly racially diversified. Ethical managers can enhance employees’ loyalty and emotional attachment to the organization and deter race-based employment discriminatory actions in the workplace.

In light of these findings, federal agencies will benefit from managerial efforts aimed at hiring and developing ethical leaders. Pursuant to the Evidence Act, federal agency learning agendas (see Young 2013) could focus on leadership training that recognizes the reality of social categorization (SCT), including implicit bias while facilitating conversations around social learning (SLT), social exchange (SET), and employee psychological needs such as optimal distinctiveness (ODT). These can include peer- and case-based discussions. Such programs are useful to challenge managers’ perceptions about ethical dilemmas and highlight critical ethical considerations (Neves and Story 2015; Walumbwa et al. 2011). Furthermore, during the hiring process, agencies may want to signal to job candidates that moral traits and ethical behaviors, such as fairness, integrity, honesty, trustworthiness, and the ability to listen to employees’ concerns, are key factors of qualified managers (Mayer et al. 2012). Integrity assessment tests (see Fine 2013) or discussing moral issues in job interviews can be effective in selecting more ethical leaders who have strong moral awareness and respect for employees in management.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of this article should be addressed for future research. First, because our study relied on data from the US federal government for a certain period (2010–15), it is plausible that empirical studies in different countries and concerning longer or different periods of time may produce different evidence.

Second, we recognize that ethical leadership and affective commitment are not measured using the same items employed in prior research. Although the measures reflect multiple traits of ethical leaders and affective commitment, one may criticize the construct validity. Although not unique to our field, this challenge is often faced in the field of public administration when relying on existing secondary data, such as FEVS, which aims to capture the perceptions of federal employees on workplace conditions. For example, although ethical leadership is commonly characterized by the aspects of both moral person and moral manager (Brown and Treviño 2006; Brown, Treviño, and Harrison 2005), our measure of ethical leadership is arguably more conceptually proximate to the moral person traits representing integrity, trustworthiness, honesty, and concern for others. FEVS does not include items that would allow us to effectively assess the attributes of moral manager that emphasize leaders’ transactional efforts to shape the ethical behavior of followers. Similarly, the shortened scale of affective commitment used in this article does not accurately capture commitment as conceptualized by Meyer and Allen (1997) because of data limitations. Hence, we acknowledge that future research could improve the measure of ethical leadership and affective commitment using, for example, the 10-item ethical leadership scale created by Brown, Treviño, and Harrison (2005) and the six-item scale of affective commitment to an organization developed by Meyer and Allen (1997).

Third, we note the methodological problems associated with the aggregation of the lower-level (individual) data into the higher level (organizational) of analysis when computing the average value of individual responses within an organization and performing the analysis at the higher level. Therefore, individual-level predictors to the organizational level may provide misleading findings because the aggregation of individual data fails to model sampling error and thus generates bias parameter estimates (Croon and van Veldhoven 2007). Previous studies have recommended using multilevel techniques to overcome the methodological problems of data aggregation (Bennink, Croon, and Vermunt 2013). In addition, with respect to the aggregation approach, our findings conceivably exhibit some environmental bias caused by the organizational context that induces survey respondents within the same organization to exhibit similar perceptual biases (Favero and Bullock 2015). For example, some organizational factors—including organizational culture, hiring and socialization processes, and organizational values—artificially shape similar perceptions across employees about various dimensions of their workplace (Favero and Bullock 2015). We look forward to exploring the sensitivity of our findings to such limitations, should data collection efforts in the future remedy these weaknesses. Another limitation related to the level of aggregation is our inability to actually measure leader-groups, perceived in-groups, and perceived out-groups. It is entirely possible, for example, that regardless of whether one is a member of the in- or out-group, commitment to the organization (subagency) will be similar. Whereas some research raises the possibility that certain employees may “consider the organization as an in-group” (Francesco and Chen 2004, 428), we hope future work on this question will better isolate the role of groupings or levels nested within broad units of analysis (e.g., subagencies).

Finally, our unit of analysis was the organization. One should take into account the potential problems of ecological fallacy because the findings derived from organizational-level data may not be applicable to the individual level. In addition, OPM does not provide clear information in the items of FEVS about which organizational levels (e.g., work group, subagency, and agency) the term “organization” exactly refers to. This limitation may lead to unclear units of analysis and become particularly problematic because the operational definitions of our measures using FEVS could possibly capture a different unit than the theoretical concepts.

Conclusion