-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Katlyn Garr, Cathleen Odar Stough, Julianne Origlio, Family Functioning in Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Systematic Review, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 46, Issue 5, June 2021, Pages 485–500, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab007

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Children with some chronic health conditions experience family functioning difficulties. However, research examining family functioning in youth with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) has produced mixed results. Therefore, the current review critically synthesized the literature on family functioning among youth with FGIDs.

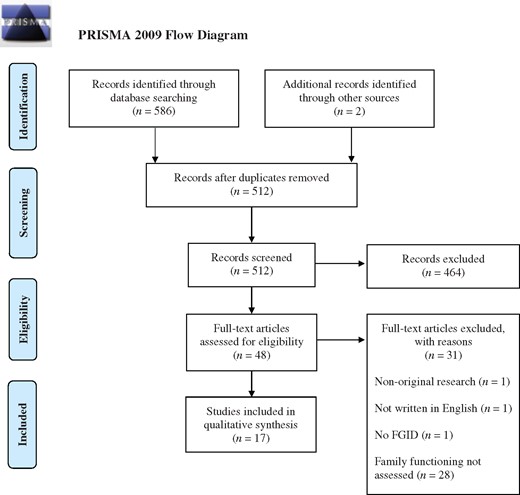

A systematic search using pediatric, family functioning, and FGID search terms was conducted in PubMed, PsycInfo, and ProQuest. Out of the 586 articles initially identified, 17 studies met inclusion criteria. Studies were included if they presented original research in English, assessed family functioning, and the study sample consisted of children (0–18 years) diagnosed with a FGID. Quality assessment ratings were conducted for each included study based on a previously developed scientific merit 3-point rating system.

The majority of studies (n = 13) examined family functioning between youth with FGIDs and comparison groups. The remaining studies explored associations between family functioning and study variables (e.g., child psychosocial functioning and sociodemographic factors) and examined family functioning clusters among children with FGIDs. In general, children with FGIDs demonstrated poorer family functioning compared to healthy counterparts. Findings also suggested that child psychosocial functioning, disease characteristics, and sociodemographic factors were related to family functioning among youth with FGIDs. The average quality of studies was moderate (M = 2.3).

Maintaining healthy family functioning appears to be challenging for some families of children with FGIDs. Future research should explore the directionality of the relationship between family functioning and child physical and psychosocial outcomes to advance the understanding and treatment of pediatric FGIDs.

Introduction

Pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are a complex set of gut-brain interaction disorders characterized by chronic and painful gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation) influenced by physical and psychological factors (Drossman, 2016; Rome Foundation, 2020). FGIDs affect approximately 30% of children worldwide (Boronat et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2016; Robin et al., 2018), with some of the most common disorders being functional abdominal pain (FAP), functional constipation (FC), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS; Lewis et al., 2016). Children with FGIDs often experience significantly impaired physical functioning (e.g., frequent medical appointments, unexpected procedures/surgeries, hospitalizations; Robin et al., 2018) and psychosocial functioning (e.g., poor quality of life, mental health problems, decreased school functioning; Hommel et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2016; Varni et al., 2015; Waters et al., 2013). Furthermore, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that pediatric FGIDs often continue into adulthood (Chiou & Nurko, 2011).

Due to the complexities of FGIDs, the Rome Foundation, a team of gastroenterology experts, created evidence-based FGID diagnostic criteria (i.e., Rome criteria) that undergoes regular revisions to include newfound FGID knowledge (Rome Foundation, 2020). The Rome Foundation applies a biopsychosocial model to understand and treat FGIDs, where a bidirectional interaction of biological (e.g., genetics, inflammation) and psychosocial (e.g., stress, social support) factors produce gut-brain dysfunction (Drossman, 2016). For example, individuals with FGIDs may experience visceral hypersensitivity (e.g., rumbling in stomach), which signals a potential threat to homeostasis (e.g., “something must be wrong”) and results in a behavioral response (e.g., staying home from school), which then reinforces the cycle (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016). FGID treatments target a range of biopsychosocial factors depending on symptom severity. For example, treatment for mild symptomatology may consist of psychoeducation and diet modification, whereas treatment for moderate-to-severe symptomatology may consist of medication and psychological treatments (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, family-based interventions; Drossman, 2016). Addressing modifiable factors (e.g., diet, mental health) to improve quality of life and reduce functional impairment are the primary goals of FGID treatment (Drossman, 2016). One understudied modifiable factor that may have important treatment implications for FGIDs is family functioning.

Family systems theories are founded on the idea that families are integrated, complex units and individual functioning cannot be understood without examining family functioning (Cox & Paley, 1997; Miller et al., 2000). Family functioning refers to the “structural and social properties of the global family environment,” with key properties including family communication, organization, roles, cohesion, conflict, emotional and behavioral responsiveness, and problem-solving (Alderfer et al., 2008; Lewandowski et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2000). Characteristics of healthy family functioning may consist of open and direct communication, clear role expectations, and well-regulated emotions and behaviors, while unhealthy family functioning characteristics may involve disorganization, poor communication, and high levels of conflict (Alderfer et al., 2008; Lewandowski et al., 2010).

Family functioning is often examined in pediatric populations since families of children with chronic health conditions sometimes experience family functioning difficulties (e.g., Lewandowski et al., 2010; Van Schoors et al., 2017). Parents of children with chronic health conditions are disproportionately affected by challenges such as financial stress (e.g., medical bills), daily life disruptions (e.g., staying home from work when the child is sick), and disease uncertainty (Palermo & Eccleston, 2009). However, the findings regarding family functioning in pediatric FGIDs are mixed. For example, one study found that families of children with FGIDs display more dysfunction in communication, roles, and problem-solving than families of healthy children (Liakopoulou-Kairis et al., 2002). Wang et al. (2013) also identified that families of children with FGIDs reported worse family relationships and overall family functioning when compared to families of healthy children. However, other literature suggests that families of children with FGIDs do not experience family functioning difficulties (Sanders et al., 1990; Wasserman et al., 1988). Another study found that families of children with FGIDs had better family relationships when compared to families of children with psychiatric disorders (Walker et al., 1993). These mixed results may be due to the many challenges that accompany examining family functioning among children with FGIDs, including the broad definitions and classifications of family functioning and difficulties differentiating between FGID symptomatology and diagnosis.

Adopting a family systems framework to pediatric FGIDs may help to understand how family characteristics influence the child’s physical and psychosocial functioning (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016). Specific family functioning domains that may uniquely relate to FGIDs are roles, affective responsiveness and involvement, and behavior control (e.g., Cengel-Kultur et al., 2014; Liakopoulou-Kairis et al., 2002). For example, a family that has well-defined roles and a plan for when the child experiences a GI episode may provide comfort and security for the child, mitigating the episode. In contrast, a family that displays low affective responsiveness and dismisses the child’s GI symptoms could lead the child to feel unsupported and anxious, exacerbating the GI episode. The relationship between family functioning, child GI symptoms, and child psychosocial functioning is consistent with a biopsychosocial framework and is plausible due to the interference of stress and emotional arousal on healthy GI functioning (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016).

The inconsistent findings in the family functioning and pediatric FGID literature creates a significant gap in knowledge as to whether children with FGIDs and their families experience family functioning challenges, hindering the conclusions that can be drawn to inform FGID research and treatment efforts. Therefore, the current project systematically reviewed studies examining family functioning among children and adolescents with FGIDs. Synthesizing such findings will inform us if family functioning differs among children with FGIDs and healthy children and if family functioning influences child physical (e.g., GI symptoms, pain) and psychosocial (e.g., quality of life, depression) functioning. If so, family functioning may be an important factor to target in pediatric FGID treatment.

Method

Search Strategy

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global in January 2020. Theses and dissertations were included in the current review to reduce the risk of bias and provide the most updated and relevant research available (Higgins & Green, 2008; Paez, 2017). Previously established and validated pediatric search terms for systematic searches were used as a guide for the current search (Leclercq et al., 2013); these terms were: “infant OR baby OR child OR children OR adolescent OR adolescence OR youth OR teen OR teenager OR young adult OR emerging adult OR pediatric OR paediatric.” The Rome Foundation’s guidelines were used to determine pediatric FGID search terms (Drossman, 2016; Rasquin et al., 2006), which were: “Functional gastrointestinal disorder OR functional rumination OR rumination syndrome OR cyclic vomiting syndrome OR aerophagia OR abdominal migraine OR recurrent abdominal pain OR functional abdominal pain OR functional dyspepsia OR irritable bowel syndrome OR nonretentive fecal incontinence OR functional constipation.” For family functioning search terms, a preliminary search was conducted to identify common keywords and terms in the family functioning literature (Alderfer et al., 2008; Lewandowski et al., 2010); the following terms were used: “family functioning OR family environment OR family relations OR family system OR family health OR family cohesion OR family communication OR family conflict OR family organization OR family OR parenting style OR parenting practices OR parent-child OR parent OR parenting OR parental.” Articles had to have a search term from all three categories (i.e., pediatric, FGID, and family functioning) to be reviewed for study inclusion. The “abstract” filter (i.e., the search term had to be present in the title or abstract) was applied when searching for articles in all search engines.

Study Selection

A total of 586 articles were identified through searches. Seventy-six duplicates were identified and removed, leaving a total of 510 unique articles. Two articles were identified through searching reference lists of included articles and forward reference searching (i.e., identifying articles that cite the included articles) via Google Scholar. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) study presented original research, (2) article was written in English, (3) research participants were children between the ages of 0–18 years diagnosed with a FGID, and (4) research assessed family functioning, defined as “the social and structural properties of the global family environment” (Alderfer et al., 2008; Lewandowski et al., 2010). Based on initial review of titles and abstracts, 46 articles were selected for screening of the full text to determine whether inclusion criteria were met. Seventeen studies met inclusion criteria. See Figure 1 for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram with further details on study selection and inclusion.

Data Extraction

The following information was extracted and entered into an Excel spreadsheet by the first author and confirmed by the third author: country of origin, study design (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal), sample size and type (i.e., clinic- or community-based), child age range, FGID diagnosis, comparison group information (if applicable), family functioning measures and informants, child outcome measures (if applicable), and findings related to family functioning.

Quality Assessment Ratings

Two authors independently evaluated each study based on a set of previously developed scientific merit criteria (Alderfer et al., 2010). Studies were rated across nine domains (explicit scientific context and purpose, methods, measurement reliability and statistics, statistical power, internal validity, measurement validity and generalizability, external validity, discussion, and contribution to knowledge) on a 3-point scale (1 = poor quality, 2 = moderate quality, 3 = high quality). The scores were then averaged for a single total merit score and rounded to the nearest tenth. Interrater reliability was examined by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with a value greater than .75 indicating good reliability (Koo & Li, 2016). An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare study quality ratings between studies that reported significant findings and studies that reported nonsignificant findings. In addition, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to explore study quality differences between “older” (i.e., studies conducted prior to 2000; n = 9) and “recent” (i.e., studies conducted 2000 and after; n = 8) studies. A p-value of < .05 indicated significance.

Results

General Study Characteristics

The 17 included studies were conducted from 1982 to 2018, with majority of studies conducted in the United States (n = 9; 55%). Four studies were theses or dissertations (Mogilevsky, 1999; Roblin, 1999; Sieberg, 2009; Tighe, 1994). All studies were quantitative, with the majority being cross-sectional (n = 12). Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 328 children, with child age ranging from 3 to 18 years old. RAP (also known as FAP) was the most represented FGID (n = 12), followed by FC, including with and without encopresis and with and without fecal incontinence (n = 4), and then CVS (n = 1). Fifteen studies consisted of clinic-based samples (e.g., primary care clinics, specialty clinics) and two studies utilized both clinic- and community-based samples.

The majority of studies (n = 13) examined between-group differences in family functioning of youth with FGIDs and a comparison group. The remaining studies categorized children with FGIDs into distinct family functioning clusters/profiles or examined associations between family functioning and other study variables (e.g., child psychosocial functioning, sociodemographic factors, disease characteristics). Studies examining multiple relationships involving family functioning (e.g., group comparisons and sociodemographic and family functioning correlates) are discussed in the results twice.

Quality assessment ratings ranged from 1.8 to 2.6 (M = 2.3, SD = .26), with the average of studies demonstrating moderate quality. See Tables I and II for each study’s quality assessment rating. The most common areas of concern among the studies involved statistical power, generalizability of results, and minimal or unclear information about individual participant differences (e.g., age, race, disease factors) between comparison groups. Interrater reliability was excellent (ICC = .94; 95% CI: 0.80–0.98), and therefore, the first author’s ratings were used in the tables and analyses (i.e., t-test, ANOVA). Studies that reported significant findings had higher quality ratings (M = 2.3, SD = .25) than studies that reported nonsignificant findings (M = 2.1, SD = .17); t(15) = 2.26, p = .04. In addition, “older” studies had lower quality ratings (M = 2.13, SD = .14) than “recent” studies (M = 2.40, SD = .30); F(1, 15) = 5.65, p = .03.

General Study Characteristics, Quality Assessment Ratings, and Primary Findings of Studies Examining Group Differences (n = 13)

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | FGID . | Comparisongroup(s) . | Childagerange(years) . | Familyfunctioningmeasure;informant . | Qualityrating (1-3) . | Findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP)/Functional abdominal pain (FAP) | |||||||

| Ghanizadeh et al. (2008); Iran | Cross-sectional | FAP (n = 45) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 45); Healthy control (n = 45) | 5–18 | FAD; Not reported | 2.6 | A trend (p = .05) was found for children with RAP demonstrating more overall family dysfunction when compared to the other groups. Children with RAP scored higher (worse) in family roles when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Kaufman et al. (1997); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 24) | Organic bowel disease (n = 25); Healthy control (n = 19) | 12–16 | FES; Mother, child | 2.3 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with RAP and their mothers scored lower (worse) on various family functioning subscales when compared to a normative sample.* |

| Klooper (1982); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 15) | Leukemia (n = 15); Asthma (n = 15) | 6–13 | FACES; Mother, father, child | 2.2 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. The overall sample demonstrated elevated levels of rigidity and enmeshment when compared to a normative sample. |

| Liakopoulou-Kairis et al. (2002); Greece | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 38) | Headache (n = 31); Healthy control (n = 60) | 8–13 | FAD; Mother | 2.2 | Children with RAP scored higher (worse) on overall family functioning and various family functioning subscales when compared to the healthy control group.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children with headaches. |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | Normative sample | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | All families scored within normal ranges on the FES. |

| Sieberg (2009); USA | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 8) | Normative sample | 8–14 | FES; Parent, child | 1.8 | Most families demonstrated FES scores within the normal range. Small sample size and missing data made findings inconclusive. |

| Walker et al. (1993); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 88) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 57); Psychiatric diagnosis (n = 48); Healthy control (n = 56) | 6–18 | FRI; Child; FEQ; Mother | 2.3 | Families of children with RAP demonstrated better family relationships and less negative family affect when compared to families of children with psychiatric disorders.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children in the healthy control group. |

| Wasserman et al. (1988); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 31) | Healthy control (n = 31) | 6–16 | FES; Not reported | 2.2 | Family functioning did not differ between groups. A trend (p = .06) was found for children with RAP demonstrating less expressiveness when compared to healthy children. |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | Psychosomatic family functioning did not differ between families of children with RAP and families of children with Crohn’s disease. Families of children with RAP expressed more triangulation and marital dysfunction than families of children with ulcerative colitis.* |

| Functional constipation (FC) | |||||||

| Kovacic et al. (2015); USA | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 184) | FC + fecal incontinence (n = 226) | 2–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.6 | Overall family functioning and family relationships were worse in children with FC + fecal incontinence when compared to children with only FC.* Family daily activities did not differ between groups. |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | Normative sample | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Majority of families of children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) family roles and cohesion when compared to a normative sample. |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) overall family functioning, family relationships, and family daily activities when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Encopresis | |||||||

| Cengel-Kultur et al. (2014); Turkey | Cross-sectional | Encopresis with constipation (n = 30) | Encopresis without constipation (n = 11) | 6–16 | FAD; Mother | 2.6 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with encopresis with constipation demonstrated higher (worse) family roles and affective involvement when compared to children with encopresis without constipation.* |

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | FGID . | Comparisongroup(s) . | Childagerange(years) . | Familyfunctioningmeasure;informant . | Qualityrating (1-3) . | Findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP)/Functional abdominal pain (FAP) | |||||||

| Ghanizadeh et al. (2008); Iran | Cross-sectional | FAP (n = 45) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 45); Healthy control (n = 45) | 5–18 | FAD; Not reported | 2.6 | A trend (p = .05) was found for children with RAP demonstrating more overall family dysfunction when compared to the other groups. Children with RAP scored higher (worse) in family roles when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Kaufman et al. (1997); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 24) | Organic bowel disease (n = 25); Healthy control (n = 19) | 12–16 | FES; Mother, child | 2.3 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with RAP and their mothers scored lower (worse) on various family functioning subscales when compared to a normative sample.* |

| Klooper (1982); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 15) | Leukemia (n = 15); Asthma (n = 15) | 6–13 | FACES; Mother, father, child | 2.2 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. The overall sample demonstrated elevated levels of rigidity and enmeshment when compared to a normative sample. |

| Liakopoulou-Kairis et al. (2002); Greece | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 38) | Headache (n = 31); Healthy control (n = 60) | 8–13 | FAD; Mother | 2.2 | Children with RAP scored higher (worse) on overall family functioning and various family functioning subscales when compared to the healthy control group.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children with headaches. |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | Normative sample | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | All families scored within normal ranges on the FES. |

| Sieberg (2009); USA | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 8) | Normative sample | 8–14 | FES; Parent, child | 1.8 | Most families demonstrated FES scores within the normal range. Small sample size and missing data made findings inconclusive. |

| Walker et al. (1993); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 88) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 57); Psychiatric diagnosis (n = 48); Healthy control (n = 56) | 6–18 | FRI; Child; FEQ; Mother | 2.3 | Families of children with RAP demonstrated better family relationships and less negative family affect when compared to families of children with psychiatric disorders.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children in the healthy control group. |

| Wasserman et al. (1988); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 31) | Healthy control (n = 31) | 6–16 | FES; Not reported | 2.2 | Family functioning did not differ between groups. A trend (p = .06) was found for children with RAP demonstrating less expressiveness when compared to healthy children. |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | Psychosomatic family functioning did not differ between families of children with RAP and families of children with Crohn’s disease. Families of children with RAP expressed more triangulation and marital dysfunction than families of children with ulcerative colitis.* |

| Functional constipation (FC) | |||||||

| Kovacic et al. (2015); USA | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 184) | FC + fecal incontinence (n = 226) | 2–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.6 | Overall family functioning and family relationships were worse in children with FC + fecal incontinence when compared to children with only FC.* Family daily activities did not differ between groups. |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | Normative sample | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Majority of families of children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) family roles and cohesion when compared to a normative sample. |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) overall family functioning, family relationships, and family daily activities when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Encopresis | |||||||

| Cengel-Kultur et al. (2014); Turkey | Cross-sectional | Encopresis with constipation (n = 30) | Encopresis without constipation (n = 11) | 6–16 | FAD; Mother | 2.6 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with encopresis with constipation demonstrated higher (worse) family roles and affective involvement when compared to children with encopresis without constipation.* |

Note. CI-PSI = Chronic Illness Psychosocial Inventory; FACES = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; FEQ = Family Expressiveness Questionnaire; FES = Family Environment Scale; FRI = Family Relationship Index; PedsQL FIM = Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module.

Indicates significance (p < .05).

General Study Characteristics, Quality Assessment Ratings, and Primary Findings of Studies Examining Group Differences (n = 13)

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | FGID . | Comparisongroup(s) . | Childagerange(years) . | Familyfunctioningmeasure;informant . | Qualityrating (1-3) . | Findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP)/Functional abdominal pain (FAP) | |||||||

| Ghanizadeh et al. (2008); Iran | Cross-sectional | FAP (n = 45) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 45); Healthy control (n = 45) | 5–18 | FAD; Not reported | 2.6 | A trend (p = .05) was found for children with RAP demonstrating more overall family dysfunction when compared to the other groups. Children with RAP scored higher (worse) in family roles when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Kaufman et al. (1997); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 24) | Organic bowel disease (n = 25); Healthy control (n = 19) | 12–16 | FES; Mother, child | 2.3 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with RAP and their mothers scored lower (worse) on various family functioning subscales when compared to a normative sample.* |

| Klooper (1982); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 15) | Leukemia (n = 15); Asthma (n = 15) | 6–13 | FACES; Mother, father, child | 2.2 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. The overall sample demonstrated elevated levels of rigidity and enmeshment when compared to a normative sample. |

| Liakopoulou-Kairis et al. (2002); Greece | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 38) | Headache (n = 31); Healthy control (n = 60) | 8–13 | FAD; Mother | 2.2 | Children with RAP scored higher (worse) on overall family functioning and various family functioning subscales when compared to the healthy control group.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children with headaches. |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | Normative sample | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | All families scored within normal ranges on the FES. |

| Sieberg (2009); USA | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 8) | Normative sample | 8–14 | FES; Parent, child | 1.8 | Most families demonstrated FES scores within the normal range. Small sample size and missing data made findings inconclusive. |

| Walker et al. (1993); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 88) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 57); Psychiatric diagnosis (n = 48); Healthy control (n = 56) | 6–18 | FRI; Child; FEQ; Mother | 2.3 | Families of children with RAP demonstrated better family relationships and less negative family affect when compared to families of children with psychiatric disorders.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children in the healthy control group. |

| Wasserman et al. (1988); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 31) | Healthy control (n = 31) | 6–16 | FES; Not reported | 2.2 | Family functioning did not differ between groups. A trend (p = .06) was found for children with RAP demonstrating less expressiveness when compared to healthy children. |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | Psychosomatic family functioning did not differ between families of children with RAP and families of children with Crohn’s disease. Families of children with RAP expressed more triangulation and marital dysfunction than families of children with ulcerative colitis.* |

| Functional constipation (FC) | |||||||

| Kovacic et al. (2015); USA | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 184) | FC + fecal incontinence (n = 226) | 2–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.6 | Overall family functioning and family relationships were worse in children with FC + fecal incontinence when compared to children with only FC.* Family daily activities did not differ between groups. |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | Normative sample | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Majority of families of children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) family roles and cohesion when compared to a normative sample. |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) overall family functioning, family relationships, and family daily activities when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Encopresis | |||||||

| Cengel-Kultur et al. (2014); Turkey | Cross-sectional | Encopresis with constipation (n = 30) | Encopresis without constipation (n = 11) | 6–16 | FAD; Mother | 2.6 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with encopresis with constipation demonstrated higher (worse) family roles and affective involvement when compared to children with encopresis without constipation.* |

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | FGID . | Comparisongroup(s) . | Childagerange(years) . | Familyfunctioningmeasure;informant . | Qualityrating (1-3) . | Findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP)/Functional abdominal pain (FAP) | |||||||

| Ghanizadeh et al. (2008); Iran | Cross-sectional | FAP (n = 45) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 45); Healthy control (n = 45) | 5–18 | FAD; Not reported | 2.6 | A trend (p = .05) was found for children with RAP demonstrating more overall family dysfunction when compared to the other groups. Children with RAP scored higher (worse) in family roles when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Kaufman et al. (1997); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 24) | Organic bowel disease (n = 25); Healthy control (n = 19) | 12–16 | FES; Mother, child | 2.3 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with RAP and their mothers scored lower (worse) on various family functioning subscales when compared to a normative sample.* |

| Klooper (1982); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 15) | Leukemia (n = 15); Asthma (n = 15) | 6–13 | FACES; Mother, father, child | 2.2 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. The overall sample demonstrated elevated levels of rigidity and enmeshment when compared to a normative sample. |

| Liakopoulou-Kairis et al. (2002); Greece | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 38) | Headache (n = 31); Healthy control (n = 60) | 8–13 | FAD; Mother | 2.2 | Children with RAP scored higher (worse) on overall family functioning and various family functioning subscales when compared to the healthy control group.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children with headaches. |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | Normative sample | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | All families scored within normal ranges on the FES. |

| Sieberg (2009); USA | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 8) | Normative sample | 8–14 | FES; Parent, child | 1.8 | Most families demonstrated FES scores within the normal range. Small sample size and missing data made findings inconclusive. |

| Walker et al. (1993); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 88) | Peptic ulcer disease (n = 57); Psychiatric diagnosis (n = 48); Healthy control (n = 56) | 6–18 | FRI; Child; FEQ; Mother | 2.3 | Families of children with RAP demonstrated better family relationships and less negative family affect when compared to families of children with psychiatric disorders.* Family functioning did not differ between children with RAP and children in the healthy control group. |

| Wasserman et al. (1988); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 31) | Healthy control (n = 31) | 6–16 | FES; Not reported | 2.2 | Family functioning did not differ between groups. A trend (p = .06) was found for children with RAP demonstrating less expressiveness when compared to healthy children. |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | Psychosomatic family functioning did not differ between families of children with RAP and families of children with Crohn’s disease. Families of children with RAP expressed more triangulation and marital dysfunction than families of children with ulcerative colitis.* |

| Functional constipation (FC) | |||||||

| Kovacic et al. (2015); USA | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 184) | FC + fecal incontinence (n = 226) | 2–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.6 | Overall family functioning and family relationships were worse in children with FC + fecal incontinence when compared to children with only FC.* Family daily activities did not differ between groups. |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | Normative sample | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Majority of families of children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) family roles and cohesion when compared to a normative sample. |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Children with FC demonstrated lower (worse) overall family functioning, family relationships, and family daily activities when compared to the healthy control group.* |

| Encopresis | |||||||

| Cengel-Kultur et al. (2014); Turkey | Cross-sectional | Encopresis with constipation (n = 30) | Encopresis without constipation (n = 11) | 6–16 | FAD; Mother | 2.6 | Overall family functioning did not differ between groups. Children with encopresis with constipation demonstrated higher (worse) family roles and affective involvement when compared to children with encopresis without constipation.* |

Note. CI-PSI = Chronic Illness Psychosocial Inventory; FACES = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; FEQ = Family Expressiveness Questionnaire; FES = Family Environment Scale; FRI = Family Relationship Index; PedsQL FIM = Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module.

Indicates significance (p < .05).

General Study Characteristics, Quality Assessment Ratings, and Findings of Studies Examining Family Functioning Correlates (n = 8)

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | Sampleparticipants . | Comparisongroup . | Child age range (years) . | Family functioning measure; informant . | Quality rating (1–3) . | Findings . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logan & Scharff (2005); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 30) | Headache (n = 48) | 7–17 | FES; Mother | 2.6 | Family conflict, organization, and independence predicted functional disability in the overall sample.* Overall family environment moderated the relationship between pain and functional disability among children with headaches but not for children with RAP. Larger family size was associated with higher levels of family control in the overall sample.* | |

| Mogilevsky (1999); Canada | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 60) | – | 6–16 | FRI; Caregiver, child | 2 | A family dysfunction cluster was identified for 25% of children. Family functioning was related to child depression, anxiety, somatization, self-concept, and pain modeling* but not pain reinforcement. | |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | – | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Parent marital status and child disease characteristics (duration, anal fissures, and enuresis) were associated with various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | – | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | No relationship between family functioning and pain intensity and frequency were found. | |

| Tighe (1994); UK | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 48) | Appendicitis (n = 35) | 5–15 | FRT; Child | 1.9 | A Family Dynamics cluster was not supported for either group. Children with RAP displayed elevated levels of family enmeshment when child age was not controlled for.* | |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Sociodemographic factors (child age, caregiver education, family SES), disease characteristics (duration, defecation, pain), and child health-related quality of life uniquely related to various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Wang-hall et al. (2018); USA | Cross-sectional | CVS (N = 42) | – | 8–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.2 | More child anxiety and missed school days due to CVS predicted overall family functioning. Child anxiety was negatively associated with family daily activities.* | |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | No relationship was found between psychosomatic family functioning and disease chronicity and child psychosocial functioning. | |

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | Sampleparticipants . | Comparisongroup . | Child age range (years) . | Family functioning measure; informant . | Quality rating (1–3) . | Findings . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logan & Scharff (2005); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 30) | Headache (n = 48) | 7–17 | FES; Mother | 2.6 | Family conflict, organization, and independence predicted functional disability in the overall sample.* Overall family environment moderated the relationship between pain and functional disability among children with headaches but not for children with RAP. Larger family size was associated with higher levels of family control in the overall sample.* | |

| Mogilevsky (1999); Canada | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 60) | – | 6–16 | FRI; Caregiver, child | 2 | A family dysfunction cluster was identified for 25% of children. Family functioning was related to child depression, anxiety, somatization, self-concept, and pain modeling* but not pain reinforcement. | |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | – | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Parent marital status and child disease characteristics (duration, anal fissures, and enuresis) were associated with various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | – | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | No relationship between family functioning and pain intensity and frequency were found. | |

| Tighe (1994); UK | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 48) | Appendicitis (n = 35) | 5–15 | FRT; Child | 1.9 | A Family Dynamics cluster was not supported for either group. Children with RAP displayed elevated levels of family enmeshment when child age was not controlled for.* | |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Sociodemographic factors (child age, caregiver education, family SES), disease characteristics (duration, defecation, pain), and child health-related quality of life uniquely related to various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Wang-hall et al. (2018); USA | Cross-sectional | CVS (N = 42) | – | 8–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.2 | More child anxiety and missed school days due to CVS predicted overall family functioning. Child anxiety was negatively associated with family daily activities.* | |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | No relationship was found between psychosomatic family functioning and disease chronicity and child psychosocial functioning. | |

Note. CI-PSI = Chronic Illness Psychosocial Inventory; CVS = cyclic vomiting syndrome; FACES = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; FC = functional constipation; FES = Family Environment Scale; FRI = Family Relationship Index; FRT = Family Relations Test; PedsQL FIM = Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module; RAP = recurrent abdominal pain.

Significance (p < .05).

General Study Characteristics, Quality Assessment Ratings, and Findings of Studies Examining Family Functioning Correlates (n = 8)

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | Sampleparticipants . | Comparisongroup . | Child age range (years) . | Family functioning measure; informant . | Quality rating (1–3) . | Findings . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logan & Scharff (2005); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 30) | Headache (n = 48) | 7–17 | FES; Mother | 2.6 | Family conflict, organization, and independence predicted functional disability in the overall sample.* Overall family environment moderated the relationship between pain and functional disability among children with headaches but not for children with RAP. Larger family size was associated with higher levels of family control in the overall sample.* | |

| Mogilevsky (1999); Canada | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 60) | – | 6–16 | FRI; Caregiver, child | 2 | A family dysfunction cluster was identified for 25% of children. Family functioning was related to child depression, anxiety, somatization, self-concept, and pain modeling* but not pain reinforcement. | |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | – | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Parent marital status and child disease characteristics (duration, anal fissures, and enuresis) were associated with various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | – | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | No relationship between family functioning and pain intensity and frequency were found. | |

| Tighe (1994); UK | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 48) | Appendicitis (n = 35) | 5–15 | FRT; Child | 1.9 | A Family Dynamics cluster was not supported for either group. Children with RAP displayed elevated levels of family enmeshment when child age was not controlled for.* | |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Sociodemographic factors (child age, caregiver education, family SES), disease characteristics (duration, defecation, pain), and child health-related quality of life uniquely related to various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Wang-hall et al. (2018); USA | Cross-sectional | CVS (N = 42) | – | 8–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.2 | More child anxiety and missed school days due to CVS predicted overall family functioning. Child anxiety was negatively associated with family daily activities.* | |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | No relationship was found between psychosomatic family functioning and disease chronicity and child psychosocial functioning. | |

| Author(s) (Year); Origin . | Design . | Sampleparticipants . | Comparisongroup . | Child age range (years) . | Family functioning measure; informant . | Quality rating (1–3) . | Findings . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logan & Scharff (2005); USA | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 30) | Headache (n = 48) | 7–17 | FES; Mother | 2.6 | Family conflict, organization, and independence predicted functional disability in the overall sample.* Overall family environment moderated the relationship between pain and functional disability among children with headaches but not for children with RAP. Larger family size was associated with higher levels of family control in the overall sample.* | |

| Mogilevsky (1999); Canada | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 60) | – | 6–16 | FRI; Caregiver, child | 2 | A family dysfunction cluster was identified for 25% of children. Family functioning was related to child depression, anxiety, somatization, self-concept, and pain modeling* but not pain reinforcement. | |

| Roblin (1999); Canada | Longitudinal; RCT | FC (with and without encopresis) (n = 40) | – | 3–15 | FAD, CI-PSI; Mother, father, child | 2.1 | Parent marital status and child disease characteristics (duration, anal fissures, and enuresis) were associated with various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Sanders et al. (1990); Australia | Longitudinal; RCT | RAP (n = 16) | – | 6–12 | FES; Mother, father, child | 2 | No relationship between family functioning and pain intensity and frequency were found. | |

| Tighe (1994); UK | Cross-sectional | RAP (n = 48) | Appendicitis (n = 35) | 5–15 | FRT; Child | 1.9 | A Family Dynamics cluster was not supported for either group. Children with RAP displayed elevated levels of family enmeshment when child age was not controlled for.* | |

| Wang et al. (2013); China | Cross-sectional | FC (n = 152) | Healthy control (n = 176) | 3–6 | PedsQL FIM; Caregiver | 2.6 | Sociodemographic factors (child age, caregiver education, family SES), disease characteristics (duration, defecation, pain), and child health-related quality of life uniquely related to various family functioning subscales.* | |

| Wang-hall et al. (2018); USA | Cross-sectional | CVS (N = 42) | – | 8–18 | PedsQL FIM; Parent | 2.2 | More child anxiety and missed school days due to CVS predicted overall family functioning. Child anxiety was negatively associated with family daily activities.* | |

| Wood et al. (1989); USA | Longitudinal | RAP (n = 11) | Crohn’s disease (n = 18); Ulcerative colitis (n = 11) | 11–16 | Interaction tasks; Observation | 2.2 | No relationship was found between psychosomatic family functioning and disease chronicity and child psychosocial functioning. | |

Note. CI-PSI = Chronic Illness Psychosocial Inventory; CVS = cyclic vomiting syndrome; FACES = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; FC = functional constipation; FES = Family Environment Scale; FRI = Family Relationship Index; FRT = Family Relations Test; PedsQL FIM = Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module; RAP = recurrent abdominal pain.

Significance (p < .05).

Most studies used standardized questionnaires to assess family functioning (Family Environment Scale, n = 5; Family Assessment Device, n = 4; Pediatric Quality of Life Family Impact Module, n = 3; Family Relationship Index, n = 2; Family Expressiveness Questionnaire, n = 1; Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale, n = 1; Chronic Illness Psychosocial Inventory, n = 1). One study used observational methods (i.e., interaction and discussion tasks; Wood et al., 1989) and another study used a projective test (i.e., Bene Anthony Family Relations Test; Tighe, 1994). Some studies assessed general family functioning (i.e., a global or overall score), while others measured specific facets of family functioning (e.g., cohesion, conflict, roles). Two studies used multiple measures to assess family functioning (Roblin, 1999; Walker et al., 1993).

Group Differences in Family Functioning

Nine studies examined group differences in family functioning of children with RAP, with the majority of findings (i.e., 5 of the 9 studies; 55%) suggesting that families of children with RAP experience family functioning difficulties. The majority of these differences emerged within specific facets of family functioning (e.g., expressiveness, roles) rather than overall or global family functioning (Ghanizadeh et al., 2008; Kaufman et al., 1997; Wood et al., 1989). Differences were also more common when children with RAP were compared to healthy youth or normative samples rather than other pediatric populations (Kaufman et al., 1997; Klooper, 1982; Liakopoulou-Kairis et al., 2002). The remaining four studies suggested that families of children with RAP demonstrated family functioning within normal ranges (Sanders et al., 1990; Sieberg, 2009; Walker et al., 1993; Wasserman et al., 1988).

Four studies examined group differences in family functioning of children with FGIDs involving constipation (e.g., FC, encopresis with constipation) and found that families of children with constipation exhibit family functioning difficulties. Two studies found this relationship in overall family functioning (Kovacic et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2013), while the other two studies found this relationship in specific family functioning domains (e.g., roles, cohesion; Cengel-Kultur et al., 2014; Roblin, 1999). Two studies found children with FC displayed lower (worse) family functioning when compared to a healthy control group or a normative sample (Roblin, 1999; Wang et al., 2013), and the other two studies found children with more severe FGID symptoms (e.g., children with encopresis with constipation) displayed worse family functioning when compared to children with less severe FGID symptoms (e.g., children with encopresis without constipation; Cengel-Kultur et al., 2014; Kovacic et al., 2015). See Table I for a summary of methodology and primary findings of the 13 studies examining group differences.

Family Functioning Profiles

Using cluster analyses, Mogilevsky (1999) identified a “Family Dysfunction” cluster among 25% of children with RAP. Specifically, these children demonstrated lower family cohesion and expressiveness and higher conflict when compared to children in the other clusters. Tighe (1994) did not find support for a “Family Dynamics” cluster among children with RAP when using discriminant analyses, as there were no family functioning differences among children with RAP and children with appendicitis.

Family Functioning Correlates

Three studies reported on the relationship between sociodemographic factors and family functioning among children with FGIDs. Younger child age and parent divorce were related to lower (worse) family functioning domains (Roblin, 1999; Wang et al., 2013). Larger family size was related to higher levels of family control (Logan & Scharff, 2005). Higher caregiver education and higher family socioeconomic status (SES) were related to higher (better) family functioning (Wang et al., 2013).

Seven studies examined the relationship between disease characteristics, functional disability, or pain and family functioning, with the majority (i.e., 5 out of 7; 71%) reporting significant relationships. Longer disease duration, more frequent FGID episodes and symptoms, and worse disease severity were associated with lower (worse) family functioning (Roblin, 1999; Wang et al., 2013; Wang-hall et al., 2018). Worse family functioning also predicted more functional disability in a combined sample of children with RAP and headaches (Logan & Scharff, 2005). Lastly, the presence of parent pain modeling was negatively related to family functioning (Mogilevsky, 1999). Wood et al. (1989) and Sanders et al. (1990) did not find support for the relationship between family functioning and disease chronicity or pain intensity and frequency, respectively.

Four studies explored the association between family functioning and child psychosocial functioning. Child anxiety, depression, and somatization were negatively related to family functioning (Mogilevsky, 1999; Wang-hall et al., 2018), whereas better child health-related quality of life and a positive child self-concept were positively related to family functioning (Mogilevsky, 1999; Wang et al., 2013). However, Wood et al. (1989) did not find a relationship between family functioning and child psychosocial functioning. See Table II for a summary of methodology and primary findings of the 8 studies examining family functioning correlates.

Discussion

The current review synthesized the findings of 17 studies examining family functioning among children with FGIDs. The majority of studies demonstrated family functioning difficulties among children with FGIDs when compared to healthy counterparts. These findings highlight that some families of children with FGIDs experience family functioning challenges, confirming the importance of integrating a family systems approach into the conceptualization and treatment efforts of pediatric FGIDs (Kazak et al., 2002; Palermo et al., 2014). The remaining studies found unique relationships between psychosocial functioning (e.g., depression, anxiety), disease characteristics (e.g., duration, severity), sociodemographic factors (e.g., child age, parent marital status) and family functioning among youth with FGIDs.

Although significant group differences in family functioning emerged, these differences were more consistent when children with FGIDs were compared to control groups or normative populations, as opposed to being compared to other pediatric populations. For example, some studies (e.g., Kaufman et al., 1997; Klooper, 1982; Liakopoulou-Kairis et al., 2002) did not find significant family functioning differences among children with FGIDs and children with other health conditions (e.g., cancer, asthma, headaches), but did find significant differences when comparing children with FGIDs to healthy youth or normative samples. This may suggest that families of children with health conditions, regardless of disease, face similar challenges such as adapting to a new lifestyle occupied with medical visits and daily life disruptions, coping with illness uncertainty, and fulfilling new family role expectations. Therefore, difficulties in family functioning may not be disease-specific and may even be adaptive to successfully adjust to having a child with a health condition (Alderfer et al., 2008). This is consistent with findings from Herzer et al. (2010) who identified no significant differences in family functioning across five pediatric populations (i.e., cystic fibrosis, obesity, sickle cell disease, inflammatory bowel disease, epilepsy). Therefore, family-based treatment approaches (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem-solving) that have been effective in improving family functioning and child outcomes in other pediatric populations (Law et al., 2014) may also be effective for pediatric FGID families experiencing maladaptive family functioning.

Differences in family functioning were also more consistent among specific domains of family functioning rather than overall family functioning. Prior research has found similar results in other pediatric populations (e.g., epilepsy, obesity) where family functioning domains such as communication, roles, and affective involvement appear to be challenging for families (Herzer et al., 2010; Lewandowski et al., 2010). It may be that specific facets of family functioning are uniquely difficult to maintain for families of children with chronic health conditions, including families of children with FGIDs. For example, two studies found that children with FGIDs had significantly worse family roles when compared to other groups (Cengel-Kultur et al., 2014; Ghanizadeh et al., 2008). Unpredictable GI episodes and symptoms may require family members to be flexible and adapt quickly to the current situation (Herzer et al., 2010). For example, if a child has to be picked up from school due to GI symptoms, caregivers must negotiate who is going to leave work and stay home with the child. This constant, unpredictable shift in roles may create distress for specific family members and dysfunction within the family system.

Three out of four studies that examined family functioning and child psychosocial functioning found that child anxiety (Mogilevsky 1999; Wang-hall et al., 2018), depression (Mogilevsky 1999), somatization (Mogilevsky 1999), self-concept (Mogilevsky 1999), and health-related quality of life (Wang et al., 2013) were related to family functioning among children with FGIDs. These findings are consistent with research in other pediatric populations (e.g., asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes), where family functioning difficulties are associated with child psychosocial functioning (e.g., internalizing symptoms, quality of life, behavior problems; Gray et al., 2013; Leeman et al., 2016; Sawyer et al., 2000). Considering the biopsychosocial influences of FGIDs (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016), it is critical to identify and treat children with psychosocial and family functioning difficulties, as these difficulties may maintain or exacerbate GI symptoms and decrease child quality of life.

A number of sociodemographic factors and disease characteristics were associated with family functioning. Younger child age, longer duration of constipation, painful defecation, abdominal pain, anal fissures, and missed school because of GI symptoms were related to worse family functioning (Roblin, 1999; Wang et al., 2013; Wang-hall et al, 2018), whereas higher family SES, higher caregiver education, and more frequent defecation (Wang et al., 2013) were associated with better family functioning among children with FGIDs. This line of research is critical in order to identify children and families that may be at risk for poorer outcomes and need to be targeted for treatment.

Future Research Recommendations

Although majority of studies were of moderate quality, there are opportunities for improvement. Some family functioning measures used in the included studies were unvalidated or demonstrated questionable psychometric properties (e.g., CI-PSI, FRT). Implementing well-established, comprehensive family functioning measures should be a priority for future research in order to capture the unique experiences families of children with FGIDs encounter. Most of the included studies were descriptive, with only a few studies undertaking the challenge of examining the directionality between family functioning and child functioning (e.g., Logan & Scharff, 2005; Wang et al., 2013; Wang-hall et al., 2018). Future studies should aim to better understand the directionality of these associations in order to help identity children at risk for poorer outcomes and to inform psychologists where to intervene to improve treatment efforts (i.e., individual-level vs. family-level).

Majority of studies utilized a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to draw temporal conclusions. Understanding if family functioning changes over time in families of children with FGIDs could aid in treatment efforts. For example, if families demonstrate unhealthy functioning at the child’s initial diagnosis but return to healthy functioning a few months or a year after diagnosis, psychologists could provide additional services and support during the initial months of the child’s diagnosis. This relationship has been demonstrated in other pediatric populations (e.g., diabetes, cancer; Northam et al., 1996; Pai et al., 2007). Therefore, longitudinal designs are warranted in order to investigate how family functioning may change over the trajectory of a child’s diagnosis or development. Approximately half of studies (47%) did not incorporate a theoretical framework or state hypotheses, hindering the integration of science and practice. Future research should implement theory-driven work in order to inform the understanding of FGIDs and improve the gap between research and practice.

Research should also strive to be more representative of the FGIDs that exist. Across 17 studies, only 3 pediatric FGIDs were examined, leaving a significant amount of disorders understudied. Pediatric FGIDs vary greatly in symptomatology (e.g., abdominal pain, regurgitation, fecal incontinence) and may have different effects on family functioning. A significant portion of the included studies consisted of clinic-based samples and a single informant. Since family functioning is multifaceted, it may differ based on the informant (e.g., father, grandparent; Kumpfer et al., 2016). The inclusion of community-based samples and multiple informants in future research would increase generalizability. There is also a great need for recent, updated research in this area, as only four studies were published within the past decade. Our understanding of FGIDs has significantly increased over the years (e.g., updated diagnostic guidelines, improved operationalization) and incorporating this newfound knowledge into FGID research would increase internal validity (Hyams et al., 2016). Furthermore, how families communicate and interact has likely changed across time. For example, parents may be more accommodating and reinforcing of their child’s symptoms than in previous decades (Levy et al., 2004; van Tilburg et al., 2015), which would influence the conceptualization of family functioning and what constitutes as “healthy” and “unhealthy” functioning.

Lastly, a greater focus on the influence of culture is needed when examining family functioning and pediatric FGIDs. The majority of the studies in the current review used family functioning measures validated on samples with minimal diversity in regard to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and family composition (Alderfer et al., 2008). Conceptualizations of “normative” and “healthy” family functioning are socially constructed and often differ based on one’s cultural background and individual differences (Francisconi et al., 2016). For example, a single-parent household may expect their child to have a more autonomous role in their disease management than a two-parent household. Similarly, communication styles, relationship and role expectations, and emotional responses differ between cultures and may lead families with diverse backgrounds to score within “unhealthy” ranges on measures validated primarily on white, middle-class, two-parent families (Alderfer et al., 2008; Chung & Gale, 2009). Furthermore, perceived legitimacy and severity of functional disorders vary by culture (Drossman, 2005), and these attitudes and beliefs may influence disease presentation and FGID treatment (Chuah & Mahadeva, 2018; Francisconi et al., 2016). Future research should strive to use culturally informed family functioning definitions and assessments to capture the unique influences of culture on family functioning and FGIDs.

Limitations of the Current Review

Although the current review demonstrates strengths such as reviewing the literature in a systematic and standardized way, utilizing a theoretical framework (i.e., family systems approach), and including multiple pediatric FGIDs, several limitations exist. First, although reflective of the current literature, inclusion of only 17 studies limits generalizability. Second, to be included in the study, search terms (i.e., FGID, pediatric, family functioning) had to be present in the title or abstract, which may have eliminated studies that examined these topics as secondary or exploratory aims. Third, the current review’s inclusion criterion of a FGID diagnosis excluded studies that consisted of children with FGID symptomatology or somatic symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain) but lacked a formal diagnosis. Families of children exhibiting FGID symptoms may differ in family functioning compared to families of children with a diagnosed FGID. Similarly, some studies may have used different language than the Rome Foundation (what our FGID search terms were based on) to describe their FGID sample and therefore, may not have been identified during the study search process.

In addition, the operationalization of family functioning used in the current review excluded parenting behaviors/practcies, which is sometimes included in other descriptions of family functioning (e.g., Cousino et al., 2017; Mikolajczak et al., 2018). Similarly, if studies used unconventional terms to describe family functioning, they may not have been captured in the search process. Fifth, as with any review, bias is important to consider. Findings from published articles may differ from findings from unpublished articles, as articles reporting significant findings are more likely to obtain publication compared to studies reporting null findings (Higgins & Green, 2008). Family functioning was also not always the primary outcome assessed in some of the included studies, which may have led to selective outcome reporting. Lastly, a meta-analysis was not conducted due to the significant variability in study methodology and outcomes assessed. A meta-analysis would have provided an opportunity to draw a larger conclusion across studies.

Clinical Implications

The findings from the current review indicate that some families of children with FGIDs demonstrate family functioning difficulties, suggesting that family functioning is an important factor to consider in the treatment of pediatric FGIDs. Family functioning difficulties may be leading to the maintenance or exacerbation of their child’s GI symptoms and functional disability (Logan & Scharff, 2005). To identify difficulties, a brief family functioning measure (e.g., Family Relationships Index, PedsQL Family Impact Module) should be incorporated into standard GI clinic procedures. To increase efficiency, families could complete the measure in the waiting room along with other standard clinic paperwork. In addition, assessing family functioning could be used to tailor treatment components to focus on the specific needs of the family (e.g., effective communication, clear role expectations).

To improve child and family functioning in pediatric health conditions, family systems theories suggest targeting family factors such as problem-solving, communication, and interaction patterns (Law et al., 2014; Person & Keefer, 2019), and the current study’s findings support this recommendation. Specifically, cognitive-behavioral family therapy and parental communication training (Palermo et al., 2009; Robins et al., 2005) have been linked to reducing pain, symptom severity, and functional disability in children with FGIDs (Duarte et al., 2006; Levy et al., 2010). Providing psychoeducation about the biopsychosocial influences of FGIDs to families should also be a priority, as this allows families to understand and identify modifiable factors that are influencing their child’s symptoms (Person & Keefer, 2019). This would also allow clinicians an opportunity to observe how the family communicates and interacts with one another and perceives the child’s symptoms (e.g., accepting, dismissive), which may inform future treatment recommendations and planning.

Lastly, in order to improve the integration of science and practice, collaboration should occur across institutions (e.g., specialty clinics, universities). Because the causal mechanisms of FGIDs remains unclear and effective treatments are still needed (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016), it is important that collaboration occurs across settings and disciplines to advance the understanding and treatment of FGIDs. Ideally, children with FGIDs should also be treated by a multidisciplinary team in order to best address the needs of the child and family (Nurko & Di Lorenzo, 2008).

Conclusions

Families of children with FGIDs demonstrated family functioning difficulties, particularly when compared to healthy counterparts and within specific facets of family functioning (e.g., roles, expressiveness). Findings also suggest that child psychosocial functioning, disease characteristics, and sociodemographic factors may be related to family functioning among youth with FGIDs. Although more research is needed to confirm these findings, the necessity of the involvement of families in pediatric FGID treatment should not be undermined. Future research should examine the relationship, with an emphasis on directionality, between family functioning and child physical and psychosocial functioning within a pediatric FGID context.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

Rome Foundation (