-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shevaun D. Neupert, Gilda E. Ennis, Jennifer L. Ramsey, Agnes A. Gall, Solving Tomorrow’s Problems Today? Daily Anticipatory Coping and Reactivity to Daily Stressors, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 71, Issue 4, July 2016, Pages 650–660, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv003

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The present study examined the day-to-day fluctuation of state-like anticipatory coping (coping employed prior to stressors) and how these coping processes relate to important outcomes for older adults (i.e., physical health, affect, memory failures).

Forty-three older adults aged 60–96 ( M = 74.65, SD = 8.19) participated in an 8-day daily diary study of anticipatory coping, stressors, health, affect, and memory failures. Participants reported anticipatory coping behaviors on one day with respect to 6 distinct stressor domains that could occur the following day.

Multilevel models indicated that anticipatory coping changes from day to day and within stressor domains. Lagged associations suggested that yesterday’s anticipatory coping for potential upcoming arguments is related to today’s physical health and affect. Increased stagnant deliberation is associated with reduced cognitive reactivity (i.e., fewer memory failures) to arguments the next day.

Taken together, these findings suggest that anticipatory coping is dynamic and associated with important daily outcomes.

Daily stressors are routine tangible events of day-to-day living (e.g., partner disputes). While daily stressors may seem minor compared to major life events, they can have immediate negative impacts on physical and psychological well-being ( Almeida, 2005 ; Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002 ). Daily stressors can accumulate over days to create persistent irritations and overloads that may result in more negative affect, physical health symptoms ( Almeida et al., 2002 ), and memory failures ( Neupert, Almeida, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2006a ). The glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis ( Sapolsky, Krey, & McEwen, 1986 ) suggests that stress accelerates the aging of the immune system, thus older adults who experience stressors may be at increased risk for acute health problems (e.g., Graham, Christian, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2006 ). Individual differences in exposure and reactivity to stressors likely contribute to the variance in older adults’ health problems. Although it is generally accepted that stress is associated with poorer health and cognitive functioning, previous work has focused on what happens after the stressor occurs.

Efforts to prevent exposure to or reduce the effects of stressors can have tremendous benefits for longevity and successful aging. Previous research has focused on the implications of stressors that have already occurred (e.g., Almeida, 2005 ; Almeida et al., 2002 ; Mroczek et al., 2013 ; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007 ; Whitehead & Bergeman, 2012 ). The present study focuses on coping behaviors, specifically anticipatory coping processes, that are used prior to the occurrence of daily stressors, and seeks to identify how these state-like anticipatory coping processes relate to three outcomes commonly examined in daily stressor research with older adults: daily physical health symptoms, daily affect, and daily memory failures.

Most information regarding coping development across the lifespan is based on cross-sectional data. These studies focus primarily on age differences in approach coping (i.e., active attempts to change stressful circumstances) and avoidance coping (i.e., efforts to avoid or manage emotions associated with stressful circumstances; Brennan, Holland, Schutte, & Moos, 2012 ). Results of these studies are quite mixed. Age-related increases and decreases in approach coping and age-related increases and decreases in avoidance coping have all been reported ( Aldwin, 1991a ; Aldwin, Sutton, Chiara, & Spiro, 1996 ; Diehl, Coyle, & Labouvie-Vief, 1996 ; Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987 ). Little or no change with age in coping responses has also been found (e.g., Diehl et al., 2014 ; McCrae, 1989 ; Whitty, 2003 ). Brennan and colleagues (2012) argued that coping is contextually dependent and influenced mainly by immediate appraisals and the characteristics of stressors at a particular point in time. To capture the contextually dependent nature of coping as it occurs within people over time, microlongitudinal studies (e.g., daily diary methods) are more appropriate than cross sectional approaches ( Lazarus, 1999 ).

Anticipatory coping involves efforts to prepare for the stressful consequence of an upcoming event that is likely to happen ( Folkman & Lazarus, 1985 ). Although anticipatory coping is posited to be situation-specific and associated with reduced response (or reactivity) to a stressor ( Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997 ; Schwarzer & Knoll, 2003 ), we are unaware of any research that has examined anticipatory coping from a within-person perspective within changing contexts (i.e., various stressor domains). Anticipatory coping can reduce reactivity to stressors by facilitating the management of known risks and capitalizing on initial coping efforts ( Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997 ; Schwarzer & Knoll, 2003 ). Although not all stressful events can be foreseen, it is predicted that anticipatory coping efforts can maintain or improve health by reducing the impact of stressors. For example, contextual anticipatory behaviors (e.g., coming up with a plan when an interpersonal conflict is foreseen) may reduce the negative effect of a stressor that is likely to occur ( Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997 ).

Feldman and Hayes (2005) defined four forms of contextual anticipatory behaviors designed to cope with a predicted upcoming stressor in their Measure of Mental Anticipatory Processes (MMAP). Problem Analysis is active contemplation of the causes and meaning of a future stressor. Plan rehearsal involves envisioning the steps required to solve the anticipated stressor. Stagnant deliberation is effortful cognition that dwells repetitively on a stressful situation, but does not find any solutions to the problem. Outcome fantasy involves responding to problems by daydreaming or fantasizing desired outcomes. Feldman and Hayes considered stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy as most likely maladaptive regardless of the particular stressor context, but their assessment of anticipatory coping was from a between-person perspective. They noted that anticipatory coping is likely to vary over time and across situations and domains, and called for future researchers to use their items in a longitudinal study with ongoing naturalistic stressors. We answer this call in the current study by using their items in a naturalistic daily diary design where we take a dynamic, within-person perspective that assumes anticipatory coping changes over time and within stressor contexts. Importantly, our contextually based approach allows for the possibility that any of the four coping forms could be detrimental or beneficial in a given situation.

Present Study

The present study used daily diary methods to address questions of anticipatory coping and daily outcomes. Questions were not framed from a between-person perspective (e.g., adaptive copers vs maladaptive copers); rather, coping was examined as a dynamic within-person process that can change across days and within stressor domains. Although the field has acknowledged that coping is contextual ( Aldwin, 2007 ) and dynamic ( Lazarus, 1999 ), questions remain framed in between-person terms (e.g., some people cope better with arguments than others; cf. Roesch et al., 2010 ). The perspective of the current study acknowledges that coping behaviors can change from day to day as well as within stressor contexts. This is a shift toward a truly dynamic coping model, which Lazarus (1999) called for when he described the requirement of an intraindividual research design in which the same individuals are studied in different contexts and at different times. Our contextual and dynamic perspective also permits the examination of pathways to daily health and well-being benefits as they unfold over time within aging individuals’ daily lives.

Our first aim reflects the dynamic nature of anticipatory coping: we expected significant within-person fluctuations in anticipatory coping, in line with previous research on the importance of context when coping with stressors that have already occurred ( Aldwin, 2007 ) as well as the flexibility in older adults’ coping strategies ( Staudinger & Fleeson, 1996 ). Within this aim we also examined whether anticipatory coping would vary by age within our older adult sample. Given recent longitudinal findings of stability in several forms of coping in older age ( Diehl et al., 2014 ), it seemed reasonable to expect minimal age differences in coping within our older adult sample. Our second aim examined the main effect of anticipatory coping upon well-being within the context of coping with potential daily arguments. Based on previous between-person investigations ( Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ), we could expect that forms of anticipatory coping typically considered maladaptive (i.e., stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy) would be related to worse well-being and those typically considered adaptive (i.e., plan rehearsal and problem analysis) would be related to better well-being. We focused on stressors involving arguments for the second aim because interpersonal stressors tend to be the most frequently reported daily stressors ( Almeida & Horn, 2004 ) and they are also linked with the outcomes in the present study: affect, physical symptoms ( Neupert et al., 2007 ), and memory failures (e.g., Neupert et al., 2006a ; Neupert, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2008 ). Assessing outcomes in multiple domains is necessary as the effects of anticipatory coping may differ by domain. Our third aim examined whether reactivity to arguments (operationalized as the within-person slope between arguments and an outcome, following previous convention [ Almeida, 2005 ; Neupert et al., 2006a , 2007 ]) would depend on daily anticipatory coping.

Method

Participants

Participants were from the Anticipatory Coping Every Day (ACED) study and were recruited through presentations at community activity groups targeted for older adults in central North Carolina. Potential participants were informed about the purpose of the study and were screened for cognitive impairment with the Short Blessed test ( Katzman et al., 1983 ). Individuals who scored ≤8 were included in the study.

Participants read and signed informed consent forms and provided contact information for mailing of compensation. They were then given the packets of daily diary questionnaires, along with prepaid envelopes to return to the primary investigator. Of 51 initial participants, 43 returned diary packets. Participants were aged 60–96 ( M = 74.65, SD = 8.19), and included 39 women (90.7%) and 4 men (9.3%). Twenty-two (51.2%) were African American, 20 (46.5%) were White, and 1 (2.9%) was Asian.

Participants completed diaries over nine consecutive days at home. The first packet collected baseline and demographic information (e.g., personality and SES). The following packets—to be opened on each of the 8 days—contained items assessing daily stressors, anticipatory coping, memory failures, affect, and physical health symptoms. Participants mailed back completed packets and were subsequently debriefed over the phone. A $20 gift card was sent via mail for completing five or more study days, and a $10 card for four or fewer days. The compliance rate was 98.2%, with 380 out of a possible 387 days completed. It is important to note that the aims for the present study rely on day-level information, so power was primarily derived from the number of days ( n = 380; Snijders, 2005 ). Post hoc estimates of power ( Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007 ) indicated that we had a power level of .82 when assuming a small effect size (.15).

Measures

Daily measures

Daily stressors The paper and pencil version ( Neupert, Almeida, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2006b ) of the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE: Almeida et al., 2002 ) was used to assess daily stressors and consisted of stem questions asking whether daily stressors across seven domains had occurred within the past 24hr. Domains included arguments, avoided arguments, work/volunteer-related stressors, home-related stressors, network-related stressors (an event that happened to another individual, but had an effect on the participant), health-related stressors, or other (stressors that may not have fit into the other categories; not analyzed in the current study) domains. Participants received a score of 0 when no stressor was reported, and 1 when a stressor was reported.

Daily anticipatory coping was measured using the MMAP originally developed by Feldman and Hayes (2005) , which assesses productive and unproductive patterns of mental preparation in coping with future stressful events. The original questionnaire was modified to be asked on a daily basis.

The items for the daily MMAP were taken from the final factor analysis by Feldman and Hayes (2005) . The daily questionnaire consisted of 15 items. Each day, the same set of 15 questions was asked 7 times in the same order: one set for each domain of anticipated stressor expected to happen the following day (argument, avoided argument, work, home, network, health, and other domain, matching the domains of the DISE questionnaire). For each stressor domain, participants were asked to report on the likelihood of the given stressor occurring within the next 24hr (e.g., How likely is it that you will have an argument or disagreement with someone within the next 24 hr?). This question was answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ( not at all likely ) to 5 ( extremely likely ). Higher scores indicated a greater expected likelihood of a stressor the following day.

Within each stressor domain, participants reported the frequency of daily anticipatory coping, regardless of whether the stressor was likely to occur. The initial probe, “When you think about this (potential argument or disagreement) how often do you:”, was followed by a list of 15 items representing the four factors of anticipatory coping. Problem analysis contained five items (e.g., “I think about why the problem is happening”). Plan rehearsal contained three items (e.g., “I think about the solution in a step-by-step fashion”). Stagnant deliberation contained five items (e.g., “I think about the problem without making progress on it”). Outcome fantasy contained two items (e.g., “I daydream about the problem fixing itself”). Each item was answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ( never ) to 5 ( always ). Daily mean composite scores were created for each of the four factors for each stressor with higher scores indicating a greater amount of anticipatory coping behaviors performed.

Daily memory failures were assessed daily through a shortened version of a questionnaire developed by Sunderland, Harris, and Baddeley (1983) . The original consisted of 35 yes/no questions tapping five distinct aspects of everyday memory failures: “speech,” “reading and writing,” “faces and places,” “actions,” and “learning new things.” To reduce participant burden, we selected one item from each of the five aspects, specifically choosing the ones that were most likely to be endorsed (see Neupert et al., 2006b for validation of the scale as well as the items). The diary also included an item assessing everyday memory failures regarding medication adherence. The memory failure composite was calculated for each day based on the sum of the six memory failure items, with higher scores representing more memory failures.

Daily affect was measured using The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS: Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988 ). The PANAS consists of two 10-item mood scales each containing words describing different feelings and emotions ( Watson et al., 1988 ). Participants indicated to what extent they experienced each emotion during each of the eight consecutive days. Responses ranged from 1 ( slightly or not at all ) to 5 ( extremely ). A mean composite for daily negative affect was calculated for each day, with higher scores indicating more negative affect.

The measure of daily physical symptoms was based on a modified version of Larsen and Kasimatis’s (1991) physical symptom checklist and consisted of 26 different symptoms (e.g., headaches, backaches, sore throat, and poor appetite). Participants responded yes or no to the list of symptoms. A daily composite was created for each day based on the sum of experienced symptoms. Higher scores indicate more reported physical symptoms, or poorer physical health.

Covariates

Neuroticism was included as a covariate because it is a risk factor for poor health ( Aldwin, Spiro, & Park, 2006 ). Neuroticism was assessed with the neuroticism subscale of the NEO-FFI ( Costa & McCrae, 1992 ). Participants rated 12 items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 ( strongly agree ) to 5 ( strongly disagree ). A mean composite was calculated for each person.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was included as a covariate because resource accumulation is a key component of one’s ability to cope with stressors before they occur ( Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997 ). SES was operationalized as the highest year of school completed.

Participants’ number of life event stressors was included as a covariate to attempt to separate stressor history from the dynamic process of coping with daily stressors. Life event stressors were measured by the Elders Life Stress Inventory (ELSI: Aldwin, 1991b ). Participants responded yes or no to a list of 31 different stressors that could have occurred over the past 12 months. The sum of affirmative responses was used as a composite for each person.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study variables, separated by stressor domain, are presented in Table 1 . Interpersonal tensions (arguments or potential arguments) were the most frequently reported stressors and occurred on 16% of the study days. Stressors in other domains were reported as follows: network stressors (15%), home stressors (13%), health stressors (8%), and work/volunteer-related stressors (7%). Although interpersonal tensions only occurred on a small percentage of the study days, it is important to note that 51% of the participants reported one or more interpersonal tensions across the eight study days, and participants reported on their anticipatory coping the day before the stressors in question. Thus, anticipatory coping, arguments (yes/no), and the outcome variables were reported on all study days. Between-person correlations among individual differences in age, education, neuroticism, and stressful life events with the daily anticipatory coping scales are presented in Supplementary Table 1 . Consistent with our expectations in Aim 1, there were minimal age differences in anticipatory coping; age was only negatively associated with problem analysis for arguments ( r = −.34, p = .04) and plan rehearsal for potential arguments ( r = −.32, p = .048), and home stressors ( r = −.34, p = .04; Analyses examining potential age differences in coping were also examined through a series of multilevel models. Results from these models were consistent with the bivariate correlation results reported here.). Education tended to be positively correlated with problem analysis and plan rehearsal, neuroticism tended to be negatively correlated with problem analysis and plan rehearsal, and stressful life events tended to be negatively correlated with plan rehearsal.

Means and Standard Deviations of all Study Variables by Stressor Domain

| . | Argument . | Pot. arg. . | Work . | Home . | Network . | Health . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem analysis | 2.55 (1.16) | 2.51 (1.15) | 1.88 (1.25) | 2.62 (1.12) | 2.61 (1.18) | 2.68 (1.16) |

| Plan rehearsal | 2.62 (1.29) | 2.54 (1.26) | 2.00 (1.38) | 2.73 (1.26) | 2.54 (1.23) | 2.59 (1.29) |

| Stagnant deliberation | 1.72 (0.66) | 1.74 (0.66) | 1.40 (0.60) | 1.70 (0.63) | 1.72 (0.65) | 1.76 (0.72) |

| Outcome fantasy | 1.56 (0.82) | 1.50 (0.83) | 1.22 (0.46) | 1.46 (0.78) | 1.45 (0.76) | 1.53 (0.84) |

| Age | 74.65 (8.10) | |||||

| Education level | 6.74 (2.27) a | |||||

| Neuroticism | 2.19 (0.55) | |||||

| ELSI | 2.44 (2.08) |

| . | Argument . | Pot. arg. . | Work . | Home . | Network . | Health . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem analysis | 2.55 (1.16) | 2.51 (1.15) | 1.88 (1.25) | 2.62 (1.12) | 2.61 (1.18) | 2.68 (1.16) |

| Plan rehearsal | 2.62 (1.29) | 2.54 (1.26) | 2.00 (1.38) | 2.73 (1.26) | 2.54 (1.23) | 2.59 (1.29) |

| Stagnant deliberation | 1.72 (0.66) | 1.74 (0.66) | 1.40 (0.60) | 1.70 (0.63) | 1.72 (0.65) | 1.76 (0.72) |

| Outcome fantasy | 1.56 (0.82) | 1.50 (0.83) | 1.22 (0.46) | 1.46 (0.78) | 1.45 (0.76) | 1.53 (0.84) |

| Age | 74.65 (8.10) | |||||

| Education level | 6.74 (2.27) a | |||||

| Neuroticism | 2.19 (0.55) | |||||

| ELSI | 2.44 (2.08) |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory; Pot. arg. = potential argument.

a Corresponds to approximately 3 years of college.

Means and Standard Deviations of all Study Variables by Stressor Domain

| . | Argument . | Pot. arg. . | Work . | Home . | Network . | Health . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem analysis | 2.55 (1.16) | 2.51 (1.15) | 1.88 (1.25) | 2.62 (1.12) | 2.61 (1.18) | 2.68 (1.16) |

| Plan rehearsal | 2.62 (1.29) | 2.54 (1.26) | 2.00 (1.38) | 2.73 (1.26) | 2.54 (1.23) | 2.59 (1.29) |

| Stagnant deliberation | 1.72 (0.66) | 1.74 (0.66) | 1.40 (0.60) | 1.70 (0.63) | 1.72 (0.65) | 1.76 (0.72) |

| Outcome fantasy | 1.56 (0.82) | 1.50 (0.83) | 1.22 (0.46) | 1.46 (0.78) | 1.45 (0.76) | 1.53 (0.84) |

| Age | 74.65 (8.10) | |||||

| Education level | 6.74 (2.27) a | |||||

| Neuroticism | 2.19 (0.55) | |||||

| ELSI | 2.44 (2.08) |

| . | Argument . | Pot. arg. . | Work . | Home . | Network . | Health . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem analysis | 2.55 (1.16) | 2.51 (1.15) | 1.88 (1.25) | 2.62 (1.12) | 2.61 (1.18) | 2.68 (1.16) |

| Plan rehearsal | 2.62 (1.29) | 2.54 (1.26) | 2.00 (1.38) | 2.73 (1.26) | 2.54 (1.23) | 2.59 (1.29) |

| Stagnant deliberation | 1.72 (0.66) | 1.74 (0.66) | 1.40 (0.60) | 1.70 (0.63) | 1.72 (0.65) | 1.76 (0.72) |

| Outcome fantasy | 1.56 (0.82) | 1.50 (0.83) | 1.22 (0.46) | 1.46 (0.78) | 1.45 (0.76) | 1.53 (0.84) |

| Age | 74.65 (8.10) | |||||

| Education level | 6.74 (2.27) a | |||||

| Neuroticism | 2.19 (0.55) | |||||

| ELSI | 2.44 (2.08) |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory; Pot. arg. = potential argument.

a Corresponds to approximately 3 years of college.

Fully unconditional multilevel models ( Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002 ) were used to test the dynamic nature of anticipatory coping expected in Aim 1. These models contained no predictors and yielded estimates of within-person (σ 2 ) and between-person (τ 00 ) variability. The estimates were used to obtain the intraclass correlation coefficient [ρ = τ 00 / (τ 00 + σ 2 )], which represents the amount of between-person variance in the dependent variable. Results from these models are presented in Supplementary Table 2 . Consistent with expectations, there was a significant amount of within-person variance for each measure of daily anticipatory coping in each of the six stressor domains. The amount of within-person variance in each of the measures ranged from 17% to 52%, with a median of 41%.

Aim 2 regarding within-person coupling of daily anticipatory coping for arguments and outcomes was addressed through a series of multilevel models. Separate models were conducted for each outcome (affect, physical symptoms, and memory failures) and measure of daily anticipatory coping (problem analysis, plan rehearsal, stagnant deliberation, and outcome fantasy) because preliminary analyses revealed significant associations among the daily anticipatory coping scales (all p s <.001 from within-person multilevel models). Each model was a lagged model, where the previous day’s outcome (e.g., affect) and coping (e.g., plan rehearsal) were used as predictors of the current day’s outcome (e.g., affect). Daily anticipatory coping differences in reactivity were examined through a Coping × Argument interaction to address Aim 3. All models included age, education, neuroticism, and the number of stressful life events as between-person covariates. Estimates of effect size were calculated based on the equations outlined by Snijders and Bosker (2011 ; We conducted additional models to attempt to distinguish the effect of yesterday’s dependent variable (i.e., negative affect, physical symptoms, and memory failures) from the effects of interest (i.e., anticipatory coping). For each dependent variable, we calculated a model with yesterday’s dependent variable as the only predictor. We then compared the estimate of residual within-person variance from these models to the unconditional model (no predictors included). Results indicated that yesterday’s dependent variable only explained 1% (negative affect, memory failures) or less (physical symptoms) of the within-person variance. This is not necessarily unexpected, as the relationship between yesterday’s dependent variables and today’s dependent variables represents a stability effect that is likely attributed to between-person (Level 2) characteristics. Given that our predictors of interest are at Level 1, we are confident that the estimates of effect size at Level 1 within Tables 2–4 accurately represent the magnitude of the anticipatory coping effects.).

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) From Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Negative Affect, Controlling for Previous Day’s Negative Affect

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | 1.06** (.34) | 1.02* (.39) | 0.90* (.38) | 1.07** (.31) |

| Age, γ 01 | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.04 (.05) | −0.00 (.06) | 0.00 (.06) | −0.05 (.05) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s negative affect, γ 10 | 0.06 (.08) | 0.05 (.07) | 0.10 (.07) | 0.11 (.07) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.09** (.03) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.02 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.03 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.08** (.02) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 0.25 (.24) | −0.28 (.42) | 0.19 (.32) | 0.38* (.16) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.05 (.11) | 0.25 (.17) | 0.05 (.11) | −0.02 (.05) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Negative affect (τ 00 ) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.02* (.01) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) |

| R2 between-person | 24% | 1% | 13% | 27% |

| R2 within-person | 6% | 0% | 0% | 11% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | 1.06** (.34) | 1.02* (.39) | 0.90* (.38) | 1.07** (.31) |

| Age, γ 01 | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.04 (.05) | −0.00 (.06) | 0.00 (.06) | −0.05 (.05) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s negative affect, γ 10 | 0.06 (.08) | 0.05 (.07) | 0.10 (.07) | 0.11 (.07) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.09** (.03) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.02 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.03 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.08** (.02) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 0.25 (.24) | −0.28 (.42) | 0.19 (.32) | 0.38* (.16) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.05 (.11) | 0.25 (.17) | 0.05 (.11) | −0.02 (.05) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Negative affect (τ 00 ) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.02* (.01) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) |

| R2 between-person | 24% | 1% | 13% | 27% |

| R2 within-person | 6% | 0% | 0% | 11% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) From Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Negative Affect, Controlling for Previous Day’s Negative Affect

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | 1.06** (.34) | 1.02* (.39) | 0.90* (.38) | 1.07** (.31) |

| Age, γ 01 | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.04 (.05) | −0.00 (.06) | 0.00 (.06) | −0.05 (.05) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s negative affect, γ 10 | 0.06 (.08) | 0.05 (.07) | 0.10 (.07) | 0.11 (.07) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.09** (.03) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.02 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.03 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.08** (.02) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 0.25 (.24) | −0.28 (.42) | 0.19 (.32) | 0.38* (.16) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.05 (.11) | 0.25 (.17) | 0.05 (.11) | −0.02 (.05) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Negative affect (τ 00 ) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.02* (.01) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) |

| R2 between-person | 24% | 1% | 13% | 27% |

| R2 within-person | 6% | 0% | 0% | 11% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | 1.06** (.34) | 1.02* (.39) | 0.90* (.38) | 1.07** (.31) |

| Age, γ 01 | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) | −0.00 (.00) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.04 (.05) | −0.00 (.06) | 0.00 (.06) | −0.05 (.05) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.02 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.01 (.02) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s negative affect, γ 10 | 0.06 (.08) | 0.05 (.07) | 0.10 (.07) | 0.11 (.07) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.09** (.03) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.02 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.03 (.02) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.08** (.02) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 0.25 (.24) | −0.28 (.42) | 0.19 (.32) | 0.38* (.16) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.05 (.11) | 0.25 (.17) | 0.05 (.11) | −0.02 (.05) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Negative affect (τ 00 ) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.03* (.01) | 0.02* (.01) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) |

| R2 between-person | 24% | 1% | 13% | 27% |

| R2 within-person | 6% | 0% | 0% | 11% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) From Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Physical Symptoms, Controlling for Previous Day’s Physical Symptoms

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.31 (1.01) | −0.32 (1.32) | −0.61 (1.29) | −0.03 (.95) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.00 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.00 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.03 (.17) | 0.12 (.21) | 0.14 (.21) | −0.03 (.16) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.04) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.04) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.05 (.05) | 0.03 (.06) | 0.03 (.05) | 0.04 (.04) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s physical symptoms, γ 10 | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.54*** (.06) | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.59*** (.05) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.30* (.12) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.07 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.10 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.22* (.09) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | −0.49 (.93) | −0.15 (1.71) | −1.79 (1.36) | −0.77 (.66) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.19 (.40) | −0.00 (.68) | 0.55 (.45) | 0.22 (.22) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Physical symptoms (τ 00 ) | 0.11 (.15) | 0.25 (.19) | 0.22 (.18) | 0.08 (.14) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 1.01*** (.14) | 0.98*** (.13) | 0.97*** (.13) | 1.01*** (.14) |

| R2 between-person | 91% | 73% | 74% | 85% |

| R2 within-person | 46% | 43% | 44% | 50% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.31 (1.01) | −0.32 (1.32) | −0.61 (1.29) | −0.03 (.95) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.00 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.00 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.03 (.17) | 0.12 (.21) | 0.14 (.21) | −0.03 (.16) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.04) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.04) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.05 (.05) | 0.03 (.06) | 0.03 (.05) | 0.04 (.04) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s physical symptoms, γ 10 | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.54*** (.06) | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.59*** (.05) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.30* (.12) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.07 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.10 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.22* (.09) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | −0.49 (.93) | −0.15 (1.71) | −1.79 (1.36) | −0.77 (.66) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.19 (.40) | −0.00 (.68) | 0.55 (.45) | 0.22 (.22) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Physical symptoms (τ 00 ) | 0.11 (.15) | 0.25 (.19) | 0.22 (.18) | 0.08 (.14) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 1.01*** (.14) | 0.98*** (.13) | 0.97*** (.13) | 1.01*** (.14) |

| R2 between-person | 91% | 73% | 74% | 85% |

| R2 within-person | 46% | 43% | 44% | 50% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) From Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Physical Symptoms, Controlling for Previous Day’s Physical Symptoms

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.31 (1.01) | −0.32 (1.32) | −0.61 (1.29) | −0.03 (.95) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.00 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.00 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.03 (.17) | 0.12 (.21) | 0.14 (.21) | −0.03 (.16) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.04) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.04) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.05 (.05) | 0.03 (.06) | 0.03 (.05) | 0.04 (.04) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s physical symptoms, γ 10 | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.54*** (.06) | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.59*** (.05) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.30* (.12) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.07 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.10 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.22* (.09) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | −0.49 (.93) | −0.15 (1.71) | −1.79 (1.36) | −0.77 (.66) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.19 (.40) | −0.00 (.68) | 0.55 (.45) | 0.22 (.22) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Physical symptoms (τ 00 ) | 0.11 (.15) | 0.25 (.19) | 0.22 (.18) | 0.08 (.14) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 1.01*** (.14) | 0.98*** (.13) | 0.97*** (.13) | 1.01*** (.14) |

| R2 between-person | 91% | 73% | 74% | 85% |

| R2 within-person | 46% | 43% | 44% | 50% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.31 (1.01) | −0.32 (1.32) | −0.61 (1.29) | −0.03 (.95) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.00 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.00 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.03 (.17) | 0.12 (.21) | 0.14 (.21) | −0.03 (.16) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.04) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.04) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.05 (.05) | 0.03 (.06) | 0.03 (.05) | 0.04 (.04) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s physical symptoms, γ 10 | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.54*** (.06) | 0.56*** (.06) | 0.59*** (.05) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.30* (.12) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.07 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.10 (.09) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.22* (.09) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | −0.49 (.93) | −0.15 (1.71) | −1.79 (1.36) | −0.77 (.66) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | 0.19 (.40) | −0.00 (.68) | 0.55 (.45) | 0.22 (.22) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Physical symptoms (τ 00 ) | 0.11 (.15) | 0.25 (.19) | 0.22 (.18) | 0.08 (.14) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 1.01*** (.14) | 0.98*** (.13) | 0.97*** (.13) | 1.01*** (.14) |

| R2 between-person | 91% | 73% | 74% | 85% |

| R2 within-person | 46% | 43% | 44% | 50% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) from Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Memory Failures, Controlling for Previous Day’s Memory Failures

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory failures, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.48 (1.06) | −0.76 (1.25) | −0.68 (1.29) | −0.46 (1.08) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.18 (.18) | −0.14 (.20) | −0.15 (.21) | −0.18 (.18) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s memory failures, γ 10 | 0.38*** (.08) | 0.31*** (.08) | 0.29*** (.08) | 0.37*** (.08) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.00 (.10) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.05 (.07) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.02 (.08) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.03 (.07) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 1.61* (.71) | −0.27 (1.23) | −0.87 (0.98) | 0.90 (.51) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | −0.60* (.30) | 0.23 (.49) | 0.39 (.32) | −0.22 (.16) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Memory failures (τ 00 ) | 0.24 (.16) | 0.31* (.17) | 0.34* (.17) | 0.25 (.16) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.51*** (.07) | 0.50*** (.07) | 0.49*** (.07) | 0.51*** (.07) |

| R2 between-person | 60% | 50% | 47% | 58% |

| R2 within-person | 37% | 31% | 30% | 35% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory failures, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.48 (1.06) | −0.76 (1.25) | −0.68 (1.29) | −0.46 (1.08) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.18 (.18) | −0.14 (.20) | −0.15 (.21) | −0.18 (.18) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s memory failures, γ 10 | 0.38*** (.08) | 0.31*** (.08) | 0.29*** (.08) | 0.37*** (.08) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.00 (.10) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.05 (.07) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.02 (.08) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.03 (.07) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 1.61* (.71) | −0.27 (1.23) | −0.87 (0.98) | 0.90 (.51) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | −0.60* (.30) | 0.23 (.49) | 0.39 (.32) | −0.22 (.16) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Memory failures (τ 00 ) | 0.24 (.16) | 0.31* (.17) | 0.34* (.17) | 0.25 (.16) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.51*** (.07) | 0.50*** (.07) | 0.49*** (.07) | 0.51*** (.07) |

| R2 between-person | 60% | 50% | 47% | 58% |

| R2 within-person | 37% | 31% | 30% | 35% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Unstandardized Estimates (Standard Error) from Multilevel Models of Within-Person Coupling of Daily Anticipatory Coping for Arguments and Memory Failures, Controlling for Previous Day’s Memory Failures

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory failures, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.48 (1.06) | −0.76 (1.25) | −0.68 (1.29) | −0.46 (1.08) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.18 (.18) | −0.14 (.20) | −0.15 (.21) | −0.18 (.18) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s memory failures, γ 10 | 0.38*** (.08) | 0.31*** (.08) | 0.29*** (.08) | 0.37*** (.08) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.00 (.10) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.05 (.07) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.02 (.08) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.03 (.07) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 1.61* (.71) | −0.27 (1.23) | −0.87 (0.98) | 0.90 (.51) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | −0.60* (.30) | 0.23 (.49) | 0.39 (.32) | −0.22 (.16) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Memory failures (τ 00 ) | 0.24 (.16) | 0.31* (.17) | 0.34* (.17) | 0.25 (.16) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.51*** (.07) | 0.50*** (.07) | 0.49*** (.07) | 0.51*** (.07) |

| R2 between-person | 60% | 50% | 47% | 58% |

| R2 within-person | 37% | 31% | 30% | 35% |

| Fixed effects . | Stagnant deliberation . | Plan rehearsal . | Problem analysis . | Outcome fantasy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory failures, β 0 | ||||

| Intercept, γ 00 | −0.48 (1.06) | −0.76 (1.25) | −0.68 (1.29) | −0.46 (1.08) |

| Age, γ 01 | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) | 0.02 (.01) |

| Neuroticism, γ 02 | −0.18 (.18) | −0.14 (.20) | −0.15 (.21) | −0.18 (.18) |

| Education, γ 03 | 0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | −0.01 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| ELSI, γ 04 | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | 0.01 (.05) |

| Slope, β 1 | ||||

| Previous day’s memory failures, γ 10 | 0.38*** (.08) | 0.31*** (.08) | 0.29*** (.08) | 0.37*** (.08) |

| Slope, β 2 | ||||

| Previous day’s stagnant deliberation, γ 20 | 0.00 (.10) | |||

| Previous day’s plan rehearsal, γ 20 | 0.05 (.07) | |||

| Previous day’s problem analysis, γ 20 | 0.02 (.08) | |||

| Previous day’s outcome fantasy, γ 20 | 0.03 (.07) | |||

| Slope, β 3 | ||||

| Argument, γ 30 | 1.61* (.71) | −0.27 (1.23) | −0.87 (0.98) | 0.90 (.51) |

| Slope, β 4 | ||||

| Coping × Argument, γ 40 | −0.60* (.30) | 0.23 (.49) | 0.39 (.32) | −0.22 (.16) |

| Random effects | ||||

| Memory failures (τ 00 ) | 0.24 (.16) | 0.31* (.17) | 0.34* (.17) | 0.25 (.16) |

| Within-person fluctuation (σ 2 ) | 0.51*** (.07) | 0.50*** (.07) | 0.49*** (.07) | 0.51*** (.07) |

| R2 between-person | 60% | 50% | 47% | 58% |

| R2 within-person | 37% | 31% | 30% | 35% |

Notes: ELSI = Elders Life Stress Inventory.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table 2 contains the results from models with negative affect as the dependent variable. Plan rehearsal (γ 20 ) and problem analysis (γ 20 ) were not associated with subsequent negative affect. Increased stagnant deliberation (γ 20 ) and increased outcome fantasy (γ 20 ) were associated with increased negative affect on the subsequent day. Emotional reactivity to arguments (γ 40 ) did not differ by any of the daily anticipatory coping forms.

Table 3 contains the results from models with physical symptoms as the dependent variable. Consistent with the results for negative affect, plan rehearsal (γ 20 ) and problem analysis (γ 20 ) were not associated with subsequent physical symptoms. However, increased stagnant deliberation (γ 20 ) and outcome fantasy (γ 20 ) were associated with increased physical symptoms the subsequent day. Physical reactivity to arguments (γ 40 ) did not differ by any of the daily anticipatory coping forms.

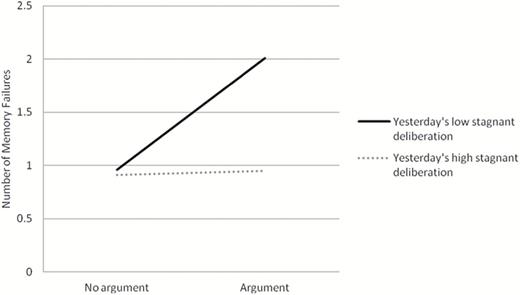

Table 4 contains the results from models with memory failures as the dependent variable. There were no main effects for any of the daily anticipatory coping forms, but cognitive reactivity to arguments did depend on the previous day’s stagnant deliberation (γ 40 ). Separate models (one for days with no arguments and one for days with arguments) were conducted to decompose the interaction. On days with no arguments, previous day’s stagnant deliberation was not related to subsequent memory failures (γ 20 = −0.02, t = −0.23, p = .82). In contrast, on days with arguments, previous day’s stagnant deliberation was associated with a significant decrease in subsequent memory failures (γ 20 = −0.60, t = −3.03, p = .05; Figure 1 ). Stated another way, increased stagnant deliberation was associated with reduced cognitive reactivity to arguments.

Previous day’s stagnant deliberation × arguments for daily memory failures. Low and high stagnant deliberation were operationalized as one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively. Increased stagnant deliberation was associated with reduced cognitive reactivity to arguments.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine the potential effects of dynamic anticipatory coping for older adults. These results extend previous research that has focused on coping after a stressor occurred (e.g., Folkman & Lazarus, 1988 ; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ) or has considered anticipatory coping to be a stable, individual difference construct ( Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997 ; Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ).

Aim 1

Our results from the fully unconditional models for each of the four forms of anticipatory coping within the six stressor domains ( Supplementary Table 2 ) suggest that anticipatory coping is a dynamic within-person process that can change across days and within each stressor domain. Although the field has acknowledged that coping is contextual ( Aldwin, 2007 ), questions are still framed in between-person terms (e.g., some people cope better with arguments than others; cf. Roesch et al., 2010 ). The findings of the current study suggest that coping behaviors can change from day to day within different stressor contexts. Perhaps this reflects individuals’ attempts to match coping behavior with the anticipated stressor, but this should be explicitly examined in future work. Our results are in line with those of Whitehead and Bergeman (2014) who found day-to-day variability in appraisal of events. Because stressors and their anticipation change daily, coping should also change daily. Indeed, this was reflected in the significant within-person variance for all anticipatory coping scales for all stressors. These results represent the first step in building a truly dynamic coping model where anticipatory coping is seen to change with contexts as well as time. Our results also suggest that there are minimal (3 out of 24 correlations were significant) age differences within older adults in daily anticipatory coping. Our findings are congruent with McCrae (1989) and Whitty (2003) who found no age differences in coping when examining between-person differences.

Aim 2

The results from the within-person coupling models examining main effects within the context of coping with potential arguments suggest that stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy can be detrimental for older adults’ affect and physical health. The context of coping with potential arguments was important to examine because interpersonal stressors are the most frequently reported daily stressor in adulthood ( Almeida & Horn, 2004 ) and they are associated with daily physical health ( Almeida et al., 2002 ), affect ( Neupert et al., 2007 ), and memory failures ( Neupert et al., 2006a ). Stagnant deliberation may be detrimental for affect within the context of coping with potential arguments because it involves dwelling repetitively on a stressful problem and experiencing unproductive thoughts ( Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ). When encountering a stressful problem, the discrepancy between current and desired states of being can give rise to repetitive thoughts about the problem ( Martin & Tesser, 1996 ). Perseverative thought has been associated with prolonged symptoms of depression and anxiety ( Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000 ). Outcome fantasy is the tendency to respond to potential problems by daydreaming or fantasizing about desired outcomes while ignoring details of the problem-solving process ( Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ). Engaging in positive daydreams while not expecting to accomplish goals results in negative mood ( Langens & Schmalt, 2002 ). We assume that a similar process may have occurred in the older adults in our sample.

Previous day’s plan rehearsal and problem analysis were not significantly related to well-being. Previous research across various domains suggests that coping at a given point in time can be linked to health and well-being months ( Guardino & Schetter, 2014 ) or even years later ( Ogle, Rubin, & Siegler, 2013 ). It is possible that plan rehearsal and problem analysis are more powerful prior to the day before the likely stressor. Future research examining lags of two or more days may better elucidate the relationship of these two coping forms with well-being.

We are unaware of any research focusing on the link between anticipatory coping and physical health, but we know that the effects of stress and age are interactive: psychological stress can both mimic and exacerbate the effects of aging, with older adults often showing greater immunological impairment to stress than younger adults ( Graham et al., 2006 ). Our results suggest that stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy were detrimental for older adults’ daily physical health and affect within the context of coping with potential arguments. Feldman and Hayes (2005) reported between-person relationships among stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy with psychological well-being, depression, and anxiety: both forms of anticipatory coping were associated with lower levels of well-being and higher levels of depression and anxiety. We extend their findings to the context of potential arguments and also demonstrate the dynamic nature of these relationships by applying lagged models to daily diary data.

Based on these findings, one might assume that stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy are never adaptive for coping with potential arguments; however, it is important to remember that our within-person, contextually based approach allowed us to examine the circumstances when each of the four coping forms could be detrimental or beneficial.

Aim 3

Contrary to what would be expected based on previous between-person findings ( Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ), some within-person effects of stagnant deliberation may be beneficial for older adults’ cognitive reactivity to arguments. Given the number of models conducted however, the result of this interaction should be interpreted with caution and considered preliminary, pending replication, even though the effect sizes (37% within-person and 60% between-person) suggest that the model is a good fit to the data. Previous research with the stagnant deliberation items and the relationship between arguments and memory failures may shed light on this interaction. Stagnant deliberation has been positively associated with an active cognitive style ( Feldman & Hayes, 2005 ), which Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, and Heimberg (2002) suggested may help individuals to make sense of and cope with their experiences more effectively. It is possible that the specific items for stagnant deliberation (e.g., Even though I really concentrate on it, I don’t seem to get any answers; I think about how to solve the problem, but the thoughts just spin around in my head) represent the cognitive benefits of deliberating on a possible solution, even if the participant appraises that the deliberation is not helpful at the time. This is especially important when one considers that anticipatory coping was captured in real time; that is, anticipatory coping was reported on one day, and the argument in question did not occur until the following day (if it happened at all). Although speculative, it is possible that the participant did not think the deliberation was helpful at the time, but in fact the deliberation could have been helpful if the argument happened the following day.

The relationship between arguments and memory failures for older adults is also an important consideration. We know from our previous work ( Neupert et al., 2006a ) that days with arguments are associated with increases in memory failures for older adults. Arguments may be distracting for older adults, who tend to be solution-oriented when faced with an interpersonal conflict ( Bergstrom & Nussbaum, 1996 ) and therefore place more effort and attention into finding a solution. Interpersonal stressors have been linked to intrusive cognitions ( Sarason, Pierce, & Sarason, 1996 ), which could potentially produce memory failures through cognitive interference. Feldman and Hayes (2005) found that stagnant deliberation was associated with three measures of avoidance. It is possible that stagnant deliberation results in a type of disengagement that prevents arguments from being distracting, thus preventing memory failures.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of the current study should be considered within the context of several limitations. The small percentage of men in the sample limits the generalizability of the findings. Although Feldman and Hayes (2005) did not find any gender differences in the between-person relationships between their MMAP and well-being outcomes, future studies could examine whether this pattern is also true for contextual and dynamic processes. Additionally, we standardized the presentation of the MMAP items, so future studies with the items counterbalanced could test whether the order matters. The current sample focused on older adults; future research could include participants from the adult lifespan so that age-related differences in these processes can be examined. Although the current measure of physical symptoms has been successfully used in previous daily diary studies (e.g., Almeida et al., 2002 ; Neupert et al., 2007 ), future research with objective measures of health (e.g., cortisol) may uncover physical reactivity effects that were not found here. We focused on reactivity to arguments to keep the scope of the current study reasonable, but future studies could include reactivity to stressors in other domains (e.g., home), to further examine the notion of the importance of matching between coping and context ( Aldwin, 2007 ). We chose to conduct separate models for each form of coping based on analyses to determine the percentage of overlap at the within-person level among the four forms of coping within the context of arguments. Results ranged from 7% (plan rehearsal associated with outcome fantasy) to 48% (problem analysis associated with stagnant deliberation), with most of the results yielding estimates closer to the lower end. Because of the statistically significant relationships among each of the measures of coping as well as the range in overlap (suggesting that it would be difficult to clearly combine subscales) we believe this warranted analyzing the forms separately. However, future work should continue to examine the within-person relationships among the measures and see if there could be clear ways to create meaningful composites. Lastly, our decision to focus on a lag of one day (yesterday predicting today) revealed interesting coupling patterns with stagnant deliberation and outcome fantasy, but no effects were found for problem analysis or plan rehearsal. Future research that examines lags of two or more days would be able to examine the possible distinction in the cadence of anticipatory coping.

Conclusion

Limitations notwithstanding, this is the first investigation of anticipatory coping and stressors within the framework of a daily diary design. Our results suggest that daily anticipatory coping is dynamic; people are not using the same coping tool in all circumstances or at all times. Daily anticipatory coping is also linked to outcomes within the context of arguments, but the directions of the effects differ, once again highlighting the contextual and dynamic process. In this sample of older adults, a coping form previously considered maladaptive (stagnant deliberation) may be adaptive for cognitive reactivity within the context of preparing for tomorrow’s potential argument. There is likely a time and a place for all forms of coping, and we encourage further examination of its dynamic and contextual nature.

Funding

This work was supported by a faculty research and professional development grant awarded to Shevaun D. Neupert from North Carolina State University.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Bob G. Knight, PhD