-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jane M. Robertson, Alison Bowes, Grant Gibson, Louise McCabe, Emma, L. Reynish, Alasdair C. Rutherford, Monika Wilińska, Spotlight on Scotland: Assets and Opportunities for Aging Research in a Shifting Sociopolitical Landscape, The Gerontologist, Volume 56, Issue 6, 1 December 2016, Pages 979–989, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw058

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Scotland is a small nation, yet it leads the field in key areas of aging research. With the creation of a devolved government with authority over health and social services, the country has witnessed practice and policy developments that offer distinctive opportunities for innovative research. With multidisciplinary groups of internationally recognized researchers, Scotland is able to take advantage of a unique set of opportunities for aging research: a well-profiled population brings opportunities in population data and linkage to understand people’s interactions with health, social care, and other public services; while research on technology and telecare is a distinctive area where Scotland is recognized internationally for using technology to develop effective, high-quality and well-accepted services at relatively low financial cost. The paper also considers free personal care for older people and the national dementia strategy in Scotland. The potential to evaluate the impact of free personal care will provide valuable information for other global health and social care systems. Exploring the impact of the national dementia strategy is another unique area of research that can advance understanding in relation to quality of life and the development of services. The paper concludes that, while Scotland benefits from unique opportunities for progressive public policy and innovative aging research that will provide valuable lessons at the forefront of a globally aging population, the challenges associated with an aging population and increasing cultural diversity must be acknowledged and addressed to ensure that the vision of equality and social justice for all is realized.

Scotland forms the northern part of the United Kingdom. It covers nearly a third of the land mass of Great Britain, and yet its population accounts for 8% of the total U.K. population of Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, and Wales (Office of National Statistics, 2014). Politically Scotland falls under the remit of the government of the United Kingdom (London). However, a devolved Scottish Parliament created in 1997 has authority over a range of issues including: education, health and social services, housing, law and order, local government, and the environment. The UK Parliament governs key reserved areas including: benefits and social security, defense and foreign policy, employment, immigration, and trade and industry.

The links between Scotland and the other U.K. nations continue to evolve with ongoing constitutional change and reform. A mix of devolved and reserved constitutional powers provides a distinct and dynamic context in which policies affecting older people have developed over the last 2 decades. Policy approaches to an aging population have placed specific emphasis on health and social care, including: delivering free personal care, promoting telecare innovation, and setting out a national framework for supporting people with dementia and their carers. Within this context, the opportunities for aging research in Scotland are broad, with distinct areas of research that benefit from the uniqueness of the Scottish infrastructure.

In Scotland, health care is publicly funded through taxation and provided free at the point of need by the National Health Service (NHS). Although public health care dominates, private health care is available for those willing to pay. Publicly funded social care is provided on a means-tested basis, although elements of this provision are offered free, as will be described below in relation to free personal care. The private and third sectors are also significant providers of social care in Scotland. Health and social care policy is devolved to the Scottish Government and therefore separate from policy in other parts of the United Kingdom. The NHS in Scotland comprises 14 geographically based health boards and 7 national special health boards, while 32 local authorities areas or “councils” are responsible for social care provision. In 2014, Scottish health and social care systems were integrated to improve the coordination of health and social care delivery. This statutory integration of health and social care sets Scotland apart from the other U.K. nations, and Scotland is also notable for its abolition of prescription charges in 2011.

This paper will describe the funding infrastructure and ongoing areas of research, consider two areas of interest that highlight unique opportunities for research (population data and linkage, and technology and telecare), and highlight two public policy issues that are distinct to Scotland and offer particular research opportunities—free personal care for older people and a national dementia strategy. In the context of an aging population and increasing net migration, pension poverty and cultural diversity are considered as key emerging issues affecting older people living in Scotland.

Demographics of Aging in Scotland

An Aging Population

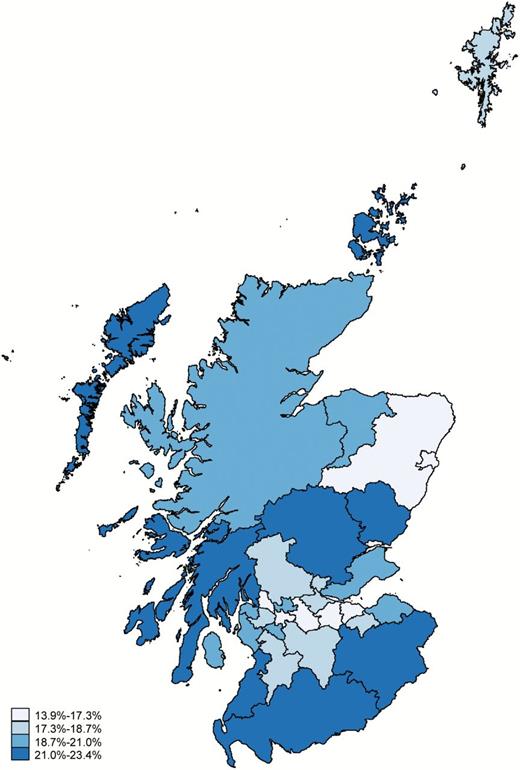

Scotland has a population of 5,347,600 (National Records of Scotland, 2015b) with more than 81% living in urban areas (Office of National Statistics, 2012). The country is characterized by an urban “central belt” between its two biggest cities—Glasgow and Edinburgh—with larger rural landscapes in the borders to the south and the highlands and islands in the north. More remote communities have disproportionally older populations compared to the larger cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen, as shown in the map on Figure 1 (National Records of Scotland, 2015a). Around 12.9% of those aged 85–89 and 23.3% of those aged 90–94 were resident in either hospitals or care homes in the 2011 census, with higher rates for women than men (National Records of Scotland, 2011).

Older population (65+) density (percentages) in Scotland by council areas, mid-2013. Source: UK Office of National Statistics. Note: An interactive map can also be found here: http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ods-web/datavis.jsp?theme=Population_v4_September_2013 (accessed February 24, 2016).

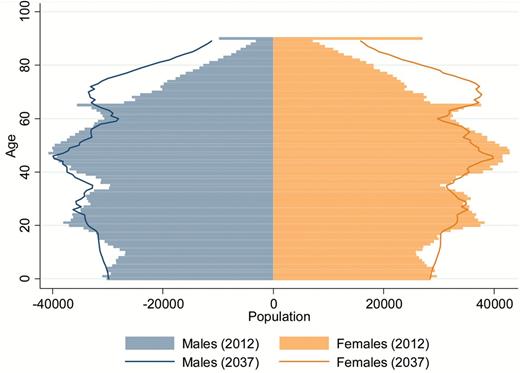

In Scotland, 18% of the population are aged 65 and older and 2% are aged 85 and older (National Records of Scotland, 2015a). Figure 2 shows that the proportion of older people is projected to rise dramatically as the number of people aged 60–74 increases by 21%, and people aged 75 and older by 86%, between 2012 and 2037, while the size of the population younger than 65 remains fairly constant (National Records of Scotland, 2013b). In common with other developed countries, Scotland’s life expectancy has increased over the past 30 years, with life expectancy at age 65 for men reaching 17.1 years and for women reaching 19.5 years (Office of National Statistics, 2013), although this is the lowest of the nations within the United Kingdom.

Estimated and projected age structure of Scotland’s population, mid-2012 and mid-2037. Source: National Records of Scotland. Note: Reproduced based on National Records of Scotland data (original data file name: population-pyramids-1981-2037_0.xlsx).

Significant inequality exists within this general trend of increased life expectancy, with the most deprived areas of Scotland having a lower life expectancy at age 65—3 years for men and 2 years for women—compared to the most affluent areas (Clark, McKeon, Sutton, & Wood, 2004). This demographic creates the so-called “Glasgow effect” with a stark contrast in health between poorer city communities and more affluent suburbs separated by only a few miles (Walsh, Bendel, Jones, & Hanlon, 2010). Increasing pensioner poverty is an issue that Scotland shares with other nations in the United Kingdom since social security is an area of policy not yet devolved from the U.K. government. In this U.K. context, welfare policy is shifting risk and responsibility from the state towards individuals, in parallel with a rise in state retirement age (68 years), to increase the time that older adults are productively engaged and financially independent (Coole, 2012). In addition to the risk that many are ill-prepared for this change, with inadequate pensions and savings (Age UK, 2014; Fenge et al., 2012; Scottish Government, 2015b), those from the most deprived areas of Scotland have a life expectancy that does not reach beyond the current state retirement age. Tackling this inequality, which is only likely to increase as responsibility for retirement savings shifts to individuals, must therefore be a priority for public policy.

Migration and Cultural Diversity

The most recent census data from 2011 indicates that the majority of the population—84%—recorded their ethnicity as White; Scottish, with the second largest group—8%—recorded as White; Other British; only 4% of the Scottish population are from minority ethnic groups, although this percentage has doubled from 2001 (National Records of Scotland, 2013a). The Asian population is the largest minority ethnic group—3% of the total population—while just over 1% of the population recorded their ethnicity as White Polish (National Records of Scotland, 2013a).

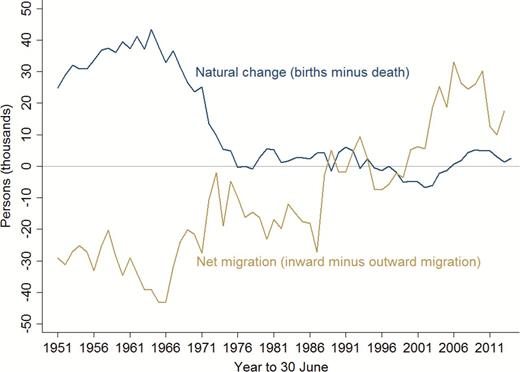

As evident in Figure 3, net migration (inward minus outward migration) has increased in the last 10 years while natural change (births minus deaths) has stabilized (National Records of Scotland, 2015b). The last decade has therefore brought significant changes to the ethnic composition of the population: between 2001 and 2011, there was a 93% increase in the non-U.K.-born population in Scotland (Krausova & Vargas-Silva, 2013), with growing diversity in communities, particularly the significant increase in Central and Eastern European migrants. This changing demographic will necessitate a more pluralistic approach to policy and will require research that can explore multicultural perspectives on aging to embrace this increasingly diverse population.

Natural change and net migration in Scotland, 1951–2014. Source: National Records of Scotland.

Religiosity and religion is also changing in Scotland, with an increase in the proportion of the population recording that they have no religion—increasing 9 points between 2001 and 2013 to represent 37% of the population (National Records of Scotland, 2013a). Christianity remains the main religion in Scotland, with 54% of the population identifying themselves as Christian, although this is a decrease of 11% points since 2001. Just over 1% of the population recorded themselves as Muslim, an increase in 0.6% points since 2001, with Buddhist, Hindus, and Sikhs accounting for 0.7% of the population, again indicating an increase since 2001, while the Jewish population has declined to only 0.1% of people living in Scotland (National Records of Scotland, 2013a). Religious diversity is therefore increasing, and while Christianity remains the dominant religion, there has been a sharp decrease in those identifying themselves as Christian, associated with an increase in those with no religion.

As ethnic and cultural diversity increases, so policies will have to engage more fully with the rights and needs of older people from varied backgrounds to promote equality and inclusion for all people aging in Scotland. Despite the emphasis placed on social justice in Scottish strategies (Scottish Government, 1999), it is recognized that older people from minority ethnic groups encounter barriers to accessing care and support (Bowes, Avan, & Macintosh, 2012). Research in Scotland indicates that cultural diversity and ethnicity are perceived as peripheral to the main concerns of health and care providers (Bowes and Dar, 2000; Bowes and Wilkinson, 2003). This inattention is consistent with U.K.-wide trends in which gerontological research has tended to neglect ethnic diversity (Victor, Burholt, & Martin, 2012) and policies such as safeguarding lack cultural competence and sensitivity (Manthorpe & Bowes, 2010) that may ultimately lead to misunderstandings and mistreatment of older people from minority ethnic groups (Bowes et al., 2012).

The Scottish Government has so far invested in several scoping projects to examine the needs of older people from minority ethnic groups. For example, the Securing Care for Ethnic Elders in Scotland (SCEES) program (www.priae.org, accessed February 24, 2016)—funded within a broader governmental Multiple and Complex Needs (MCN) initiative (Scottish Government Social Research, 2009)—engaged older people from minority ethnic groups to work in areas such as prevention, palliative care, and patient-centered hospital care. Despite the introduction of such scoping projects, a more integrated approach is required that targets society at large to counteract ethnic discrimination and cultural misunderstandings. The context of Scottish policy on equality and inclusion among older people (Scottish Government, 2011b) creates a promising framework that has yet to be utilized. Consequently, research and policy must engage with social and cultural distinctions more fully to meet the challenges and embrace the opportunities that result from increasing diversity in the Scottish population.

Multidisciplinary Research Expertise in Scotland

Tables 1 and 2 set out the research centers, groups, and networks that currently function in Scotland in addition to specialist degree level programs available in aging and dementia. A vibrant and multidisciplinary community of researchers is at the forefront of various fields of aging research.

Aging and dementia research centers, groups, and networks in Scotland

| Institution . | Research centre . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Aberdeen | Aberdeen Gerontological and Epidemiological INterdisciplinary Group | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/iahs/research/epidemiology/research-107.php |

| Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disease Research | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/ims/ (accessed February 24, 2016) research/neuroscience/ageing-and-neurodegenerative-disease.php (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Dundee | Alzheimer’s Research UK Scotland Network Centre | http://www.dundee.ac.uk/alzheimer/centre.htm (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Edinburgh | Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre | http://www.alzscotdrc.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/clinical-brain-sciences (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| A new centre at the University of Edinburgh launched in November 2015: Centre for Dementia Prevention http://centrefordementiaprevention.com/Edinburgh Delirium Research Group | http://www.edinburghdelirium.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology | http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| School of Health in Social Science: Dementia and Ageing | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/health/research/themes/dementia-ageing (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Glasgow | Glasgow Ageing Research Network | http://www.gla.ac.uk/researchinstitutes/bahcm/research/sigs/garner/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia and Social Gerontology Research Group | http://www.stir.ac.uk/social-science/research/research-areas/dementia-and-social-gerontology/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Services Development Centre | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland | http://www.hagis.scot/ | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Alzheimer Scotland Centre for Policy and Practice | http://www.uws.ac.uk/schools/school-of-health-nursing-and-midwifery/research/alzheimer-scotland-centre-for-policy-and-practice/ |

| Gerontology Interest Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/gerontology-interest-group/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Older Persons’ Health and Wellbeing Subject Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/institute-of-older-persons--health-and-wellbeing/# (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scotland-wide networks on aging and dementia | British Society of Geriatrics - Scotland | http://www.bgs-scotland.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| British Society of Gerontology Scotland Working Group | http://www.britishgerontology.org/membership/bsg-scotland.html (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Delirium Association | https://sites.google.com/site/scottishdeliriumassociation/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Research Consortium | http:// scottishdementiaresearchconsortium.org/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Stroke Research Network | http://www.ssrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| U.K.-wide clinical network on aging with Scottish constituent | UK NIHR Clinical Research Network for Ageing | https://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/ageing/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Institution . | Research centre . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Aberdeen | Aberdeen Gerontological and Epidemiological INterdisciplinary Group | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/iahs/research/epidemiology/research-107.php |

| Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disease Research | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/ims/ (accessed February 24, 2016) research/neuroscience/ageing-and-neurodegenerative-disease.php (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Dundee | Alzheimer’s Research UK Scotland Network Centre | http://www.dundee.ac.uk/alzheimer/centre.htm (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Edinburgh | Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre | http://www.alzscotdrc.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/clinical-brain-sciences (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| A new centre at the University of Edinburgh launched in November 2015: Centre for Dementia Prevention http://centrefordementiaprevention.com/Edinburgh Delirium Research Group | http://www.edinburghdelirium.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology | http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| School of Health in Social Science: Dementia and Ageing | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/health/research/themes/dementia-ageing (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Glasgow | Glasgow Ageing Research Network | http://www.gla.ac.uk/researchinstitutes/bahcm/research/sigs/garner/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia and Social Gerontology Research Group | http://www.stir.ac.uk/social-science/research/research-areas/dementia-and-social-gerontology/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Services Development Centre | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland | http://www.hagis.scot/ | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Alzheimer Scotland Centre for Policy and Practice | http://www.uws.ac.uk/schools/school-of-health-nursing-and-midwifery/research/alzheimer-scotland-centre-for-policy-and-practice/ |

| Gerontology Interest Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/gerontology-interest-group/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Older Persons’ Health and Wellbeing Subject Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/institute-of-older-persons--health-and-wellbeing/# (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scotland-wide networks on aging and dementia | British Society of Geriatrics - Scotland | http://www.bgs-scotland.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| British Society of Gerontology Scotland Working Group | http://www.britishgerontology.org/membership/bsg-scotland.html (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Delirium Association | https://sites.google.com/site/scottishdeliriumassociation/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Research Consortium | http:// scottishdementiaresearchconsortium.org/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Stroke Research Network | http://www.ssrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| U.K.-wide clinical network on aging with Scottish constituent | UK NIHR Clinical Research Network for Ageing | https://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/ageing/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Aging and dementia research centers, groups, and networks in Scotland

| Institution . | Research centre . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Aberdeen | Aberdeen Gerontological and Epidemiological INterdisciplinary Group | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/iahs/research/epidemiology/research-107.php |

| Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disease Research | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/ims/ (accessed February 24, 2016) research/neuroscience/ageing-and-neurodegenerative-disease.php (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Dundee | Alzheimer’s Research UK Scotland Network Centre | http://www.dundee.ac.uk/alzheimer/centre.htm (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Edinburgh | Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre | http://www.alzscotdrc.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/clinical-brain-sciences (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| A new centre at the University of Edinburgh launched in November 2015: Centre for Dementia Prevention http://centrefordementiaprevention.com/Edinburgh Delirium Research Group | http://www.edinburghdelirium.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology | http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| School of Health in Social Science: Dementia and Ageing | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/health/research/themes/dementia-ageing (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Glasgow | Glasgow Ageing Research Network | http://www.gla.ac.uk/researchinstitutes/bahcm/research/sigs/garner/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia and Social Gerontology Research Group | http://www.stir.ac.uk/social-science/research/research-areas/dementia-and-social-gerontology/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Services Development Centre | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland | http://www.hagis.scot/ | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Alzheimer Scotland Centre for Policy and Practice | http://www.uws.ac.uk/schools/school-of-health-nursing-and-midwifery/research/alzheimer-scotland-centre-for-policy-and-practice/ |

| Gerontology Interest Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/gerontology-interest-group/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Older Persons’ Health and Wellbeing Subject Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/institute-of-older-persons--health-and-wellbeing/# (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scotland-wide networks on aging and dementia | British Society of Geriatrics - Scotland | http://www.bgs-scotland.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| British Society of Gerontology Scotland Working Group | http://www.britishgerontology.org/membership/bsg-scotland.html (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Delirium Association | https://sites.google.com/site/scottishdeliriumassociation/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Research Consortium | http:// scottishdementiaresearchconsortium.org/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Stroke Research Network | http://www.ssrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| U.K.-wide clinical network on aging with Scottish constituent | UK NIHR Clinical Research Network for Ageing | https://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/ageing/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Institution . | Research centre . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Aberdeen | Aberdeen Gerontological and Epidemiological INterdisciplinary Group | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/iahs/research/epidemiology/research-107.php |

| Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disease Research | http://www.abdn.ac.uk/ims/ (accessed February 24, 2016) research/neuroscience/ageing-and-neurodegenerative-disease.php (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Dundee | Alzheimer’s Research UK Scotland Network Centre | http://www.dundee.ac.uk/alzheimer/centre.htm (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Edinburgh | Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre | http://www.alzscotdrc.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/clinical-brain-sciences (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| A new centre at the University of Edinburgh launched in November 2015: Centre for Dementia Prevention http://centrefordementiaprevention.com/Edinburgh Delirium Research Group | http://www.edinburghdelirium.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology | http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| School of Health in Social Science: Dementia and Ageing | http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/health/research/themes/dementia-ageing (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of Glasgow | Glasgow Ageing Research Network | http://www.gla.ac.uk/researchinstitutes/bahcm/research/sigs/garner/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia and Social Gerontology Research Group | http://www.stir.ac.uk/social-science/research/research-areas/dementia-and-social-gerontology/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Services Development Centre | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland | http://www.hagis.scot/ | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Alzheimer Scotland Centre for Policy and Practice | http://www.uws.ac.uk/schools/school-of-health-nursing-and-midwifery/research/alzheimer-scotland-centre-for-policy-and-practice/ |

| Gerontology Interest Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/gerontology-interest-group/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Older Persons’ Health and Wellbeing Subject Group | http://www.uws.ac.uk/research/research-institutes/health/institute-of-older-persons--health-and-wellbeing/# (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scotland-wide networks on aging and dementia | British Society of Geriatrics - Scotland | http://www.bgs-scotland.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| British Society of Gerontology Scotland Working Group | http://www.britishgerontology.org/membership/bsg-scotland.html (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Delirium Association | https://sites.google.com/site/scottishdeliriumassociation/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Dementia Research Consortium | http:// scottishdementiaresearchconsortium.org/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Scottish Stroke Research Network | http://www.ssrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| U.K.-wide clinical network on aging with Scottish constituent | UK NIHR Clinical Research Network for Ageing | https://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/ageing/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Specialist degree programs in gerontology and dementia in Scotland

| Institution . | Degree . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Edinburgh | Dementia: International Experience, Policy and Practice (MSc) | http://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/view&id=760 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia Studies (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/applied-social-science/dementia-studies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Studies (Undergraduate) | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/education/advanced-study/undergraduate (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Health and Wellbeing of the Older Person (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/health-sciences/healthandwellbeingoftheolderperson/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Later Life Studies (MSc) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/msclaterlifestudies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Working With Older People (Graduate Certificate) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/postgraduate/working_with_older_people/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Institution . | Degree . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Edinburgh | Dementia: International Experience, Policy and Practice (MSc) | http://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/view&id=760 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia Studies (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/applied-social-science/dementia-studies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Studies (Undergraduate) | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/education/advanced-study/undergraduate (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Health and Wellbeing of the Older Person (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/health-sciences/healthandwellbeingoftheolderperson/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Later Life Studies (MSc) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/msclaterlifestudies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Working With Older People (Graduate Certificate) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/postgraduate/working_with_older_people/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Specialist degree programs in gerontology and dementia in Scotland

| Institution . | Degree . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Edinburgh | Dementia: International Experience, Policy and Practice (MSc) | http://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/view&id=760 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia Studies (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/applied-social-science/dementia-studies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Studies (Undergraduate) | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/education/advanced-study/undergraduate (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Health and Wellbeing of the Older Person (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/health-sciences/healthandwellbeingoftheolderperson/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Later Life Studies (MSc) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/msclaterlifestudies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Working With Older People (Graduate Certificate) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/postgraduate/working_with_older_people/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Institution . | Degree . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| University of Edinburgh | Dementia: International Experience, Policy and Practice (MSc) | http://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/view&id=760 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| University of Stirling | Dementia Studies (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/applied-social-science/dementia-studies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Dementia Studies (Undergraduate) | http://dementia.stir.ac.uk/education/advanced-study/undergraduate (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| Health and Wellbeing of the Older Person (MSc, PGDip, PGCert) | http://www.stir.ac.uk/postgraduate/programme-information/prospectus/health-sciences/healthandwellbeingoftheolderperson/ (accessed February 24, 2016) | |

| University of the West of Scotland | Later Life Studies (MSc) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/msclaterlifestudies/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Working With Older People (Graduate Certificate) | http://www.uws.ac.uk/postgraduate/working_with_older_people/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Funding Infrastructure

While the paper considers unique opportunities for research in the context of health and social care policies introduced by a devolved Scottish Government, it is notable that the majority of the funding for this research is not devolved. There are two main strands of research funding in the United Kingdom: (a) block funding of Higher Education (HE) institutions by the HE funding councils—in this context, Scottish universities receive funding for research and teaching from the Scottish Funding Council (www.sfc.ac.uk/, accessed February 24, 2016); (b) competitive funding for research grants, fellowships, and studentships from the UK Research Councils (RCUK) (www.rcuk.ac.uk/, accessed February 24, 2016). The RCUK continues to be a significant funder of biomedical, economic, and social research in Scotland, and the country has fared well compared to other U.K. nations, receiving 11% share of the RCUK spend relative to 8% proportion of the U.K. population (RCUK, 2014). Other sources of funding include: the European Union, Scottish Government, UK Department of Health, trusts such as Carnegie (www.carnegie-trust.org/, accessed February 24, 2016), and third sector charitable organizations such as the Royal Society of Edinburgh (www.royalsoced.org.uk/, accessed February 24, 2016) and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (www.jrf.org.uk, accessed February 24, 2016). Similarly to the situation with RCUK funding, Scotland punches above its weight in relation to U.K. charity funding, with Scotland consistently representing 12–13% of United Kingdom spend on medical and health research (Association of Medical Research Charities, 2013). The Scottish research infrastructure is therefore underpinned by significant investment from U.K. public and third sector funding.

Research Centers and Networks

The field of gerontology in Scotland exists within health and social science faculties; and while many individual researchers identify themselves as gerontologists or aging studies academics, there are only a few specialist research groups and centers. At the University of Stirling, the School of Applied Social Science brings together sociologists, psychologists, social workers, nurses, economists, anthropologists, and geriatricians to consider the social aspects of aging and dementia and to evaluate current approaches to care and support. At the University of the West of Scotland, a mix of nurses and other allied health professionals in the Institute of Healthcare Policy and Practice focus on the well-being of older people. In Edinburgh, aging research sits within the School of Health in Social Science, reflecting an interdisciplinary approach towards an understanding of experiences, policy, practice, and society. In addition to a broad interest in the well-being of older people, these research centers are distinctive for their emphasis on understanding dementia in aging research.

The importance placed on promoting dementia research is reflected in the existence of the Scottish Dementia Research Consortium which assists research across Scotland. This organization is supported at a strategic level and forms part of the current Scottish dementia strategy, which is discussed further below. Within the social sciences, the University of Stirling and the University of Edinburgh are key sites with expertise in researching dementia and delivering international e-learning programs in Dementia Studies. Specific centers also exist to advance research, practice, and policy in the field of dementia care. The Dementia Services Development Centre at the University of Stirling is the longest-standing and recognized as a model for converting world-leading research into everyday good practice in caring for people with dementia. The Alzheimer Scotland Centre for Policy and Practice at the University of the West of Scotland is a more recent center focusing on innovation in applied research. Additionally, individual researchers work across other centers of higher education in Scotland, reflecting widespread interest in the condition.

Biomedical research in Scotland falls into two camps: disease-specific research and aging research. Aging research is grouped under the UK NIHR Clinical Research Network for Ageing with a predominant grouping of academics in geriatric medicine based in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Stirling. In the clinical field, overlaps with dementia research are numerous. The Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network is coordinated in Perth and Edinburgh and focuses on the delivery of clinical trials in Scotland. Dementia research centers are found in Stirling (focusing on multidisciplinary population and health services research with a specific interest in outcomes) and Edinburgh (focusing on clinical research in addition to holding a dementia brain tissue bank to understand the neurological processes that lead to dementia). The University of Aberdeen focuses on degenerative diseases of aging and also holds a brain tissue bank, while medical research is the emphasis of the Alzheimer’s Research UK Scotland Network Centre at the University of Dundee. A research group concerned with delirium is based in Edinburgh, while active care home research is led from Glasgow, and stroke research flourishes in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Dundee.

Epidemiological research is found in most centers but the Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology in Edinburgh produces ground-breaking research on normal cognitive aging. Population data sets including routine health and social care data are held in the Health Informatics Centre in Dundee. As will be discussed in the next section examining assets and opportunities for aging research, these data sets and record linkages provide unique rich resources in Scotland.

Assets and Opportunities for Aging Research

With multidisciplinary groups of researchers, Scotland is able to take advantage of various assets and opportunities for aging research. New opportunities in population data and linkage are emerging, while research on technology and telecare is a distinctive area where Scotland is leading the field.

Population Data and Linkage

Scotland benefits from both being part of U.K.-wide social surveys and Scotland-specific surveys. The main social surveys that can be used to study aging in Scotland are: the Scottish Household Survey and the Scottish Health Survey, both commissioned by the Scottish Government. These surveys collect nationally representative cross-sectional data for the Scottish population, with annual sample sizes of 10,000 and 4,000 adults, respectively. Longitudinal survey data are available from the UK Household Longitudinal Study—“Understanding Society”—that includes a significant Scottish sample. While Scotland does not benefit from having an equivalent of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) to track a large sample of older people over time, work is underway to pilot a similar study entitled Health and Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS). See Table 3 for links to these data sets.

Secondary data sets available to researchers in Scotland

| Data set . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS) | The first longitudinal study of Scotland’s older people, following individuals and households through time. Currently in its pilot phase. | www.hagis.scot (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Health Survey | The survey provides a detailed picture of the health of the Scottish population in private households to assist with health monitoring. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/scottish-health-survey (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Household Survey | The survey is designed to provide accurate information about the characteristics, attitudes, and behavior of Scottish households and individuals. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/16002 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| UK Household Longitudinal Study (Understanding Society) | The largest household survey of its kind, it captures information about people’s social and economic circumstances, attitudes, behaviors, and health. | https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Data set . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS) | The first longitudinal study of Scotland’s older people, following individuals and households through time. Currently in its pilot phase. | www.hagis.scot (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Health Survey | The survey provides a detailed picture of the health of the Scottish population in private households to assist with health monitoring. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/scottish-health-survey (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Household Survey | The survey is designed to provide accurate information about the characteristics, attitudes, and behavior of Scottish households and individuals. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/16002 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| UK Household Longitudinal Study (Understanding Society) | The largest household survey of its kind, it captures information about people’s social and economic circumstances, attitudes, behaviors, and health. | https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Secondary data sets available to researchers in Scotland

| Data set . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS) | The first longitudinal study of Scotland’s older people, following individuals and households through time. Currently in its pilot phase. | www.hagis.scot (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Health Survey | The survey provides a detailed picture of the health of the Scottish population in private households to assist with health monitoring. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/scottish-health-survey (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Household Survey | The survey is designed to provide accurate information about the characteristics, attitudes, and behavior of Scottish households and individuals. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/16002 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| UK Household Longitudinal Study (Understanding Society) | The largest household survey of its kind, it captures information about people’s social and economic circumstances, attitudes, behaviors, and health. | https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Data set . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS) | The first longitudinal study of Scotland’s older people, following individuals and households through time. Currently in its pilot phase. | www.hagis.scot (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Health Survey | The survey provides a detailed picture of the health of the Scottish population in private households to assist with health monitoring. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/scottish-health-survey (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Household Survey | The survey is designed to provide accurate information about the characteristics, attitudes, and behavior of Scottish households and individuals. | http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/16002 (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| UK Household Longitudinal Study (Understanding Society) | The largest household survey of its kind, it captures information about people’s social and economic circumstances, attitudes, behaviors, and health. | https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Scotland has long pioneered the use of linked health and social service data for research. The NHS in Scotland uses a unique Community Health Index (CHI) number to identify patients. The CHI number facilitates linkage to other datasets (e.g., the Scottish Morbidity Records 01 (SMR01), General Register Office (GRO) for Scotland mortality data, the master Community Health Index (CHI) dataset, and the patient-level community dispensed prescribing dataset). Researchers have already benefitted from the Scottish Government’s integrated resource framework (IRF) which helps them identify relationships between health, social care activity, and resource use. Development of the health and bioinformatics research infrastructure in Scotland is ongoing. The establishment of a Stratified Medicine Applied Research Programme is part of the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office’s (CSO) future research strategy. Important resources for data linkage and data use in Scotland are provided in Table 4.

Important resources for data linkage and data use in Scotland

| Resource . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative Data Research Centre Scotland (ADRC) | Brings together major Scottish research centers, led by the University of Edinburgh. It gives accredited researchers access to linked, de-identified administrative data in a secure environment. | http://adrn.ac.uk/centres/scotland (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) | Provides a single point of contact to assist researchers in study design, approvals, and access to Scottish health data (originating from NHS Scotland) in a secure environment. | http://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/eDRIS/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| The Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research - Scotland node (Farr Institute at Scotland) | A collaboration that harnesses health data for patient and public benefit by setting the international standard for the safe and secure use of electronic patient records and other population-based datasets for research purposes. | http://www.farrinstitute.org/centre/Scotland/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Centre Services (HIC Services) | University of Dundee research support unit within the Tayside Medical Science Centre and the Farr Institute, in collaboration with NHS Tayside and NHS Fife. Supports the collection and management of high-quality data. | http://medicine.dundee.ac.uk/hic (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Research Advisory Group (HIRAG) | Coordinates and monitors developments in e-health informatics research, considering required investment and advising the Scottish Government on its strategies for e-health and electronic records search. | http://www.cso.scot.nhs.uk/about/initiatives/hirag/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) | Set up to improve the quantity and quality of dementia research, the network holds a register with names, contact details, baseline assessments, and medical information of willing participants interested in research about dementia. | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Imaging Network: A Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) | A consortium of six universities—Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, and Stirling—developing expertise in: MRI and advanced techniques, PET and SPECT, EEG and fMRI, imaging trials, and partnership working. | http://www.sinapse.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Resource . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative Data Research Centre Scotland (ADRC) | Brings together major Scottish research centers, led by the University of Edinburgh. It gives accredited researchers access to linked, de-identified administrative data in a secure environment. | http://adrn.ac.uk/centres/scotland (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) | Provides a single point of contact to assist researchers in study design, approvals, and access to Scottish health data (originating from NHS Scotland) in a secure environment. | http://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/eDRIS/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| The Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research - Scotland node (Farr Institute at Scotland) | A collaboration that harnesses health data for patient and public benefit by setting the international standard for the safe and secure use of electronic patient records and other population-based datasets for research purposes. | http://www.farrinstitute.org/centre/Scotland/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Centre Services (HIC Services) | University of Dundee research support unit within the Tayside Medical Science Centre and the Farr Institute, in collaboration with NHS Tayside and NHS Fife. Supports the collection and management of high-quality data. | http://medicine.dundee.ac.uk/hic (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Research Advisory Group (HIRAG) | Coordinates and monitors developments in e-health informatics research, considering required investment and advising the Scottish Government on its strategies for e-health and electronic records search. | http://www.cso.scot.nhs.uk/about/initiatives/hirag/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) | Set up to improve the quantity and quality of dementia research, the network holds a register with names, contact details, baseline assessments, and medical information of willing participants interested in research about dementia. | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Imaging Network: A Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) | A consortium of six universities—Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, and Stirling—developing expertise in: MRI and advanced techniques, PET and SPECT, EEG and fMRI, imaging trials, and partnership working. | http://www.sinapse.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Important resources for data linkage and data use in Scotland

| Resource . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative Data Research Centre Scotland (ADRC) | Brings together major Scottish research centers, led by the University of Edinburgh. It gives accredited researchers access to linked, de-identified administrative data in a secure environment. | http://adrn.ac.uk/centres/scotland (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) | Provides a single point of contact to assist researchers in study design, approvals, and access to Scottish health data (originating from NHS Scotland) in a secure environment. | http://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/eDRIS/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| The Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research - Scotland node (Farr Institute at Scotland) | A collaboration that harnesses health data for patient and public benefit by setting the international standard for the safe and secure use of electronic patient records and other population-based datasets for research purposes. | http://www.farrinstitute.org/centre/Scotland/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Centre Services (HIC Services) | University of Dundee research support unit within the Tayside Medical Science Centre and the Farr Institute, in collaboration with NHS Tayside and NHS Fife. Supports the collection and management of high-quality data. | http://medicine.dundee.ac.uk/hic (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Research Advisory Group (HIRAG) | Coordinates and monitors developments in e-health informatics research, considering required investment and advising the Scottish Government on its strategies for e-health and electronic records search. | http://www.cso.scot.nhs.uk/about/initiatives/hirag/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) | Set up to improve the quantity and quality of dementia research, the network holds a register with names, contact details, baseline assessments, and medical information of willing participants interested in research about dementia. | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Imaging Network: A Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) | A consortium of six universities—Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, and Stirling—developing expertise in: MRI and advanced techniques, PET and SPECT, EEG and fMRI, imaging trials, and partnership working. | http://www.sinapse.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Resource . | Details . | Website . |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative Data Research Centre Scotland (ADRC) | Brings together major Scottish research centers, led by the University of Edinburgh. It gives accredited researchers access to linked, de-identified administrative data in a secure environment. | http://adrn.ac.uk/centres/scotland (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) | Provides a single point of contact to assist researchers in study design, approvals, and access to Scottish health data (originating from NHS Scotland) in a secure environment. | http://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/eDRIS/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| The Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research - Scotland node (Farr Institute at Scotland) | A collaboration that harnesses health data for patient and public benefit by setting the international standard for the safe and secure use of electronic patient records and other population-based datasets for research purposes. | http://www.farrinstitute.org/centre/Scotland/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Centre Services (HIC Services) | University of Dundee research support unit within the Tayside Medical Science Centre and the Farr Institute, in collaboration with NHS Tayside and NHS Fife. Supports the collection and management of high-quality data. | http://medicine.dundee.ac.uk/hic (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Health Informatics Research Advisory Group (HIRAG) | Coordinates and monitors developments in e-health informatics research, considering required investment and advising the Scottish Government on its strategies for e-health and electronic records search. | http://www.cso.scot.nhs.uk/about/initiatives/hirag/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) | Set up to improve the quantity and quality of dementia research, the network holds a register with names, contact details, baseline assessments, and medical information of willing participants interested in research about dementia. | http://www.sdcrn.org.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

| Scottish Imaging Network: A Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) | A consortium of six universities—Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, and Stirling—developing expertise in: MRI and advanced techniques, PET and SPECT, EEG and fMRI, imaging trials, and partnership working. | http://www.sinapse.ac.uk/ (accessed February 24, 2016) |

Data linkage is a highly efficient way of conducting research and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions in delivering patient and population benefits: it allows the assessment of the impact of interventions across the population and at a lower cost than undertaking primary research (Taylor & Lynch, 2011). Increasingly, opportunities are being created to link together administrative and social survey data. For instance, the connection between behavioral, biological, and social risk factors and subsequent hospital admission has been analyzed by linking data from the Scottish Health Survey with the Scottish hospital admission database (Hanlon et al., 2007). Such data linkage developments help us to understand people’s interactions with health, social care, and other public services on a large scale that is not possible in most other countries (Scottish Government, 2011a).

Technology and Telecare

Scotland has been acknowledged as a leader in Europe in the development of technology-enabled health and social care services. Technology has been identified through its potential to assist in providing care for the significant portions of the Scottish population who live in rural and often isolated areas outside the central belt (Scottish Government, 2012a). Reflecting a rights-based approach to care in Scotland, technology-enabled services start not with viewing those receiving care as “patients” or “service users” with health or social care needs, but as whole persons with rights regarding decision making, social inclusion, and citizenship such as independence, participation, and identity. A number of services have developed which seek to extend beyond the simple provision of care, to instead provide holistic services integrated within the whole health and social care system and tailored to individual need. An example of a technology-enabled service in Scotland is described here.

Established in 2001, West Lothian County Council pioneered telecare provision in Scotland and the wider United Kingdom. Focusing on the goal of mainstreaming telecare, a decision early in the project was made to make telecare services available to every household including a person over the age of 60 (Bowes & McColgan, 2013). Such a decision ensured that everyone could be helped as they aged and also removed some of the stigma frequently attached to telecare. Rather than being “bolted on” to existing services, telecare was integrated throughout local health and social care provision, with local services being redesigned to place telecare at the center. This provision resulted in positive outcomes, including a reduction in delayed discharges from hospital and greater control over social care costs (Bowes & McColgan, 2013). As a consequence, the West Lothian telecare service has been highlighted within Scotland, across the United Kingdom and internationally as an exemplar of using technology to develop effective, high-quality, and well-accepted services at a relatively low financial cost.

Policy Context for Older People and People With Dementia

Since devolution, Scottish strategies on aging—“All Our Futures: Planning for a Scotland with an Ageing Population” (Scottish Government, 2007); “Reshaping Care for Older People” (Scottish Government, 2011b)—have provided a framework in which social justice is emphasized to challenge age discrimination and improve health, care, and quality of life among older people. While the policy of free personal care aims to promote fair and equal treatment of all older people, Scotland has also been notable for placing dementia care at the forefront of health and social care policy.

Free Personal Care for Older People

Free personal care has been described frequently as a “flagship” policy of the Scottish Government from the early days of devolution. Alone among the U.K. jurisdictions, the Scottish Government opted for legislation—the Community Care and Health (Scotland Act) 2002—providing that everyone aged 65 and older in Scotland assessed as being in need of personal care should receive it without payment (UK Government, 2002). Thus, this aspect of support for older people became an area in which provision in Scotland varied significantly from other areas of the United Kingdom, demonstrating that devolution could make a significant difference to the policy landscape in Scotland.

Personal care under the legislation includes support relating to hygiene, food and diet, mobility, counseling and support, simple medical treatments, and personal assistance. In 2013–2014, 47,810 people living at home and 10,180 living in care facilities received free personal care, at a total cost to the public purse of £494m—of a total Scottish budget of £28bn (Scottish Government, 2015a). In the early years of the policy, costs rose rapidly, partly related to population aging, but more significantly due to the emergence of unmet need, that is, people in need of support who were unable to pay for it. The impact of unmet need was short-lived, but costs have continued to rise, especially for personal care delivered in people’s own homes: from £158m in 2004–2005 to £364m in 2013–2014 (Scottish Government, 2015a).

The popularity of the policy has been significant (Scottish Government, 2008), and despite several pieces of research and reviews demonstrating the large costs of the policy (Audit Scotland, 2008; Bell, Bowes, & Dawson, 2007; Scottish Government, 2008), successive Scottish Governments have remained committed to providing free personal care. The potential to evaluate the health economics of this type of care provision—and the consequent effect on direct health care and informal care—will provide valuable information for other global health and social care systems.

The Scottish National Dementia Strategy

In addition to providing free personal care, Scotland has been at the forefront of national strategy development to improve care for people with dementia. In 2016, there are approximately 90,000 people with dementia in Scotland, with around 96% older than 65 years in age (Alzheimer Scotland, 2016). The number of people living with dementia in the United Kingdom is expected to double over the next 30 years (Lewis, Karlsberg Shaffer, Sussex, O’Neill, & Cockcroft, 2014). Dementia is therefore a key issue facing Scotland and recognized as an urgent priority in the context of population aging.

Concurrent with an increase in the numbers of people living with dementia around the world as the international population ages, there has been a broad push to formalize policy relating to people with dementia and their families in the form of national dementia plans (Lin & Lewis, 2015). Scotland’s first strategy was published in 2010 (Scottish Government, 2010) with two main areas of attention: to improve hospital care and to increase diagnosis rates. A clear increase in diagnosis rates was evident at the end of the second year of the strategy, with rates well above those for England and Wales (Scottish Government, 2012b).

The first Charter of Rights (Alzheimer Scotland, 2011) is a significant outcome from work on the strategy. The rights of people with dementia and their carers have been accentuated, reflecting a focus on treating people with dementia as equal citizens, as well as improving care and support offered to them. Parallel to this work was the emergence of the Scottish Dementia Working Group (SDWG), a group of people with dementia who work to improve the lives of people with dementia. Concomitant with the promotion of civic rights, the SDWG has developed guidelines for involving people with dementia in research and maintaining a dementia friendly research community (SDWG, 2014). This approach sits well within the gerontological community in Scotland, with significant research interest in the lived experiences of people with dementia, dementia friendly communities, as well as an emphasis on coproduction and inclusion within research practice.

A second strategy for 2013–2016 has followed (Scottish Government, 2013), building on the apparent successes of the first and aiming to improve the support provided to people with dementia following a diagnosis. Consequently, since 2013, every person diagnosed with dementia in Scotland is now entitled to a minimum of 1 year’s worth of postdiagnostic support from a Link Worker. Exploring the impact of this provision is a key area for future research: examining the personal perspectives of people with dementia and their carers in relation to the impact on quality of life, in addition to exploiting data linkage opportunities to understand how this framework of support affects health and interacts with the use and delivery of other health and social care services.

Conclusion

This spotlight on Scotland has reflected on distinctive areas of research and policy where Scotland leads the field, providing unique opportunities for studying aging and its related consequences. This innovative work highlights the vibrant context of aging research in this small yet dynamic nation.

Scotland benefits from a broad spectrum of established and internationally respected research centers and the paper has highlighted the multidisciplinary nature of this community, which positions it well for developing research from a holistic and biopsychosocial perspective. This active research community delivers research across a wide range of disciplines and fields, continuing to develop distinct opportunities that exist in Scotland, such as the potential for population data and linkage. There is particular emphasis on health and social care within Scottish policy and research, and the paper has considered the flagship policy of free personal care alongside the progressive national dementia strategy that is now in its third phase of development. Both policies have social justice at their heart, with a focus on social inclusion that both reflects and influences approaches to research with older people, including people with dementia. A rights-based approach to supporting older people is also evident in pioneering work on technology and telecare in Scotland, with research advancing our understanding of the acceptability and feasibility of such novel approaches to delivering health and social care. Alongside the development of policy and service delivery over the last decade, developments in data linkage have provided opportunities for evaluating the effectiveness of health and social care policies and exploring the interrelationships between demographics, services, and outcomes. The use of innovative methodologies to evaluate progressive policy frameworks has relevance for the international community: research that can evaluate the costs and benefits of new developments, harnessing the resources of longitudinal and linked data sets, can provide valuable lessons for other nations in the context of a globally aging population. In conclusion, while Scotland benefits from unique opportunities for progressive public policy and innovative aging research, the challenges associated with an aging population—such as the risk of pensioner poverty—must be acknowledged and tackled, and the opportunities of increasing cultural diversity embraced, to ensure that Scotland realizes its vision of social justice and inclusion.

References

Alzheimer Scotland. (2011). Dementia rights: Charter of rights for people with dementia and their carers in Scotland. Alzheimer Scotland. Retrieved June 8, 2015, from http://www.demen-tiarights.org/charter-of-rights/ (accessed February 24, 2016).

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD