-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dennis C. Russo, Pioneers in Pediatric Psychology: Environments Shape Behavior, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 40, Issue 5, June 2015, Pages 487–491, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsv003

Close - Share Icon Share

Since my first immersion in the medical environment in 1975, I have had the opportunity to participate in and develop a number of different environments of care and types of services for children, adolescents, and their families. I am reminded that the famous philosopher Yogi Berra once said “You can observe a lot just by watching.” I continue to be impressed by the unique and ever-changing benefits to children’s health brought about by pediatric psychologists. I want to thank my colleagues for bestowing on me the opportunity to reflect on my personal experiences and the growth of our field.

When I arrived at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) to begin my undergraduate education, it was my career goal to become a physicist. However, my path changed very quickly. I was lucky to have had the opportunity to study with a number of outstanding psychologists. I can remember my first course in learning theory taught by David Premack, PhD, of Premack Principle fame. Simply put, the Premack Principle states that a more-preferred activity can be used to reinforce a less-preferred activity (Premack, 1959). Even though his original work was done with monkeys, its application to humans was apparent. In another of my classes, we watched the film “Behavior Modification: Teaching Language to Psychotic Children” (Lovaas, 1969). In essence, Dr Ivar Lovaas had applied his own learning research, the Premack Principle, and other findings from the basic research literature to develop a method to teach mute or echolalic autistic children how to speak and use language!

Signing With the Lovaas/Koegel Team

As I became more and more enmeshed in psychology, I became impressed with its potential to address the difficulties of our most seriously impaired children. At one point, impulsive undergraduate that I was, I drove the 90 miles to UCLA to sit and wait many hours at Dr Lovaas’ office only to be told he would be unable to see me that day. I returned to UCSB dejected but resolute to continue my studies of how learning and the principles of behavior could be applied for the clinical benefit of children.

Shortly thereafter, a wonderful opportunity appeared. I found out that Robert Koegel, PhD, a former student of Dr Lovaas’, had accepted a faculty position at UCSB. I was elated. I met with Dr Koegel on his arrival and began work as a volunteer in his efforts to create a school for autistic children and a formal educational curriculum. Within the first year, Dr Koegel announced that he and Dr Lovaas would establish a learning laboratory at the Children's Unit of Camarillo State Hospital where many children with autism could receive benefit.

Wednesday became the day of the week! We would head down from UCSB while Dr Lovaas and several of his students would come up from UCLA. Our work at UCLA, Camarillo, and UCSB branched out from basic studies of self-stimulation, self-injurious behavior, and stimulus overselectivity to developing classrooms, Teaching Homes, and the Early Intervention Project, which led to great improvements in the children’s language and social behavior through intensive early treatment. I learned that environments truly do shape behavior for both patients and therapists.

Welcome to the World of Pediatric Medicine

In late 1974, when I was deep in my dissertation, our laboratory had the opportunity to host Michael (Mike) Cataldo, PhD, then a senior graduate student of Dr Todd Risley at the University of Kansas (Figures 1–3). They had been doing remarkable work designing research-based therapeutic environments (Cataldo & Risley, 1974). Our dinner that evening was filled with ideas of how to integrate their work with that which we had already done in autism. That pleasant evening passed all too quickly.

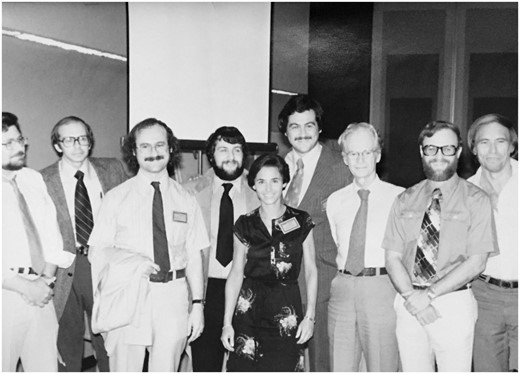

At the 1979 Annual Convention of the Association for Behavioral Analysis: From left to right: Todd Risley, PhD; Crighton (Buddy) Newsom, PhD; Edward (Ted) Carr, PhD; Arnold Rincover, PhD; Laura Schreibman, PhD; Dennis Russo, PhD; B.F. Skinner, PhD; Robert Koegel, PhD; and O. Ivar Lovaas, PhD.

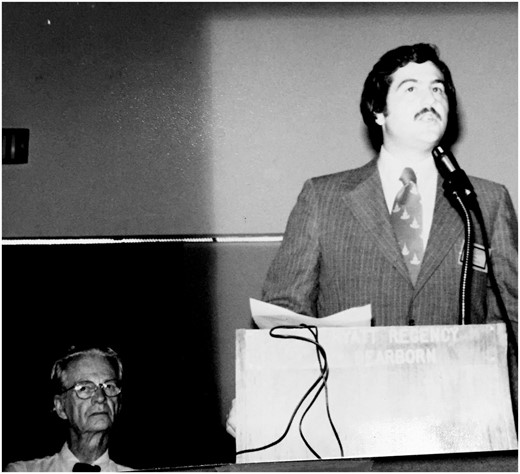

1979 Annual Convention of the Association for Behavioral Analysis: Dennis Russo, PhD, presenting with B.F. Skinner, PhD, in background.

In the spring of 1975, I had completed my doctoral work at UCSB. My plan at that point had been to remain at the UCSB Autism Program and Camarillo laboratory and continue to work on our projects. However, out of the blue, I received a call from Dr Cataldo. Mike told me he had just been offered the opportunity to develop a new program at the John F. Kennedy Institute for Handicapped Children and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, with the goal of creating a medical center/special pediatric hospital-based program for children with developmental disabilities. He asked if I would like to join him in this endeavor. I accepted the position as Associate Director of the Department of Behavioral Psychology at the John F. Kennedy Institute for Handicapped Children and arrived in Baltimore in September 1975 to begin my work there. It was a very exciting time and our program at Kennedy Institute grew rapidly. Right across the street was the Johns Hopkins Hospital where we held an appointment in psychiatry. This opened a new arena to us, supporting our development of inpatient consultation services.

My years at Kennedy and Hopkins, 1975 through 1979, occurred at a time of major transformation in medicine and psychology. Dr George Engel published his treatise on biopsychosocial care (Engel, 1977) and, at that time, the field was abuzz with a new understanding of health and illness. I was again fortunate enough to be in a new environment in which to apply pediatric psychology in the development of biopsychosocial treatment of children and adolescents with physical health and developmental issues.

The problems that we were working on in our clinics, less related to traditional mental health issues, contributed to a growing body of literature, which helped to define the role of the pediatric psychologist in health care. They were focused instead on defining the relationship between behavior and disease (Cataldo, Russo, Bird, & Varni, 1980), identifying new methods of assessment (Russo, Bird, & Masek, 1980), and developing behavioral treatments for medical problems such as lead poisoning (Madden, Russo, & Cataldo, 1980) and neurological disorders (Cataldo, Russo, & Freeman, 1980).

Off to Boston

My departure from Kennedy and Hopkins was the result of one of those rare, but pleasant, surprises that come along out of the blue as you are deeply engaged in your work. I received a call in 1979 from Leon Eisenberg, MD, and Donald Scherl, MD, at the Children's Hospital Medical Center of Boston and Harvard Medical School. They had become aware of the growth of pediatric psychology nationally and of our ongoing work in health and illness at the Kennedy/Hopkins program. Moreover, they were excited by its potential for contributions to general and specialty pediatric medicine. As a result of our discussions, I arrived in Boston in September 1979 to begin my role as Boston Children’s first Chief of Behavioral Psychology with a faculty appointment in Pediatrics and Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

I was joined, in my second year, by one of my postdoctoral students from Johns Hopkins, Bruce Masek, PhD. We worked to create a program of behavioral pediatric outpatient services and an inpatient consultation program serving the clinical needs of patients throughout the Children's Hospital of Boston. Partnerships quickly developed with the outpatient medical clinics to treat common issues such as feeding problems (Handen, Mandell, & Russo, 1986). Our inpatient work at Hopkins with the tertiary specialty medical services led to behavioral interventions for children with chronic and serious health problems such as renal transplant and dialysis (Russo, Bennett, Harmon, & Brown, 1981) and cystic fibrosis (Spirito, Russo, and Masek, 1984). We often worked with our medical colleagues across several environments. For example, our pain management program treated common ambulatory problems such as headaches (Mehegan, Masek, Harrison, Russo, & Leviton, 1987) and evaluated promising new technologies such as patient-controlled analgesia, post orthopedic surgery, using a method appropriate to children and adolescents (Berde et al., 1991).

Our group was renamed the Behavioral Medicine Program in 1981 in line with its broad contributions to health care in the institution. In 1982, our book, Behavioral Pediatrics: Research and Practice, was published (Russo & Varni, 1982), providing an early compilation of evidence supporting the efficacy of pediatric psychology treatments with a wide variety of diseases and disabilities.

In May 1983, I was honored to be invited to the National Working Conference on Education and Training in Health Psychology, sponsored by the recently developed APA Division 38, Health Psychology. A large group of behavioral scientists attended this conference, including several of us who were pediatric psychologists. The conference was held at the Arden House in Harriman, New York, representing a broad cross-section of developing work in health psychology with patients of all ages and all types of diseases or disabilities with a goal of defining the contribution and importance of health psychology in medicine and health (Stone, 1983). It was a time of unparalleled enthusiasm and growth for our new field. Even in those early years, all of us recognized the value of the inclusion of well-trained health psychologists across the spectrum of health and illness for patients of all ages and the importance of our contributions to the day-to-day practice of health care.

During that time, we were finding that other institutions, such as the U.S. Air Force, were very interested in pediatric psychology. We trained several postdoctoral fellows, at both Hopkins and Harvard, who returned to set up programs for families in the military. A number of us were “recruited” to travel to the Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center in San Antonio, the training hub for medicine in the Air Force, to train active duty air force psychologists in pediatric and health psychology, through their Distinguished Visiting Professor Program (DVP). Between 1982 and 1989, I made five visits as a DVP with my efforts focused on training air force psychologists in ambulatory and inpatient applications of pediatric psychology. Two of our air force fellows, upon return from their postdoctoral year with us, made particularly notable contributions to the growth of this important program: Col. Tommie Cayton, PhD, was seminal in starting the first DOD program in behavioral health psychology and Col. Karl O. “Skip” Moe, PhD, returned to work at the Uniform Services University of the Health Sciences developing a pathway for psychologists to participate on primary care teams.

Twenty-three years after my departure from Children’s and Harvard, in January 2012, I was invited to give Grand Rounds to the Department of Psychiatry at Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. It was wonderful to come home again. I was pleased that the seeds we had helped to plant at Children’s had developed into a beautiful bouquet! I was informed by my colleagues that Boston Children's Hospital had over 130 pediatric psychologists and pre-and postdoctoral students, who worked side-by-side with medical teams providing pediatric psychology services through the hospital and its ambulatory centers.

Bringing Services to Scale

In 1991, an opportunity developed to apply our pediatric and behavioral psychology methods on a large scale. Discussions of new models of care with Walter (Pete) Christian, PhD, a longtime colleague, who had become President and CEO of the May Institute, a private not-for-profit program on Cape Cod, led to new options to develop children’s services in community-based settings. Pete had a goal of developing this small school program for children with autism into a national network of services. Our initial discussions led to my joining the May Institute in 1991. This position combined my background in developmental disabilities and experience in pediatric and adult health care.

In my principal role as Chief Clinical Officer of the May Institute, we developed many programs growing from a small school on Cape Cod to an organization providing behavioral services and health care from coast-to-coast with a huge workforce with a $100+ million annual budget. Working with an outstanding group of colleagues, we developed programs and services covering the life span from preschool to geriatrics, and an APA Accredited Psychology Internship. Pediatric psychology was a prominent theme, as evidenced by a partnership with St Anne’s Hospital in Fall River, Massachusetts, where we created an early integrated care program, The Center for Children and Families, offering services for ambulatory care as well as patients presenting with complex chronic health and behavioral problems. Leaving the tertiary medical center and moving upstream into local hospitals and schools offered a great opportunity to provide community-based care to children, adolescents, and their families with the goal of prevention of more significant difficulties.

During my years at May Institute, I was honored to have been elected President of the Society of Pediatric Psychology in 1994 and to have received the Lee Salk Distinguished Service Award for Outstanding Contributions to Pediatric Psychology in 2001. In my Presidential Address, “The Long Road Home,” I discussed issues related to the growth and development of pediatric psychology and the importance of disseminating our science and practice beyond the tertiary medical center and into the community level.

It Takes a Family!

In February 2009, I was invited to present Keynote Address to the North Carolina Association for Behavior Analysis Conference in Wilmington, NC. As the meeting closed, Jeannie Golden, PhD, a Professor in the Psychology Department at East Carolina University (ECU), made me aware of new opportunities in North Carolina within the medical infrastructure and the community at large.

The Family Medicine Department at the Brody School of Medicine at ECU is focused on the training of family physicians. Consistently ranked as one of the top Medical Schools in the country for its placement of graduates into Family Practice, ECU was looking for a new faculty member to direct behavioral health and integrated care services. The program at the Brody School of Medicine, one of two Medical Schools of the University of North Carolina, is located in Greenville, North Carolina, in the rural eastern part of the state. Many adults suffer lifestyle disease such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity, often burdened by other factors including poverty and illiteracy. Many of our children are at significant risk for the same problems. There are few medical practices in rural North Carolina and little access to pediatric psychology or behavioral medicine services. I accepted the position as Head of Behavioral Medicine within the Department of Family Medicine and Clinical Professor of Family Medicine and Psychology at ECU in January 2010.

Patient-centered primary care is assuming an increasing role in today’s medical care. Behavior is a leading factor in the genesis and maintenance of disease and its management seen as critical in keeping people healthy and reducing costs. This new position presented a unique opportunity to improve the health of children and families, to address behavioral morbidity, and to develop real-time primary care services integrated with medical and behavioral health services in an academic medical center.

At ECU, I hold a joint appointment in both Family Medicine and Psychology. What a great opportunity for the simultaneous training of our doctoral students in our APA Accredited Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology and our medical students and residents, through the provision of Grand Rounds, academic teaching, video precepting, and, most importantly, through direct interaction between residents, psychology students, and faculty in actual patient encounters. Supported by a grant from the U.S. Health Services and Resources Administration, we have moved out of the therapy room onto the clinic floor. Patients are at the center of a health care team, which includes their physician, their nurses, our students, and faculty in the role of behavioral health consultants, pharmacists, and nutritionists, all focused on team-based health care.

I have, for many years, felt that improving the quality of care through closer on-site collaboration of physicians and psychologists in the primary care setting should be a priority in our health care system (Russo & Howard, 1999). These past 5 years have been extremely exciting and our program truly actualizes this integration, receiving significant support from both medicine and psychology. The literature documents the benefits of behavioral integration in primary care (O’Donohue et al., 2005; Robinson & Reiter, 2007). Recognizing this, the American Psychological Association has recently made a major commitment to the development of the role of psychologists in primary care naming pediatric psychologist, Doug Tynan, PhD, as its Director of Integrated Health Care.

Reflections on the Future of Pediatric Psychology

Integrated care is a place of future growth for pediatric psychology, promising exciting and important new roles for pediatric psychologists in direct patient care, improving health outcomes, and in the training of tomorrow’s physicians. We are beginning to better understand the complex needs of patients, addressing disease prevention and management, and supporting the centrality of families in health and illness.

I am reminded of my recognition, decades ago, of the importance of the work of pediatric psychologist, Carolyn Schroeder, PhD, and her colleagues in the primary care pediatric practice environment (Schroeder & Gordon, 2002). They introduced us to the idea of pediatric psychologists working side-by-side with the pediatrician to identify the health and behavioral needs of children and assisting families to implement care in the home environment. Carolyn, and her colleagues, had it right. Those of us who work today in medicine can testify to the value of family support and treating problems early. The focus of our physician colleagues on prevention and early assessment often allows pediatric psychologists to provide early care by identifying and treating problems before they become serious. Increasing effort to provide family access to pediatric psychology in the pediatrician or family doctor’s office will make a great impact in the quality of life that our children will have.

It is interesting to note that, in the many years that have passed since my PhD, I am still motivated by the same excitement of new opportunity that characterized my early years. My joy in developing methods to teach language to children with autism parallels the excitement of work in helping to develop the evolving integrated partnerships between medicine and psychology to improve the health of children and adults. I very much view my current position in family medicine as being focused largely on two things: helping to educate patient-centered doctors and helping families to be active, informed partners in their health care. In both, creating a work force of pediatric and health psychologists is critical. It has been a wonderful career with opportunities to observe and apply our growing literature to the changing environments and practice of pediatric care.

Among the things that I have learned in my many years of work in medical settings is that doctors love pearls. No, not the kind you wear around your neck, but pearls of wisdom! Every year, as we graduate a new class of family physicians, our faculty provides to the graduating class what we consider to be pearls of wisdom—ideas that will allow young doctors to become great doctors committed to the care of their patients.

I think that pearls often have great value, which, if we utilize them, will greatly influence our practice, our findings, and our abilities to assist children and families. I am not above borrowing some of my colleagues’ best ideas. So, rather than providing vague and general statements about the future, I would like to close by sharing, with colleagues and students, some pearls in pediatric psychology.

Some Pearls

Environments Shape Behavior

Set up medical and home environments to reward and maintain healthy behavior

It Takes a Family

Educating and supporting parents is the best medicine

Catch ‘em While They’re Young

Health can often be improved by small changes made early

Morbidity Can Be a Family Affair

Children may suffer the same illnesses as their parents

Building Competencies Reduces Emergencies and Morbidity

Patients and families who know what to do can better take care of themselves

TeamCare, Before There’s a Problem

Pediatric psychologists at the point-of-care as part of the team with doctors and nurses

Speak the Language

Screener, warm handoff, curbside consult, huddle

Get Out of Your Office

Time-of-care, place-of-care, face-to-face encounters while child is receiving medical care

It’s not Psychotherapy

Lose the 50-minute hour. Quick encounters fit the flow of the medical environment

No Termination

If you go to the doctor for a cold, you can comeback for checkups or when you feel sick

Conflicts of interest: None declared.